« Features

Breaking the Medium of Painting Down

Interview with Sam Taylor-Wood

Sam Taylor-Wood’s films, videos and photographs unveil both the magic and the tragedy of the here and now. Beauty, immortality, art history and painting are some of the ingredients that characterize her remarkably intense oeuvre.

By Selene Wendt

Selene Wendt - In this exhibition the medium of painting is broken down and reshaped through the contemporary technology of film. How do you see what might be described as your painterly approach to film within this context?

Sam Taylor-Wood - With the piece that you have in the exhibition (A Little Death) it was about looking at things that historically have not changed. The importance of things that I have looked at through the years has not changed. A still life is still a still life, even in the transformation from painting to film. I am interested in ideas connected to mortality and the passage of time, as were the Dutch master painters

S.W. - This deep respect for aspects of art history and an understanding of it makes your work so compelling. Your works are constantly being compared to various artworks from art history. Surely this is the highest compliment?

S.T-W. - Yes, in fact it’s refreshing to be asked about the art historical aspects of my work, compared to the kinds of hellish questions that I am often exposed to such as: “What was it like casting Aaron Johnson?”, “What was it like working with Kristin Scott Thomas?”, or “What was it like working with a bowl of fruit?”

S.W. - Still Life is obviously one of your most iconic works in terms of the art historical references, and the link to Dutch vanitas painting is quite clear. As an art historian it’s particularly interesting to discover all the iconographical references in your work, and to unravel the various possible meanings. One of the aspects that I find particularly fascinating is how you capture, in the course of 4 and a half minutes on film, what the Dutch painters spent years trying to express in their painstakingly executed realist paintings.

S.T-W. - Well, of course that took me nowhere near as long as the Dutch masters took to paint their paintings, but it did take time to film and to work with it. I am interested in the art historical aspect, and then contemporizing it by including the disposable plastic pen, something that is so common from our society today, and kind of, well, not meaningless, but as set against something so classical and beautiful, it says something significant about the passage of time.

S.W. - I love the Bic pen! It’s incredible what a tremendous significance this small, unexpected detail has on the implications of the work. Still Life is the perfect expression of decay as a symbol of life and death. Only one year later you followed Still Life with a very similar work, which of course is a normal part of artistic development. Yet, as far as I know, you have not returned to this particular approach since. What are your thoughts about this?

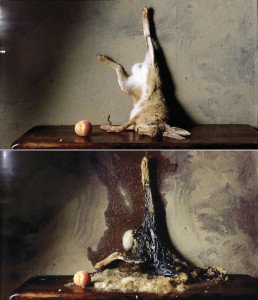

S.T-W. - I guess you could say that while the works are quite similar, with A Little Death I was looking at the subject matter from a completely different perspective. It was interesting in one way to take the idea one step further by bringing in an animal, and also, that animal specifically, the hare in history, is the symbol of life and virility as well. So it was sort of about looking at that and having the stillness of looking at that. I guess I didn’t quite know what to expect when I was filming it, and then when I put it in front of me as it were, so many things were surprising to me. One of the things I loved about it was how different it was from Still Life, but also made it come alive again. The deathly heavy scenario came to life again, and then it evolved into a sort of slasher horror film version of Still Life. A Little Death was more violent. Still Life conveyed a grace in the decay but with A Little Death it was not only violent, but shockingly violent. The feeling of the transformation of life into death repeating itself over and over is so frightful, and after those two works I sort of left the topic alone. I felt like I had achieved what I set out to convey.

One really disturbing aspect to me was the fact that the peach in the work was I guess a genetically modified peach. In six or seven weeks it didn’t even slightly rot. There was no sense of decay at all and that was quite disturbing.

S.W. - Yes, that is definitely an unsettling detail that relates to our contemporary society.

S.T-W. - Also, when I set out with a very clear motive and a clear image of what I want to do, and to then discover something completely unexpected, makes it even more interesting for me. This is similar to what happened with the pen. Initially, when I was filming Still Life I had someone overseeing it and they would go in every day to check the reels of the film and they took the pen out, thinking that I had left it in by mistake. So, having filmed for about six weeks, I had to start all over again! It was very annoying to say the least.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE PRESENT MOMENT

S.W. - One of the things I wanted to ask you about relates to Ossian Ward’s brilliant essay about your work. In discussing The Last Century (2005) he (paraphrases) Milan Kundera on Flaubert’s descriptions of the everyday, placing emphasis on the discovery of “the structure of the present moment; the perpetual coexistence of the banal and the dramatic that (underlies) our lives”. When I read that I thought, of course, this is what informs her work, but I am interested in knowing if you see this as a true source of inspiration for you, or simply an astute observation?

S.T-W. - This was absolutely brilliantly observed, but definitely also something that really does interest me. With a work like The Last Century, it was really about the freezing of a very simple moment in time, and just enjoying that moment, but also within that piece you can still see life continuing outside that moment. So it’s kind of like having parallel universes in the sense that these people are holding on to that time, suspended as it were, and yet you also see shadows of people walking past, you see a bus pull out and stop and I think the work, and these details are literally about those moments where you just want to stop and observe and look and feel and take time with that moment, which you can never really do in real life. And I suppose it is also an observation of the simplest of moments, not the grandest of moments. It’s about taking time to enjoy the banal moments that inform life.

Sam Taylor-Wood, A Little Death, 2002, 35mm film/DVD, duration: 4’. © the artist. Courtesy White Cube, London.

S.W. - In the process, you simultaneously pinpoint the beauty and the pain in the details of everyday life. Would you say you are more interested in creating magic out of the ordinary, or in unveiling the pain of human existence, or a little bit of both?

S.T-W. - I would like to say a little bit of both. I am definitely interested in unveiling the pain, but not in a way where you are looking at something so bleak and dark that it almost puts you on the outside of it. I like to look at things in the sort of simplest and most banal of moments, and for some reason you can feel the pain more if you are looking at the scene as a sort of an art piece instead of just observing what may be going on around you. Does that make sense?

S.W. - Yes, it makes perfect sense. This duality in your work is so intriguing, and it leads to another aspect that I find quite interesting. The small details that are hidden or taken away in your works captivate our attention and leave us wondering. The singer whose voice we cannot hear, the figure that casts no shadow, the cellist who has no instrument, the body that is seemingly suspended in space, the girl who cries with no visible tears, the bowl of fruit that decays within minutes all make us question what we are looking at, ultimately pulling us in and pushing us away at the same time. What exactly are you striving to convey in this unsettling give and take?

S.T.-W. - I’ve said this before, but sometimes I do feel that my work is three paces ahead of me in that I have a sense of where I am going with my work but at the same time I am not necessarily understanding what it is telling me, so when I am trying to figure out where to go with an artwork, I am really acting on instincts and lead by emotional thought and not necessarily conscious of why I am going in a particular direction. And it is sometimes not until I have gotten further away from it that I can actually see what I have been trying to achieve and think about it consciously.

S.W. - The exhibition title itself is kind of challenging. “When a Painting Moves…Something Must be Rotten!” I’ve been analyzing this and deconstructing it and trying to figure out exactly what it is inherently rotten in the movement of a painting, something which is not entirely unproblematic. How would you interpret this in relation to your work?

S.T-W. - I don’t know because inherently rotten I don’t feel that is exactly what I am thinking with my work. I am thinking much more that there is beauty in the rotten or there is a grace to the rotten more than that the rotten is a bad thing. Does that answer your question?

S.W. - Yes, it does, because really it’s almost a trick question. The exhibition title presupposes that you buy into the notion that something is not quite right when a painting is transformed to film, and yet that is the entire premise of the exhibition, to discuss the limitations of and possibilities associated with painting as interpreted by digital media.

S.T-W. - For me, as you look at this bowl of fruit, I feel that it becomes even more beautiful as it decays and as it goes into sort of nothingness. You still have the memory of the beauty and the grace of the passing of time I suppose. And it is also the fact that as you progress through life and you’re getting older and feeling the brutality of the passing of time, it’s nice to be looking at the gracefulness in that.

S.W. - I agree. Perhaps an even more compelling and relevant underlying theme is the notion of suspended time and how that is conveyed. Time is something that you spoke of earlier. In many of the works in this exhibition, this is typically conveyed through the use of highly controlled, steady and slow movement. Still Life and A Little Death involve the exact opposite approach - the speeding up of time. I find that contrast quite interesting. How does this relate to your views about life and death?

S.T-W. - I guess I have a quite astute sense of mortality having been through various bouts of illness. The speed at which these life threatening things can descend upon you, and how quickly you have to face your mortality is really quite shocking. The passage of time can become heightened and completely sped up when you feel that the finishing line is quite near. So I definitely feel that this relates specifically to my own personal perspective. I am interested in capturing a sense of graceful aging and the passage of time, and this is set against the violence of life and the swiftness with which things can happen. These are basically different approaches towards looking at the same thing.

Sam Taylor-Wood, Still Life, 2001, 35mm film/DVD, duration: 3’18’. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo: White Cube, London.

S.W. - As we also spoke about earlier, your approach to photography and film is quite painterly, so it is natural that your work is so often compared to and set up against masterpieces from art history. Are you in any way interested in addressing the status or relevance of painting today?

S.T-W. - I think the idea of looking at say a Caravaggio painting or another painting from one, two, or even three hundred years ago and seeing that artists are still dealing with exactly the same thought process and the same sort of questions - questions that generally come from the themes of our mortality and what it means to be human, or smaller themes such as the passing of time, or simple moments that are captured for eternity, these themes that evolve around life and love and death have obsessed artists from day one and I am equally obsessed with these themes. For me, referencing is a way of showing that through the centuries things really haven’t changed at all. We are still looking at and trying to figure out the same grand questions about our existence.

S.W. - I think that sums it up beautifully Sam. Thank you so much for taking the time for this interview.

* This interview was published on the occasion of the publication When a Painting Moves…Something Must be Rotten!, Selene Wendt and Paco Barragán (Editors). Milan: Edizione CHARTA, April 2011, pp. 36-40.