« Features

Figurative Drawing: E. H. Gombrich and Stephen Wiltshire, “The Human Camera”

It is not my intent in this short essay to conduct an in-depth critique of E.H. Gombrich’s masterful work in the psychology of perception and its relation to figurative drawing. His book Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation is justifiably famous. Rather, my goal is to review some of Gombrich’s main conceptual points and apply them to the incredible drawing abilities of Stephen Wiltshire (as can be reviewed in any number of YouTube videos).

Briefly, Wiltshire has been called “the human camera” because of his skill in rendering the exact architectural details of various cities over which he has been flown (Rome, London, Tokyo and others). Upon returning to his studio, he proceeds straightaway to sketch complex, virtually trompe l’oeil drawings from memory without the use of notes, sketches or photographs. Oliver Sacks, the famed neurologist, was good friends with Wiltshire and recognized in him the unique abilities of a high-functioning autistic savant whose photographic memory gave him very special skills in drawing and music. It is important for my purposes to note that Wiltshire had no educational or artistic training when he first produced his hyper-realistic drawings at a very early age.

In The Sense of Order, Gombrich summarizes his position on how representation works in art:

In Art and Illusion I have tried to show ‘why art has a history’ and I gave psychological reasons for the fact that the rendering of nature cannot be achieved by an untutored individual, however gifted, without the support of a tradition. I found the reasons in the psychology of perception, which explains why we cannot simply ‘transcribe’ what we see and have to resort to methods of trial and error in the slow process of ‘making and matching,’ and ‘schema and correction.’ Given the aim of creating a convincing picture of reality, this is the way the arts will ‘evolve (1).’

Ernst H. Gombrich. Art and Illusion, A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. 6th Edition. Phaidon Press, 2004.

In this revealing passage, Gombrich is claiming, in effect, that there is no such thing as an “innocent eye.” (John Ruskin) Artists do not paint what they see; they see what they paint by means of complex cultural and historical schemata or perceptual sets that are learned consciously or subconsciously in much the same way that written and spoken languages are learned. Beholders of representational works operate by means of similar schemata, which are culturally induced ways of seeing. (John Berger). Gradually, says Gombrich, artistic techniques, such as perspective, are developed by trial and error and compared (asymptotically, I should imagine) to the natural world and, correspondingly, audiences come to accept new ways of understanding the depiction of natural phenomena.

Gombrich’s general viewpoint was highly influenced by, among others, the British philosopher of science, Karl Popper, who basically argued-as Thomas Kuhn did later-that there are no “theory-neutral observations” of natural phenomena, especially in regard to deriving and testing scientific theories. That is, perceptions are inevitably and completely influenced by one’s theoretic or schematic expectations of what one assumes is there to be experienced in nature. Popper once notoriously stressed this point by stating “Observe!” to a class of students who remained wholly in the dark until they were told what to observe and why. Readers of this essay, of course, will see in Gombrich’s position a kind of early prototype of “reader-based” semiotics commonly found in many post-structuralist theorists (Derrida, Barth, Foucault, et. al.), where heavy stress is placed upon the lecteur (and to a somewhat lesser extent the auteur) and his/her intertextual fields of meaning.

But now, enter Stephen Wiltshire. He and his sister have both claimed that Stephen spontaneously started drawing hyper-realistic buildings, cars, and people at a very early age without benefit of any training or education in art. It is tempting to see this as an immediate falsifier of Gombrich’s claim that “the rendering of nature cannot be achieved by an untutored individual, however gifted, without the support of a tradition.” Of course, there do seem to be some significant differences in the autistic brain and how it processes information. This is apparently undeniable and clearly places Wiltshire and others like him in a special category of achievement. Thus, it would be possible for a defender of Gombrich to argue that these cases are “outliers” and that they do not represent the vast majority of standard cases in which Gombrich’s claim holds true. Naturally, this reply is plausible, but the issue of representational art and the psychology of perception is complex.

I would like to point out initially that, after 28 years of teaching at the Savannah College of Art and Design (philosophy courses, not studio art), I’ve known many students who claimed that they entered foundation classes with no appreciable ability to draw representationally and that subsequently through various trial and error courses, such as Drawing and Color Theory, they became reasonably competent. This phenomenon supports Gombrich’s position and also that of Betty Edwards in Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. However, this is hardly the whole story. I have also known any number of students who said that they started drawing realistic images at a very early age with no art instruction at all. So, the reviews have been mixed. This suggests that Stephen Wiltshire’s ability is a very special instance of what is not so uncommonly found in the general population of artists. The difference may be one of degree, not one of kind.

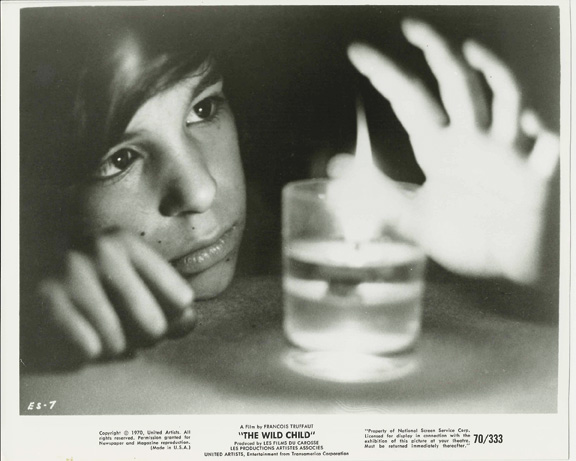

The Wild Child (1970), directed by François Truffaut and produced by Les Films du Carrosse, tells the story of a child who spends the first eleven or twelve years of his life with little or no human contact. The film is based on the true events regarding the child Victor of Aveyron. The American psychologist Harlan Lane wrote a famous book about him.

Secondly, Gombrich’s general view on the crucial importance of schemata in the psychology of perception and representational art may commit an odd kind of mistake in reasoning that can also be found, I believe, in many of the post-structuralists and their claim that language games (Wittgenstein’s sprachspiele) constitute and “frame” what counts as “reality.” In this they are following Saussure’s assertion that language does not derive its meanings by referring to the external world, but by referring to the open system of broad intertextual uses and contexts. Thus, in effect, humans are surrounded by the “bubble” of language, and this bubble, with all its attendant intertexts, perceptual sets, cultural and historical schemata, and other such intermediaries, shapes what will count as reality and how we perceive it. I note in passing here that, in a way analogous to the post-structuralists, Gombrich claims that the process of artistic “making and matching” begins with a number of drawing techniques or schemata that are then compared to represented items in the external world, and that gradually a more appropriate “fit” develops and is eventually accepted as a more integrated cultural way of seeing.

But if the human eye is never “innocent,” schemata would always be compared to other schemata; there would never be the possibility of an exact match with the external world or even that of an asymptotic approximation. The conceptual trap for Gombrich is clear: either he is committed to the view of an endless succession of artistic schemata with no real interface with external reality or at some point artists and beholders “simply see” that advanced schemata really do capture how items in the external world actually look. The latter position is self-referentially inconsistent for Gombrich, while the former leads to an infinite regress of schemata.

Without venturing too far afield, I would like to suggest that the root of Gombrich’s claim about the psychology of artistic representation, which is similar in a way to Kuhn’s view about paradigm shifts in science, comes from what philosophers of mind categorize as “idealism” or “indirect realism”; namely, the claim that humans do not and cannot have direct, non-inferential perceptual access to the external world. This claim has a long history, dating back to Descartes and especially Kant. I cannot, of course, expand on all this in a short essay, but it is worth noting that a number of contemporary philosophers have been ardent defenders of “direct realism,” which maintains that, in perceiving the external world, we do not have direct, non-inferential access to things such as “sense data” that supposedly mediate reality to us, but rather we have direct perceptual access to properties of things themselves in the external world (2). If direct realism is defensible, it seems to constitute something akin to a falsifier of the epistemological basis of Gombrich’s Art and Illusion, or at the very least a fascinating alternative account of how representational art might work in terms of direct resemblance of things in nature.

In closing, I would like to propose a thought experiment. Consider the actual case of a young boy of about 12, subsequently given the name Victor, who was discovered roaming in the wild in the south of France in the early 1800s. The American psychologist Harlan Lane wrote a famous book about him entitled The Wild Boy of Aveyron (3). Victor could not speak a language, and he was utterly unable to demonstrate any “normal” range of so-called “civilized” social behaviors. Harlan suggests that Victor was not mentally deficient, but that he had missed the crucial windows to acquire many important social skills, including language. What I would like to imagine is the following: suppose Victor had been presented with a very accurate line drawing of a tree in his earlier environment with which he had an intimate acquaintance. Would he be able immediately to see the resemblance between the drawing and the tree? Is there any reason to suppose he could not? Direct recognition of the similarity between representational depictions and their represented items in nature (as is suggested in the case of the caves of Lascaux and Chauvet) would undoubtedly have had important survival value for early humans. This is notwithstanding the American philosopher Nelson Goodman’s claim that pictures resemble nothing more so than other pictures. Like Gombrich (although with greater elaboration), Goodman argued that we humans have to master how to “read” the symbolic systems of visual languages in approximately the same way we learn how to read the symbolic systems of written languages. Goodman believed that it is impossible to have a natural perceptual match between representational drawings and their models in nature, but this utterly conventionalist view of representational art has certainly been put to a real test by the beautiful enigma of Stephen Wiltshire, the human camera.

Notes

1. E.H. Gombrich, The Sense of Order. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1979, p. 210.

2. For a spirited defense of direct realism, see Michael Huemer, Skepticism and the Veil of Perception. New York, N.Y.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.

3. Harlan Lane, The Wild Boy of Aveyron. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976. François Truffaut’s movie The Wild Child (1970) is also based on the life of Victor.

John Valentine is a professor of philosophy at the Savannah College of Art and Design, where he has taught since 1990. His publication credits include the textbook Beginning Aesthetics (McGraw-Hill, 2007); articles in the Florida Philosophical Review, the Southwest Philosophy Review, the Journal of Philosophical Research, the Journal of Speculative Philosophy and The Philosopher; poetry published in various journals, including the Sewanee Review, Midwest Quarterly and Southern Poetry Review; and six chapbooks of poetry.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.