« Features

Amplifying Your Collapse: Marco Fusinato in conversation with Emily Cormack

Marco Fusinato live at Bowery Ballroom NYC, March 2013. Photo: Greg Cristman | gregcphotography.com. All images are courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne & Sydney.

In the lead up to Marco Fusinato’s work being featured in “Soundings: A Contemporary Score,“ which runs from August 10th to November 3rd at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), Emily Cormack spoke with the artist, whose practice is equal parts violent subversion and conceptual seduction. Fusinato has been working as an artist and a noise musician for the past 20 years, refining a trajectory that draws on amplification, whether theoretical, physical or visual, to strip ideas and materials down to their essential properties.

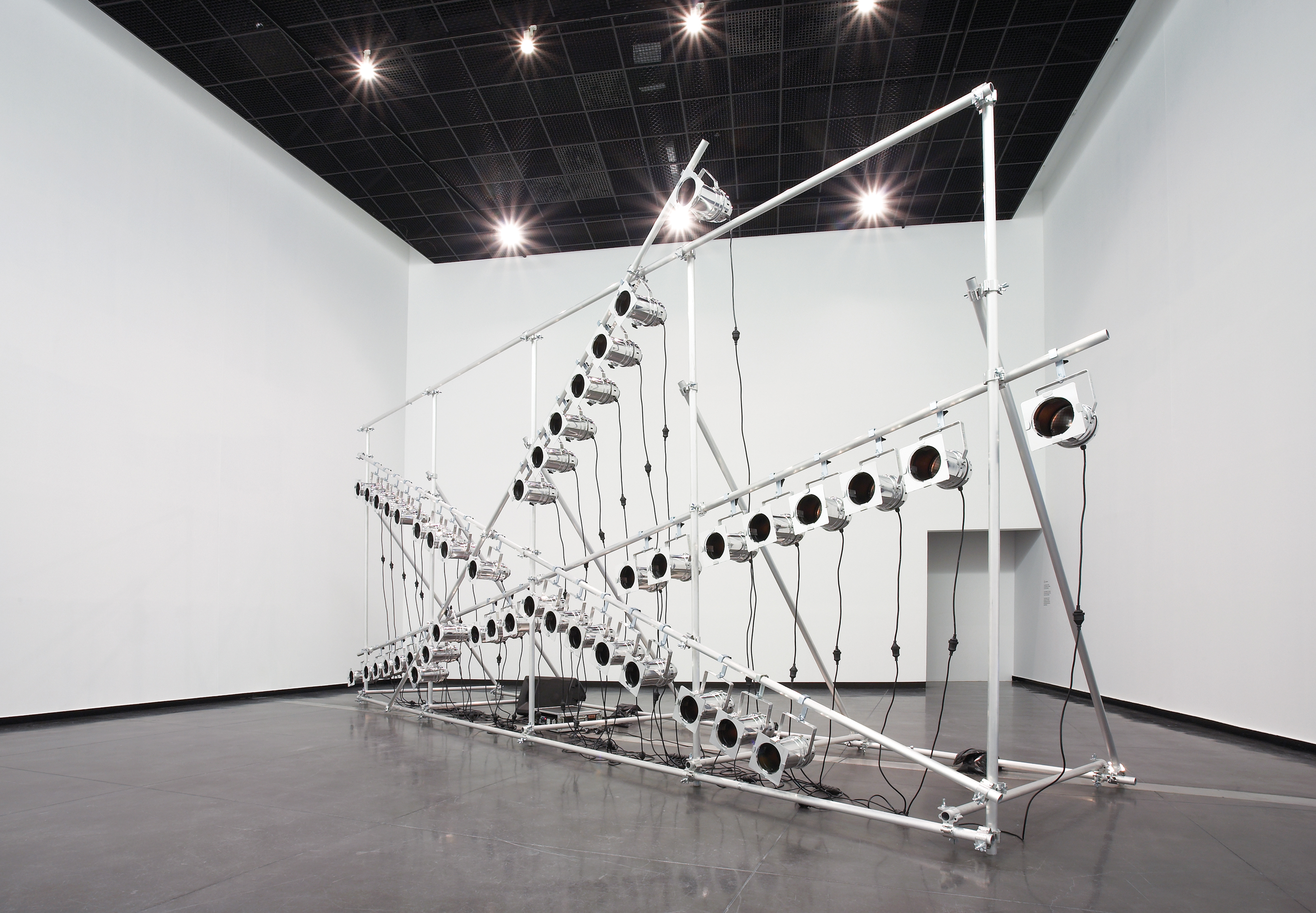

Emily Cormack - Clearly your work draws on anarchic and Marxist theories and ideas, and I want to understand the role that the audience plays in relation to activism in your work. In your 2009 work Aetheric Plexus and also in your recent work THERE IS NO AUTHORITY (2012), exhibited at Anna Schwartz Gallery in Sydney, the viewer is unwittingly implicated in the work. In Aetheric Plexus, first shown at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in Melbourne, the viewer is assaulted by a sensor-triggered barrage of 13,200 watts of white light and 105db of white noise; and in THERE IS NO AUTHORITY, the viewer is invited to walk upon a large rug woven with the words ‘There is no authority but yourself,” which is impossible to read while you’re standing on it. Here you seem to be enacting some kind of Brechtian activation device, in which you are attempting to compel the viewer to recognize their position and responsibility within a particular system. Can you talk about these ideas?

Marco Fusinato - The work Aetheric Plexus came out of various influences. In recent times the art institution, or more so the museum, has shifted from a place of contemplation to a place of entertainment, with amped-up marketing campaigns to make them popular destinations. The spectacle is fully integrated, as Debord predicted. With this in mind, I wanted to bring attention to the audience and make them central. Their gallery experience is usually physically passive as they walk around, quietly. My intention was to physically activate them-to make them aware of their part in, as you mention-the system. At the least, to realize they have a pulse and remind them that they’re alive.

Apart from working in gallery contexts I also play gigs in the experimental music underground. In doing so I am constantly surrounded by the infrastructure of these venues-the stage, the lights, the sound system and so on. The gear is there to highlight the performer, and no matter how fucked up it is there’s an expectation to ‘entertain.’ I had the idea to take that equipment and turn it on the audience-to highlight them and make them the spectacle. Their reaction is the work. The work THERE IS NO AUTHORITY uses another context shift. It represents a message of self-determination. The massive wool rug is a scaled-up reproduction of a black-and-white backdrop that the anarcho-punk band Crass performed in front of. The rug stretches right across the first third of the large gallery space. The audience is forced to walk on it as they enter the gallery. The woven text faces the back wall, and the audience is required to move around on the rug to view the whole plane to make out the text. No longer at the back of the stage, the text now is the stage. The audience is implicit in the message; ‘There is No Authority But Yourself.’ Thirty meters away at the other end of the gallery is a monitor mounted to the wall also facing the back of the gallery. It is connected to a hidden camera high above taking images every time someone walks onto the rug. By the time the viewer makes their way down to the end of the gallery and turns to see what is on the monitor they see their own image. They have been captured standing on the rug. Originally a simply painted mantra for anarchist ideals, it now takes the form of a fine wool rug in a commercial gallery. It’s these paradoxes relating to meaning and power that I expect the audience to question-at least in relation to their own position.

Marco Fusinato, Aetheric Plexus, 2009, Alloy tubing, Par can 56 lights, Double couplers, Lanbox LCM DMX controller, Dimmer rack, DMX mp3 player, Powered speaker, Sensor, Extension leads, Shot bags, 29’ x 13.5’ x 7.5’

E.C. - I wonder what your own position is on anarcho-punk as an ideology? Or anarchy more generally? In your exhibition “Noise and Capitalism” (2010) at Anna Schwartz Gallery, you used anarchist leaflets as your source material and screen-printed them in a manner that rendered them almost indecipherable. The activist vigor of these pamphlets was further numbed by their being presented framed behind glass and hung in a commercial gallery. Perhaps I am wrong, but I wonder if this is a statement about what you feel is the current position of anarchist ideologies and leftist movements as fetishized ideas, referents or products-rather than actual generators of thought or ways of being. The physicality of these pamphlets no longer has the revolutionary innuendo that they once did, but are instead enshrined behind glass. Can you talk a little bit about your intentions in using these political leaflets in Noise and Capitalism and your treatment of them in relation to your own position on these ideologies?

M.F. - The series Noise and Capitalism was based on my large collection of anarchist pamphlets. Many of my projects come from years of collecting material about specific interests I have. As a teenager, I was obsessed with punk music, especially the political side of it. It was through this I was introduced to forms of radical politics. Anarchism and all its offshoots I feel still have certain vitality and are necessary generators of ways to be in the world. There’s plenty of fractures within anarchist thought, from social to individualist classifications; however, there’s lots to be taken from the ideology, even on a simple level. How can you refuse the abolishment of oppressive governmental authority or the idea of free association of groups and individuals in a society based on voluntary cooperation? There are certain aspects that are inspiring, and this is evident in the writings not only in historical figures like Proudhon, Kropotkin or Goldman but right through to someone like Alfredo Bonanno, who I follow with interest. The concern is how does the ideology translate and how does the message not become a mess? That’s what I wanted to explore with the series. I noticed that the shorter pamphlets would sustain not only the argument but also my interest, while the longer ones would be difficult to grasp. I also wanted to take the pamphlet out from personal readership and present it in a public forum. I specifically chose anarchist pamphlets from the 21st century, first enlarging and then setting out each pamphlet as it once would have been laid out on the printing press. The upper-left quadrant contains the front and back covers; the upper right, the inside covers; the lower left, all those inside pages that would have been folded facing up, superimposed one upon the other; the lower right, all those that would have been folded facing down, also superimposed. So although the covers can be read clearly, the content pages of the longer writings become an ideological, illegible block of black ink.

E.C. - Can you perhaps talk a bit about the title Noise and Capitalism?

M.F. - The title came from a book released at the same time as making the series. It’s a collection of essays looking at the practices of noise and improvisation in relation to capitalism. It is a reflection not only on the artist/audience relationship, but also an investigation into whether this music offers resistance or fuel to capitalism. This is the field I work in. My ‘contribution’ to the discussion was this series.

E.C. - The gist of Mattin and Anthony Ile’s 2009 book does indeed seem to emulate the fine line that your work occupies between imminent rebellion/transgression and commercial appeal. While the ideas that you are speaking of might be Marxist, the channels that art and music have to publicize and demonstrate within are unavoidably striated with commerce. Is this what you mean by your contribution?

M.F. - I thought the title was an apt one in relation to the material I was presenting-anti-capitalist rants in a commercial environment. I think there are multiple layers to the reading of the series, and just like ‘noise’ it polarizes people. There are plenty of contradictions. I like that.

E.C. - To me, the series Noise and Capitalism is symbolic of these political and social ideologies-rather than actually anarchic in itself. Even in reproducing these pamphlets you are creating distance between the source material and the audience. This referencing of the material means that the works are signifiers of anarchy, rather than actually functioning to disrupt dominant power structures. In this way they become an academic, or almost archival, take on the development of these ideas in the current century. However, on the other hand, the inky, partial obscuring of these pamphlets reminds me of the slightly uncontrolled, rebellious nature of noise guitar, which you also have a strong practice in. As with noise guitar, where the givens of the instrument are transgressed and new sounds are discovered through encouraging unlikely collisions between technique and mechanics, is it possible that through placing these pamphlets within a commercial-gallery context you are setting up some kind of experiment about the insidious nature of rebellion? Just as feedback emits unexpectedly from a guitar and PA and penetrates space slyly yet persistently, so too might the radical politics contained in these pamphlets continue to be politically generative despite the staid, commercial appearance of these framed screen prints, enabling the ideologies therein to infiltrate surreptitiously into the homes of the bourgeoisie. Do you like this idea?

M.F. - I can’t control where these things end up. What I can do, however, is present ideas that hopefully encourage the audience’s desire to find out more-even if one person walks out of there and googles, ‘Bakunin, what the fuck?’-well then they are going to know more than before they saw the exhibition. I spend a lot of time researching each project, and often the idea requires production that I need to outsource. I choose materials that best articulate the idea and context. Much like when I play music, the guitars I use have a particular cachet. There’s a certain expectation that it would be played in a certain way. My point is to defy that expectation-to open up another realm on capitalism’s entertainment tool.

Marco Fusinato, THERE IS NO AUTHORITY, 2012, 100% New Zealand wool rug, monitor, camera, 30’ x 39’ Installation view at Anna Schwartz Gallery, Sydney. Lyon Housemuseum Collection.

E.C. - This reproduction of anarchic material or ideas reminds me of the distance that you create in another series of works, Double Infinitives (2009), first shown at Anna Schwartz Gallery. However, while Noise and Capitalism partially obscures the information that may lead to the transmission of radical ideas, Double Infinitives highlights a physically, direct, very clear and almost primal moment of transmission that is just about to occur. This series comprises larger-than-life, printed reproductions of protestors in the act of throwing stones set before bombed out cars and burning barricades. The figures represent isolated gestures of personal defiance depicting the moment when an individual takes up a collective cause with such passion and vigor that they are physically hurling objects at their oppressor. It is a desperate, primal, even Neanderthal gesture that to me actually reveals the protestor’s impotence. Throwing stones is surely a last resort in the possible armory of rebellion. Surely those powers that are successful in imposing rule do not enforce their authority by throwing stones. However, rather than Double Infinitives being a treatise of the inevitable, frustrated tragedy of this David-and-Goliath power struggle, these works do isolate a moment of violent, purposeful clarity and intensity and monumentalize it. Removed from the chaos of the moment and presented in isolation, the poignancy of this gesture is exemplified and reminds of the perpetual need for uprising and rebellion as an indicator of the health of human will. Instead of these works obscuring the meaning of the source material as with Noise and Capitalism, the works in Double Infinitives operate in a similar way as THERE IS NO AUTHORITY and Aetheric Plexus, in which the viewer is made aware of their responsibility for the state of things. The viewer occupies the point of view of the oppressor as the stone thrower hurls their missile in the viewer’s direction. Here again we are reminded of our passive positions within a political and social system where, despite our good intentions, we are always in some way oppressing or subjugating another. We are perpetually torn, conflicted and in contradiction with our intentions.

The title of this work, Double Infinitives, is a linguistic term that refers to a grammatical collision of conflicting tenses or modes. To me, it seems that these solo figures captured and stilled in their act of desperate rebellion embody the innate contradiction of contemporary existence, where we are so embedded within the systems of oppression that we are condemned to fruitless stone throwing at our invisible oppressors. Do you see these works as monumentalizing an act of genuine rebellion in an attempt to celebrate the purity and persistence of this act, or, as the title suggests, do you see these protestors as indicative of the innate inner conflicts of contemporary, conscious, anti-capitalist existence.

M.F. - Yes, the series is about questioning all the paradoxes you point out. For many years I had been collecting images of riots from magazines and newspapers every time an editor would publish that decisive moment when a rioter is wielding a rock in front of a fire. These images were collected from the time the millennium flipped up until I made the series in 2009-before the world exploded with events such as the Arab Spring and Occupy. I noticed that this image would occur consistently after most conflicts. My selection was specific. Each image is from a different part of the world, often years apart. Interestingly, all of the protagonists look the same: jeans, hoodie and their face covered. International style. Even the industrial production and presentation of these works is fraught with contradictions. They are made from the latest materials used in commercial applications. The black negative space being the raw material that the image didn’t cover. My intention of enlarging these images to history-painting scale was to emphasize this gesture that has been constant through history. Again, it raises a number of questions without providing answers.

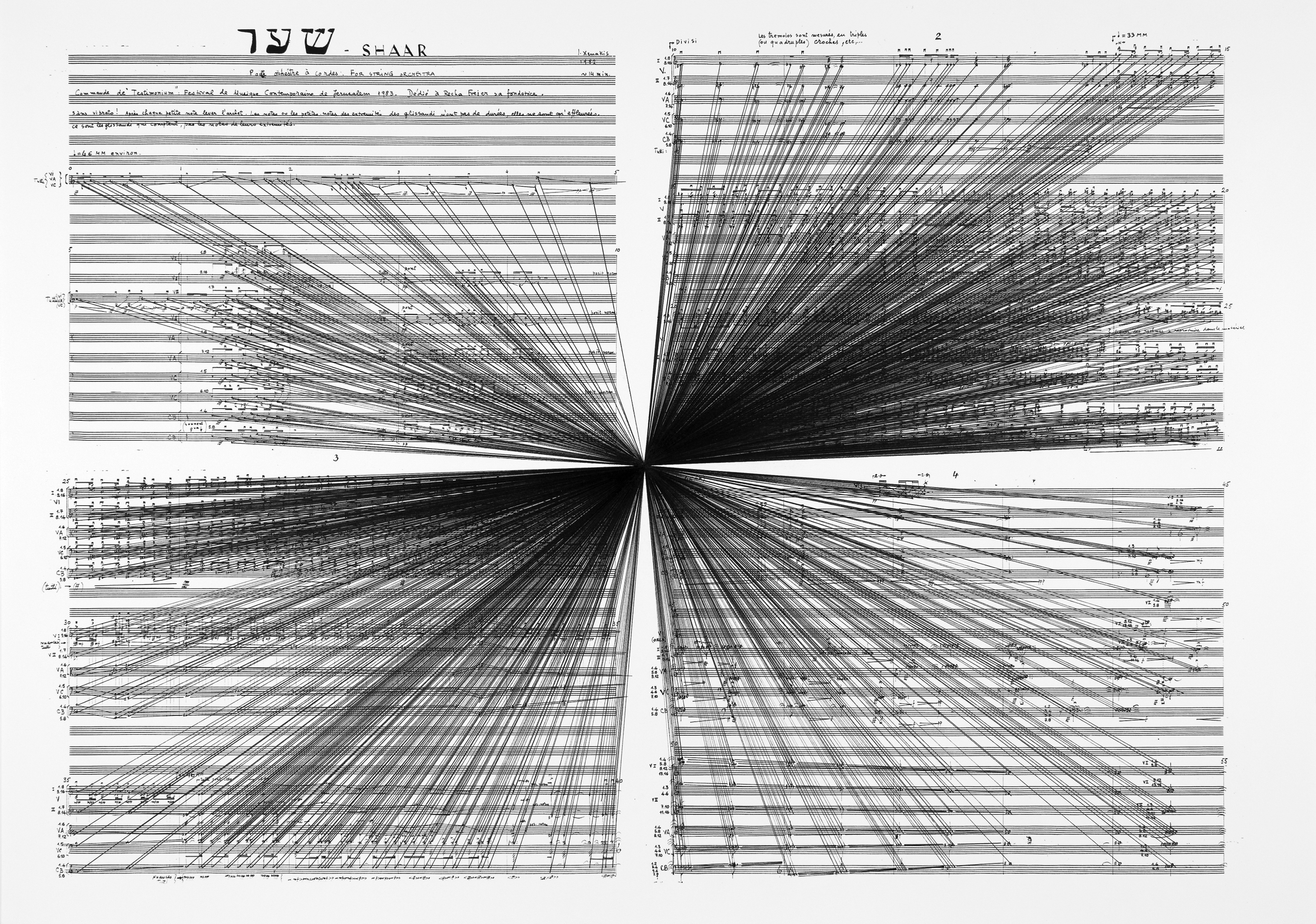

Marco Fusinato. Mass Black Implosion (Shaar, Iannis Xenakis), 2012, ink on archival facsimile of score, Part 1 of 5 parts, 32.3 x 43.1.″

E.C. - This reminds me of conversations we have had in the past about the role that amplification plays in your work. When I say amplification, I don’t mean physical volume, such as in Aetheric Plexus, but amplification through repetition, enlargement or amplification as seen in the pure, extremism of some of the 1970s-’80s Marxist-Leninist terrorist groups such as the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades), who I know have been an enduring interest of yours.

The ways that you process your material is to me a process of amplifying the essential elements of your sources down to a point of singular, blinding intensity-whether it is through layering a cacophony of Marxist pamphlets into a print version of reverb, or whether, as with Double Infinitives, a single act has been distilled so that it is emblematic of the paradoxes and collisions in contemporary existence, or, most interestingly, as with the ongoing series Mass Black Implosion (which is on exhibit as part of “Soundings: A Contemporary Score” at MoMA), where you actually converge an entire musical score to a single, randomly selected point. Perhaps using Mass Black Implosion as a starting point, can you describe whether you see a relationship between ideas of amplification and ideas of collapse, convergence and collision in your work?

M.F. - The scores for the series Mass Black Implosion are by avant-garde composers, ones known for attempting to extend the language of music-Cage, Xenakis, Cardew and so on. Each score is specifically chosen. They are significant contributions to the Western canon of ‘high’ music. My re-composition is a proposition for an intense noise piece. A complete collapse whereby every note is played at once. This re-imagining comes from my involvement and interest in noise as music. The original scores are some of the best examples of applied musical thought, and my template equalizes each one to a moment of singular impact. This idea of amplification/collapse is central to what I do. It’s a way of getting to the point in the most direct way. Everything becomes evident in the process. It’s a way of bringing everything down to its essence.

Emily Cormack is curator at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne. She has curated and co-curated major exhibitions in Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and South Korea. Emily writes frequently for artist’s catalogues and periodicals and is the Australasian reviewer for Frieze magazine, as well as a contributing writer for ArtAsiaPacific, Art and Australia and Kaleidoscope magazines.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.