« Features

Darling Zackary

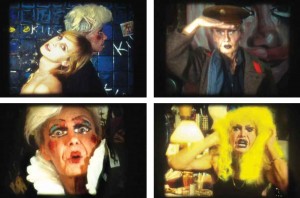

Zackary Drucker. The Inability to be Looked at the the Horror of Nothing to See, 2009-10, performance, Los Angeles, CA. All images are courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles.

By Tucker Neel

Zackary Drucker is a dynamo, who, at the young age of 29, has created an insightful body of films, photographs and performances challenging gender normativity. Her work, which always intersects with her own transsexual identity, postulates queer alternatives to the status quo. She has staged performances inviting audience members to perform depilatory actions on her body. She has created gorgeous and inquisitive photographs and films that document her life, her personality and image, but also interrogate larger questions of gendered performance, fashion, class, historical lineage, and bodies that resist codification. Recently she was invited to take part in the 2012 Hammer Biennial, presenting SHE GONE ROGUE, an opulent and fractured narrative film with existential leanings. In this interview she was kind enough to answer some questions about collaboration, language, family and her recent works.

Tucker Neel - Your most recent work is an experimental film titled SHE GONE ROGUE, which you made with director Rhys Ernst for the Made In LA 2012 Hammer Biennial. I know that the film features queer legends such as Vaginal Davis and Holly Woodlawn. Can you say a little about this film? What inspired it, and how do you see it relating to past work?

Zackary Drucker - Though the film is abstract and is situated in a fantasy/dream world, it is also autobiographical. I have relationships with all of the people in the film, whom, disparately assembled, represent my chosen family. All of the spaces we shot were on location, in the actor’s home’s, including my parent’s cottage in Crystal Lake, Pennsylvania, and the hundred-year-old house in Silverlake that Rhys and I live in. We also shot with Vaginal Davis in Berlin, Flawless Sabrina in New York City, Holly Woodlawn in Los Angeles, and there was an additional shoot in the Mojave Desert. Rhys and I were taking a break from our relationship, and he had moved out when the piece (that became SHE GONE ROGUE) started to form. I was alone in this house and the walls were literally falling down around me, the ancient plaster crumbling. I fixated on this for months, and it began to fuse with my psychological state-it somehow seemed symbolic or an actualization of my internal world. Rhys and I never actually split, and the film was made as a reconciliation of sorts; we wrote and produced it together. Over the year it took to make the film, he had moved back in, and it felt as though it was an afterlife of a relationship; restored, rebuilt, and we fixed the walls, too.

Zackary Drucker, You will Never Be a Woman. You Must Live the Rest of your Days Entirely as a Man and Will Only Grow More Masculine with Every Passing Year. There is no Way Out (still). In collaboration with Van Barnes, Mariah Garnett, and A.L. Steiner, 2008, digital video, color, 8:45.

My character, who is only ever referred to as ‘Darling,’ has a break with reality that leads her to her parents and archetypes, but as they may exist in the future or in a parallel dimension-reality as it’s reprocessed in dream state. It’s about so many things, and honestly is so fresh, I think we need some time and distance to adequately unpack what we did. Speaking for myself, I was thinking about how our bodies age and we go through time existing in any number of spaces and as constantly morphing forms. I think it’s also about mortality, about disappearing into one’s mind, about locating and reconciling my history (personal/cultural), while situating myself, now, within it. I think it’s a pretty deep Saturn Returns existential question mark-who am I, and how did I arrive here? Where am I going? What does my future look like? The people I look to in real life are the people I find in the film, even if their characters are, at times, nebulous and confounding, providing more questions than answers. It was exciting to have an excuse to make art with these brilliant performers and loved ones that I have always looked to as monuments of strength and perseverance.

T.N. - The film itself is quite beautiful, with decadent set decoration and some fantastic costuming. Did you style your actors, specifically Vaginal Davis and Flawless Sabrina, or was the construction of these characters more of a collaboration between you and these legendary performers?

Z.D. - There was a lot of collaboration involved with set design and costuming, but much of the aesthetic was already built-in to the character’s spaces and personas. Vag and Flawless’ apartments were pretty much left as is, though we brought select props into Flawless’ place-the altar, the wind-up toys, the record player, which we secured through one of Flawless’ friends. Flawless is her own brilliant stylist and always knows how to push the envelope with her look. Since Vaginal Davis was playing the Whoracle of Delphi, which called for more of a specific costume, my friend Marcus Pontello created her look for the television infomercial scenes. My friend Taylor Lorentz embellished Holly’s place for her scenes, and otherwise, Rhys and I filled in the gaps and made many of the decisions with art direction.

T.N. - One of my favorite recent works of yours was a doormat with your face on it emblazoned with the word ‘WELCOME.’ The work turns self-deprecation on its head, a kind of preemptive way of ‘throwing shade.’ I know you’re interested in the history of queer languages and that you’re inspired by the book The Queens’ Vernacular by Bruce Rodgers, which specifically addresses the art of reading. Your work often uses ‘reading’ as a device to talk about what is not talked about, especially in videos such as You Will Never, Ever Be A Woman…, in which you and Van Barnes trade loving chains of insults and a kind of Craigslist personal ad banter while lounging around in a domestic setting in various states of undress. I’ve always thought that the way you incorporate ‘reading’ into your work relates in some way to how the fine art world ‘reads’ work, with all the accompanying criticism, gossip and social accoutrements that inform the reception of artist and artwork. Does understanding the dialectics of insult and ‘reading’ ever influence how you see the art world, how you take or give criticism?

Z.D. - Absolutely. ‘Reading’ is about inoculating or preparing a person for a larger culture of intolerance. If we can articulate the most hurtful things we can imagine, then the words will have less power when being inflicted on us from the external world. It’s also a form of verbal self-defense; anyone who has been bullied or ostracized understands the power of words-it’s all we have to utilize in our uphill battle for self-respect, especially when your physical power or agency is constantly being compromised and dominated. I’m interested in The Queens’ Vernacular because it’s about identifying and putting names to things that didn’t have a name in the American lexicon-we’re talking between the 1920s and 1972 when the book was published. How do we understand our bodies, our genders, our desire, with the limited tools of language? We have to create a new language to define ourselves. I think of the possibilities of gender expression as color 3-D to hetero-normative culture’s black-and-white 1950s television set. All of these things are changing, and it’s up to those of us living in the future to define a new vision for the rest of society.

Zackary Drucker with Flawless Sabrina, At Least You Know You Exist, 2011, 16mm film transferred to digital medium, color, sound, 15 minutes.

T.N. - In your films and performances you establish a relationship with the spectator that confronts him with your gender, your sexuality and your body. In works such as The Inability To Be Looked At and the Horror of Nothing to See, the viewer is involved in the work and feels a variety of emotions that range from admiration, desire, judgment, to voyeuristic shame. Can you share with us how this resource challenges the viewer and impacts in the interpretation of your work?

Z.D. - My work in performance coincided with my decision to transition my gender from male to female. I started to become more aware of how often my body was being evaluated and scrutinized by the external world. I know this is consistent with a universal truth of being female, continually being seen and assessed, but there is something particularly awkward and vulnerable about going through puberty a second time as a fully formed adult, and towards a more visible gender at that. And eventually, the men who used to call you a faggot are suddenly licking their lips when you walk by, and women who were sympathetic become threatened or competitive. It takes a lot of energy to reconcile and overcome this inner voice that is constantly wondering if the people you come across in your daily life are reading you as a man, as a woman, as transgender, or as a non-person. If they are sympathetic, laughing at you, or shit-talking you in another language. The concept of ‘triple consciousness’ is at play here, and again, is not unique to gender so much as to any group of marginalized people who are visibly different than the dominant power group. Those works where I’m directly incriminating the viewer, their potential assumptions or judgements, are perhaps more of my own projection of what some of those voices of evaluation might sound like, as well as a verbalizing of my own internal process, an exorcizing of internalized shame, or self-doubt. There’s also a nod towards the relentless fetishizing of trans bodies, which is something of a subculture amongst a group of disenfranchised straight men; the underbelly of heterosexuality. The language of that particular style of sexual objectification seemed especially brutal and without boundaries. Performing, for me, is also about collectivity, about tapping into the truth that we are all trapped in bodies that we didn’t choose, and nobody makes it out alive.

Zackary Drucker, You will Never Be a Woman. You Must Live the Rest of your Days Entirely as a Man and Will Only Grow More Masculine with Every Passing Year. There is no Way Out (stills). In collaboration with Van Barnes, Mariah Garnett, and A.L. Steiner, 2008, digital video, color, 8:45.

T.N. - Last February, you participated in the symposium Shares and Stakeholders as part of The Feminist Art Project 2012 conference. You participated in a panel titled “Destabilizing a Destabilized Existence” with A.L. Steiner. As the promotional materials for this panel stated, through this discussion ‘you reflected on “outsider” identities, and how potential future without gender binaries could situate feminism into uncharted territory.’ Can you share with us your thoughts about this discussion?

Z.D. - Steiner and I always have a really fun and productive time when we join forces. We took the opportunity to share our histories as feminists and aligning our identification as feminists within a larger goal to obliterate the gender binary system, which though a radical idea, is what we should all be aiming for. Patriarchy, sexism, heterosexism, transphobia, couldn’t exist without a binary. One group is always on top if there is a clear delineation between two categories of people, and quite honestly, it doesn’t serve any of us very effectively, straight cisgender men included. As our definitions expand of what men and women are, we should strive for a more inclusive politic where nobody is defined by the genitals they are born with, how they decide to use or who they share them with. This is what the future looks like.

Zackary Drucker, Distance is Where the Heart is, Home is Where You Hang Your Heart, # 5, 2011. In collaboration with Amos Mac, digital C-print.

T.N. - For many trans-identifying people the concept of family and home can be a troubling or frustrating thing, with parents often not understanding the complexity of gender and identity. Many parents end up being outwardly hostile towards their trans children. You returned to your childhood home to work on the recent show at Luis De Jesus. Your parents are in your upcoming video for the Hammer Biennial. How has having supportive parents impacted your work, and what thoughts do you have about the notion of family, both drag and trans families and biological families?

Z.D. - I am incredibly fortunate. My parents are my role models, and I believe that they are role models of good parenting, which is one of the primary reasons I include them in my work. The world needs to see that there is an alternative to parents rejecting and marginalizing their transgender children. The child-parent relationship is so much about reciprocal learning, and I think I’ve taught them as much as they’ve taught me. They never took a strict authoritarian position with me, so I think they have a less-defined sense of hierarchy and have always been open to learning. No parents are free of expectations or dreams of who their children may become. I’m sure it takes a lot of adjustment to reconcile who your children become as adults, but I think it’s narcissistic to expect your children to reproduce your projection, or align with your ideology and values. Above all, my parents are invested in my happiness, and they realize that it took me becoming an artist, a woman, a Californian, etc., to get there. I’m fortunate because they are progressive-minded and educated, and in most ways I am a pretty direct descendent of their ideals. Millennium version. Many parents are probably too invested in their own antiquated values to accept their children’s autonomy, but mine are cool, and they’re fun to be around too.

The confidence my parents’ support has given me has been really instrumental in enabling me to present myself as a subject/object without feeling shamed or disempowered as a trans person. And some of it comes from my ancestors I’m sure, and queens, and trans people, past and future. As queers, we’re lucky to have the advantage of assembling a chosen family too, which has been crucial to my development and my manifestation of self. (Aunt) Holly, (Mom) Vag, (Dad) Ron Athey, (Grandma) Flawless and my (Sister) Van-and that’s just a start, as I have a handful of other siblings-have all been incredibly influential and powerful figures in my life.

T.N. - You are extremely busy these days, gearing up for more museum exhibitions. Can you talk a little about what you have planned for future work?

Z.D. - My last film, At Least You Know You Exist, will be installed for the duration of the summer at both the Moscow International Biennale for Young Art and MOMA’s PS1 in New York. It is also screening at the Hammer Museum, alongside Flawless Sabrina’s 1968 film The Queen and Holly Woodlawn’s 1972 black-and-white silent film, Broken Goddess. That’s on Wednesday, August 22nd, in the Billy Wilder Theater, and all three of us will have a conversation following the screening. I can’t wait for that. Holly and Flawless love each other dearly, and together they are explosive and magical and like two timeless children. I’ve got a few things up my sleeve following those shows, but I’d rather surprise you with them in the near future.