« Features

Art Criticism and Metamodernism

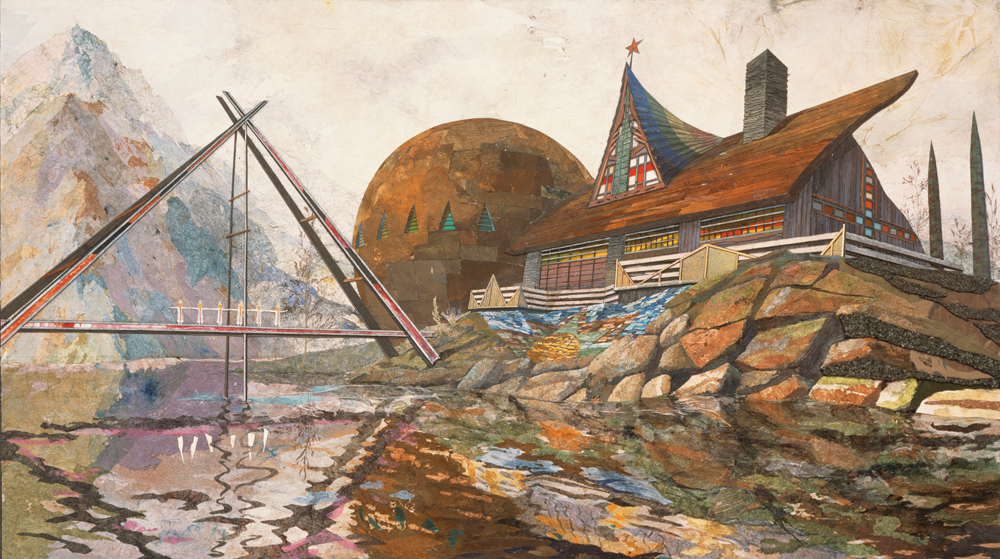

Rob Voerman, Tarnung #3, 2009, glass, Plexi-glass, wood, cardboard, a.o.m., Courtesy of Upstream Gallery. Installation view of “Modernisn as a Ruin,” at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein.

By Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker

These are odd times. After a decade of relative peace and wealth, at least from a Western perspective, the world is in all kinds of disarray. In 2008, the global debt crisis put an end to the myth of the middle classes, exposing the monumental gap (previously papered over by debt) between the one percent and the rest of us. Meanwhile, political stability was fractured by oil crises and Wikileaks, the Occupy movement and the rise of populist extremism. There have been uprisings and demonstrations, hacked email accounts and successful Twitter petitions.

The arts have changed as well, perhaps as a consequence, perhaps coincidentally. But changed they have. Substantially. In stark contrast with the art of the 1990s, which tended to be characterized by irony, cynicism and deconstruction, contemporary practices are often discussed in terms of affection, sincerity and hopefulness. Another label that is featured with some frequency is ‘authenticity.’ As the renowned New York art critic Jerry Saltz put it, the “genus of cynical art that is mainly about gamesmanship, work that is coolly ironic, simply cool, ironic about being ironic, or mainly commenting on art that comments on other art” has become less popular. There is a new “attitude that says I know that the art I’m creating may seem silly, even stupid, or that it might have been done before, but that doesn’t mean this isn’t serious.”1

Unsurprisingly, given these social and aesthetic shifts, scholars and critics alike have started to speak of an end to postmodernism. The current paradigm has been variously called altermodernism (curator Nicolas Bourriaud), cosmodernism (literary theorist Christian Moraru), hypermodernism (philosopher Alan Kirby) and automodernism (cultural theorist Robert Samuels). We ourselves, linking the social and aesthetic changes to changes in capitalism, have argued for the use of the term metamodernism to describe the dominant structure of feeling of the early 21st century. But whatever the precise nature of the changes, and regardless of the label we stick to them, it is evident that a new experiential register requires a novel critical vernacular. It would be silly, after all, to draw on the exact same theoretical concerns to discuss the French Revolution and the Indignados, just as it does not make sense to see Rembrandt’s portraits through the same lens as Picasso’s ladies from Avignon. Different registers demand different critical discourses. These discourses may overlap, they may inform each other, they may share this or that concern (globalization, capitalism, false consciousness) or theoretical assumption (Kantian aesthetics, Badiou’s event), but they need to be different and adapted to time, place and biography.

What follows below is our attempt to sketch out-roughly, cautiously-the contours of such a language. In doing so, we generalize and gloss over differences. Conversely, we at times state the perfectly obvious, ideas that others have expressed much more eloquently. But what we hope to achieve, to establish, is a line of flight: a sense of how we may begin to think theoretically beyond the parameters we were taught in history classes in art schools and universities; a modality that allows us to align our concepts with the intuitions so many of us seem to share. For art critics are not just arbiters of quality, they are also interpreters of change-in sentiment, in thinking, in taste. That things have changed, so much is obvious; it’s time we started to make sense of these changes.

HISTORY HASN’T ENDED, NOR HAS ART

After the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, signifying the collapse of the Soviet Union and its accompanying ideological framework, there was widespread consensus that history had come to an end. The ideological struggle was over, philosophers cried out triumphantly; politicians agreed that the battle between nations had finally been decided. As the conservative critic Francis Fukuyama famously put it, with the “unabashed victory of liberal democracy,” mankind had achieved a form of society that satisfied its deepest and most fundamental longings. This did not mean that the natural cycle of birth, life, and death would end, that important events would no longer happen, or that newspapers reporting them would cease to be published. It meant, rather, that there would be no further progress in the development of underlying principles and institutions, because all of the really big questions had been settled.2

Some 25 years later, all this talk seems close to inconceivable. Whether it was 9/11 or the collapse of Lehmann Brothers, the fall of the PIIGS or the rise of the BRICS, the Arab Spring or the stagnation of the European project, Wikileaks or the PRISM affair, it has become abundantly clear that liberal democracy, capitalist progress and 20th-century theory do not mark the end of our evolution. Indeed, as Fukuyama himself grudgingly admitted in 2012, maybe all those proclamations of the end of history had been a bit opportunistic. Perhaps history hadn’t ended, after all. It had merely paused.

Kris Lemsalu, In My Bathtub I ́m The Captain, 2012, ceramics, textile, metal, approx. 40” x 30” x 27.2.” Courtesy of Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin.

All these developments, however, would still amount to nothing but a series of unrelated events which, when seen in isolation, do not amass, to refer to that classic Baudrillardian pun, the energy to reach the escape velocity needed to break out of the post-historical deadlock. If we say that history has entered a new stage, we need to attempt to think about the present historically, to periodize. This requires that we conceptualize these developments together. Unfortunately, we have to save the extended version of our attempt to periodize the present for another book and another time. Yet what we can say here is that a particularly interesting starting point would be the essay on Fukuyama’s End of History written by Fredric Jameson, the theorist who successfully studied together all those developments we now call postmodernism.3 For Jameson, the historical significance of all those discussions about the End of History does not lie in their accuracy, although he admits the thesis encapsulates the euphoria of victory of the ‘neoconservative right’ and the defeatism of the ‘progressive left’ of the time, but is rather to be found in its conditions and implications. The general sense of an ending-i.e., the fact that such an end is conceivable and more or less plausible-stemmed from two mutations in capitalism itself, he argues. First of all, the emergence of a truly globalized world market, from the Second World War onwards, makes an even further expansion and penetration of capitalism impossible. Capital had simply reached its spatial limits. This is to say that “Fukuyama’s end of history is not really about Time at all, but rather about Space.” His second argument pertains to the increasing impossibility to imagine a social moment before or after capitalism. Under the postmodern, there simply is no region left untouched by the process of commodification; even our unconscious has been colonized. “The notion of the ‘end of history’ also expresses a blockage of the historical imagination.”4

This classic Jamesonian analysis, which plays itself out, as it were, on two chessboards simultaneously, the global and the local, raises, then, just as many questions in the context of our current historical moment. Are we not witnessing yet another set of mutations in capitalism? Globally, the postmodern moment of capitalism was very much related to the hegemony, in terms of economic, political and military power, of the United States and other so-called ‘Western’ nations. Yet today’s geopolitical economy doesn’t revolve around a single pole but oscillates among a wide variety of poles. It has become polycentric. The rise of the BRICs is only the most superficial symptom of this multipolar world system. Far more interesting is how various versions of capitalism compete for influence and resources in their overlapping regions, from the Confucian (China) and the Maffia (Russia) to the Islamic (Turkey) and the sectarian (India) and, yes, still, the (neo)liberal democratic. Global capitalism may have reached its spatial limits a while ago; today’s geopolitical playing field, and its rules, have changed significantly.5

On the local level of everyday experience, meanwhile, we witness a rebirth of a historical imagination of precisely the kind Jameson deemed dead and buried under so many layers of capital in the mass mediatized comfort zone at the End of History. The financial crises, which affected everyone from banks and states to homeowners and students, the looming catastrophe of the various ecological crises, and the increasing interconnectedness of our social lives, all contributed in one way or another to our capacity to conceive of capitalism as one of many-instead of the only, let alone best-possible worlds. Besides the current, worldwide wave of protests, the most clear example here is the increasing prevalence of the notion of the commons, which cuts transversally across these themes, as an ideological framework that addresses the historical process of the enclosure of communal resources (i.e. pre-capitalist) and evokes alternative forms of social relations and ownership (i.e. post-capitalist). Today’s “commonists,” a varied bunch of liberal lawyers, Internet theorists, networked citizens, environmental activists and communist thinkers, are, in other words, symptomatic of an age in which we are once more capable to conceive of history and to envision alternative endings.

We suggest that all this requires us to revisit yet another ‘end’-that of art itself. We refer, here, to Arthur Danto’s preposterous claim that the evolution of art has come to a halt after the dissolution of all those boundaries previously honored by art and for the sake of art (say, between art and non-art, high and low, the various disciplines and media, and so on). Contemporary practices, he suggested, would no longer contribute to our understanding of art’s essence, but instead demonstrate that there is no essence, or if there is, that it allows for an eternally expansive variety of forms, methods and concepts. Art is free from all restraints. Today, after all, everything can be art: a Brillo box, a can of soup, a toilet bowl, a turd. But it doesn’t take a visionary to see that artists today are still very much concerned with Bildung, with imagining alternative narratives, communities and systems of rule and exchange. Further, to suggest that pluralism and freedom are one and the same thing carries in it a misunderstanding of freedom. The pluralism of the 1960s and 1970s merely operated under other kinds of restrictions, just as the Romanticism and Classicism Danto discusses, too, functioned under alternative constraints. It is possible that art will diversify even more the next few years, but it is also imaginable that it will become more specific. Whatever its course, we should not simply assume that it has played its part-in terms of affinity, identity, spirituality or otherwise-in our development; it has simply changed its appearance.

David Thorpe, Covenant of the Elect, 2002, mixed media collage, 24 ¾” x 43 ¾.” © the artist. Courtesy of Maureen Paley, London.

INTERTEXTUALITY IS NOT THE SAME AS PASTICHE, EVEN WHEN IT IS ECLECTIC

This suggestion seems so self-evident that it shouldn’t merit explication. But it isn’t; and it does. For many postmodern artists, or at least the particular group of artists that have been theorized by Eagleton, Jameson, Foster et al., intertextuality takes the form of pastiche (rather than, say, of quotation, as the moderns would have it). During much of the 1980s and 1990s, artists eclectically reappropriated stylistic registers and methods from earlier artistic and popular cultural expressions. Some artists, such as Wim Delvoye and Cindy Sherman, did this to critique those registers, or the reality those registers purportedly represented. Others, foremost among them Jeff Koons and Richard Hamilton, arguably, simply rehashed signifiers because they wanted to celebrate their formal aspects, regardless of their original context. But for whatever reason and in whatever manner these artists drew on intertextual references, they emptied or discarded the original. To use the terminology popular in environmental spheres, they ‘downcycled.’

Since the early 2000s, galleries increasingly show art that reappropriates older aesthetic and cultural forms to revisit their substance and redirect their ‘meaning’ elsewhere. Artists like David Thorpe and Rob Voerman, for instance, reuse anything from scrap metal and cardboard to plastic, paper, wood, sand, glass and straw. They also draw on numerous aesthetic and political strategies, such as New Ageism and science fiction, Japanese woodcutting and collage, hippie culture and 19th-century philosophy. This is not yet another form of historicism, though it is that, too; much rather, it is to take the lessons from the past and incorporate them into a present, or future, that is as of yet unattainable. Here, the process has more in common with upcycling.

To illustrate this shift in the strategies used by artists to reflect or comment on both the artistic tradition and social developments, it might be insightful to briefly compare a postmodern work with a typically metamodern one. We have in mind Hamilton’s collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956), credited as one of the highpoints of post-war pop art, and David Thorpe’s collage Covenant of the Elect (2002). Both artists use similar techniques to recycle the scrapheap of history, and even the composition of the works show an uncanny resemblance with those sloping lines on the left side of their frames that cut the somewhat horizontal plateaus supporting their respective worlds. Yet there are plenty of differences.

Hamilton’s collage includes historical references to 19th-century Victorian bourgeois photography (‘framed portrait’) and the era of the silent movies (‘view from window’), which become distant, yet pleasant-on-the-eye spectacles within its individualized consumer space. They are decorative. Floating signifiers. Other references include, of course, the tropes of an emerging consumerist lifestyle, as symbolized by images taken from the popular press. The work’s intertextuality takes, then, the form of a pastiche that serves as an ironic comment on its title’s question and its artist’s historical situation. Thorpe’s collage, too, includes plenty of historical references. He pairs Nietzsche’s tightrope walker with religion (‘Western Christianity, Eastern mysticism’) to fictional worlds (‘Sci-Fi, Westerns’) to self-sufficient communities (‘fascism, communism’) to sectarian fanaticism (‘the elect’). In stylistic terms, the world literally hovers somewhere between Star Trek, New Ageism, the Far West, grand ideologies and the hobos without landing anywhere in particular. It hovers in a zone that is instantly recognizable, as it were, because it reminds one of all these earlier traditions, yet also strange, since its logic adheres to no one specific tradition in particular.

Whereas Hamilton knowingly deconstructs an everyday life devoid of utopian aspirations, Thorpe seeks to reconstruct and reimagine from former utopias and fictional worlds-none of which can be ascertained, some of which have been proven impossible or dangerous-another utopia that is literally nowhere, a no-place. However, the utopia that emerges from Thorpe’s eclectic reappropriation is not unproblematic for the traditions the work appropriates are certainly not compatible. Indeed, science fiction and Romanticism, New Ageism and Christianity, however much they may have in common, however much they may historically be related, they cannot coexist. Each offers its own version of utopia, of transcendence, that is mutually exclusive. Yet somehow he creates an impossible unity, imagines a harmony that cannot be. Thorpe reappropriates conventions and techniques associated with postmodernism, yet redirects and resignifies them towards new horizons. His eclecticism is not, however, simply a matter of ahistorical nostalgia or disaffected futurism. He doesn’t imitate stylistic registers but revisits these older forms in search of their substance, so as to evoke a context that may have been lost on us 21st-century viewers, but may also be worth the while. This practice, then, does not take the form of quotation, parody or pastiche, but something altogether different. Perhaps we could call it upcycling, perhaps ‘reappropriation,’ or allusion, or mention? The term needs to be decided upon still, but it is important that we begin to think beyond the parameters of the postmodern.

Annabel Daou, Which Side Are You On?, 2012, SD video, colour, sound, TV: Grundig Super Color 1631, 1 of two versions, 3:06 min. © the artist. Courtesy of Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin

IRONY AND SINCERITY ARE NOT MUTUALLY EXCLUSIVE

From Saltz to Emily Nussbaum, David Foster Wallace to Zadie Smith, talk of post-irony and the “New Sincerity” has become commonplace among critics. If the modern artists have come to be historicized as an earnest bunch (whether correctly or unfairly is another question), and the postmoderns go into the books as jokers, the current generation of artists attracts descriptions that speak of earnestness and irony in equal measure. But what does it mean to say something is both sincere and ironic? How should we conceive, critically, of a work of art that is as hopeful as it is cynical? German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk has recently theorized the unique taste of the oxymoronic “sweet and sour sauce.” Would that be a starting point? Another resolve would be to study Wittgenstein’s treaty of the ‘duck-rabbit,’ a picture that depicts an ambiguous animal that is either a duck or a rabbit. Perhaps we should revise the annals of German Romanticism, the writings of Schlegel and Schiller and Novalis. For here, too, the emphasis lies with the oscillation between opposing values. It is true that each work of art necessitates its own unique discursive approach, but just as the earnestness of Modernism and the irony of postmodern art revived and gave birth to particular theorems by which to frame, or with which to support, those approaches, so, too, the metamodern metaxis requires a new (knowledge of) theories and a new critical vernacular.

AFFECT HASN’T WANED

Jameson may have been right to suggest that in the context of postmodern culture and aesthetics affect had waned. But contemporary artists have returned humanist values such as empathy and mercifulness to the forefront of their practices, including Peter Doig, Olafur Eliasson, Mona Hatoum, Yael Bartana, Annabel Daou, Kris Lemsalu, Charles Avery, Cyprien Gaillard, Ragnar Kjartansson, Guido van der Werve, Sejla Kameric and Mariechen Danz.

THE INTERNET IS A GAME CHANGER

Of course, the web 2.0 and the blogosphere do not make professional art criticism redundant, although they may well make the employed art critic a rarity, turning every one of us into a freelancer, hyperlinking between papers and webzines and blogs and podcasts and symposia. They do, however, change the rules of the game. Just as there are certain things a newspaper does better than a monthly magazine and vice versa, there are things more befitting a blog than a printed piece. We have been experimenting with the possibilities of open (source) criticism on “Notes on Metamodernism,”6 an online platform. A couple of years ago we reopened the debate on post-postmodernism, which was all over the place, yet seemed to be going nowhere, by publishing an overtly naive and obviously flawed article that goes by the same name. Nowadays it serves as some kind of ‘stub,’ to put it in Wikipedia’s terminology, of a collaborative research platform that is maintained by several editors, carried by dozens of contributors and attracts hundreds of interested readers a week. This could have only been possible precisely because the initial article-cum-stub was intended not as an authoritarian voice but rather as an open invitation to discuss the matter anew, and, ironically, because it was quite obviously still very much flawed, leaving many issues in contemporary aesthetics and culture underdeveloped or unexplored.

There are many benefits to this type of open source criticism. It allows for the inclusion of a plurality of voices from experts within specific disciplines as much as it promises a discussion of the crossovers, similarities and differences between the disciplines. It also provides the flexibility needed to come to terms with our rapidly changing, interconnected world, as individual pieces are adjustable and expandable when new insights and developments arise. Yet it can also be an excruciating experience. For any form of open, collaborative research needs to organize its own criticism and accept analyses that may not be in line with one’s own intuitions, thoughts and concepts. It also means that this or that line of research is in a state of ‘permanent Beta,’ which means not only that the work is never finished but also that it may become chaotic, sprawling and directionless.

Whatever its benefits, limitations and pitfalls, the emergence of collaborative research projects signal that the age of the individual genius, authoritarian voice and ivory tower intellectual is waning. This is not to say that we are cheering this development, nor that critics should go completely ‘Andrew Keen’ on blogging. It merely is an observation.

WHICH SIDE ARE YOU ON?

Our 21st-century networked mediascape, meanwhile, is changing the ways in which we perceive, think and, most importantly, act in a world that requires acting more than ever. This is a commonplace occurrence, of course. Yet the proliferation of information, and communication technologies, and of its associated plethora of screens large and small, is ushering in a network logic that is decidedly different than the television logic of postmodern times. Any proper analysis of the effects of these new technologies on the arts and our culture (and vice versa) would require a lengthier entry. What interests us, here, however, is how new media are affecting our politics or, rather, our capacities to make the decision to act politically in the first place. To illustrate our point, it would be particularly instructive to compare, yet again, a postmodern text and a metamodern piece. We are thinking of the video wall of the Korean-American video artist Nam June Paik, the postmodern video artist par excellence, and a recent video installation by the artist Annabel Daou, which was featured in the “Discussing Metamodernism” exhibition at Galerie Tanja Wagner in Berlin.

Paik’s Electronic Superhighway (1995), which can be considered the culmination and pinnacle of an oeuvre made up of television statues, cascades, gardens, etc., consists of 336 televisions tuned into 49 different channels, representing a map of the U.S., with each state outlined by neon. It is, indeed, a massive piece, which even in the 1990s conveyed the sense of exhilarating, mindboggling newness that the television screen, and its constant flow of images, must have evoked in and for the postmoderns. Indeed, as Jameson writes about Paik’s earlier works, these video installations urge the postmodern viewer to do what may have seemed impossible to the generations preceding the postmoderns, that is, seeing all of these screens at once and following “the evolutionary mutation of David Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth, who watches 57 television screens simultaneously.”7 The image of Thomas Jerome Newton (Bowie) sitting in his armchair, relaxed and laidback, as he takes it all in is, of course, particularly well chosen. It encapsulates, quite nicely, a postmodern relativism that preempts any necessity to choose one narrative or perspective over another, either as some kind of Lyotardian strategy to keep sailing across an archipelago of epistemological islands with equally attractive coastlines or as some kind of choice to not make any choices at all, because, well, things are going great in the mass-mediatized comfort zone of postmodern times. In both cases, we are, of course, back at the end of history. That Paik represents the U.S. in all its neon-lit glory, beaming with confidence, exuberance and daytime television, seems, then, to be just quite right.

Yet Daou’s video installation Which Side Are You On? seems to get the current zeitgeist quite right, too. And the differences are striking. It features an old television, a still image, a tape recording of the artist asking the titular question, “Which side are you on?-and a recording of people’s answers to that question. That’s it. Here, the television does not appear as a new, exciting, image-spitting piece of consumer electronics. Quite the contrary. It’s old, very old. Not even outdated but pre-dated. Antiquated. Plus, it doesn’t transmit (when did this word come to sound so antique?) moving images. Not even the subtle lines of a facial expression. It shows a still image of something that reminds us of a confession screen.

As you come closer, you hear a tape recording. It is a recording of the artist asking various people the question “Which side are you on?” along with the answers people have given. Some people take the question seriously, giving answers that popes, presidents and other populists would be proud of, such as “the good side,” “the right side,” “the side of humanity,” “the side of the 99 percent,” and so on. Others think more lightly of it, offering humorous replies such as “my side,” “the dark side” and “the sunny side.” But however serious or lightly the respondents take the question, and whatever their answer, you hear doubt in their voices. You hear uncertainty. The question is straightforward. So why is it so difficult to give an answer?

It seems to us that Daou draws attention to the double-bind that emerges when you are forced to choose a side, even, or perhaps rather especially, if you know that no one side is preferable over another, per se. This double-bind is representative of the situation we are in today. The geopolitical, economic and ecological crises have forced a generation that was always said to have all the options in the world to choose a side, to take a stand. Yet we have all learned that taking a stand is problematic, and we have all grown up not having to take a stand (as encapsulated by Nam June Paik’s installation). Yet as the gap between the elite and the rest widens and the political center disintegrates, we need to jump to a side-at least as a first, knee-jerk reaction.

However, as soon as you choose a side there arise two problems that immediately undermine your position. First, you realize your own complicity in the wrongs you try to right. Fair trade? Some, if not most, of your T-shirts are still being produced in sweatshops. Yet you try. Climate change? You consume as much so-called ‘renewable’ energy as possible, but your car still drives on gasoline. And so on and so forth. It is as one of those signs that we noticed at the Occupy protests said: “I am a hypocrite. But I keep trying.” It seems fitting, then, that the still image is of a confession screen. We are all sinners. And we need to confess our worldly sins so that we can start over and over and over again.

It is fitting, too, that the medium through which Daou transmits this double-bind is a television set that is out of date. Daou’s installation expresses, in other words, a certain nostalgia for a world in which there were no sides to take and everything seemed so straightforward, simple, clear-cut. Nowadays, however, the necessity to take a side is paired with the constant flux of information on the Interwebs-where one always finds more, and often contradictory, reports, op-eds and standpoints, etc.-that makes every so-called informed decision an educated guess at best and a leap of faith at worst. What to do about the credit crunch? Re-regulation? Climate change? Syria? We all feel, to put it differently, that things-i.e. the system, capitalism, democracy, the 1 percent, we ourselves, etc.-need to change. But what exactly needs changing, and how we should go about with changing our everyday lives, is another matter entirely. In a sense, as Žižek once put it, our problem is not that we don’t know enough-rather we know too much.

HISTORY

And so we have come full circle. We indeed witness an acceleration of history. We are of course by no means the only ones arguing for such a thing. We already mentioned that Fukuyama swallowed his pride (an act of intellectual courage that can only be applauded). And Charles Krauthammer, another right-wing conservative thinker, declared, too, that we are now ‘paying’ for what he called our ‘holiday from history’ (though we don’t agree at all with his form of bookkeeping, which basically argues that 9/11 in specific and fundamentalist terror in general followed from a decade of negligence of security issues. It seems to us that we should take the notion of ‘paying’ far more literally in the wake of the various financial crises).8 On the leftist, progressive side of the political spectrum, meanwhile, the defeatism of the 1980s and 1990s has been replaced by a rather more engaging tone. The French philosopher Alan Badiou, for instance, has argued for the Rebirth of History, and the British publicist Seumas Milne, who writes for The Guardian, observed a “revenge of history” in the 21st century.9

Our own contribution to this debate has been the reviving of Immanuel Kant’s notion of history (2010; 2011). We feel, in other words, that today’s spatiotemporal logic is not so much Hegelian as it is Kantian. The metamoderns are not looking back at history to discern a ‘rational’ pattern (that famous ‘owl of Minerva’) and noticing that there are a few loose ends that still need to be tied together, as the modern and postmodern readings of Hegel (or should we say: a certain type of vulgar Hegelians) would have it. On the contrary. Rather, they acknowledge that there is no such a thing as a necessary teleological pattern in history, yet still they project, informed by the past, a regulative idea onto the future. Kant argues, much like Hegel, that natural laws are the single condition and structuring principle of human life. However, he suggests, too, that we cannot know these laws and must therefore assume knowledge of them by historicizing-narrating, that is, indeed, imagining hierarchies and relations between and beyond the human actions they supposedly structure. Kant thus at once says: There is a purpose to history, and we imagine there to be a purpose to history, but it might not necessarily be so. Kant does not contradict himself, but he does not confirm the previous either: The first, schematic statement (there is a purpose) is instantly subverted by a second (but, well, it might only be a purpose to our mind).

Kant uses speculative words such as “hope,” “(as’) if,” and “may” to structure his line of reasoning, implicitly turning every argument into an analogy. The cultural philosopher Eva Schaper has henceforth called Kant’s rhetorics aesthetic.10 Each of Kant’s arguments thus, merely by way of analogy, becomes an argument about a fiction. According to this persuasive interpretation, Kant never speaks about history as such; he speaks about what history might be. The metamoderns are kick-starting history by asserting, against their better judgment, that there is an end-or rather, a plurality of endings-to history. If anything, then, contemporary artists, activists and, importantly, the plethora of people who once belonged to the middle classes are acting “as if” there is logic to history, and “as if” its endings are to be found beyond an ever-receding horizon. For them, history is in a state of permanent Beta.

TOWARDS A 21st-CENTURY ART CRITIQUE

As history kick-starts, so does art. And so should art critics, for we need a new vernacular.

* This text was written for the anthology text The ART of Critique/Re-Imagining Professional ART Criticism and The Art School Critique, edited and compiled by Stephen Knudsen, forthcoming via The University of Chicago Press in 2014. Link to a keynote lecture related to this essay by the authors: <http://vimeo.com/68843224>

NOTES

1. Jerry Saltz, “Sincerity and Irony Hug It Out,” New York, May 27, 2010 <http://nymag.com/arts/art/reviews/66277/>

2. Francis Fukuyama. The End of History and the Last Man. London: Penguin, 1992, p. xii.

3. Fredric Jameson. “‘The End of Art’ or ‘The End of History?’” In: The Cultural Turn. London/New York: Verso, 1998, pp. 73-92.

4. Ibid: 90-91.

5. This results in anything from a latter-day scramble for Africa, regime changes in the Arab world, U.S. hesitations to start new proxy wars, and, even, something as unimaginable, a mere decade ago, as Chinese investors buying stakes in Greek ports or opening factories in the Netherlands.

6. See, <www.metamodernism.com>

7. Fredric Jameson. Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991, p. 31.

8. See <chron.com/opinion/editorials/article/Krauthammer-Paying-for-our-holiday-from-history-2088002.php>

9. Alan Badiou. The Rebirth of History. London/New York: Verso, 2012; Seumas Milne. The Revenge of History. London/New York: Verso, 2012.

10. Eva Schaper. “The Kantian ‘As-If’ and Its Relevance for Aesthetics.” In: Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series, Vol. 65 (1964,1965), p. 219-234.

Timotheus Vermeulen is assistant professor of cultural theory at the Radboud University Nijmegen, where he also heads the Centre for New Aesthetics. He has written about contemporary aesthetics and culture for, among others, The Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, Screen and Texte Zur Kunst and is a regular contributor to Frieze. Vermeulen’s latest book is Scenes from the Suburbs (EUP, 2014). With Robin van den Akker, he is co-founding editor of the academic webzine Notes on Metamodernism.

Robin van den Akker is a cultural philosopher working at Erasmus University College Rotterdam and is co-coordinator of the Centre for Art and Philosophy there. He has written about contemporary aesthetics and culture and the digitization of everyday life for, among others, the Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, Frieze and Monu and acted as advisor for various art exhibitions and cultural events about metamodernism. With Timotheus Vermeulen, he is working on two books on metamodernism and organizing the symposium A Metamodern Marathon in partnership with the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.