« Dialogues for a New Millennium

Interview with Ronald Ophuis

“With the introduction of violence and sexuality the identification with the victim or the perpetrator is stronger and more intense.”

Dutch artist Ronald Ophuis (born in 1968, Hengelo) has, since the late 1990s when I first saw his work in Amsterdam, built up a consistent pictorial oeuvre in which history, memory and narrativity emerge as key elements in a thought-provoking, critical and confrontational artistic practice. Our conversation dealt basically with the state of history painting today.

By Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán - The first show in which I saw your work was in the group show ‘Life’s a Bitch’ at de Appel arts centre in Amsterdam in 1998. The art world has changed a lot since then.

Ronald Ophuis - Indeed, the discourse and the art changed massively. From my perspective, especially the social aspect and the request for a social influence of art on society became much stronger. It also raised a huge gap between the artists with works more suitable for commercial galleries and the artworks made from a more social or societal point of perspective which finds their way to the biennales, and so on.

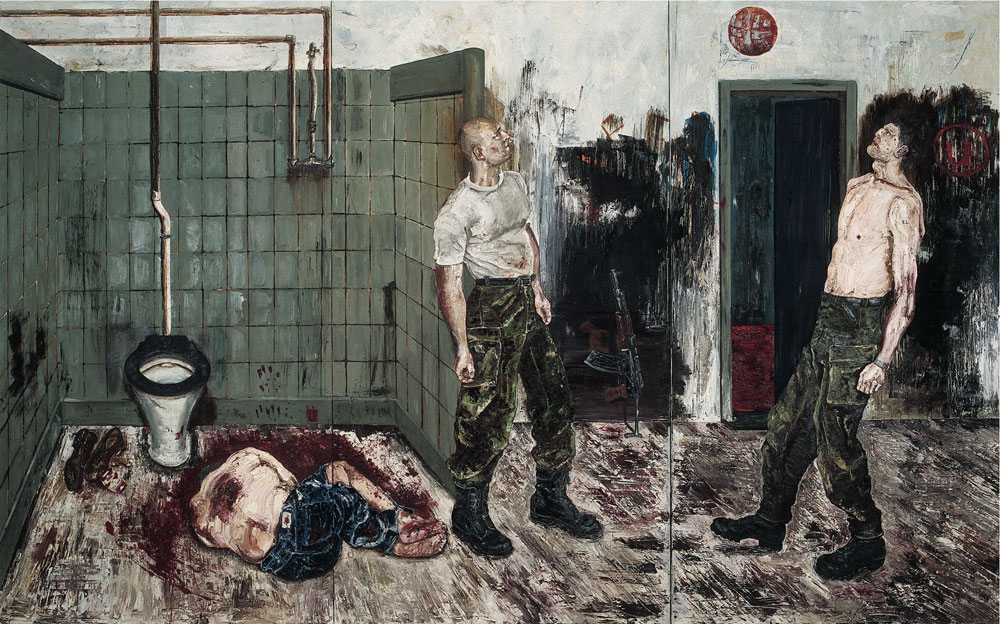

P.B. - One of the works in the show was the-then-and-still-today very confrontational painting titled Execution from 1995.

R.O. - The work was based on the war stories that came out of the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. I imagined a scene where some men were killing the prisoners of war, and they would play with a ball that they found after the killing with the dead body in the background. And, as you could say, ‘One wound tells more than a thousand angels.’ In a way, it’s also a revenge on Mother Nature, a deed driven by fear and of anger towards life. First you have to return the pain and after that there will be time for the giving.

P.B. - Another work was the composition of a group of soccer players violating a boy with a Coca-Cola bottle-Soccer Players–from 1995 as well. What was the inspiration for that particular work?

R.O. - In my childhood this scene happened on my football team. One of my team members was deeply humiliated in this way-an almost classic perversity that exists and dooms groups of men.

P.B. - I remember these two works very vividly. In many of your works-think also of Sweet Violence (1996)-there is a poignant or unapologetic mix of violence and sexuality. Why?

R.O. - Of course, thinking about a scene and trying to find the strongest moment or ’still’ from this story, which is about suffering and then sexuality, is never far away. The interesting thing is that with the introduction of violence and sexuality the identification with the victim or the perpetrator is stronger and more intense. In a way, it is a strong strategy to make a connection between the viewer and the artwork. Which is basically the difference between the ’subjective’ artist and the ‘objective’ journalist: The artist is the one who wants the image, and it raises the question why does an artist want us to see it; the journalist, on the contrary, finds the image and uses it to inform us. It creates an important psychological confusion, when more or less the same image is made by the artist. People ask: Why does the artist want to create this image and why does the artist want me to see it? Which makes the image much stronger when the power of journalistic actuality has disappeared-a completely different position and effect.

Ronald Ophuis, Execution, Srebrenica 1995, 1996, oil on linen, 8.5 ft. x 13.7 ft. Courtesy Gallery Aeroplastics, Brussels/Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam.

FACTS, VIOLENCE, AND PAINTING

P.B. - Resonating with Walter Lippmann’s classical book Public Opinion, maybe then the important question we should ask ourselves here should be: How do we get the facts on which we base our opinions?

R.O. - Thats’s a true mission, because the most important is the how, in which way are the facts presented to us? When do we feel ourselves in the role of a committed witness? Only then we feel the need to judge the facts. We need new judgments. That’s why we create new images and new forms of context in all media by creating a moved witness. Our new or more mediated society also needs new impulses and new strategies to feed the urgency to judge. It is existential to judge over and over, and we can only find or develop these impulses to create new judgments when we don’t think within the boundaries of a fixed morality. A completed and finished morality is a dead end for good humanity in general and for finding judgment for both sides.

And we also have to work on how society wants to remember its history. Many times when there’s a regime change there’s also a change of view of the past. So, for instance, there’s only one small museum in Russia left, which tells about the Goelags, the Russian concentration camps, and then also from the perspective that the inmates were traitors, but you can also mention lots of different other regimes, Rwanda, Indonesia, The Netherlands, etc., and how they try to dominate the view on their history. Historical painting never loses actuality.

P.B. - In contemporary society through social and mass media we see more and more violence-think of ISIS’ videos. Your work is very sociopolitically engaging. What can painting say in this context? Or put differently, why do you prefer to paint instead of using photography or video?

R.O. - It’s the other way around for me. First, I was inspired by the history of painting itself and then the subjects came along. Being a painter is a think-and-act model that fits me. I get irritated by the idea that I have to accomplish an artwork in another medium like video, photography, sculpture, even drawing. I don’t really like it when it has to be more than a study to check ideas out. So I have to take the risk to find out if it’s worthwhile to engage these themes in oil paint in a way that people forget the limitations of painting.

Ronald Ophuis, Girl with Gun, Sierra Leone 2001, 2011, oil on linen, 78.7” x 133.8.” Courtesy Galerie Bernard Ceysson, Paris/ Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam.

P.B. - So if we rephrase the question, why do you prefer to paint? Or what does painting offer you that makes it still very attractive to engage with?

R.O. - That must be the action of painting. Is has been done completely by a human being, whether it is colorful drawing of a child or a beautiful painting done by an artist. When we see a well-painted image we get inspired, and when you are inspired your neurotransmitters cause a reaction of a feeling of deepness, pureness, open mind, and that causes a commitment and meaning to life. So when you are in that state you receive the information or background of the painted scene in another way.

P.B. - I am of the opinion that your whole oeuvre is a critical rewriting of the grand genre in a 21st-century perspective: History painting from a critical, anti-didactic and even anti-history perspective. It’s rather surprising because since at least for a century history painting has fallen out of favor. Why do you think?

R.O. - A question for me too. When I was a kid, I was always already drawing scenes, so for me it was logical to follow this road. Somehow we also believe the suffering or action on a painted image. It was never Christ himself who posed for a painting, but a body-double, but we still can easily believe in his suffering. And I always have the existential idea that historical thinking enlarges the meaning or experience of life.

P.B. - Maybe the disappearance of the influence of academies of art through the training of young artists had something to do with it?

R.O. - Sure, that must have played an important role, but still I don’t get it why there aren’t more painters working in this tradition. It is such a rich tradition with still new possibilities.

NEW POSSIBILITIES OF HISTORY PAINTING AND PHOTOGRAPHY

P.B. - In which direction do these new possibilities go that you are thinking about?

R.O. - New stories, new aesthetics and still the viewer is schooled by the tradition on how to read historical paintings, which gives you an advanced change, the viewers understand the newly used possibilities immediately, because they can compare it to the collected image of the historical painters from earlier times. So, from storytelling painter Giotto to Gericault you don’t only judge the beauty and the story, but also the differences between these two painters. So tradition adds.

P.B. - How did your interest in history painting get triggered?

R.O. - Being raised as a Catholic we weekly went to the services in the church, especially the church in the village of my grandmother, which had some amazing frescoes telling the story of the Via Crucis. During the service I was totally into that story and tried to take different positions, an emotionally overwhelming experience. At the age of 17 my father gave me a part of his working place and built an easel for me. Then I was much more inspired by the works of Willem de Kooning, Antoni Tápies, Emil Schumacher, etc. But at art school we went during the first year to Paris and I got to see Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, and that did hit me like no painting before. That was the real trigger to work in this tradition.

P.B. - Most painters that have tackled the genre, like Luc Tuymans, Gerhard Richter, even Marlene Dumas in some of her latest works, paint directly from a photograph; that is, they reproduce the scene depicted in the photo. Isn’t that a little old fashioned? Aren’t we able at this point to create a whole new image instead of re-creating it?

R.O. - The painters you are mentioning are masters in choosing the right image and are satisfied with the found or chosen existing images. They also have an amazing hand when painting and are more focused on an authentic aesthetic gift. So it works for them, they don’t want more. I want to work completely differently. I start from texts written by historians, journalists, writers, poets. I watch documentaries, movies. I collect the images of a certain theme in the media, old images, new images. I try to collect stories from the people who got involved in the conflicts I am painting about by doing interviews with them. I visit the places where it happens, make my own documentation at the places where it happened, if necessary build the decors in my studio, have the clothes made for the actors I use to stage the drama.

I always feel the need to stage the scene. I can’t find the images that pop up in my thoughts through imagination. I need to work with actors/models before I can start, and I believe in the idea that a fictional image tells the story with truth and power-you can lie about the truth.

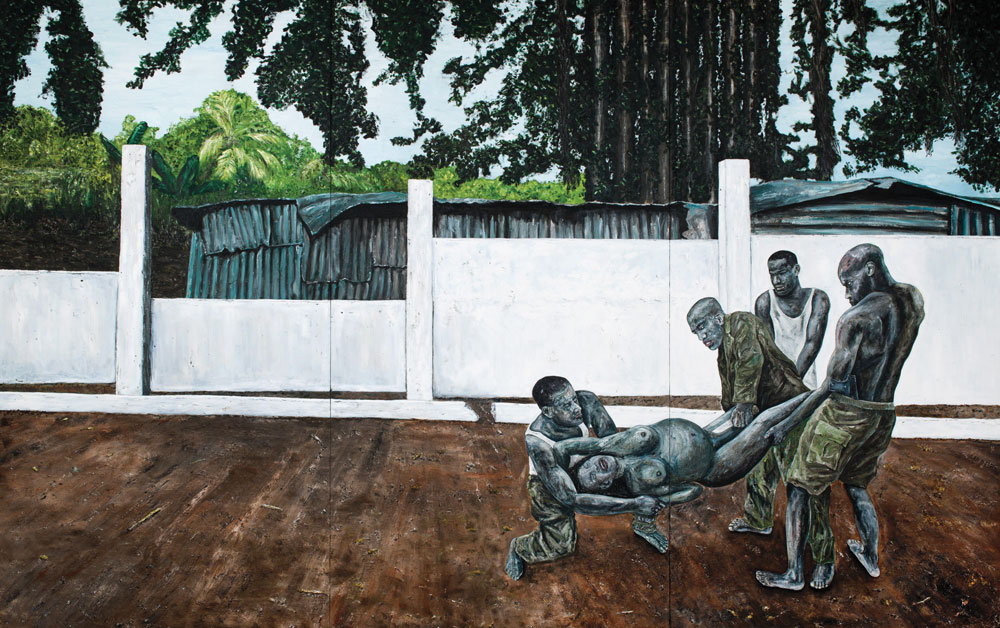

Ronald Ophuis, The Bet, Boy or Girl, Sierra Leone 2001, 2014, oil on linen, 133.8” x 212.5.” Courtesy Gallery Aeroplastics, Brussels/Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam.

P.B. - Let’s delve a bit more into your modus operandi. You use a mix of images from mass media and a staging with models to create the image you’re looking for.

R.O. - Mass media is a check-out context to me to find out how certain themes are already visualized, and this provides me a visual context. But I also depart from written words, literature or journalism and the interviews I take. And most important, I like to think in images instead of searching for the right already-existing image. Through thinking and sketching, developing a more or less new image is something I really enjoy, and it gives me the feeling of freedom, of no boundaries. Then I’m productive in my mind and checking my feelings and intellect through the new images that I imagine. The idea starts to develop.

In a way an idea is always perfect. Just at the point when you make it visible through a simple drawing you create a problem that has to be solved. I like that challenge as a mind and emotional game. It creates new images, thoughts, feelings. I get closer to myself, more confronting to myself.

P.B. - In the exhibit I saw at Galerie Bernard Ceysson in Paris in December 2014, you started to push the limits between abstraction and figuration -think of the flower series for example. Can you elaborate on this?

R.O. - In my earlier paintings I always took the chance to paint some flowers in the background whenever it was possible. I always enjoyed painting flowers, but also to look at the painted flowers. When I travelled through the former Yugoslavia collecting stories and images, I photographed the flowers which were growing on the mass graves around Srebrenica (Bosnia and Herzegovina), the place where the Serbs killed more than 7,000 Muslims in 1995. I started to paint these mass grave flowers back home. The last year I felt finally free enough to paint just wild flowers, without a direct narrative story, and I have to admit I was always truly a fan of the flowers Manet painted at the end of his life when he was so ill he hardly could do much more.

Ronald Ophuis, Miscarriage, 2014, oil on linen, 102.3” x 78.7.” Courtesy Gallery Aeroplastics, Brussels/Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam.

P.B. - And another direction in your practice has been the introduction of parts of photographs in your pictorial narrative in which you then intervene. Is this interaction with photography something you’re eager to explore in the future? Has it to do maybe with the slowness of painting itself?

R.O. - For years I was looking for a way to use the photographs that I make from the actors/models in my studio. I always find them very inspiring, these sketches. And now I found a good way to use them sometimes in an artwork that I think is strong enough to be on its own. Only showing the photographs didn’t work, because they were studies and meant to be studies. They work in a catalogue as extra information, but not on an exhibition wall. Now they do, combined with other images and some painted details. But still they are just details in the total oeuvre.

P.B. - As a final remark, would you agree that between then and now your work still has this confrontational edge but has become more subtle, less direct? I think of works like Marches Funebres or the more recent Arab Spring. On their way to their Revolution. Syria 2011, 2014.

R.O. - When the years of painting passes by, you don’t only think of what you want to make next, but you also start thinking of your next work in perspective to your oeuvre. Not again the same stories-your sensibility for other moments somehow develop. The violence is still existing and will never be far away, but also in the longer past there were works with a more subtle perspective on violence.

Paco Barragán is the visual arts curator of Centro Cultural Matucana 100 in Santiago, Chile. He recently curated “Intimate Strangers: Politics as Celebrity, Celebrity as Politics” and “Alfredo Jaar: May 1, 2011″ (Matucana 100, 2015), “Guided Tour: Artist, Museum, Spectator” (MUSAC, Leon, Spain, 2015), and “Erwin Olaf: The Empire of Illusion” (MACRO, Rosario, Argentina, 2015). He is author of The Art to Come (Subastas, 2002) and The Art Fair Age (CHARTA, 2008).