« Reviews

Federico Uribe: Painting on a Shoestring

Now Contemporary Art - Miami

Transforming Found Objects into Transformative Art

By Elisa Turner

For this artist, enough is almost never enough.

Federico Uribe plays with an impressively wide palette of colors and forms, primarily materials plucked from the clutter of daily life in the late 20th century and early 21st century. This mind-boggling plethora of purely mass-produced “stuff” is a far cry from sleek readymades Marcel Duchamp made famous decades ago when the 20th century was new.

As Uribe explains, “As much as I can, I try to respect the materials the way they are and try not to change the conditions they come with. They have their own beauty, and I have to respect that.”

For sure, Andy Warhol’s Pop Art sensibility figures broadly in Uribe’s art, which is partly inspired by objects and tools many of us need to move forward in daily life, objects often simply called ‘found objects.’ Sometimes, however, it seems that Uribe’s art, a curious hybrid of painting and sculpture, is fashioned not so much from objects he has found but from objects that find him.

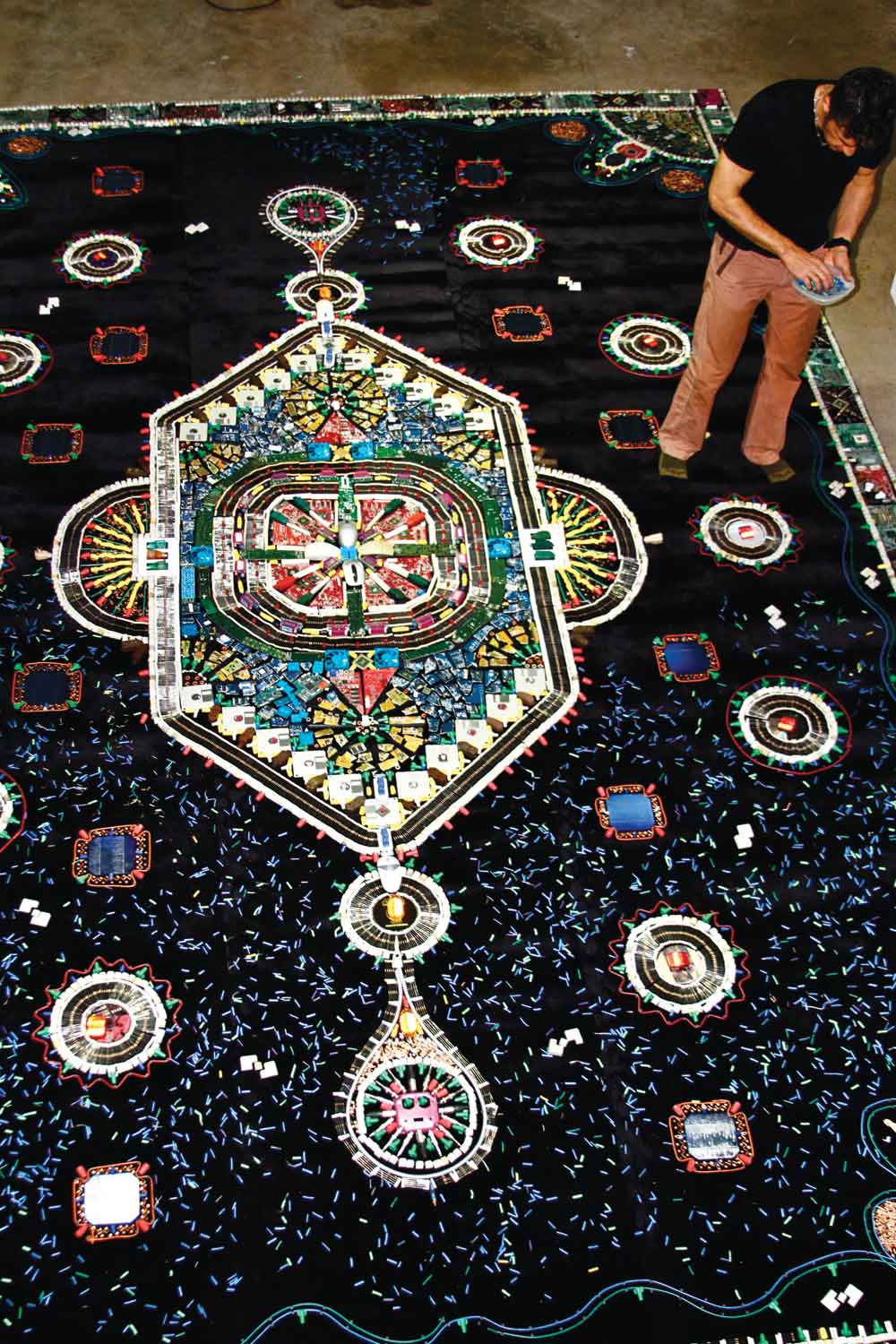

Federico Uribe working on Supported by Technology, 2012, wires and computer parts, 11’ x 16’. All images are courtesy of Now Contemporary.

Recently, Uribe visited his exhibit, “Painting on a Shoestring,” at Now Contemporary Art gallery in Miami’s Wynwood district to talk about the arresting materials and meaning of his latest works on view there.

So, why has he used so many found objects over the years? Uribe-whose current résumé lists international solo and group exhibits dating back to 1999, with shows in Spain, Italy, Mexico, New York and Miami, where he now maintains his studio-laughs a bit before he explains: “I work with found objects because I am attracted to them. I choose them because of the plastic possibilities.” As far as a particular object like a plastic baby-bottle nipple or a shoelace, “I don’t see it for what it is. I see it for what it looks like.”

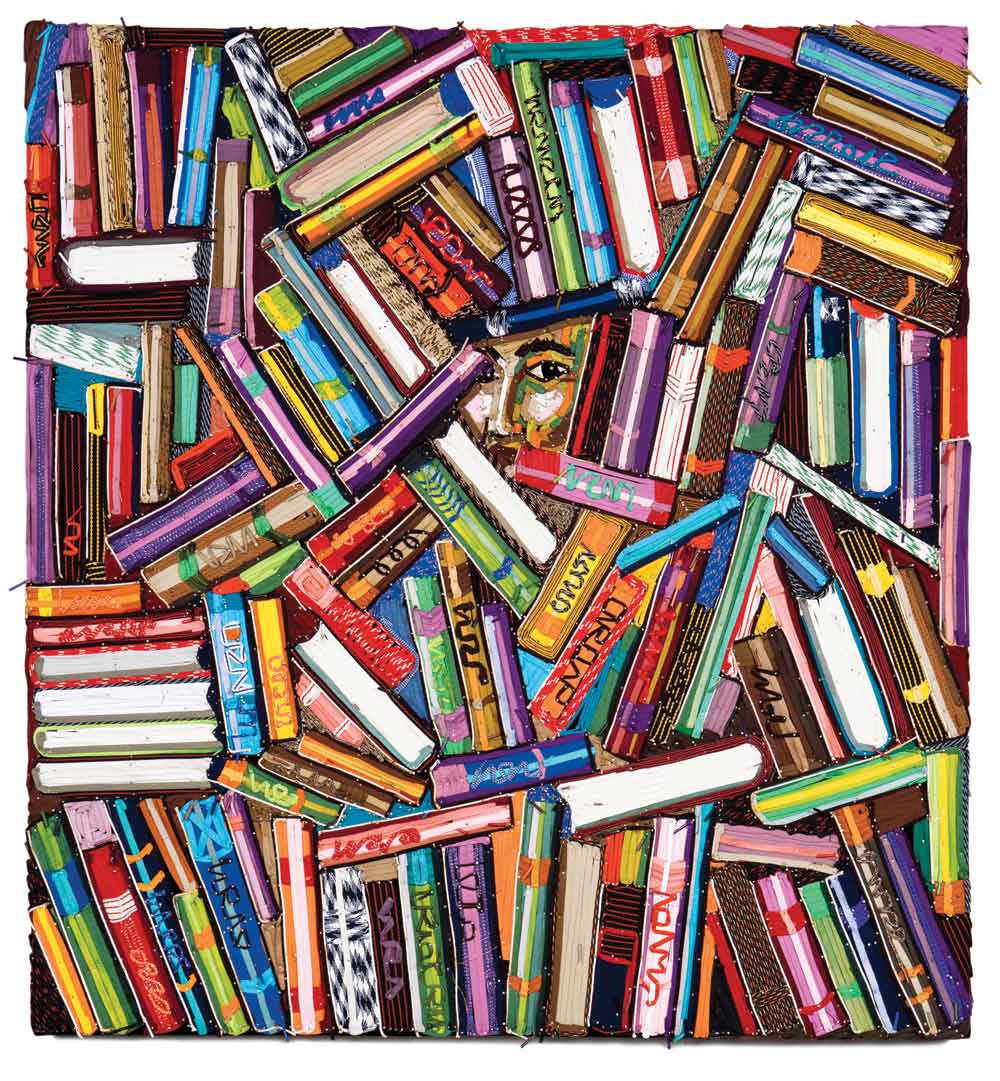

“I have worked with all sorts of objects,” Uribe continues. “I work with pencils a lot-it is not a found object, but it is an object. I have worked with shoelaces, shoes, baby-bottle nipples, screws, gardening tools, computer keys, coins, anything that comes my way that I can work with. People give them to me for whatever reason. Most of these come to my studio by chance.”

Initially trained as a painter, having studied art in his native country of Colombia and later in New York, Uribe decided to abandon painting in 1996. His creative curiosity led him to other materials that could carry for him some of the emotional and formal resonance of paint, and yet still remain evocative of their past life and purpose as humble, utilitarian objects. He began to collect all sorts of these objects, combining them in unexpected ways.

Many of the 14 artworks in his current show at Now Contemporary Art incorporate paint-box-colored bits and coils of electrical wire. In certain works, from a distance, they look almost as if they are bright, flat strokes of paint. “This is all wire I got from friends of friends,” he explains. Implicit in these materials, now transformed into art, are echoes of their intensely pragmatic, workaday origins. Some wire came from an electrician who works on Uribe’s studio, another from a client of the gallery who has a music studio.

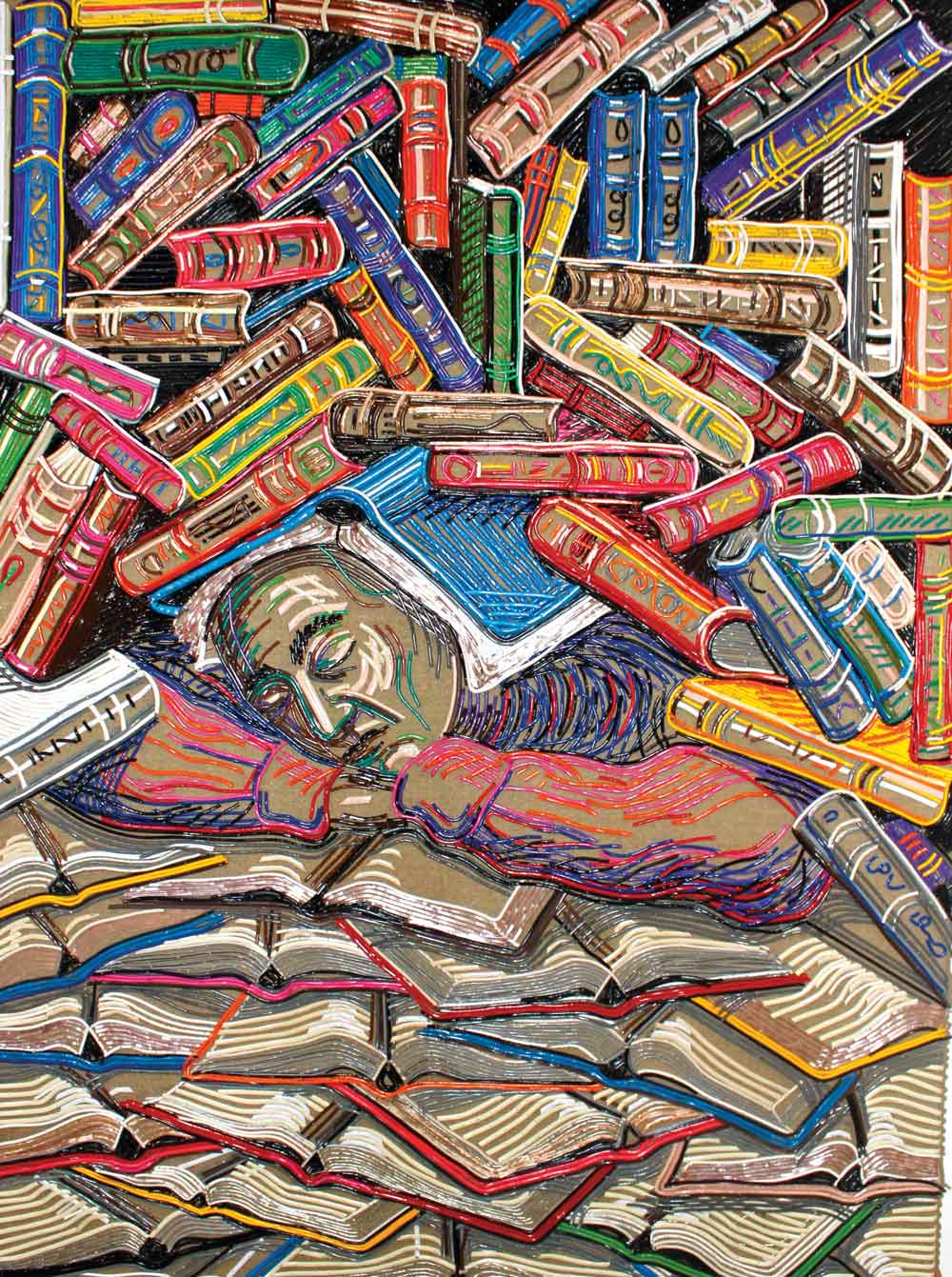

Yet the artist’s painterly sensibility remains paramount in the current show at Now Contemporary Art. Clearly, he is an accomplished, at times exuberant, colorist. Looking at these works from a distance, a near-sighted viewer could be forgiven for thinking that Uribe’s “paintings without paint,” as they could be described, are indeed painted canvases possessing subtle echoes of figurative paintings by such artists as Alice Neel, Wayne Thiebaud and Philip Pearlstein.

For somewhat earlier works, an arsenal of crisply sharpened colored pencils, held together with plastic fasteners, was transformed into a dynamic series of figurative sculptures, “Pencilism,” in 2009. This series is yet another example of how Uribe, as he has done in the current exhibit “Painting on a Shoestring,” gracefully balances a poetic line in his art. This line connects the act of making painting and sculpture with collecting and sorting leftovers gleaned from the mass-produced clutter of stuff infiltrating our daily lives 24/7.

The title of this series, “Pencilism,” cleverly recalls the name of a movement in art history, pointillism. Although examples of this technique, combined with various approaches, can be found as far back in art history as the Renaissance, pointillism itself was pioneered by Neo-Impressionists, particularly by French painter Georges Seurat (1859-91). When viewed up close, similar to famed Impressionist canvases, pointillist paintings seem to be an undifferentiated mass of colored dots, surely anticipating wholly abstract paintings. When viewers step back, the colors blur together so that what is being depicted on the canvas can be comprehended correctly. Uribe has used pencils to create both figurative and abstract imagery, including the luminous spherical work Spiral of 2009.

“I like the idea that I have this echo somehow of the history of painting,” says Uribe. “Because it’s pretentious to think that you don’t have a relationship to art history.” Surely speaking about many serious contemporary artists dedicated to refining their work, he adds, “You are not making it up. You are just doing it in your own voice, hopefully. You cannot avoid being part of this tradition.”

In the current exhibit at Now Contemporary Art, there’s a riveting work that brings to mind the visceral boldness and vulnerability of painted self-portraits by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). In both Kahlo’s The Two Fridas (1939) and Uribe’s Conectado con el Corazón, we see a figure’s chest exposed to reveal the heart inside. Kahlo’s work is actually a double self-portrait, with her heart exposed in each case. Granted, there are many significant differences between the two works, not the least of which is that Uribe has created a cleverly articulated image with multicolored electrical wires. Moreover, his image shows just part of the face and is intensely focused on an androgynous figure ripping apart his or her chest to reveal a blood-red tangle of wires exploding outward. Red electrical wires, capped by metal “plug-ins,” seem to be flying in almost every direction to seek connections that will, perhaps, generate new life in an ailing heart-or, at least, a heart needing human connections to thrive.

Like Kahlo, Uribe is drawn to self-portraiture, although he no longer uses the medium of paint. But he clearly thinks like a Kahlo-esque painter. Looking around this exhibit, he says, with a slight laugh, “These are mostly psychological portraits of me. They don’t look like me exactly, but they are portraits expressing concepts….[each] is an image that is translated feeling.” About Conectado con el Corazón specifically, he says, “It’s the feeling of being open to meet people, to relationships, so there is all this wiring from your heart that you extend out to meet people.”

Often these provocative works evoke a subtle theme of violence, surely in synch with many of Kahlo’s most important and memorable paintings. For all of Uribe’s painterly skill for rendering the human figure in Brain Wash, Dilemma, I‘ve Been Thinking and Eating Chicken, these works do suggest a painstaking if not painful attack on the canvas or surface, and by extension, on the figure itself being portrayed. They are produced by lining up and twisting back on themselves endless amounts of colored shoelaces, which are then precisely pinned in place. Each image glitters with many tiny heads of metal pins.

“This is all thousands and thousands of straight pins,” he says of one such work incorporating shoelaces. “They are not glued. They are pinned. The pin itself, it hurts.” He notes that he used a similar approach to create Romantico, which shows two hands holding a riotous bouquet of flowers. It’s constructed with electrical wires nailed in place.

“There’s implied violence in everything I do, somehow,” Uribe says. “Because the way I choose to build stuff is somehow cathartic of some rage.” It’s possible to see in his Picasso-esque rendering of hands holding flowers the sense that he is being violent to the flowers by nailing these bristling, flower-like fragments of wires in place. Why would that be cathartic?

“I grew up in a country of war. I suppose, in some part of my heart, I am an angry man,” Uribe confesses. “I guess I am peaceful because I do this.” Making art from ordinary and unsung objects found in daily life, he adds, is a way he can refocus his anger instead of engaging in murderous violence.

And why not? Looking at art that transforms familiar, found objects could help us perceive our own surroundings in new ways, rather than resorting to same-old, same-old disputes.

For citizens hoping to end their country’s distant wars, bridge a divided electorate and heal damaged coastlines, encountering transformative art might be a remarkable start. If, of course, we’re lucky, and the “art gods” smile on us.

(November 9 - December 31, 2012)

Elisa Turner teaches at Miami Dade College and is Miami correspondent for ARTnews. She has written for Arte al Día, Art+Auction, ArtReview and The Miami Herald.

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.