« Face to Face

Interview with Franklin Sirmans

“We believe in the space of the museum, as this is the place where people come together and get educated and entertained at the same time.”

As with most curators, Franklin Sirmans started as an arts writer for magazines, in his case Flash Art and Artnews. Before being appointed department head and curator of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 2010, he worked as curator for the Menil Collection. He also recently curated ‘Prospect.3,’ the third edition of the New Orleans International Contemporary Art Biennial. We visited Sirmans at his LACMA office on January 2015 and discussed some of the topics we consider pertinent in contemporary art: art’s potential to change society, the relationship between high art and pop culture, the challenges of the museum in the 21st century and LACMA’s coming expansion.

BY PACO BARRAGÁN

Paco Barragán - I have known you since the end of the 1990s in New York. You were working freelance and worked among others for the U.S. edition of Flash Art. How did you get engaged with the art world?

Franklin Sirmans - Through writing and an interest in writing about culture in general. I did my B.A. in English and art history. Early on after graduating, thanks to Calvin Reid, I started writing reviews of books for Publisher’s Weekly and had a great editor there in addition to Calvin’s help. I was also writing about music for a number of young hip-hop-oriented magazines like One Word, where my friend Kevin Powell was tearing it up. And, I would write for Sheryl Huggins and Beverly Williams on various projects. I saw early that I did not have the music chops of Kevin or Scott Poulson Bryant who I deeply admired and soon saw that I could have an angle when it came to the visual artists and delivering them to an audience that might not have been familiar with their work. Thus, I started art reviews and pitching the magazines. I got a great letter from Jack Bankowsky that was encouraging but not promising for my immediate future, and so I took whatever I could get. Artnews was the place. I did my first significant art reviews there, in addition to bringing artists to those other outlets like Word Magazine, Shade and Beatdown. Obviously, these magazines were not on the bedside tables of the art world, but it gave me a raison d’être to go to as many shows as possible, and you had to introduce yourself and talk to people because at that time, you also needed to get images, pre-Internet. Best-case scenario would be getting images from the gallery straightaway.

Franklin Sirmans, Terri and Michael Smooke Curator and Department Head, Contemporary Art. Photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA.

P.B. - As with many curators, you started writing and from there transitioned to curating. How was that move? What was the motivation?

F.S. - At that time you could write an article of around 500 words about a solo show. As we know, that number seems to have gotten smaller and smaller. So if you wanted to write a bigger article it was only possible if you wrote about more artists. And it became this idea or concept around the work, if you will, of making an exhibition through bigger articles. So it seemed desirable to make these articles and thoughts into three dimensions.

P.B. - In my case it was a bit like that because when you wrote a bigger article with different artists around a same topic I always had the idea of somehow curating an exhibition, but on paper.

F.S. - Yes, exactly!

Installation view. “Fútbol: The Beautiful Game,” (February 2 – July 20, 2014). Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA.

BETWEEN THE POLITICAL AND POP CULTURE

P.B. - If we look at your CV, we find a series of exhibitions that deal with sociopolitical issues-from the most recent biennial in New Orleans titled ‘Prospect3: Notes for Now,’ ‘NeoHooDoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith,’ ‘Basquiat,’ ‘Americas Remixed,’ ‘Rumors of War.’ Do you understand curating as a tool of sociopolitical activism? If so, maybe you could give us some examples of how some of your exhibitions or artists engage with it.

F.S. - I wouldn’t define it that way. I would say that I hope I have a voice, one that is perhaps informed by the world we live in and the events of our times. I came out of a conversation like many of us with people like Harald Szeemann. So the foundation of making exhibitions is one of, or at least some sort of, political consciousness or social interest. Even if we do an abstract show, like the one we are doing now like Variations: Conversations in and Around Abstract Painting, there is always something there you’re trying to say.

Installation view. “Variations: Conversations in and around Abstract Painting,” (August 24, 2014 – March 22, 2015). Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA.

P.B. - In this same political sense, and referring to Prospect.3 you just curated, Julia Halperin wrote in The Art Newspaper the following title: ‘A Better Prospect for African-American Artists.’ You seem to have included more than 60 percent Afro-American artists.

F.S. - Well, I think it was interesting as she put statistical information I wasn’t aware of-it was surprising to me as I was not thinking about the numbers, only about the artists and the resonance to New Orleans.

P.B. - And what about this general complaint by some art critics and artists that curators only use artists to illustrate their ideas?

F.S. - One thing that I stick to this is Walter Hopps’ quote: ‘The job of a curator is to find a cave and hold the torch.’ This is the place you can put the work, and I’m going to help you light it and present it in the best possible manner according to myself and the artist. I think it is a healthy circular conversation, right, because you don’t come up with an idea for a show without thinking about the art work. So the art has to be telling you something, no matter what you are reflecting about outside the studios.

P.B. - Yes, exactly, many times we walk around and we see artists dealing with the same topic.

F.S. - And we pick up on this subjectivity.

Hew Locke, installation View at Newcomb Art Gallery, Tulane University for Prospect.3: Notes for Now, a Project of Prospect New Orleans, (October 25, 2014 - January 25, 2015). © Scott McCrossen/FIVE65 Design

P.B. - Another angle of your curatorial practice has to do with pop culture and expanding the limits of the white cube. How do you understand the relationship between high art and pop culture?

F.S. - I like to think around those spaces. My curatorial entry point was through music with One Planet Under a Groove: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art, curated with Lydia Yee at the Bronx Museum in 2001. And then wanting to explore that through sports several times, most recently here at LACMA with Futbol: The Beautiful Game.

P.B. - Next time you better invite me, as I’m a frustrated soccer player.

F.S. - (laughter) Of course. It’s a show that needs to be revisited every four years, obviously.

‘NEW’ BUILDINGS FOR ‘OLD’ COLLECTIONS

P.B. - You have worked for LACMA since January 2010. Between 2006 and 2010 you worked at the Menil Collection in Houston. I guess that one of the reasons why you were appointed department head and curator of contemporary art at LACMA was precisely because of your experience and passion in working with the permanent collection.

F.S. - Yes, I love that. It started with teaching at MICA (Maryland Institute College of Art) and Princeton and doing those crazy survey classes of the 20th century, and the ability to talk from Cézanne to the present is actually fun, but being able to actually see those pieces there is nothing like it. And to be able to work from that background of something that has a foundation and a reason for being that goes back over a hundred years I find so fascinating.

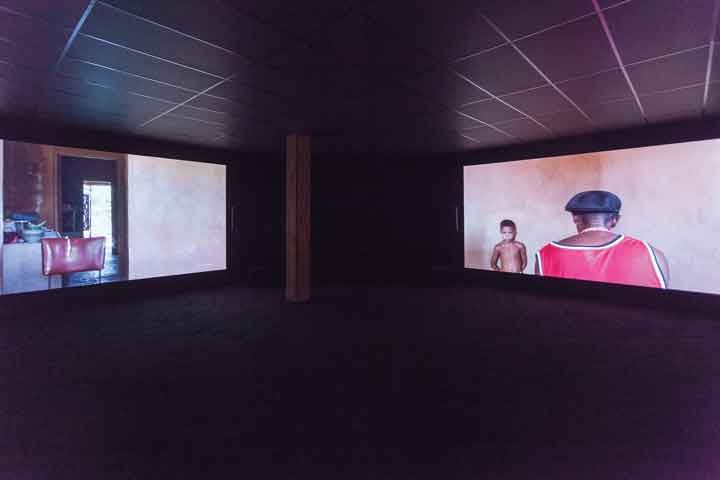

David Zink Yi (b. 1973, Lima, Peru), Horror Vacui, 2009, two-channel HD video installation, duration: 120 minutes. Installation view at the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans for Prospect.3: Notes for Now, a Project of Prospect New Orleans, (October 25, 2014 - January 25, 2015). Courtesy of the artist; Johann König, Berlin; and Hauser & Wirth, Zürich, London, New York. Photo © Scott McCrossen/FIVE65 Design.

P.B. - But isn’t it a reflection of these five buildings that have been squeezed together?

F.S. - Of course being in an encyclopedic space like this and to learn how artists of today teach us about art of the past is something that I find really illuminating. Working with Ai Weiwei and being able to present his 21st-century art inspired by the zodiac sculptures and history of the original sculptures at the summer palace outside Beijing made in the 18th century is exciting! Then we have a set of jade sculptures from the 19th century that were made by an artist who was also looking directly at the summer palace! That sort of layering and revisiting of history is informative and beautiful. Or, take a look at how Jorge Pardo’s relatively new designs for the Pre-Columbian Collection give you a new way of looking at the work of the past.

P.B. - How can we engage from your point of view with a permanent collection in order to try to make the experience more accessible and attractive for the audience, and especially younger audiences?

F.S. - I had a meeting this morning with Tavares Strachan, who is working on a project with our art and technology lab. It’s an initiative that has started up recently, inspired by the spirit of LACMA’s original Art and Technology program (1967-1971), which paired artists with technology companies in Southern California. So this past weekend Tavares did workshops with kids aged five years to eight years old, and he facilitated conversations between them and scientists at the corporation SpaceX. From there, together they made drawings from which he’s going to use and reference and create new works for an exhibition here. In the process, and when the work will be up next fall, we will have some kids functioning as docents. This means that they will be walking around with special uniforms on, taking adults around the museum and telling them about the artworks. So this is one way of engaging with an audience.

P.B. - So this brings us to the question: What are the challenges of the museum in the 21st century?

F.S. - To be relevant, to make it matter in terms of audience participation. We believe in the space of the museum as this place where people come together and get educated and entertained at the same time-potentially in equal parts. And how do you sustain that engagement, especially amidst all the other things that are available? The museum is hopefully an in-between space for daily life where we can all come to turn on or turn off and recharge our senses.

Tavares Strachan (b.1979, Nassau, Bahamas), You belong here, 2014, video recording of blocked out neon sign on the Mississippi River and Industrial Canal. A project for Prospect.3: Notes for Now, a project of Prospect New Orleans, (October 25, 2014 - January 25, 2015). Courtesy of the artist. Production: David Meinhart, Joseph Vincent Gray, Michael Hall, Chris Hoover, Speed Levitch, Erica Sellers, Bob Snead, Taylor Snead, and Christopher Thompson. Photo © Vincent Gray.

AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION AND SOCIAL MEDIA

P.B. - Are expansions in general -think of SFMOMA, MoMA, Rijksmuseum, The Prado–absolutely necessary?

F.S. - Actually, yes.

P.B. - In this same sense, what will architect Peter Zumthor’s project mean to LACMA?

F.S. - Only time will tell. But it is going to be transformative and certainly will engage space in a way that will be complimentary to a 21st-century museum experience.

P.B. - Could this respond to the pressure of art having to compete with pop music, cinema and other sorts of entertainment? Are we able to compete with them?

F.S. - I think in some ways that’s our strength: We don’t play to the common denominator. We play from a position that is unique, a position that is very focused, a position that is very considered, one that has taken a lot of time to conquer. So that’s our strength. I come from the old cliché of poetry. One point in time the poet was hot and then not. These things go in cycles. Part of an expanded museum in the 21st century is that it functions in so many ways.

P.B. - As with most professionals, you’re engaged with social media like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram et al. How do you think social media have shaped or impacted the art world?

F.S. - Too many ways to discuss here and now. And I think I will have an even better idea after seeing Lauren Cornell and Ryan Trecartin’s New Museum Triennial show that opens February 25.

P.B. - Finally, some of the most recent shows you’ve curated are ‘Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye’ and ‘Variations: Conversations in and Around Abstract Painting.’ What are the shows you’re working on now?

F.S. - Yes, ‘Variations’ is up through mid-March, and then we are installing ‘Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada,’ which will open in June and be up through early fall. In 2016, there is the project with Tavares, and we are hosting the Agnes Martin exhibition from the Tate and present Toba Khedoori in the fall of 2016.

P.B. -A pretty packed program. Thank you for your time.