« Dialogues for a New Millennium

Interview with Gamaliel Rodríguez

Gamaliel Rodríguez, Figure 1737 (detail), 2015 - 2016, ballpoint pen, acrylic and colored pencil on paper, 76" x 648" ( 7' x 54'). Commissioned by SCAD Museum of Art Savannah. Courtesy of the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Miami.

“I often see progress as retrogression.”

“I often see progress as retrogression.”

Puerto Rican artist Gamaliel Rodríguez (1977, Bayamon) has from the very beginning achieved a particularly recognizable style. His eerie and intriguing work deals with concepts like memory, history and vigilance and is rather “un-Caribbean” in style.

By Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán - Puerto Rico is a small island with an intense artistic vibe. How did you get interested in the arts?

Gamaliel Rodríguez - I started to get interested in art from an early age, but decided to take art seriously when there was nothing but study at the University. That was at age 23. I thought college was not for me, not even when a former girlfriend told me I had a talent for drawing. It’s when I convinced myself to study art that my life changed. That’s when I felt in love with the arts, its history and how artists in Puerto Rico had the ability to absorb outside influences and then create their own voice.

P.B. - In 2004 you earned a Bachelor of Arts in communications in visual arts at la Universidad del Sagrado Corazón in San Juan de Puerto Rico. What does the program consist of? Is it a mix of communications and visual arts?

G.R. - Yes. It is a program entirely of communication, both for television, radio and the press. It had a sub-concentration in visual arts but more like for illustration, typography and very little visual arts. In fact, in that program I only took three courses in drawing and a single painting course. Everything I have learned has been with pure practice at the workshop. Maybe what I learnt best is how, like with communication, you can apply the same concepts: emitter plus channel or more communication method plus receptor is an effective communication if the receiver understands the message code. It is very evident in my art. I like to communicate indirectly and create feelings that can be perceived by the visual senses in this case.

P.B. - Then in 2005 you went to Kent, England, where you earned a Master’s of Fine Arts degree at the University of Kent. Practically all your colleague artists from Puerto Rico proceeded to studies in New York or other cities like Chicago. Why did you decide to go to England?

G.R. - I will be very honest with you: I studied there because it was the only place I got accepted. SAIC of Chicago did not accept me because I had not enough painting classes. The same happened at RISD and even Mexico. Furthermore, it was not a good time for artists or painters there in Kent, England. The school was more theoretical: 80 percent theory and analysis of major theoretical study and only 20 percent of studio practice. I thought I would learn painting at large and acquire a great knowledge in materials, but it was pure reading. In fact, the program supported the use of alternative means instead of traditional media. I remember in 2005 Saatchi did a show called “The Triumph of Painting,” which he divided into three parts in London. I remember that I had no money there. I took the first bus in the morning at 5:50 a.m. to London for a British Pound and the last bus back at 11:15 p.m. for the same money. I collected money to see these exhibits, and I was convinced that painting and drawing were still solid.

P.B. - And in 2011 you did a residency at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. Why Skowhegan?

G.R. - Skowhegan serves as a site for exploration and experimentation of ideas with great artists, helping to clarify your doubts for a period of nine weeks. It’s where it ends. It was a unique experience and definitely helped me a lot to see how I could evolve my work without fear of being wrong. Every artist should not be afraid to fail in a work because there are no parameters that say otherwise.

P.B. - And besides several awards like the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and the McDowell Fellowship, you finished in 2013 a residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York. What has the ISCP meant to you?

G.R. - After I finished my master’s I had to return to Puerto Rico basically empty-handed and with the debt of my studies. I took me four years to make myself known on the island. It is after four years that then suddenly all the major art residencies started to accept me, and it opened other doors-awards and so on. The International Studio and Curatorial Program was more like a workshop or a place to work in NYC that allowed me to show my process and my ideas. It helped me reaffirm what to do and adjust certain aspects of what I was doing. I had many good reviews from the program, field trips to museums and institutional spaces in NYC. Thanks to the program, I now reside six months in NYC and six months in Puerto Rico.

PROCESS VS. CONCEPT

P.B. - Yes, I understand perfectly what you mean about doing all those residencies. Let’s talk about process before talking about concepts. You always work in series, and some times you work on different series at the same time. Tell us about how you envision the process.

G.R. - For me, my ideas help me to select the medium and the material. Obviously, my works are bi-dimensional, but what changes is the material such as ballpoint pen, Sharpie or acrylic. The idea of working in series comes from the image you intend to communicate, often rather literal, direct with written information underneath or, recently, with images that are not understandable, no time references that look like photographs of the 1950s, but with elements of the future. Each series allows me to expand my ideas and not focus directly on a single style. I do not think that in the 21st century one must keep making the same style till the end of their days. The idea that recognition by one style, the ‘discovery’ of a style that later becomes a house style is something that does not interest me. I have no problem with creating different series that are not equal. My problem would lock me in one style and not being able to transcend my ideas. I’m not a painter, but I am an artist using the medium of drawing and painting as a communication channel.

P.B. - In the very first series, “Figures,” you used the traditional blue ballpoint pen and text on paper. Why did you use ballpoint? It makes it pretty uncommon these days while on the other hand it reminds us of books and printmaking.

G.R. - The idea behind using ballpoint pen was to create an illusion of engraving. The effect achieved is very good. It seems like dry point or etching, but ultimately it is a drawing, it is a unique piece. The text was just as important because it created this effect of old information, declassified, like confidential files.

P.B. - In the series “Issues” you switched to acrylic on canvas, and in series like “Dark Thoughts” you use felt-tip pen and acrylic on canvas. Does this shift in the use of materials respond to a shift in concept?

G.R. - The “Issues” series was a series of realistic work of largely declassified images. The selected color in these works was the result of scanning all photos to determine what the three recurring were in those found images. It was basically blue, gray and sepia. This series is completely in acrylic.

The “Dark Thoughts” series is possibly a reflection of the “Figures” series and follows the same reference number, example: Figure 1789, 1790, etc. This series is much darker, more vague, it’s so difficult to understand even for myself. But it’s an outlet or a release valve. The less you know what is happening in the picture, the better. These aerial images look like spy photos, but the different elements that make up the image as buildings, industrial areas, cliffs, beaches, etc., are not entirely correct. It can’t be determined whether the image is real or not or if the light of the work is natural or artificial, as if I had created a model to portray and then re-create the picture. I really understood that drawing in ballpoint pen only limited me, as if there was no freedom of gesture, as the ballpoint pen has its own limitations. This new series allows me to exploit the image itself.

REAPPROPRIATION AND RESIGNIFICATION OF IMAGES

P.B. - In a general sense we could state that your work deals basically with how we construct and relate to images in our image-driven society. It has a semiotic point of departure.

G.R. - I agree. My work focuses on social issues, but recently the work has taken on a turn more toward the non-relational. The images that I use, that I appropriate, deconstruct and/or reconstruct come from facts. For me, my work is related to topics. Semiotics is becoming more palpable when we stumble upon the new system language, the apps. Everything points to an oversimplification where words become a symbol, almost a pictogram.

P.B. - In your first series, “Figures,” power in all its possible forms-political, economic, psychological, physical-becomes the key protagonist.

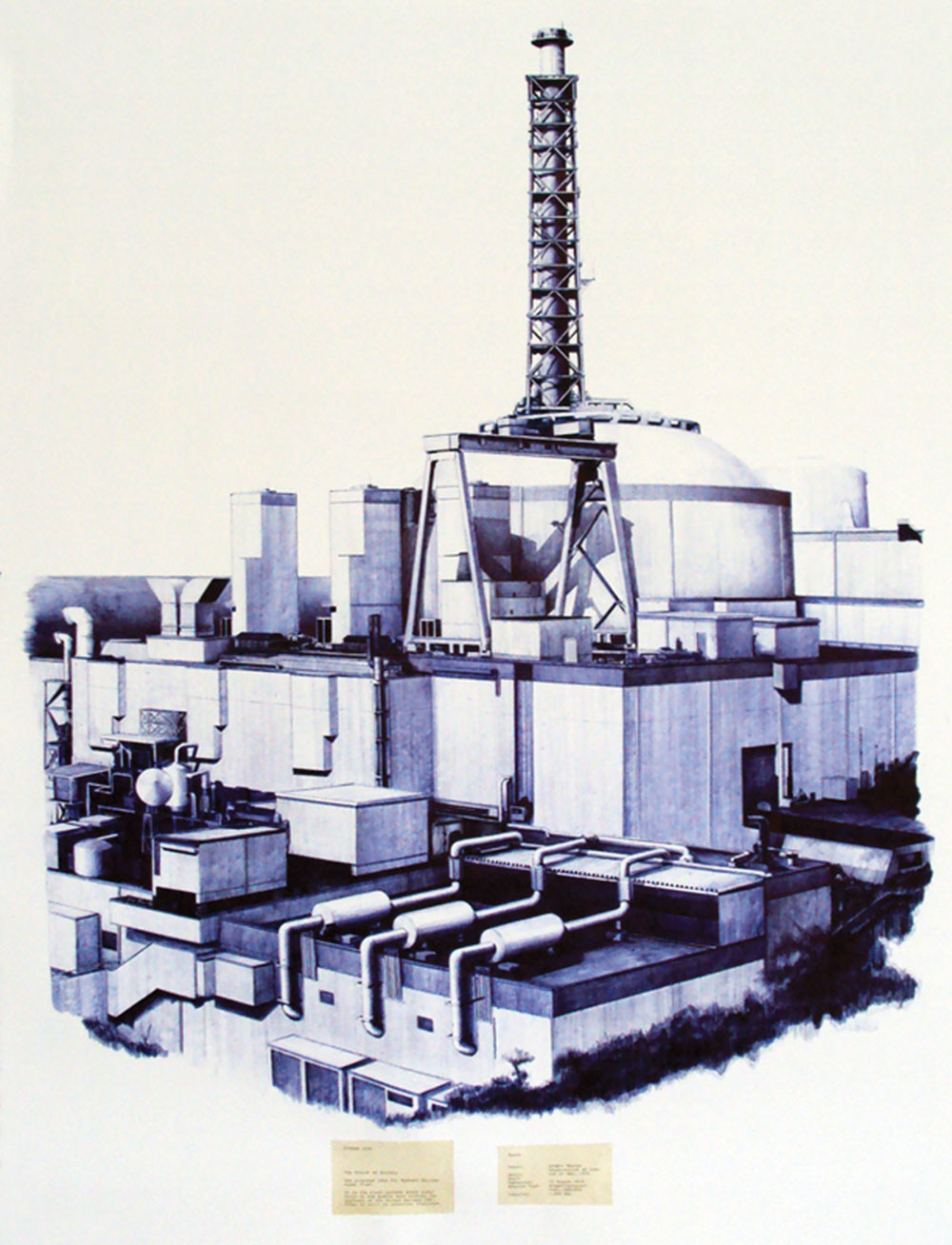

G.R. - Definitely. The term or the word ‘power’ involves a series of definitions that can be used in different areas. What interests me more is the tactile representation, the object, the structure, the physical form that involves defining power. One of the best examples is the temple of a church, a power generator, a nuclear reactor, a military tank, a national defense building, a rifle, a library, a university. All of them seek to use the term in different ways, as the church, the power of religion, faith, the university or the library, the power of knowledge, military power, economic power, political power, the power of drug trafficking, etc.

P.B. - This could be connected to Foucault’s idea of ‘power-knowledge’ and his concepts of ‘episteme’ and ‘discourse,’ which every society reproduces once and again and in a particular manner.

G.R. - It is because our social system is almost similar throughout the world. There is always a worldwide commitment to ‘development,’ but what’s the definition we give to the word. It can be varied depending on your needs or eccentricities. Sometimes the power comes from the excessive thinking that we are smarter than others or thinking that our economy is richer than the others. Power is an amazing item, it’s addictive, it’s almost like a drug. If we study the whole history, then we would realize that it is basically due to the fact that reason is conditioned by factors that precede it. Security comes from insecurity.

P.B. - Can we read works like The Church of Anxiety, The Centre of Knowledge or Smartville as a reminder of the failure of progress and utopia?

G.R. - The definition of utopia for me is more like the faith of the church. It is a goal which is not finite, but in the end it is what it seems. I often see progress as retrogression. It’s like watching modern technology: It means we are locked in our own world and not even say good morning to each other on a bus, on a public train, on the street, etc. Progress in my work is a reflection of a failed attempt to be more efficient, more evolutionary. Humans see the banal and the created needs as basic needs. When I raised the idea of the church of anxiety, which was the nuclear reactor in Iran, its facade looks more like a church than anything else. It’s mixing church and science in their basic needs, the human dependence on these two entities. So does Smartville or the Centre of Knowledge (CIA), which was the union of different intelligence buildings coexisting in the same plaza.

Gamaliel Rodríguez, Figure 1746, 2015, felt tip pen and acrylic on canvas, 108" x 96." Courtesy the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Miami.

P.B. - In your next series, “Issues,” you re-appropriate declassified photographs that you re-signify. What motivated the interest in these images?

G.R. - The idea behind “Issues” was to recode the images with the medium of painting alternating the message that produces the photo and enchanted with the notion of paint. These images that I have been finding are small in size. I like to expand the images, the meaning and the idea for which it was created. Declassified images are the other 50 percent of the story that has not been written. Humans have created the notion of national security and on behalf of this have committed many crimes.

UN-CARIBBEAN LANDSCAPES SEEN FROM ABOVE

P.B. - You also presented “Landview” at Galería Walter Otero in 2015. It consists of a series of landscapes seen from above.

G.R. - The next thing would be a series of landscapes seen from above that look like it is a satellite imagery created by my imagination. I’m looking for structures and places on the island that are not related to the term ‘tropic,’ such as nuclear reactors, oil refining plants, bunkers, military flight radar protection, among others. When you hear about it, it is not the common denominator of tropical countries like palms, beaches and all that makes part of the touristic package the country is always selling.

P.B. - Yes, you are right. Nevertheless, works like Adverse Effects or The Palmitic Nap allow a more general reading-protest against war and capitalism-but also a more local one: the napalm experiments on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques, which the U.S. Government used because of its botanical similitude with Vietnam.

G.R. - All the works that I have been doing since 2009 have some connection to Puerto Rico. My work is not a direct view of the island. What I often do deals with in part our history, specifically in the context of being of the Greater Antilles, being Caribbean, but being part of the United States at the same time. My practice is not a reflection of our history, but there are certain historical elements that you may find in it. For example, in Puerto Rico, many tests were conducted to test the effects that could have happened in Vietnam, the deforestation of tropical forests using powerful chemical agents. In Vieques, one of the small islands that belong to Puerto Rico and also hosted one of the important U.S. Naval bases in the Caribbean, the napalm bomb was tested and its effects were analyzed. Later on, these bombs were also used against humans in Vietnam in clear violation of the Geneva Convention. This is why these images are important to me. They are pieces of stories to be reinterpreted through large-format paintings. It is almost like creating a banner or advertisement of what happened.

P.B. - The series titled “Dark Thoughts” could be read as a continuation of the “Figures” series, both formally and conceptually speaking. In this case, you added elements like smoke and fire, elements that in our contemporary society could presuppose ideas of (chemical) disasters, (bomb) attacks, terrorism…

G.R. - I could not really specify what happened in this series of work. For me, the result of working with so much aerial imagery allowed me to create my own airspace without any visual reference. The other aspect that I analyzed is the smoke as an illustrative code. In the history of humanity, smoke and fire could produce a series of sensations to us depending on the situation that occurred. Our primitive part of the brain (limbic system) could recognize smoke/fire as a familiar/natural manifestation. In the 21st century an image of a structure, a unity, a system, a space, a location or an object covered by smoke and flames could be read as a raid, malfunction, miss-firing, oppression, liberty, the end or the beginning, terrorism, anarchy, civil rights, manifestation, sublimation, sabotage, etc., that it can be related in political terms. How such a simple reaction of combustion can be reinterpreted as a complex analysis of insecurities, especially in the era of mass communication systems.

P.B. - So, your work could be understood as a dialectics between history and memory, between grand narratives and micro-narratives, between history written by the victors and the forgotten memories of the common man.

G.R. - That’s a very nice way to see what my work is about. Many people believe that my work reflects a degree of pessimism, but I explore more in reflective mode. I reflect how things happened through the past and could be repeated in the not too distant future. The problem is that in these times, our memory is very short, it is very small. I think that artists of the 21st century must have new approaches to what art is. A concern may manifest through the artistic process without being partial. My work does not look for guilty or innocent people. I do not intend to give my personal opinion through my work.

Gamaliel Rodríguez, The Church of Anxiety, 2010, ballpoint pen and text on paper, 38" x 50." Collection of Museum of Fine Arts Boston (MFA), Boston. Courtesy the artist and David Castillo Gallery, Miami.

P.B. - I would like to go back to the idea of being Caribbean from Spanish roots and at the same time belonging as a citizen of the Free Associated State of Puerto Rico to the U.S. I see in this tension, this kind of schizophrenia, an important artistic motor for many Puerto Rican artists. Do you share this opinion, and how do you handle this situation yourself on a more personal level?

G.R. - I try to concentrate as a citizen who lives day to day in our country. A person who pays taxes and tries to survive in a country that is bankrupt. I try not to see our political situation as a topic to discuss in my work. I very much agree with you on the question of how Puerto Rican artists have used this issue for a long period, the question of who we really are. But now I tell you that there is a new era of local artists with artistic approaches that have focused on the art and not on our identities. I think this time of schizophrenia has decreased and is now a vibrant scene that focuses more generally on art, global similarities using Puerto Rico as a base, a home, and has been able to develop a connection of ideas with the rest of the world, share the same artistic language.

P.B. - Finally, tell us what you are presenting now at SCAD in Savannah under the title “Reminiscent of Time Passed.”

G.R. - It is a large-scale drawing, about 54 feet long and seven feet high commissioned by the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia, and instigated by the curator of the solo show, Aaron Levi Garvey. The drawing is the result of a conversation and a studio visit in New York when I was living there doing the Bronx Museum of Arts AIM Program and the Third Bronx Biennial. My last visit to Georgia was in 1999 when I was at the Infantry School at Fort Benning. It was for a period of 15 weeks, and since then I never came back. I created the large piece made of my memories of the place. I did a study of the perspective, but the whole image made in the drawing comes from my memories of a vast landscape, long road marches, woodland and military facilities or complex. I started the work in Puerto Rico and the museum encouraged me to finish it in situ, in the gallery. The experience was great because I didn´t recall so many details from my memories, but rather a more general panorama that I tried to re-create. The work has this feeling of past and at the same time, future, to it. You can’t determine the hour or the relation with space and time. It was a great opportunity to explore my thoughts about it.

Paco Barragán is the visual arts curator of Centro Cultural Matucana 100 in Santiago, Chile. He recently curated “Intimate Strangers: Politics as Celebrity, Celebrity as Politics” and “Alfredo Jaar: May 1, 2011″ (Matucana 100, 2015), “Guided Tour: Artist, Museum, Spectator” (MUSAC, Leon, Spain, 2015) and “Erwin Olaf: The Empire of Illusion” (MACRO, Rosario, Argentina, 2015). He is author of The Art to Come (Subastas Siglo XXI, 2002) and The Art Fair Age (CHARTA, 2008).