« Dialogues for a New Millennium

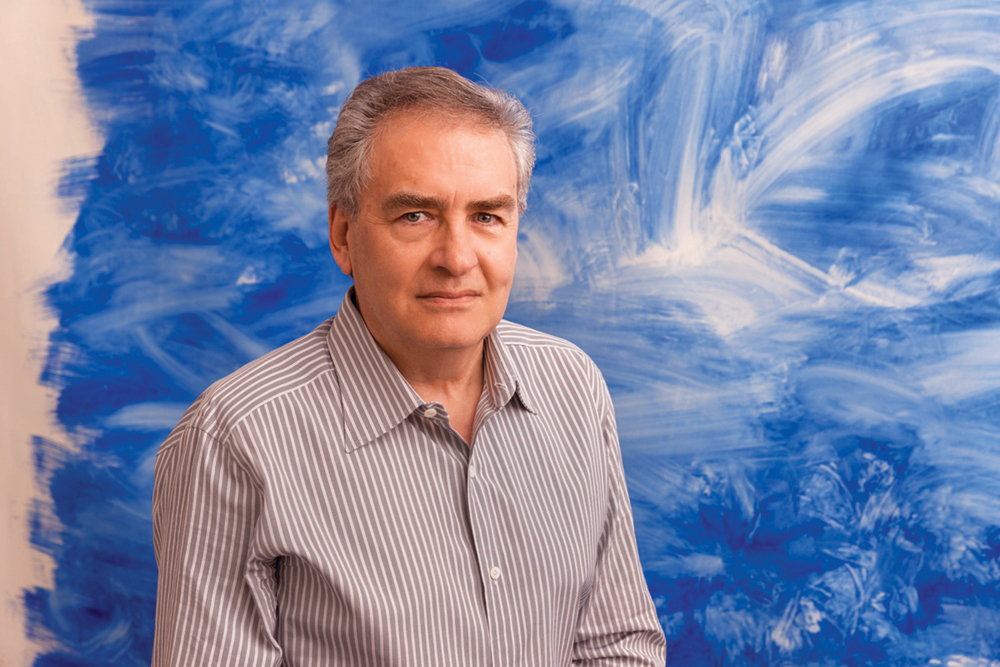

Interview with Juan Dávila

“Our first modernity in Latin America is indigenous, not a discovery in Paris in the 1870s, something happens there that resists academic, scientific and rational thought.”

By Paco Barragán

On the ocassion of his recent solo show “Juan Dávila: Imagen Residual/After Image” at Matucana 100 in Santiago de Chile, we spoke to Juan Dávila (Santiago de Chile, 1946) about some of the themes that have articulated his prolific artistic trajectory like the idea of belonging, nationhood, gender, his relationship to the Chilean avant-garde, Latin America, jouissance and painting. The show not only meant the reencounter of Dávila with the Chilean art scene but also the reencounter of the Chilean art scene with painting as never before so many works of Dávila had been exhibited in Chile.

Paco Barragán - In 1974 you left Chile some months after the Pinochet coup. Since then, you’ve traveled back and forth between Melbourne and Santiago. How was your relationship with the Chilean avant-garde, the so-called Escena de Avanzada?

Juan Dávila - I left Chile after the coup for personal and political reasons, but I kept in contact with the so-called Escena de Avanzada for many years, traveling often between Australia and Chile. I met during the Allende period many of the artists, intellectuals and writers like Eugenio Dittborn, CADA, Lotty Rosenfeld, Diamela Eltit, Carlos Leppe, Raúl Zurita, Arturo Duclos, Nelly Richard and Nicanor Parra involved in that Chilean avant-garde. My first feeling was of great enthusiasm and stimulus-there was a group of creative people in the most difficult circumstances of a military coup. It was a utopian moment and I also assumed-naively-a belonging for me.

Many important artists, mainly the ones aligned with the communist party, were exiled to Europe. This created a heroic reading about them, and the left declared that no art could be produced under a military regime. I reacted against this by trying to make visible overseas the work of artists working in Chile. Australia helped me, and I published via Art & Text Nelly Richard’s Margins and Institutions, financed the magazine Revista de Crítica Cultural and worked trying to obtain visibility for this scene in Australia, London, etc. via biennales, galleries and museum exhibitions.

This romance did not last long, as I began to receive what they ironically call ‘El pago de Chile’ (Chile’s payment). No thanks or friendship. Either you followed their visual approach or you were attacked. The Escena de Avanzada developed a nasty edge, becoming an ambitious, censorious, bullying and psychotic group of holders of the only truth. This process developed slowly and, paradoxically, both the left and the avant-garde in Chile proposed narratives of them being the foundational contemporary art in Chile in the heroic fight against the coup. They had clashing art languages but acted similarly in the exclusion of other ‘non believers’ to be crushed, as many were. It was a sort of hall of mirrors, left/right. Nicanor Parra said: ‘The right and the left united will never be ‘defeated.’

Juan Dávila, The Wurlitzer, 1978, oil on canvas, 77.5” x 83.85.” Courtesy of Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne.

P.B. - The Escena de Avanzada was inspired by European artists like Vostell and Beuys. Their idea was to fuse art and life, favoring more radical formats like conceptual art, minimalism, video and performance. Did their actions have any influence on society during the dictatorship?

J.D. - Regarding the Escena de Avanzada, inspiration was varied. There was the visit to Chile by Vostell, the overseas publications carrying images of performances, art in the city and other conceptual art forms. But there was also the work of people within Chile like Ronald Kay. He published a magazine and an extraordinary book called Del espacio de acá, a fundamental text analyzing the pictorial and photographic discourses in the never-before seen spaces, like South America. One must also see the varied tradition of art making before the coup, good or bad, it was the background of the place. And there were the texts by Derrida, Barthes, Foucault and the European philosophical debates known in some circles, but generally not by the art makers.

Sociologists criticized the Escena de Avanzada as being elitist, obscure and without social reach. This implies art language as being a tool of communication, as something whose efficacy can be confirmed. As far as I can remember, only the work of Lotty Rosenfeld reached the social sphere with her using crosses to alter the painted lines of the roads. This sign ‘+’ became no more deaths, torture. That is to say, it entered the field of communication and it could be measured. I had an experience of such public sphere for art with my image of the liberator Simón Bolívar as a half-caste and feminine, prompting complaints from Venezuela and other Bolivarian countries to the Chilean president. My image of Bolívar appeared as a postcard that I carried out with public funding. What’s new? The press does not read art or nuance. In both cases there was little attention to the actual artwork.

One of the key issues of the Avanzada was the actual use of language. It proposed a language that could obviate the censorship with a hidden text, with a vibration of other meanings against the lineal language of history and the military. A language of disobedience, a language with a seduction and erotically charged, uncontrollable. Your question about influence on society during the dictatorship has a double answer. On the one hand, its influence reaches until today, over 40 years since the coup. On the other, it contained much that cannot be put in everyday words, the utopian dream now betrayed.

But the Avanzada of the early period is not the same as the one during the return to democracy or today in the digital and plastic era. The initial magic disappeared and was replaced by a fixed discourse of ‘art and politics’ as a mantra that crushed many generations that followed. Psychosis, paranoia, control and ambition reared their ugly head. The need to succeed overseas and the dismissive treatment of the next generation of artists created a devastatingly negative cultural life. I speak today thinking of them. This avant-gardism became as official as the discourse of the left. Can I say this as not being an intellectual, an academic or an art historian? This is one of the critical levels for me when trying to demystify the Avanzada. Yes, I can remember and feel and wish for a different narrative.

Juan Dávila, Hysterical Tears, 1979, oil on canvas, 70.07” x 260.4.” Courtesy of Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne.

PAINTING, MALDOROR AND THE BODY

P.B. - You have always been a painter since the very beginning back in the 1970s. But at the time of the Escena de Avanzada, painting was considered old-fashioned, academic and even retrograde, while other disciplines like performance, installation and conceptual art were preferred.

J.D. - There has been a misunderstanding about the Avanzada and painting in some quarters and in the press. At the beginning, the Avanzada was interested in many painters, including myself. I received beautiful texts written by Nelly Richard then. The problem appeared later, not particularly with painting but with any other art expression that did not follow the art/life premises of the avant-garde, the use of the city as a support for art, absolute negativity, conceptual art and intellectual edge. Painting, galleries, museums were the tradition to be avoided. Look at them now!

I also recall later the appearance of a neo-expressionist painting symbolized by the artist Bororo. There was also another group that depicted the city of Santiago. Both used a rough manner, with colors like the dirt, dust and depression of the Chilean air. What is the color of the air today? You tell me. The color of the rejection of these artists was condemnation as fools. What can one say when formalist art reappeared? It was looked at with black contempt.

But there was another side to this. In 1979, I exhibited at CAL gallery in Santiago. The poet Raúl Zurita came to the gallery and masturbated in front of one of the paintings. Artist Lotty Rosenfeld took photos of the performance. Much later, artist Carlos Leppe destroyed one on my paintings and exhibited it at the Tomas Andreu gallery, also in Santiago. How can one think of this love of painting? I can only say that I should have followed the advice: ‘If you want a friend get a dog.’

If I said that cave art is finished it would be in that avant-garde tradition. An artist like Eugenio Dittborn said that he was not a painter, he is someone who prefers printing; Gonzalo Díaz abandoned painting for collage. That was the extent of their folly, but both continue to use the ‘formats’ and spaces where painting is shown. It all is an infantile approach that the press loves: avant-garde versus painting. The issue is quite different: They were the ones that fought censorship and now in turn censor others.

My contention is that both the Avanzada and the traditional left are still stuck in re-writing the local Chilean art history with a nostalgia for the 1970s when they had a vibrant moment. What are their proposals for art in the 21st century? They are just bureaucrat’s talk.

Juan Dávila, Retablo, 1989, oil on canvas, 118.11” x 118.11.” Courtesy of Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne.

P.B. - Let’s talk about your very beginnings in Chile in the 1970s. What triggered your interest in art in general and in painting in particular?

J.D. - How can one begin to answer that? One does not choose parents, social class, place or personality. Not even date of death, perhaps not quite nowadays. I am not a believer in the psychosocial analysis of artworks. Even if I revealed early interests that would not really inform the future artworks. I did read the classics, loved Sophocles, the surrealist manifestos, so what? The burning questions of a young man, the first expressions in art, the repressed materials are not knowable by the artist him or herself. If the artist did say anything rational about his work it would be self-censorship. In an era with no television, looking at bad art reproductions of art was good. Creating imaginary sequences also: Byzantine art, El Greco, Velázquez, Goya, Manet, Ecran magazine, Topaze, Verdejo.

I loved to paint before the 1970s, an enjoyment that does not need explanation. Entering the School of Art at the University of Chile, I discovered a complexity of choices in the so-called ‘real world.’ My choice was to follow my instinct, against the then-prevalent political denunciation or traditional decorative art. A passion for knowledge was not the real thing in the 1970s.

P.B. - All right, but your maternal grandmother, Celia Claro de Willshaw, was related to Breton, so Surrealism was something that very early became common to you.

J.D. - Breton used to send his books to my mother. Reading the Surrealist Manifestos was a revelation for me. I had read Freud as well and was fascinated by the misunderstanding with Breton. Art and the unconscious is still a subject today, alas forgotten by the art for the market, art as spectacle and mindlessness prevalent.

Juan Dávila, The Liberator Simón Bolívar, 1994, oil on canvas, 49.21” x 38.58.” Courtesy of Kalli Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne.

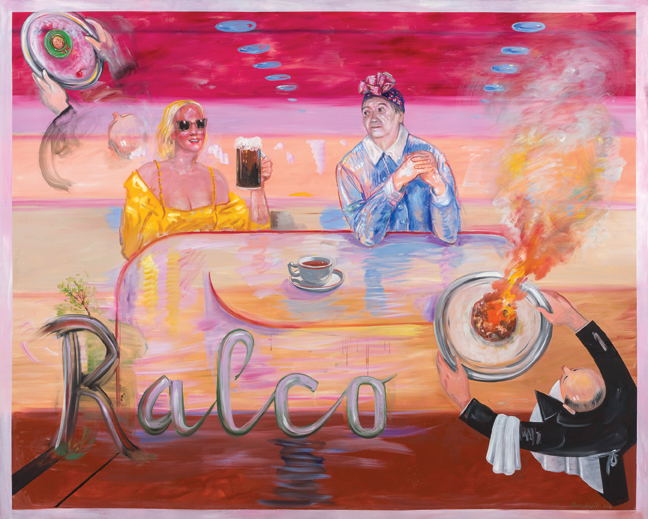

P.B. - From the very beginning, think of works like Nemesis (1976) and The Wurlitzer (1978) to more recent works like Eleleleu (2014), Entitling (2015) and Ralco (2016), the body becomes a site of political struggle. When you take a close look you see bodies that are neither masculine nor feminine but bodies in flux.

J.D. - In the 1970s, I just painted from imagination without the Photoshop approach of today. Realism, distorted geometric spaces, popular art representations led to scenes of eroticism. Nothing new, except that I was not depicting women, men or transsexuals, they were apparently all at once. It just happened. Many criticized me for such images of ‘women.’ In Chile, both the left and the right were misogynous, machista and conservative. In general, readings of images of desire are blocked. Take Bellmer and his doll, it is not a woman, it’s him as a girl.

You ask about Nemesis, a picture painted 40 years ago. Even if I remember what I felt then, why should I express it now? The 21st century has a mania for accountant explanations from the artist. I imagine that it is part of risk management of images. I often get museums asking for a blurb for an artwork. If this was the case with Nemesis I could reply: ‘It is a lizard enamored of a Man/woman.’ Would that suffice and go into the earphones for the public? No.

An Avanzada artist commented to me back then that such pictures had no intelligence. I presume that he spoke from the conceptual art type of intellectualizing. Pre-modern images have another sort of logic, one previous to the rigid computer and digital era, where there is nothing between 0 and 1. I admire Philip Blom’s writing in The Vertigo Years about the technical revolutions that marked the population and culture before World War I. Neurasthenia was then prevalent, a weak, unmanly, tired feeling. Today we have with the digital revolution a ‘normal psychosis,’ or everyday numbness, of consumers in debt living in a virtual barren world where war and money is all. The symbolic life I appeal to in pictures like Nemesis is gone.

Who remembers the Les Chants de Maldoror by Lautréamont? Polymorphous sexuality is ancient and all children know it. For us, the masculine/feminine subject in flux is a great potential for change. The demand for rational explanations must end-desire has no words to explain it. Call me so 20th century!

P.B. - I understand your point, but for me the question is still important because you always offered alternative readings or counter-readings to the official history by depicting the outcasts, emigrants, refugees, transsexuals, aboriginals; in short, society´s anti-heroes. And in this sense I interpret this conceptual anti-heroism connected to a hermaphrodite body, a body neither masculine nor feminine but in flux, like memory. And so your bodies in flux become a metaphor for the alternative bodies and alternative memories, those that have been silenced by power, while the white, patriarchal, hetero-normative body corresponds to official history.

J.D. - I do not have the capacity to work in a clear and condensed way. My way owes a lot to intuition and lack. I would agree in retrospect with your reading, but there is a problem with the idea of a body in flux. It is a construction that tries to name something that cannot be named. It cannot be named because it is ineffable, beyond words, unutterable. Yet it must be represented because it is ineluctable, irresistible.

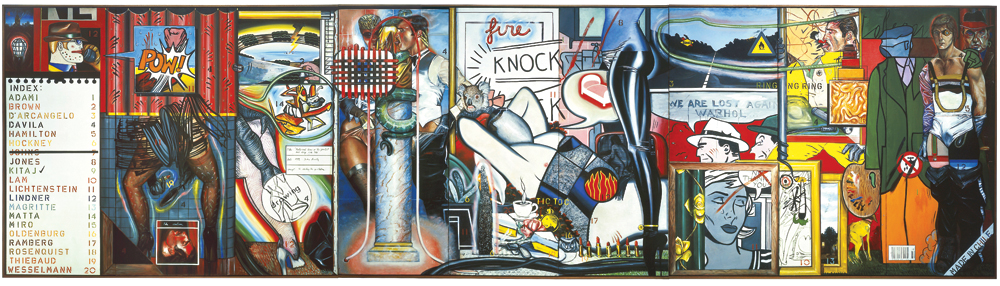

AUSTRALIA, POST-MODERNISM AND THE NOTION OF THE INDIGENOUS

P.B. - You moved to Australia in 1974. It was the time of postmodernism. Australians always had what they call a ‘secondhand experience’ of art. At the end of the 1970s and ‘80s you made large compositions that addressed the discussions about globalism versus regionalism-think of works like Hysterical Tears (1979), Miss Sigmund (1981), Fable of Australian Painting (1982-83), Neo-Pop (1983-85) and many others-in which you challenged this long tradition of repetition and dependency of the Western canon of art and their lineal representation and (sociopolitical imperialism implied with it). In your collages, citation became important, turning them into some kind of archives of visual culture.

J.D. - My interest was to propose an alternative reading of art history, if you like, to play with the idea of belonging. If an artist at the end of the world could redo the art history of the West, getting everything upside down within a painting, confusing styles and dates, mixing them with psychoanalytic issues and other narratives, it would be creation as a poetical act. It would also pose resistance as internal within the creative act. In such matters, like the Google control of all the world’s art and erasing dates, information, stamp size so that we cannot see much, potentiality the artist’s work can be asserted in an act that has no efficiency but is nevertheless asserted when not trying. Contrary to the avant-garde complicity with business, the potentiality to say something or not, to do or not, to write or not carries a potentiality of a poetic act. It is an act that does not depend only on actuality, its potential is also impotency. To stand still, the ambiguity of being and not doing, is also a creative act, which our multinational era despises. We are condemned to accountability, to doing, to explaining. The art scene is full of it. I am sorry, but I forgot the name of the philosopher who poses such dilemmas.

P.B. - Right from the very beginning, your work was very provocative, both to (Australian) society and the art world, and it still maintains this aspect. Elements related to aboriginality, nationhood, war, emigration, social injustice were very present. Think of works like Utopia (1988), Nothing If Not Abnormal (1991), The Medical Examination (1999), Lost Child (1999), The Australian Republic (2000), Election 2001 (2001-02), the Woomera series…

J.D. - I have worked with social subjects, in a sort of narrative painting, comic strip or historical comment. I do not consider myself to be in the so-called ‘transgression’ mode of the avant-garde. Historically, Latin America and Australia were products of violence, genocide and crushing of local culture. That remains present in an artist’s thinking and language. The European rationality and subjectivity we have is tempered by other local forms of thinking and creating life within the digital era. How are we to think about art and politics? It is not a slogan as the Escena de Avanzada in Chile promotes today in a literal form. The specific interest I have is to think about ourselves as a non-identity within the current worldwide system of fixed ideas of nationhood. Nostalgias of the previous challenges to the status quo coming from indigenism, feminism, ethnicity, sexual gender, class does not help in the process. We can be in a constant reaction to new forms of seeing reality and from other perspectives, including, as I have mentioned before, work with the inner resistance, the unutterable instead of utopian myths and demented quasi-religious mantras. Is there identity in such an approach without clear forms? Read the Permanence of the Amorphous, Visual Hypothesis Concerning the Thought, of Rodolfo Kusch.

Panoramic view exhibition “Juan Dávila: Imagen Residual/After Image” at Matucana 100. Photo: Omar Van de Wyngard. Courtesy of Matucana 100, Santiago de Chile.

P.B. - In this sense, and to quote Guy Brett on the occasion of your retrospective in the MCA in Sydney in 2006, you are ‘still concerned with the “repressed contents” of Latin American history and art history. The notion of the “indigenous” and the traumatic event of the Spanish conquest of colonization,’ but also the influence of the Catholic Church and the Baroque. We can experience this in works like Retablo (1989), Mexicanismo (1990), Flower Vendor (1993), Juanito Laguna (1995) and Yarwar Fiesta Sangrienta (1998), just to mention a few.

J.D. - My first recollection of thinking about Latin America in my youth was when I read that Marcel Duchamp invited Frida Kahlo to exhibit in Paris. He placed her work next to craft masks. The exotic and naive Latino was his approach and it lingers on. So much projection we still have over the lost continent. Think of the Metropolitan Museum in New York and its exhibition of Latino splendid ‘treasures.’ But there are serious endeavors, for example in England with Guy Brett and others. One of the most impressive exhibitions I saw was in Antwerp. It compared the Western fantasy of Latin America and the actual art of the place over the centuries. Unfortunately, for publicity purposes, it was called “The Bride of the Sun.”

Within Latin America there has been a similar misinformation about each other. We still have no idea of the art of our neighbors. Romantic indigenism in the 19th century gave way to bombastic social themes in Mexico, then the dark continent idea, the kitsch place, the place as a desired body, etc. I have argued that our first modernity in Latin America is indigenous. It is not a discovery in Paris in the 1870s. Something happens there that resists academic, scientific and rational thought. The liberal ideology has tried forever eugenics there; it doesn’t work. They have contempt for the have nots, but they have a dignity that is not to be crushed. True bonding is possible as a mad love destiny in Latin American art. But the psychotic foreclosure of the place thinks it has won the day. It is our different history.

By now, the West is done with Latin America.

CENSORSHIP, JOUISSANCE AND THE MORAL MEANING OF WILDERNESS

P.B. - Iconoclasm and censorship have always been present in your career. Think of the incident with the work The Liberator Simón Bolívar at the Hayward Gallery in 1994 and the diplomatic incident it unleashed with Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador, but also back then at the 4th Sydney Biennale (1982), with the abortive arrest of the work Stupid as a Painter (1982), and even more recent with the Documenta in 2007.

J.D. - The issue of censorship has followed me, as always the base for it is a ‘scandal’ for something quite outside the artwork. I use humor in art that explains my approach. What would be the use of looking for scandal? It only plays into the official controversy of selling tickets for bums on seats. In Documenta, a cardinal called my work ‘entartete kunst,’ degenerate art, when I painted about Schreber’s fantasy in a Freudian case. The painting Stupid as a Painter literally arrested by the police and placed in a van was a reaction to homosexuality on the behest of a priest addicted to porn. I thought I was painting about women. Simón Bolívar was objected as lesse majeste to the Father of Latin America. Not to mention that he was a half-caste.

Recently, the minister for culture in Chile, Mr. Ottone, censored the work of a Chilean artist for depicting himself masturbating in front of an image of Salvador Allende, the ex-president. This left-right government alongside promoting ‘Saint Allende’ has worked hard to establish the moment of the overthrow of the dictatorship as the foundation of their credibility today. The case is that incompetence, corruption and denial of social programs is not solved by nostalgia. What if the artist masturbated with a green chair?

P.B. - In recent years-I´m thinking of the Moral Meaning of Wilderness (2010) and the After Image series (2014-16)-you addressed concepts like beauty, jouissance and the representation of women and the gaze.

J.D. - We have today a passion for ignorance and hate in culture. Then there is the desire not to know. And we have the wall of language. We cannot assume that our ‘half-said’ art allows us to approach reality. Normal functioning is a lie because the world rests on the suppression of the subject and denial of fantasy. Fundamentalism is the 21st century form of religion, scientific, masculine. Oppose this state of affairs with the question: What does a woman enjoy? “Feminine jouissance”-as Linda Clifton states-”is not wholly occupied with man and even, as it is not, at all occupied with him.” Can we paint ‘without knowing?’ As men, we can try to gaze differently at nature, woman, but we speak with our body and do so unbeknownst to ourselves. Thus we might say more than what we know or are allowed to know.

P.B. - Besides addressing beauty, what is still a taboo in contemporary art, you also started to paint like the Impressionists en plein air, going once again against the grain. The big Wallmapu (2016), which was presented at your solo show at Matucana 100, is a good example of this.

J.D. - Perhaps we could think of Helen Johnson’s argument that an experience of beauty can lead to critical thinking. If we seem lost in a degraded democracy where all that matters are the Masters, we can find an aesthetic guide in a sense of community with an intuition that reaches beyond the limits of rational thought. Thinking and feeling in relation to another explores another dimension in our world without meaning. The artist can make ‘a cut’ in this delusion, changing places with the other.

Philosophical aesthetics values perceptual experience that involves all our capacities in a free play hindered by our emotions. Are we to bring together truth, feeling and play as the only parameters? Are love, fantasy and desire the counterpoint? What does desire aim to?

The current art market aesthetics says that in the object we trust, it won’t betray you. In addiction there is no dissatisfaction, either you have it or not without the need of social link or discourse. The rise of the object is reflected also in speech; we need no metaphors. We are no longer repressed with the victory of pornography. The decline of democracy sings the love of the object that only some can have.

Why would aesthetics matter in this age? How can we put a precise price to it? To paint a landscape en plein air, in front of the thing without technology, is not about the past. It is a call to an oceanic gaze, just because we still can and it cannot be controlled. Moreover, if you think then of the word ‘Wallmapu,’ the lost land of the Mapuches, to the Chilean state developers, you sense the moral element of beauty.

P.B. - We shall finish this conversation with the moral element of beauty then. Thank you for this fruitful exchange.

Paco Barragán is the visual arts curator of Centro Cultural Matucana 100 in Santiago, Chile. He recently curated “Intimate Strangers: Politics as Celebrity, Celebrity as Politics” and “Alfredo Jaar: May 1, 2011″ (Matucana 100, 2015), “Guided Tour: Artist, Museum, Spectator” (MUSAC, Leon, Spain, 2015) and “Erwin Olaf: The Empire of Illusion” (MACRO, Rosario, Argentina, 2015). He is author of The Art to Come (Subastas Siglo XXI, 2002) and The Art Fair Age (CHARTA, 2008).