« Reviews

Agnes Martin

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum - New York

Decoding Agnes Martin

By Kim Power

Diogenes of Sinope (c. 412 - 323 B.C.) was fabled to have carried around a lantern in daylight. When questioned as to this practice, he replied he was looking for “an (honest) man.” Canadian born, American abstractionist, Agnes Martin (1992 - 2004) certainly fits the bill, albeit not the gender. Often labeled a Minimalist painter, close inspection reveals the false generalization of this claim. The Pragmatist philosopher John Dewey states “Art is a selection of what is significant, with rejection by the very same impulse of what is irrelevant, and thereby the significant is compressed and intensified.” (Art as Experience, 1934). Intensely concentrated and reduced to the most elemental of design principles, Martin’s paintings lack the hard edged industrial quality of Minimalist artists such as Donald Judd (1928-1994), Robert Morris (1931-present), Dan Flavin (1933-1996) and Frank Stella (1936-present), preferring a softer “emotional” application. Nonetheless, Martin’s pared down use of geometry, symmetry and structure set her apart from the Abstract Expressionists she aligned herself with. Sandwiched between the two parallel movements, Martin evades categorization, forcing the viewer to take her work at face value.

The exhibition “Agnes Martin” bears witness to a lifetime of dedication to purpose. The Guggenheim is the fourth in line to exhibit the retrospective. It was first displayed at the Tate Modern in England in 2015. Following that, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, Germany and The Los Angeles County Museum of Art were, respectively, both hosts to the exhibition earlier this year. Displaying more than 115 paintings and works on paper (fifteen of which are solely part of this New York version of the retrospective) the exhibition is an impressive tribute to Martin’s prolific career.

The exhibition, co-curated by Tracey Bashkoff, senior curator of collections and exhibitions and guest curator Tiffany Bell, includes artworks from the 1950’s until just before Martin’s death at ninety-two in 2004. Bell has spent six years accumulating and editing research that will culminate in the upcoming Agnes Martin Catalogue Raisonné to be published digitally by Artifex Press. According to Bell, the initial publication will focus on Martin’s paintings to be followed later by her drawings. Bell was also co-curator of the retrospective at the Tate along with Frances Morris, the Tate’s new director.

Set in the vertiginous interior of the Guggenheim, Martin’s striped and gridded paintings are reinforced by the helical architecture through which they are seen, structure and image supporting each other in an echoing sympathetic resonance. The effect is bold yet softened by the dulcet tones of Martin’s limited palette of neutrals, earth tones, pastel blues and oranges, further muted by the filtered natural light afforded by the museum’s oculus. The cathedral-like effect enhances the meditative quality of the works.

There is a sense of religiosity in the ritualistic production of Martin’s work, though both Bashkoff and Bell are quick to correct any assumption that it is meant to be “spiritual.” Humanist author Nancy Prinsenthal’s citation of a letter written by Martin in 1977 (addressed to her art dealer and Pace Gallery founder Arne Glimcher) supports this caveat. In the letter, Martin states, “There is no spiritual. There is the concrete and the abstract.” (Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art, 2016) Later, in Leon d’Avigdor’s documentary film Between the Lines (2002), Martin states, “I have my own religion. Suits me, I made it up myself-It’s a secret religion-It’s about love, not God.”

A teacher, a painter, a sage to some, Martin pursued a vision inspired by her own intuitive thought process. Jose Ortega y Gasset, a Spanish philosopher of the 20th century, stated in his book What is Knowledge (2002) that, “Thinking is a swimming motion one engages in so as to be saved from being at loss in chaos.” For Martin, this metaphor is doubly apt since she was not only a strong and athletic swimmer but also suffered from schizophrenia. Though subject to hearing voices and having bouts of mental confusion, Martin persevered throughout her life to produce an extraordinary number of artworks, many of which she, like Shiva, destroyed because they did not fully embody her vision of true abstraction.

It is hard to say what it is that makes Martin’s work so mesmerizing. Its simplicity seems so obvious. Martin’s own words: love, innocence, happiness and freedom present platitudinous ideals that would ring shallow if not for the sincerity of her pursuit. They imply the intent of transcendence over the material aspects of reality yet Martin’s practice lies firmly in the concrete. These notions might be further elucidated when looking through the lens of progenitors of abstract expression such as Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian whose Neoplatonic philosophical belief in transcendence of the representational realm was the driving force behind their creations. Traces of influence from Mondrian’s grids to Malevich’s White on White (1918) can be directly seen in Martin’s work. In a sense, the grid was Martin’s personal gate key to speak about the ephemeral without direct confrontation and provided her with a platform to express, as art historian Rosalind Krauss so well put it in her well known essay Grids (The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, 1985) “a secular form of belief.”

An able bodied builder, Martin constructed her own home in New Mexico in 1968, built out of adobe brick Martin cast it herself and laid with the help of her University of Albuquerque students. Later on Martin would build a log cabin from trees she felled with the use of a chainsaw. While she would deny that the experience of construction had anything to do with her artworks, there is an undeniable congruency between Martin’s tools (a ruler, pencil, level, ladder, brush and paint) and methodology of constructing her structural drawings and paintings (which she mathematically calculated down to the last detail and executed in fine order) and the manual labor, planning, and fabrication of a skilled mason or carpenter.

Martin was a pragmatist and her process reflected that quality of her personality. In Joan Simon’s article for Art in America, “Perfection is in the Mind: An Interview with Agnes Martin” (1966), Martin reveals that she consistently painted all her stripes vertically, no matter the orientation of the finished painting, due to the dripping that would occur in her application of thin washes of acrylic paint. Martin also stated that she stopped working on six feet square canvases (which she adhered to for thirty-two years) in favor of a smaller five feet square format simply for the practical reason that the larger size became too heavy for her to carry.

If I were asked to give one clear defining characteristic of Martin’s work, I would have to choose her deep understanding of spatial awareness, which is evident throughout her entire career. This quality is richly enhanced by the strategic curatorial plan laid out in a rhythmical, largely chronological, fashion. The works are given space to breathe and seem to expand within that space.

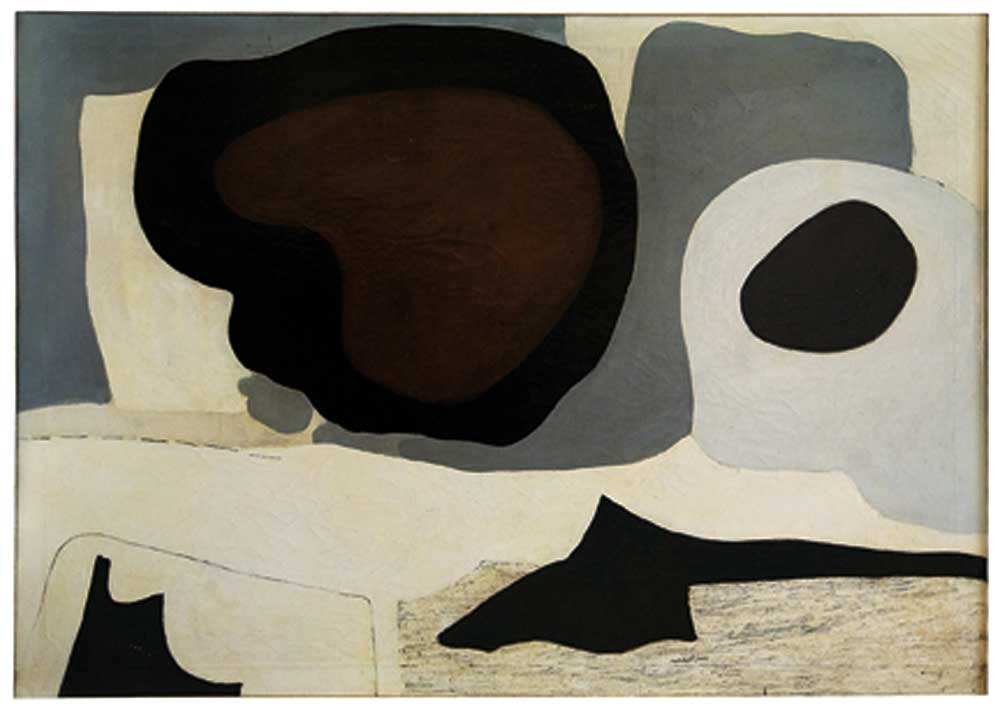

At the exhibition’s point of departure, one of Martin’s earliest paintings, Mid Winter (1954), displays merging biomorphic shapes which suggest a mountainous landscape, not unlike the New Mexican terrain she so loved, described in neutral greys, beige, black with burnt umber for the center of an amoeba-like sun. Martin’s interest in line as a defining element is already made manifest in her employment of a narrow and black contour line which surrounds an opaque, black, semi-triangular shape in the left hand corner of the picture plane. The top three quarters of the painting is almost oppressive with its weight of abutting and overlapping forms, challenging assumed expectations of fundamental physical properties of earth and sky.

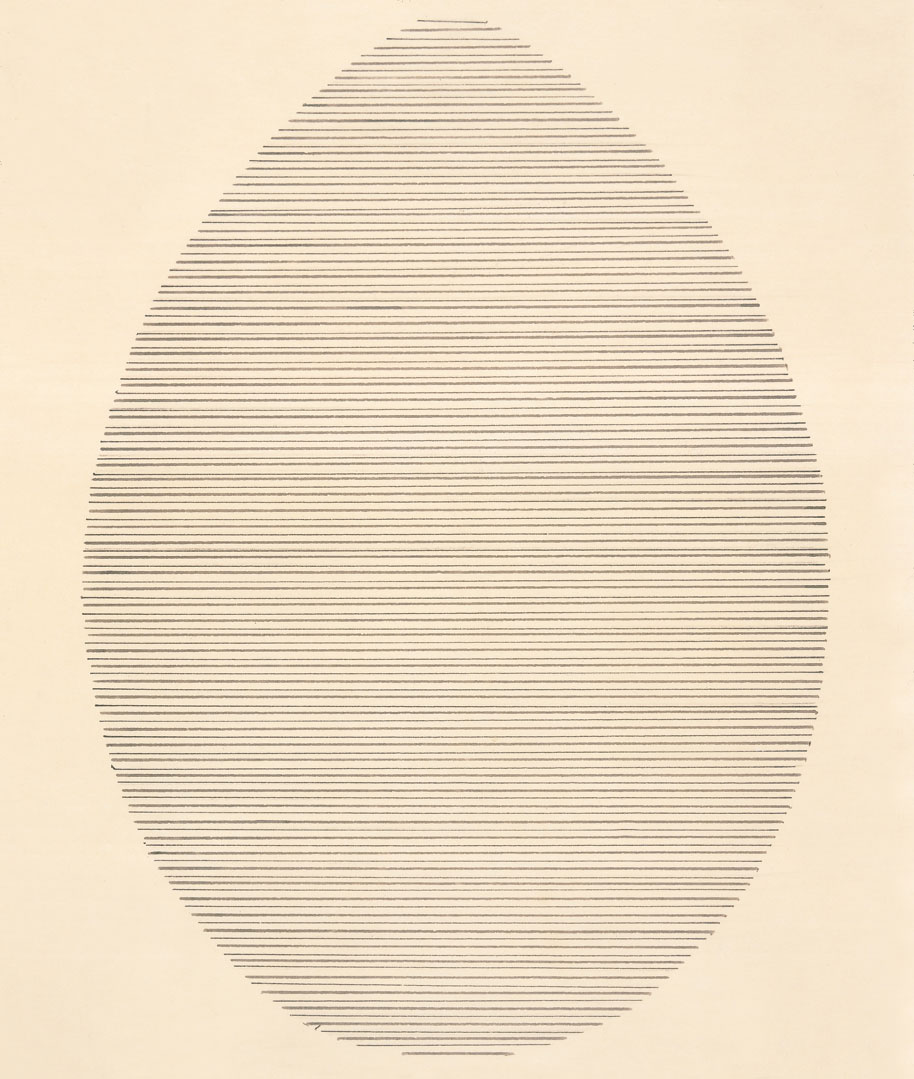

Employing the use of the horizontal line, but yet to abandon form, Martin created The Egg (1963). I find it interesting that she chose this iconic symbol that holds such weighty associations, such as fertility and primordial creation. It could easily be seen as a portent to the fecundity of Martin’s art production. Drawn in lines of ink in varying and irregular thicknesses, with no systematic pattern, tight interstices left open by the lack of an enclosing outline breathe in a hallucinatory vibration of optic tension.

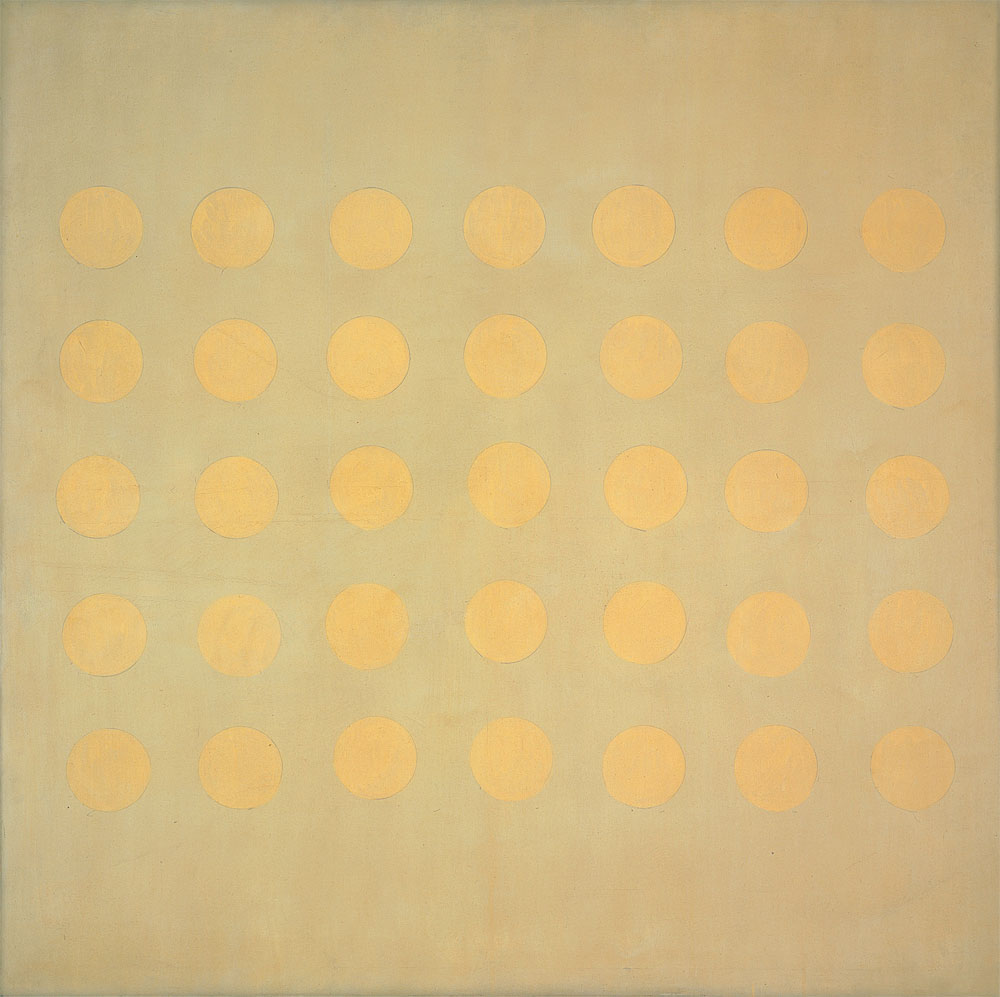

Martin achieved a similar effect with her painting Buds (1959) five years earlier, this time including color. Thirty-five circles (seven across and five down) painted in yellow ocher oil paint are each encircled by a graphite line. Applied with what appears to be some sort of compass, their outlines break open and are scribed with an uneven pressure on a greenish taupe foundation that shows traces of the yellow ochre. You can feel that Martin is already rebelling against the circle. Martin’s poem The Untroubled Mind (1973) states her opinion in no uncertain terms, “-I don’t like circles - too expanding-” (1973). In Bell’s essay Happiness is the Goal (Agnes Martin, 2015), she describes this painting as a progenitor of Martin’s later grid paintings. In this preliminary experiment of Martin’s, the lozenge forms act alternately as holes or spots, additionally pushing the awareness of not only the planar space but dimensional space as well.

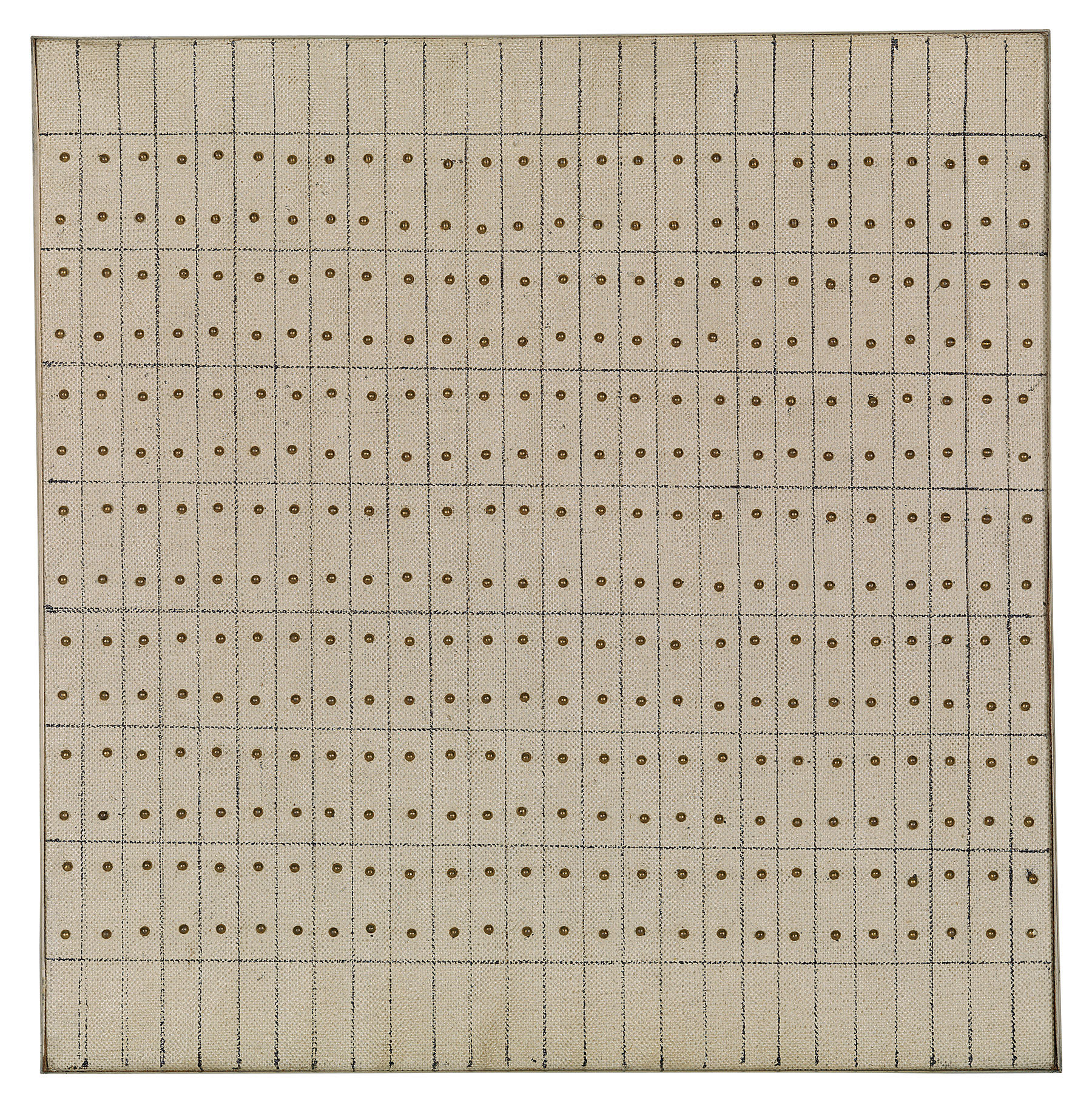

While Martin credits The Tree (1965) as her first grid painting, there are smaller experimental works that show she was thinking of the grid much earlier. Little Sister (1962), a mixed media piece, is made up of 182 small vertical rectangles in a grid (twenty-six across and seven down, not counting a row above and at the bottom as well). The cells are occupied by two dots. The museum’s label clarifies that they are brass nails. Without stretch marks or shadow play, there are no signs that, in the dim lighting afforded by the display, identify the dots as consisting of other materials than paint or graphite. The lines are drawn in ink on a taupe ground. Traced by hand, the grid is not anything near precise. The nails (spaced ‘by eye’) and the imprecise grid have a hallucinatory effect in that they signify order but are in fact only an allusion to it. This use of subtly subversive, illusionary techniques in Martin’s works, including floating grids and wavering lines, implicate involvement of the hand versus machine. The impression is one of an undercurrent of movement within a static image.

The format of Little Sister is not quite square (measuring 9 7/8 inches on one side and 9 11/16 inches on the other). One can see that Martin had not yet formalized her methodology of offsetting what she described to Simon as the “authoritative” square with smaller rectangles. Martin later expounded upon this thinking in her essay Answer to an Inquiry, writing, “When I cover the square surface with rectangles it lightens the weight of the square, destroys its power.” (Agnes Martin: Writings/Schriften, Dieter Schwarz, Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 1992). One wonders if this rebellion against the self imposed restriction of the square is personal, given Martin’s strict upbringing and her inability or unwillingness, or both, to fit into the strictures of society. A solitary character, Martin’s personal relationships often went the way of the dodo.

Martin’s commitment to working in a square format seems equally as pivotal as her discovery of the grid in her development of a clear visual language. Working in the set parameters of a defined compositional space along with the restriction of working with only vertical and horizontal lines and stripes, effectively allowed Martin to explore multiple permutations ad infinitum. Again Dewey, though not an advocate of abstraction, seems to have touched upon what is elemental to Martin’s practice. He states, “lines express the ways in which things act upon one another and upon us; the ways in which, when objects act together, they reinforce and interfere. For this reason, lines are wavering, upright, oblique, crooked, majestic; for this reason they seem in direct perception to have even moral expressiveness.”

Martin manipulates lines like a statistician juggles numbers, reducing and expanding their relational distance in a visual description of space and time. These two elements become a fugue that connects her works from the moment she discovered the grid and committed to line as a methodological tool, to her last paintings, almost without exception. In many ways you could almost say she was continually painting the same painting, yet somehow the effect is not one of a dull, monotonous hum, but rather an ongoing symphony of melodic expressions.

A phrase of this orchestration, created in Martin’s last years of production, Untitled #5 (1998) is perhaps one of her quietest paintings, which, considering the subtlety of her works is saying quite a lot. It has elements of the color field painters in its diluted acrylic lemon yellow, delft blue and salmon pink bands of color washes that, though separate, appear to merge as one. Graphite lines drawn over the acrylic paint appear and disappear into the ether. Applied in Martin’s characteristic gesture of uneven pressure they are permeable membranes that implicate the movement of the hand through time and laterally through space while the atmospheric quality of the paint creates the impression of dimensional travel. While many of Martin’s paintings can easily stand on their own, #5 seems to be stronger in relationship to and supported by its younger and older brothers and sisters. Interestingly, Martin’s life, lived in solitude for many, many years, reflected a parallel relationship in her decision to move to Taos, New Mexico in the early 1990’s. As she told Simon in the aforementioned interview, “I decided that human beings are herd animals. And I decided that to live properly you stay with the herd.”

I would be remiss if I were to neglect to speak of The Islands I-XII (1979). Staged in a side room on their own, these seven paintings, each subtle variations of each other in stripes of white on white, with narrow to wider bands of white on grey blue, are virtually impossible to document photographically. No matter, any photographic reproduction would not do justice to the experiential power that they invoke. Stripes created in layers of thin white wash over the grey are integrated with varying widths of wider opaque white bands, built up with thicker paint applied in inconsistent brush strokes. They are meant to be experienced together as a whole. Graphite lines are close and double, then single again. The effect is one of entering into a cloudscape, disembodying. You lose the sense of space and time. Watch your step as you exit. This series is by far the most compelling and most reductive of Martin’s paintings and, I believe, sums up the essence of her pursuit of total non-objectivity, yet she went on.

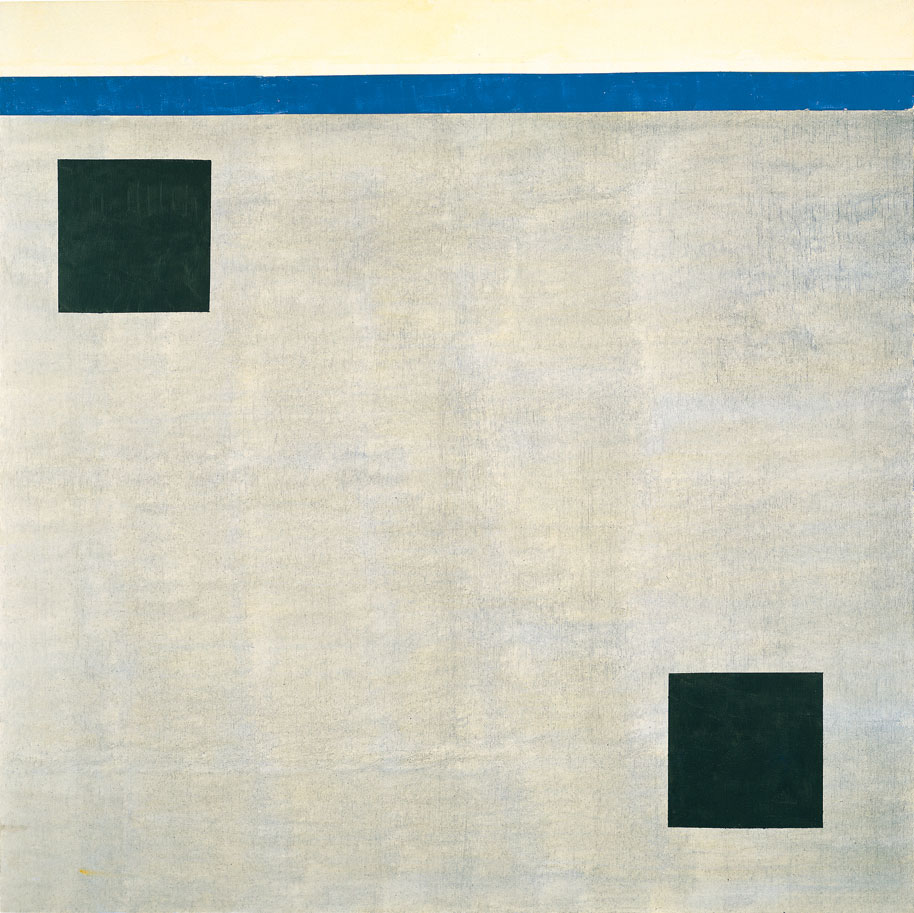

One of Martin’s last paintings, Untitled (2004) has no number to delineate its place in the hierarchy of her works. It would be easy to project associative interpretations on this painting in the context of Martin’s last days. The two blocks, different and yet the same, could be Martin’s final confrontation of her self and her mind (which she often spoke of almost as if referring to a separate entity). Martin would ask her mind for permission to make major life decisions as well as for her next inspiration, sometimes waiting several months for an answer. The top block on the left hand side is fractionally irregular while the bottom right block appears square. They seem to float or hover over a sea of uncertainty or vast unknowable space. An approximately two-inch stripe of patchy ultramarine blue rests like a cushion between this larger void and a wider stripe of light beige just above it, twice its width. This insertion gives rise to interpretations of this work as landscape, not actual but metaphysical, with the top stripe acting as an expanse of sublime light from above. The blue and yellow intermix in the larger portion below, showing traces of horizontal and vertical brushstrokes.

After years of focusing on the visual koan of line and space, this return to geometric shape might appear a retraction or regression but the addition of the stripe implicates that, rather than a step backwards, it is a synthesis and perhaps the beginning of a new thread of investigation. We will never know. Much like her lines that often did not reach the end of the canvas, signaling continuity and defying borders, Martin leaves the door open to conjecture and possibility. There is still a light ahead in the distance. Look.

(October 7, 2016 - January 11, 2017)

Kim Power is an artist and writer currently residing in The Bronx. She holds a B.S. in Art Education from James Madison University and a Master in Fine Arts in painting from the New York Academy of Art. Her reviews have been published both online and in print through The Brooklyn Rail, Arte Fuse, and Quantum Art Review.

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.