« Dialogues for a New Millennium

Interview with Han Nefkens

“I would not advocate a system where private individuals dictate what should be shown and what not in a public museum.“

Dutchman Han Nefkens (Rotterdam, 1954) is a passionate collector based in Barcelona whose major joy is sharing what he has with others. Instead of the traditional idea of owning works, most of his art is bought in a fruitful dialogue with museums and goes straight to them through the H+F Collection. We spoke to him about the changing nature of collecting, the relationship between private and public, and the state of the market.

By Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán - In order to contextualize your personality for an American audience, lets start with the two basic questions: When and why did you start collecting?

Han Nefkens - I started collecting in the year 2000. I started collecting because I had discovered an exhibition by Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist, and I was very impressed by the way she managed to make you feel part of the artwork. And I thought, this is a world in which I want to have a role. But I never had the idea of becoming a collector just to amass things. Right from the beginning I knew that I wanted to share what I liked with other people.

P.B. - You are a writer, so creativity is in your alley in a way, and I guess arts have been always part of your interest.

H.F. - I think so, as when I was a child I was always surrounded by art-not contemporary art, per se, but all kinds of artistic objects, from statues to tapestries and paintings. And what was very important is that from a very young age, I started to go to museums with my parents. I literally liked to ‘get lost in art.’ I remember sitting in front of a painting by Kees van Dongen at the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, and I would just stay there staring and looking at it and making up my own stories about the woman in the painting. And that feeling of being involved with the artwork, of having a dialogue with the artwork, has always stayed with me.

David Goldblatt, Victoria Cobokana, housekeeper, in her employer’s dining room with her son Sifiso and daughter Onica, Johannesburg, 1999. Victoria died of AIDS 13 December 1999, Sifiso died of AIDS 12 January 2000, Onica died of AIDS in May 2000, 1999, photograph (digital print/pigment ink), 33.5” × 41.7”. On long-term loan to Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, NL.

FROM WALL STREET TO THE MUSEUM

P.B. - Previously you invested your money in Wall Street in bonds, stocks and deposits. Was the decline of Wall Street end of the ‘90s the stimulus to buy art?

H.F. - Well, it’s not exactly like that. The bare truth is that I used to invest the allowance I got every year in bonds, stocks and products like that. Until the year 2000 when I found out that I would get much more pleasure putting it into art, and so it was not as an investment at all. As a matter of fact, the works would go directly to different museums as a ‘promised gift’ when I die-they will be owned by the museums. So it meant that money that I would use for investment I now use for my art projects.

P.B. - So the H+F Collection kicked off in 2000 at Art Basel. What did you do to enter the art world as a newcomer?

H.F. - Yes, when I decided that I wanted to collect art, for one whole year I didn’t buy anything. But what I simply did was start going around looking, going to art galleries, art fairs, museums, and I talked to artists, gallery owners, museum directors, curators and so on just to get a good picture of it. And it happened that via a friend I got in touch with Sjarel Ex, at the time the director of the Centraal Museum in Utrecht. And as we got talking and I expressed to him my vision of sharing what I liked with other people, his answer was: ‘Well, if you buy something that fits in the collection of the museum, we will gladly accept it as a loan.’ So, even before I bought anything I already knew that the possibility existed that it would go to a museum. And that gave me a completely different look at what I was buying because I hadn’t had the limitations a regular collector has when hanging it in his or her house, no storage problems; I could buy series of works, big sculptures, installations… basically I could buy things that fit into a museum. Thus, right from the very beginning the perspective changed, as I would buy works with the idea of having the works exhibited in a museum.

P.B. - I guess that the fact that you learned that you were HIV positive in 1987 changed your life drastically?

H.F. - It affected my life in different ways because in 1987 you were probably going to die pretty soon as there was hardly any medication available. That led to the idea that I had to live every moment as it was the last moment of my life. But, having said this, I have to admit that I was very fortunate, as I got the medication I wanted in the time I needed it, and I survived. So, this feeling of living the moment is still part of me. One comes to realize in moments like that that life is not endless, which is a sentiment that of course a young person doesn’t cherish. This also engendered in me the need to share whatever I think, whatever I have, whatever I write…

P.B. - What would you say is characteristic of your collection? Are there some guidelines or red lines that cross the collection?

H.F - I started of course to buy according to my intuition, but after a couple of years when the first exhibition was made I could see clearly some red lines through the collection. One characteristic is a strong poetic element in the works; another is a ‘contained strength,’ which is not always obvious, but the strength is there in the work; furthermore, we find quite a lot of works by women artists, but this is something unconsciously as somehow they have this poetic element and hidden strength I like that appears to be more prevalent among women artists. Another aspect would be that my collection is very global, very international, with works by artists from Europe, United States, South Africa, Thailand, Japan-many different countries.

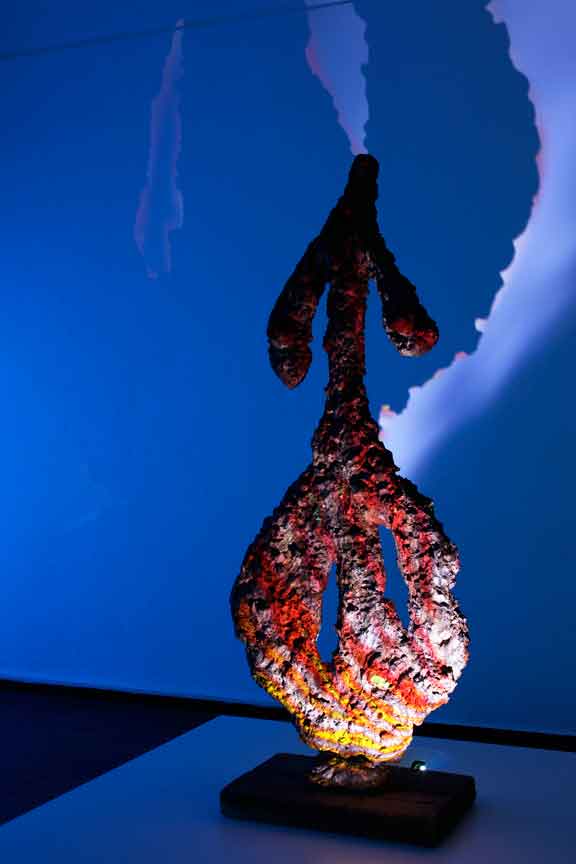

Pipilotti Rist, Double Light, 2010, video-installation (projection on a work by Joan Miró). Gift to the Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona, ES.

P.B. - What is surprising is that from the very beginning you started a close collaboration with Sjarel Ex, the former director of Centraal Museum in Utrecht, which resulted in a long-term loan agreement.

H.N. - In that period a friend of mine contacted with different directors of museums in the Netherlands, but none of them were interested in talking to me. Only Sjarel Ex, and that’s also the reason why I have such a special relationship with Sjarel and we continue working together. Once I started, other museums became interested.

P.B. - This is now happening with other museums like the Folkwang Museum, Museum of Reykjavik, Huis Marseille. How did this come about?

H.N. - In the case of the Folkwang Museum, they actually got interested in some vintage prints I bought by Stephen Shore, and they showed interest in having these prints. Also, not everything I bought fitted in the collection of the Centraal Museum, and so I got to talk to other museums like De Pont, Huis Marseille in Amsterdam, and we started to work together.

P.B. - Another of your patronage activities is the H+F Curatorial Grant that started in 2007. Can you tell us how this idea came about?

H.N. - This was an idea that was born from a conversation I had with Hilde Teerlinck, who is the director of the FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais in France, and she is also the curator of many of my exhibitions. And we discussed the need we felt for young curators to be involved in our different projects. And we realized that what happens with young curators is as they come out of school they often work in museums, where they fetch coffee or make copies at a photocopy machine. And we decided that there was a real need to provide young curators at a very young age practical experience in making exhibitions. And on the other hand, there was a need from our side to help us with our exhibitions. And this is what I would say is a win-win situation. And this grant has been very successful so far, and now were doing the fourth edition. It’s specially focused on young curators.

A FRAMEWORK FOR THE PUBLIC AND THE PRIVATE

P.B. - Its obvious that you are not interested in art as investment and that most works will be donated to museums, but it’s a fact that in the last decennia, art has become more and more speculative like a casino, and art prices has rocketed shamelessly.

H.N. - It’s the effect of life. Of course, there is a lot of money in the world going round these days, and there are many hedge funds, and there are the emerging markets like Russia. But the fact is that there aren’t too many investing opportunities because banking rates are very low, the stock market is very uncertain, so people are looking basically for places to park their money. It’s unfortunate that they found the art world to do, as they push the prices up and, secondly, it’s unhealthy for young artists who see that the prices of their work go up all of a sudden because it is seen as a speculative investment. And an artist needs time and tranquility to develop his or her work. On the other hand, I must say that there are a lot of people who earned money that are being benefactors and doing good things in a sense that they become patrons, start museums and foundations. I think that it is very important in the art world to have a warm heart and a cool mind.

P.B. - In this sense it’s more and more complicated for museums to buy art at these prices. This would encourage private funders joining forces with museums, especially in Europe, where public funding is declining more and more-see for example the Netherlands.

H.N - Well, that’s exactly what I’m doing of course. I had the development from a collector that lends works he buys to museums to somebody who starts producing; the last years I didn’t buy any single piece of art but produced with my foundation art works together with museums. You give the artist a chance to make a work that otherwise would be difficult to produce. And it also means that I can show my confidence in the artist by giving him or her a consignment. I think that this is a part in which many more collectors could be involved with. And I think here is an important role for both the public sector and private individuals to construct the framework through which individuals and art institutions can get together, a kind of matchmaker as it were. There is obviously a need on the part of museums and other art institutions for funding, and there is also a need for individuals to become engaged with the art world.

P.B. - This way of working is still very rare. What do you think we need, or what should the state do to foster these kinds of private initiatives?

H.N - There should be an information bank where the needs of museums and art institutions are catalyzed and where individuals can see what’s of their interest. This is something that the public sector can set up.

P.B. - But if we see the American example, we see that too often people buy their way into museum boards and start putting pressure to have their artists exhibited. Is that not a real danger?

H.N. - This is also why existing models should not be copied but new concepts should be developed. In Europe especially it’s very important for museums to maintain their identity and their integrity. And in this case the figure of the museum director is of vital importance, as he or she needs to know exactly what he or she wants. So, this is also much easier for an individual to see if you fit or don’t fit with that philosophy. I would certainly not advocate a system where private individuals dictate what should be shown and what should not be shown. There is room enough for other initiatives. And private investors can learn from the museum, but the museum can benefit from the collector’s network too. Basically, it can generate an interesting dynamic.

P.B. - Collecting is changing slowly from being object- to idea-based, id est, not so much owning an art object but sharing an idea and making it possible. How do you expect collecting to evolve?

H.N. - I think that’s a general development in society what you’re a pointing out. People become less and less interested in owning things because there is hardly anything that is exclusive anymore; people are more interested in experiencing things. Translated to the art world, it means that there are many opportunities to experience things through exhibitions, performances and art forms that do not necessarily leave something tangible behind.

P.B. - Social Media, iPads, iPhones, new technologies. How does that affect you? Actually, I got your contact via Facebook.

H.N. - I’m definitively interested in that. I have a website for the foundation, and I’m also active on Facebook, which is a wonderful way of connecting with people and bringing works to a greater audience. For example, we have the H+F Collection on Facebook, where each week we highlight one work from the collection with extra information. And an important advantage of social media is that you have access to art in other countries where you would normally not know about it-art in Thailand, Indonesia. It’s very challenging.

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust in New York. He recently curated “The End of History…and the Return of History Painting” (MMKA, The Netherlands, 2011) and “¡Patria o Libertad!” (COBRA Museum, Amsterdam, 2011). He is co-editor of When a Painting Moves…Something Must Be Rotten! (2011) and the author of The Art Fair Age (2008), both published by CHARTA.