« Feature

I Think Art Is a Way of Intensity. Interview with Hermann Nitsch

One of the founders of the radical art movement Viennese Actionism in the 1960s, Hermann Nitsch is widely known for his actions and paintings created for his ritualistic Theater of Orgies and Mysteries. Now 78, the Austrian artist has created thousands of artworks during hundreds of performances over his very active career. He recently took a moment out of his busy schedule to discuss his controversial art with ARTPULSE from his castle outside of Vienna.

One of the founders of the radical art movement Viennese Actionism in the 1960s, Hermann Nitsch is widely known for his actions and paintings created for his ritualistic Theater of Orgies and Mysteries. Now 78, the Austrian artist has created thousands of artworks during hundreds of performances over his very active career. He recently took a moment out of his busy schedule to discuss his controversial art with ARTPULSE from his castle outside of Vienna.

By Paul Laster

Paul Laster - How did you come up with the idea for your Aktionens [Actions] and the Orgien Mysterien Theater [Theater of Orgies and Mysteries]?

Hermann Nitsch - It was a long time ago. I would say 1958, when I was very involved with music and theater in Zurich, and I tried to develop a new kind of Gesamkunstwerk [a total work of art]. I was very influenced by Wagner and Scriabin. It was very important to me to not make a classic form of theater. It was important to not use a classic form of poetry. I didn’t want the audience to have to use words, rather I wanted them to use their senses. It was important that they directly engage smells, tastes, touch and to see and hear. What I did was very close to happenings and performance. I wanted to develop real events, real happenings, and so I began my theater to create these kinds of actions.

P.L. - What’s the philosophical point of view related to the actions?

H.N. - I wanted intensity. That was very, very important. I wanted to use the senses very intensively. In my life I was a pupil of Nietzsche. I wanted to create a perception of life and being in my theater with a new intensity.

P.L. - What’s the purpose of using blood and animal parts in your performances?

H.N. - I spoke about the senses. Blood is part of our body. Meat is part of our body. I wanted to explore the conditions of life. It’s a problem of intensity-to see and to feel blood and to touch meat and intestines.

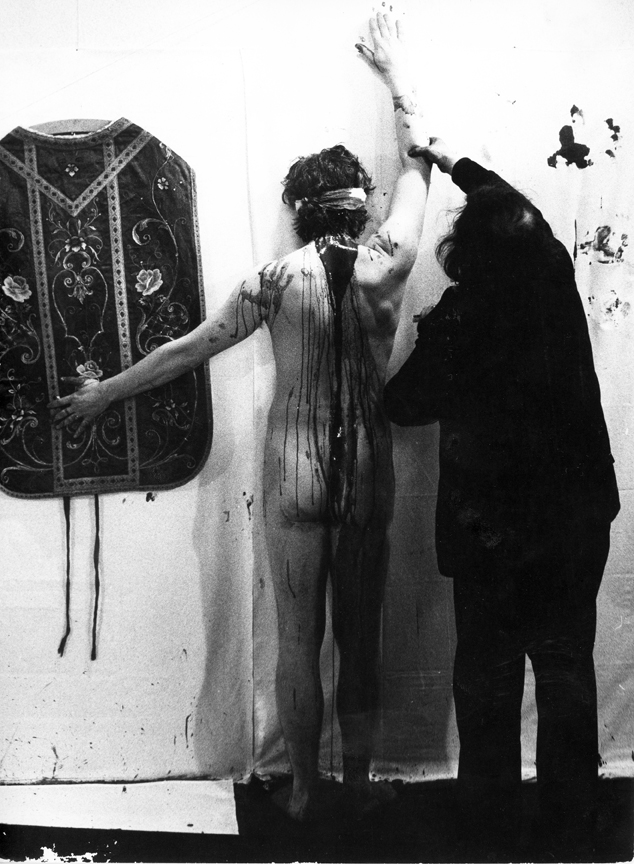

Hermann Nitsch, 100. Aktion, 1998, 6-Day-Play, Prinzendorf Castle and surroundings. Photo: Archive Cibulka-Frey. © Atelier Hermann Nitsch.

P.L. - Why are the participants passive, bound and blindfolded?

H.N. - It’s not only a question of symbolism. I like it. But it is also a matter of symbolism. When a person is killed he is often blindfolded so that he cannot see what they are doing to him. And there are many pictures of the Passion of Jesus Christ where he’s blindfolded. There’s a famous painting by Fra Angelico of a blindfolded Jesus. I like to use blindfolds and bondage, and not always symbolically.

P.L. - Are the participants symbolically being sacrificed, and if so, for what?

H.N. - It’s not a question of sacrifice. Again, it comes back to intensity. I want to show a level of intensity in my theater. I’m interested in the intensity of meat, blood and intestines-the intensity of killing. But don’t misunderstand me. I’m against killing, but when we look at the world we find so many wars, so many killings. It’s a part of creation that people kill each other, and theater takes it as its subject. There is no theater without death. In the story of Jesus Christ there’s death and resurrection.

Hermann Nitsch, 80. Aktion, 1984, 3-Day-Play, Prinzendorf Castle. Photo: Heinz Cibulka. © Atelier Hermann Nitsch.

P.L. - Are women treated differently from men in your actions?

H.N. - I use both men and women. At first it was a bit difficult to use women so I used my friends, but overall I use all kinds of human beings.

P.L. - Is there a score for the performance? Is it planned in advance?

H.N. - Yes, there’s a precise score, but I accept accidents.

P.L. - So it’s open-ended?

H.N. - I would say yes.

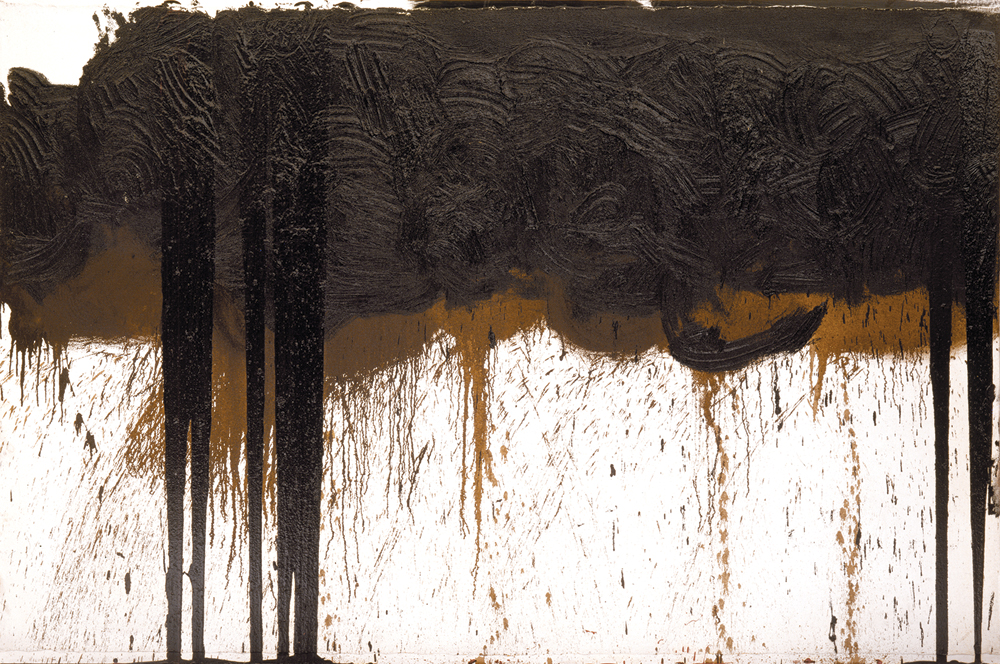

Hermann Nitsch, Schüttbild, 1992, oil on canvas, 78 ¾” x 78 ¾”. Courtesy of Marc Straus Gallery New York and Nitsch Foundation.

P.L. - Do the performances move from order to chaos or chaos to order?

H.N. - I would say both. Both are there.

P.L. - What role do relics-such items as robes, shirts, alters, vestments, religious symbols-play in the performances?

H.N. - A part of my performance is action painting. When you see the performance there’s blood and different kinds of liquids, and if the participants’ dresses and shirts have blood on them-if they are half-dirty-that’s a form of action painting. It’s taking place in reality, not just on a canvas.

P.L. - Why is music an important element of your actions and performances?

H.N. - When there’s a real happening you can feel the reality with all of your senses-with taste, with the smell, with the eyes, with the ears and the touch. Sound in my theater is very important. I use organ sounds that are meditative.

Hermann Nitsch, Kreuzwegstation (Station of the Cross), 1961, emulsion paint, whiting on canvas, 74.8” x 118.11.” Photo: Birgit und Peter Kainz, digital facsimile. © Atelier Hermann Nitsch.

P.L. - Are your rituals religious or spiritual?

H.N. - I’m interested in all kinds of religions and traditions, but I don’t believe in one special religion. I have a very deep religious feeling related to the whole cosmos. It’s a new kind of religious feeling, which is not related to tradition.

P.L. - And with this idea of cosmos, when you are in the middle of a performance, do you feel a relationship with the cosmos, with the universe?

H.N. - When I’m in the middle of a performance the cosmos is everything that is, but also what isn’t and what will be.

P.L. - Does the use of different colors have particular meanings for you?

H.N. - I’m not so interested in the symbolism of color, but I do like the intensity of pure color.

P.L. - Do red and black, which you frequently employ, have any special meaning in your work?

H.N. - I like black a lot. There are many painters who say that ‘black is the king of color.’

P.L. - Are all of your paintings the result of actions and performances?

H.N. - Yes, and very importantly, action painting is a primary product of my theater.

Hermann Nitsch, Schüttbild mit Malhemd, 1994, oil, blood, fabric on canvas, 78 ¾” x 118 ¼”. Photo: Manfred Thumberger. © Atelier Hermann Nitsch.

P.L. - Do you ever paint with brushes or do you prefer hands, sponges, brooms and pouring-more active means?

H.N. - I rarely use brushes. I pour blood, and I like to use my fingers and my hands to smear it around. I’m not a traditional artist. It’s a new kind of painting.

P.L. - How would you define action painting?

H.N. - In the time of Surrealism, automatic writing was a big influence. For me, action painting is much more than just automatic. I use the intensity of the senses.

P.L. - Do you have any boundaries? Any limits? Are there any taboos for you?

H.N. - I don’t give much thought to taboos. It’s difficult. I try to find the reasons for taboos.

P.L. - Are you inspired by classical art, the art of the Old Masters?

H.N. - I like the good and great artists. I like Greek tragedy. I like Bach. I like Beethoven. I like Wagner. I like Schoenberg. I like John Cage. I like Godard.

P.L. - What about literature?

H.N. - All kinds of art have influenced me. I like Ezra Pound. I like Walt Whitman. Symbolist writing is important to me. I like every good form of art.

P.L. - Do you feel a kinship with expressive artists like Jackson Pollock, Yves Klein and Kazuo Shiraga?

H.N. - I like all of them. I was very influenced by the American Abstract Expressionist movement, but music has also been important to me.

P.L. - Do you think your art is against nature or wicked in any way, as critics have often said?

H.N. - My art is nature. It’s not against it. My art is about the development of creation. I don’t believe in the notion of sin. I’m beyond good and bad.

Hermann Nitsch, 47. Aktion, 18 - 20 Ottobre, 1974, Kunstmesse, Stand Studio Morra, Düsseldorf (16). Courtesy of Marc Straus Gallery New York and Nitsch Foundation.

P.L. - What was your response to your 2015 exhibition at Mexico’s Museo Jumex being canceled because of the belief that your art promoted violence through your use of blood and animal parts?

H.N. - It was not the first time people have thought in this way. I’ve often had problems of this kind, but I’m a protector of animals. We have many animals in our house. We have 50 peacock, many chickens, cats, dogs, a mule and a goat, and we love and protect animals. We are against the killing of animals. I never kill them. I buy the animals that I use from a slaughterhouse or a butcher. Society killed the animals I use for my performances, not me. Society kills animals for food. The museum’s administrators have no understanding of art. They have no understanding of me, or my art. They chose to believe rumors.

P.L. - What’s the level of intensity that you hope to reach through your actions?

H.N. - I want to feel that I’m alive. I want to be. I want to fully realize being. I think art is a way of intensity-a way of experiencing very intense feelings.

P.L. - Why do all five senses need to be awakened in your actions?

H.N. - Because we are there and there is no life without our five senses. And-this is very important when I speak of the intensity of our senses-for me there’s no difference between mind and consciousness without the senses. When we use our senses we need our consciousness.

P.L. - What’s your concept for achieving a total work of art, a gesamtkunstwerk?

H.N. - I live in a castle that’s about one hour from Vienna. This is my theater. This is my Bayreuth. This is where I realize my art.

P.L. - Is the castle the center of your universe?

H.N. - The center of the universe is everywhere. It can be in every person. I’m happy that I live in this place, but the center of the universe is everywhere.

P.L. - You’ve created 24-hour actions, you’ve made three-day plays and a six-day play. Is there anything big that you still hope to achieve?

H.N. - I hope that I can realize my last big work in some years to come. It’s the final chapter of my six-day play, which I hope will be my greatest work of all.

Paul Laster is a writer, editor, independent curator, artist, and lecturer. He is a New York desk editor at ArtAsiaPacific and a contributing editor at Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art and artBahrain. He is a contributing writer to ARTPULSE, Time Out New York, New York Observer, Modern Painters, Cultured Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, Galerie Magazine and Conceptual Fine Arts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.