« Features

Allora & Calzadilla: Ironing a Camel’s Hump

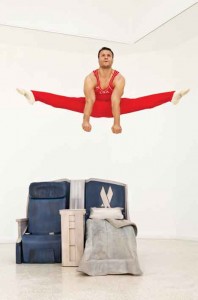

Allora & Calzadilla, Body in Flight (American), 2011. Performance by gymnast David Durante at the U.S. Pavilion, 54th International Art Exhibition. Photo: Andrew Bordwin

The U.S. Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale provides a good argument to look into Puerto Rico-based artists Allora & Calzadilla’s proposal and how the mechanisms of political art are incorporated into the market and finally neutralized.

By Carla Acevedo-Yates

Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla are a collaborative artist team based in San Juan. Having worked together for over 15 years, Allora & Calzadilla develop works that reconfigure meaning by questioning the ways we relate to familiar objects, sounds, and gestures, while referencing social, economic, and political themes. They were selected by Lisa Freiman of the Indianapolis Museum to propose a project for the U.S. Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale. A politically correct choice by the U.S. Department of State, their implication in this mega art event raises important questions regarding the current state of political art, representative art events, and artist denominations. An interview for ARTPULSE reveals even more.

Reflecting Puerto Rico’s political and cultural double life, Jennifer Allora (born in Philadelphia) and Guillermo Calzadilla (born in Cuba, but raised in Puerto Rico) are emblematic of the dislocation that Puerto Ricans face as one of the oldest colonies in the world.

Their early projects, which progressively gained international attention, were concerned with the political situation of Vieques, a small island off the east coast of Puerto Rico, a land that was expropriated from the people of Puerto Rico and used by the U.S. Navy as a bomb-testing range for well over 50 years. Projects such as Land Mark, Land Mark (Footprints), Returning a Sound, and Under Discussion all address these issues explicitly. Working with local left-wing activist groups and supporting their civil disobedience campaign against the U.S., these works evidence the military exploits of the U.S. on the island while making them known to a larger audience. Nonetheless, and as recent projects attest, their works are seemingly moving toward a more neutral and safer ground, foreshadowing perhaps the emergence and establishment of a commodified political mainstream.

Relatively new on the international art scene, many were surprised to hear that Allora & Calzadilla were selected to succeed Bruce Nauman to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale. Their proposal for the U.S. Pavilion, titled Gloria “looks at themes such as militarism, nationalism, sports, competition, and religion” (Allora and Calzadilla Apr. 2011). Among six new commissioned works are Track and Field, an upside-down military tank with a running treadmill on its right track, and Body in Flight (Delta) and Body in Flight (American), a carved and stained wood replica of a commercial business-class airplane seat that functions as a support for a gymnastic/modern dance routine. Jennifer Allora comments: “The sinuous curve of the Delta seat we felt could make for an interesting new version of the balance beam, while the more rectilinear and blocky nature of the American seat seemed to us an interesting substitute for the pommel horse” (Apr. 2011). Both of these works are paradigmatic of Allora & Calzadilla’s practice in that they create unexpected juxtapositions of familiar objects or actions in an attempt to create a new visual language. In this particular case, the idea of competitive sports is coupled with symbols of U.S. power relations; one can assume that a military tank is just as much of a commodity as a business-class seat. The result of this odd combination is a visual metaphor that seemingly presents a critique of the Biennale and growing nationalism. One can safely assume that the Venice Biennale is the Olympics of the art world; an event where artists are but mere gymnasts twirling to the tune of a controlled routine. And they themselves have perhaps inadvertently fallen into this trap.

THE U.S. PAVILION AT THE 54th VENICE BIENNALE: COMPLACENT GLORY

In a personal interview conducted in San Juan in April, 2011, for ARTPULSE, Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla spoke about their projects for the Biennale and other relevant subjects, but then backed down on most of their answers when reading the written transcript. After various revisions from both artists that attempted to change the dynamics of the interview, the interview didn’t go to print, since many answers were eliminated or edited down to the point of complete distortion. The fact is, as much as they would like to appear as proponents of criticality and dialogue, they are very cautious with the way they project themselves to the media. In our interview, when mentioning to Guillermo Calzadilla that he would represent the U.S. in the Venice Biennale, he responded: “It’s impossible for me to represent the U.S. It’s a very complicated process, and the more I try to fully represent myself, since it’s constantly changing and transforming and becoming, the more ridiculous and absurd it is. So if I cannot represent myself or somebody that I know, like Jennifer or a family member, how can I say that I can represent a nation?” (Apr. 2011) The new version of the interview elicited a more ambiguous response. In it, Allora wrote: “What we have made should count as only one of an infinite number of ways that the U.S. could be represented.” To which Calzadilla responded: “Right. If I cannot represent myself, fully and completely, how would it be possible to represent an entire nation?” (May 2011)

Body in Flight (Delta), 2011. Performance by gymnast Rachel Salzman at the U.S. Pavilion, 54th International Art Exhibition, presented by the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Photo: Andrew Bordwin.

Denominations were also discussed, which raised questions and challenged previous interpretations of their work. Both seem adamant in avoiding being identified as political artists, although this is clearly the medium they have been working with since early on in their careers. “We don’t want journalists to quickly label us as political artists -Allora suggested- because if they do then every other reading that we could possibly have on our work is going to be closed down immediately. And we are interested in a lot of other things that are not political in addition to the political dimension of art.”(Apr. 2011) But when reflecting on Allora & Calzadilla’s works, particularly their projects for the Venice Biennale, thinking about politics is inevitable, as the works are politically motivated. “That is the very medium we are working with -Allora stated- we are not shying away from it” (Apr. 2011). However, their final edited version provided a more cautious statement: “We have taken ideas of nationalism, competition, war, and global commerce as the subjects of the work, so we can see how you might come to that conclusion” (May 2011). This seems slightly detached and equivocal, perhaps because it’s somewhat of a contradiction that they are representing the country they once denounced in previous projects. In any case, they come across as being quite reluctant to implicate themselves in their work.

Even if an attempt is made to elude any type of political classifications, curator Lisa Freiman has acknowledged that the projects are “intentionally political”1 and probably chose them as protagonists for her proposal precisely for that reason. The political climate in the U.S. was right and they seem to perfectly fit a very specific profile; a collaborative team living in a politically ambiguous U.S. territory, performative and politically engaging work. According to a press release from the U.S. State Department, “the work of Allora & Calzadilla, a Spanish-speaking team living and working in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, reflects the progressiveness of creativity and culture in the United States today,”2 which seems like a very politically correct choice for the U.S. post George W. Bush. To this effect, artist labeling and regional classifications are important as Allora admits: “This is the first time that we have been considered American artists because we are doing the U.S. Pavilion, but in a way we have been probably selected because we live in Puerto Rico. I’m sure that if we were in Idaho, for example, we wouldn’t have been as compelling candidates” (Apr. 2011). This response was consequently substituted with a more circumspect remark: “It would seem that our relationship and work complicates those classifications” (May 2011). On a side note, it just so happens that President Barack Obama signed an order to renew the President’s Task Force on Puerto Rico’s Status. The report, published on March 2011, brings once again into question the controversial Insular Cases (1898) that deny Puerto Ricans residing in Puerto Rico full constitutional rights as U.S. citizens (Monge). It is only when abroad, living in the U.S. or any other country for that matter, that they gain full rights (such as the right to vote in U.S. presidential elections). This could have been perhaps a more compelling topic to discuss within the context of an international arena such as the Venice Biennale, given that most of Allora & Calzadilla’s early work focuses and capitalizes on Puerto Rico’s political predicament.

DOWN WITH THE ART OF THE “PADRONE”

Biennials are no strangers to politics or attempts at political artistic manifestations, from the controversial 1968 Venice Biennale, where students barged in the Giardini in massive protest (David Lamelas’ telex machine reporting news from Vietnam and Michelangelo Pistoletto’s withdrawal also come to mind), to the 29th São Paulo Biennial, There’s always a cup of sea to sail in. The latter one, based on the idea that it is impossible to separate art from politics posed interesting questions on this very subject, when chief curators Moacir dos Anjos and Agnaldo Farias covered a work by Roberto Jacoby and the Brigada Internacional that featured two large-scale photographs of Dilma Rousseff, (presidential candidate for the Worker’s Party) opposite José Serra (presidential candidate for the Brazilian Social Democratic Party). Perhaps a more successful political manifestation was achieved during the 2008 São Paulo Biennial In Living Contact when chief curator Ivo Mesquita, allegedly buckling under the pressure of massive budget cuts, decided to leave empty the second floor of Oscar Niemeyer’s pavilion. In a spontaneous act of transgression, a group of Pixadores (an urban art movement in Brazil) invaded the space and created perhaps the most political work of all.

Chalk, 1998/2002, 12 chalks, 12” in diameter x 64” in length each. Performance view: III Ibero-American Biennial (Lima Biennial). Photo © Allora & Calzadilla.

Being the Venice Biennale one of the foremost international art institutions, and in light of the aforementioned manifestations, Allora & Calzadilla’s Gloria becomes a statement of power and excess on behalf of the U.S. When investigating their previous work further, one finds controlled scenarios working behind an activist front. An example is Chalk. Although this project was realized in two different sites with little or no outcome over the course of various years, it was the third time within the convoluted political context of Lima, Peru where the work acquired meaning. Here, local protesters were allowed by the government fifteen minutes each day to go around a public plaza and voice their opinions. The artists placed huge chalks near the plaza thinking specifically of the protesters, who in turn used the chalks to write political messages on the plaza. The scenario that consequently played out included the removal of the chalks and the erasing of the messages by a police squad. Benefiting from an already charged political climate, and making conscious decisions that would empower the work, one might argue whether the protest evolved into a spectacle initiated and controlled by the artists. On a similar note, in the video Under Discussion an alleged local activist creates a makeshift boat out of a conference table to bring into discussion the island of Vieques’ uncertain political future. In reality the ‘local activist’ was neither from Vieques nor an activist (Benavides 97), but a student from the Escuela de Artes Plásticas (EAP) in San Juan, Puerto Rico who was asked to play the part. Although a rather insignificant detail within the larger context of the work and its meaning, the fact that they insist on defining him as a local activist in the description of the work3 is deceptive. Under these conditions, one might also question the work Land Mark (Footprints) and if local activists were involved in the process of creating the work. A predetermined and controlled artistic process doesn’t undermine the political nature of the work, but it does raise important questions.

WHAT DOES THIS REPRESENT?

WHAT DO YOU REPRESENT?

An unrestricted and responsive dialogue must be maintained at all costs and at every level. Is critically engaged work free of discussion? Has the politically correct entered the mainstream under the guise of the politically engaged? It would seem that Allora & Calzadilla’s elaborate and costly scenarios for the 54th Venice Biennale embody today’s insatiable obsession with the spectacle. According to Allora, the title Gloria “alludes to the pomp and splendor of Venetian palaces” (Pérez Rivera). It also alludes to the project’s hefty price tag of well over $1 million, including an undisclosed amount of U.S. tax dollars. But besides the amount of money invested, what do these works really represent? A glorious critique or a glorification of U.S. power? Reactions to the projects have spanned the spectrum. “Now that’s America,”4 was Jerry Saltz’s initial reaction to Track and Field. Other critics were less celebratory. “The American Pavilion with its stupid tank-treadmill outside and equally vacant political jokes inside is a national disgrace … the artists seemed to be trying to buy off anti-Americanism by turning the glib satire on themselves” (Jones). After the wow factor of the spectacle wore off, Saltz’s views on the works were far more disapproving, describing it as “one of the more obnoxious national acts ever executed at a Biennale.”5

Allora & Calzadilla, Track and Field, 2011. Installation view with runner Gary Morgan at the U.S. Pavilion, 54th International Art Exhibition. Photo: Tascha Horowitz.

One might also question the reasons why they didn’t directly address Puerto Rico’s political situation when given this golden opportunity. In light of their early political works, their projects for the U.S. Pavilion seem rather puzzling if not ambiguous. Instead of raising questions on nationalism and competition, it raises doubts and confusion, “why they performed on first-class American Airlines seats in carved and painted wood -Kirsty Bell argues- was rather mysterious, however, and seemed a somewhat labored attempt to conflate a nation’s promotional interfaces.”6 It might also be argued that a U.S. track and field athlete going nowhere fast on a treadmill atop an upturned military tank is suggestive of the state of much of the political art of today. If artists make works that are politically motivated, assuming they are committed to their social and political context, why aren’t they willing to push the envelope toward an explicit discursive criticality? This would create more meaningful experiences for viewers. If art is necessarily a means of communication, why privilege ambivalence?

It seems that disparate juxtapositions have become expected methodologies. This brings to mind The Camel’s Humps and the Ironing Board; a work that glues two strange objects together and tries to make sense of them ideologically by free association. Mostly a formal problem between support/pedestal and object, the camel’s humps can stand for “a monstrous wrinkle” (Apr. 2011). But it’s also symptomatic of the commodification of this type of art. Polish conceptual artist Jaroslaw Kozlowski once said: “I enjoyed arranging various conceptual configurations, combinations of more and more ingenious games and logical paradoxes. Again I felt the necessity to abandon that, get away from “stupefaction with form’” (Godfrey 275). It’s this ‘stupefaction’ that leads to a privileging of form over discourse, grandiosity over substance. And that’s perhaps one huge wrinkle that must be ironed out.

WORKS CITED

- Allora, Jennifer, and Guillermo Calzadilla. Interview by Carla Acevedo-Yates. Tape recording interview. Apr. 26, 2011, 3:00pm.

- Allora, Jennifer, and Guillermo Calzadilla. Interview by Carla Acevedo-Yates. E-mail interview. May 12, 2011.

- Benavides, Nadia. “Realidad y Ficción, Under Discussion, 2005.” Código 06140 Apr. - May. 2011: 97.

- Godfrey, Tony. “Decline or Diaspora in Conceptual Art?.” Conceptual art. London: Phaidon, 1998. 275.

- Jones, Jonathan. “Time flies at the Venice Biennale.” guardian.co.uk N.p., n.d. Web. 8 June 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2011/jun/07/time-venice-biennale-marclay-fischer?CMP=twt_gu>.

- Monge, José. Puerto Rico: the trials of the oldest colony in the world. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Pérez Rivera, Tatiana. “Gimnasia en la Bienal de Venecia” El Nuevo Día / elnuevodia.com N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2011. <http://www.elnuevodia.com/gimnasiaenlabienaldevenecia-905845.html>.

NOTES

1. See Alig, Lucie. “The Collaborator: Curator Lisa Freiman on Allora & Calzadilla’s Provocative U.S. Pavilion for the Venice Biennale” ARTINFO / ARTINFO.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 May 2011. <http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/35951/the-collaborator-curator-lisa-freiman-on-allora-calzadillas-provocative-us-pavilion-for-the-venice-biennale/>.

2. See “Allora & Calzadilla to Represent United States at 54th Venice Art Biennale.” U.S. Department of State. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 May 2011. <http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps>.

3. Allora, Jennifer, Guillermo Calzadilla, and Beatrix Ruf. Allora & Calzadilla. Zurich: JRP Ringier, 2009.

4. Saltz, Jerry. “Jerry Saltz on the Ugly American at the Venice Biennale — Vulture.” New York Magazine — NYC Guide to Restaurants, Fashion, Nightlife, Shopping, Politics, Movies. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 June 2011. <http://nymag.com/daily/entertainment/2011/06/jerry_saltz_on_the_ugly_americ.html>.

5. Saltz, Jerry. “Jerry Saltz’s Best and Worst of the Venice Biennale — Vulture.” New York Magazine — NYC Guide to Restaurants, Fashion, Nightlife, Shopping, Politics, Movies. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 June 2011.

<http://nymag.com/daily/entertainment/2011/06/jerrys_biennale.html#photo=8×00010>.

6. Bell, Kirsty. “International Pavilions” Art Agenda. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 June 2011. <http://www.art-agenda.com/reviews/international-pavilions/>.