« Dialogues for a New Millennium

Interview with Marc Bijl

“We live in a new era where images are directly thrown in your face.”

Dutch artist Marc Bijl (1970, Leerdam) is currently presenting a big mid-career retrospective at the Groninger Museum in The Netherlands consisting of a selection of his iconic paintings, sculptures and interventions. Elements such as Modernism, graffiti and nationalism get a conceptual twist in order to portray works that linger between the melancholic, utopian and anarchistic. His mix of high art and popular culture in the manner of a “Bourriaudian” post-producer doesn’t leave anyone indifferent.

By Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán - The show that‘s exhibiting at Groninger Museum in The Netherlands now is titled “Urban Gothic.“ It‘s a kind of mid-career retrospective, your second now after “Arrested Development“ at the Domus Artium (DA2) in Salamanca, Spain, in 2009. But you‘re alive and kickin‘, as the song says. Aren‘t you too young for a mid-career retrospective?

Marc Bijl - Well, if you call it a retrospective you might be right; but since I have also produced new works for these shows one might rather speak of overview exhibitions. I am glad that on both occasions I got the chance to present elder and new works together. Visitors and even myself get to see paths I have taken, decisions I have made; shifting in importance and interests; influences and solutions to deal with certain questions that vary over the years. How else can you bring so many of the works from different times and different locations together? Just great! I only want these kind of shows now.

Marc Bijl working on Dark Afterburner (after Josef Albers), 2012. Courtesy of the artist and Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam.

P.B. - Let‘s talk about the title. Why “Urban Gothic?“

M.B. - I made a short movie with that title. It turned into a video clip as part of a DVD by my former band Götterdämmerung. We used it in the show as the ‘missing link’ between street art and the more conceptual approach of my traditional works (paintings and sculptures). The video itself is about a young Greek girl coming to Berlin to become a star. Unfortunately, she gets run over by a VW driven by a frustrated mid-career artist. Even more unfortunate is the fact that this is semi-autobiographical. It has a sort of dark ‘Himmel über Berlin’ post-punk feel to it. “Urban Gothic” does not so much refer to architecture but more to melancholia and urban landscapes-it fit perfectly as the title for the entire show.

P.B. - But your work has also exhibited a consistent interest in Baroque, Romanticism, Modernism…

M.B. - Yes, the other title I had in mind was “Gothic Modernism” because of its contradictions.

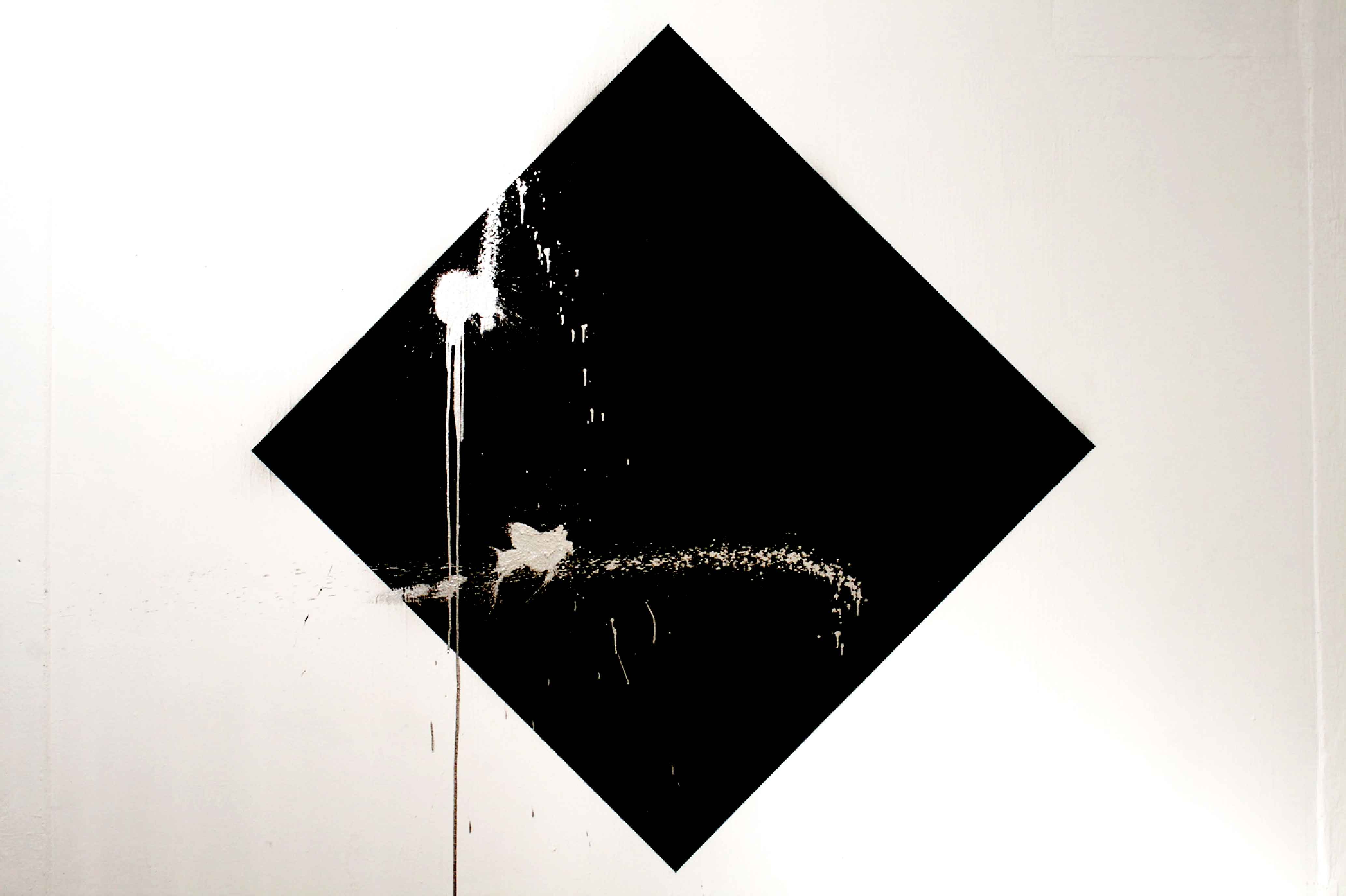

“Marc Bijl. Urban Gothic.” Groninger Museum, The Netherlands (October 6, 2012 – April 1, 2013), exhibition view.

ORIGINALITY, APPROPRIATION AND POST-PRODUCTION

P.B. - Appropriation is a recurrent element in your artistic practice, in which you feed from both popular culture and high art. Is the romantic myth of creating something from scratch, the so-called ‘creatio ex nihilo,’ forever over?

M.B. - Has it ever not been over? Or do you want to talk about religion or politics? It’s history repeating, referring and contextualizing all the time, that is human; it leads to new perspectives in the end. Of course, I also reflect artistically on these appropriation questions, works and approaches artists like Sherrie Levine, Sturtevant, Richard Prince and others have brought to a wider public. For that reason I use radicals like Mondrian and Mark Rothko not as appropriation but as ‘homage.’

More important is that even after 30 to 40 years people still do not really know how to deal with these works. The Olympus of art history has not been climbed and their artistic value is rather often questioned or misunderstood. Appropriation art, as we call it, itself was so very promptly appropriated by critics, curators and collectors that the real debate never really even got started. And even though I do not want to open the Warhol and/or Duchamp files here, it remains questionable how brutal in a way positions were categorized, labeled and put aside as over and done.

Art has always been dealing with the everyday reality, with our daily surrounding, society and contemporary imagery. No matter if you take Medieval, Renaissance or Baroque art production, the question of inspiration, exchange, copying, authorship and transformation has ever and ever again been ventilated-even though different values might have been guiding the answers or solutions. As we speak the discourse on originality, authorship and invention or reinvention is ever ongoing. I am not interested in defining any final statements; instead, I want to keep my eyes, mind and heart open.

P.B. - So you’re suggesting the idea of the artist as DJ and sampler, as post-producer as Nicolas Bourriaud would have put it?

M.B. - Yes, but make no mistake: Creativity and inspiration never lead to a complete new idea; art is not a ‘tabula rasa’-its very nature is that it derives from previous ideas, utopias, concepts and mistakes. So, referring and redefining existing art (works) is not ‘sampling’ or ‘mixing.’ I would rather refer to music and musicians and rock ‘n roll bands rather than samples and DJs.

P.B. - Some people say your work is very direct, which I think is a superficial comment. There are many layers, from pop culture to high art, which are not always very visible, but it allows different audiences to engage at different levels. It reminds me of the sophisticated meta-levels of Lady Gaga.

M.B. - I like Lady Gaga, although I have not one record of her, but she seems to be more sophisticated, authentic and honestly theatrical than many other ’serious’ pop artists who don’t take risks and are created by management and record companies.

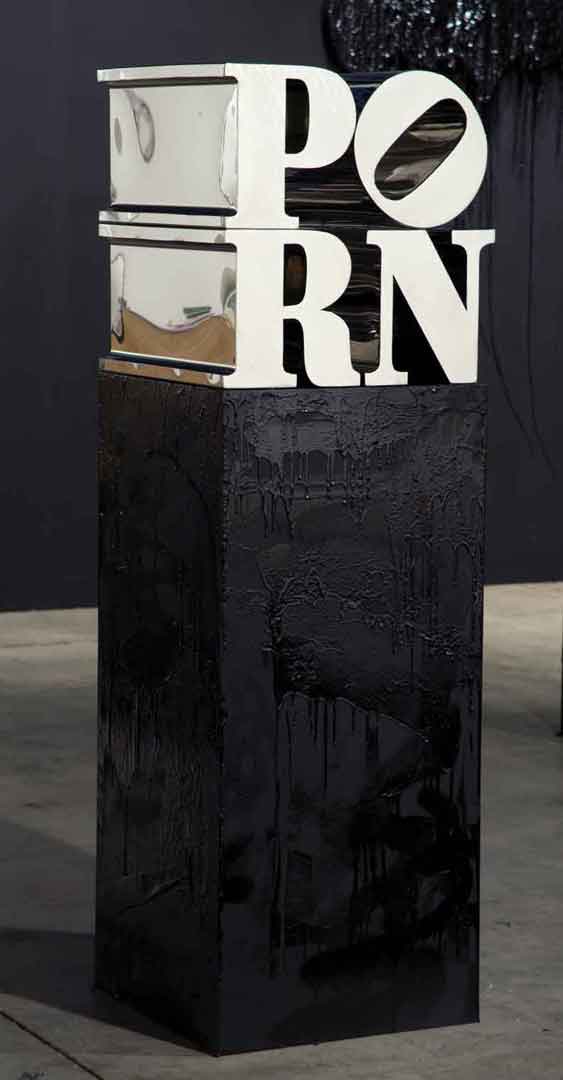

P.B. -The work PORN, for example, refers to Robert Indiana and General Idea and the 1960s protest culture. You did several versions. Is your piece more than post-modern irony?

M.B. - The very idea was indeed another label for our time, as we had in the 1960s (by accident) created by Robert Indiana with the LOVE logo. It perfectly summed up the swinging 1960s and early ’70s. General Idea did a version with AIDS which was a label for the ’80s. I was in Künstlerhaus Bethanien in 2001 and we were all witness of the 9/11 attacks, and this influenced my practice. I was intrigued by the idea that we enter a new era, a society where images are directly thrown in your face. You have to protect yourself against those images and influences of violence, war and social media. There is an information ‘porn’ that was the original thought, so yes, I made several versions of this label of our times.

MONDRIAN AS ABSTRACT ACTIVIST

P.B. -In “Urban Gothic“ you go back to painting again. The series “Abstract Activism“ engages with painting’s abstraction and its pureness. How do we have to understand abstraction here and activism?

M.B. - It is more about radicalism, where political radicals use radical tactics to get their agenda noticed. Artists like Mondrian slowly went radical in an artistic sense. For me art is about moving forward, sometimes getting lost, getting radical and making bold statements. For now I have decided to take these traditional art forms like painting and sculpture in a more serious account. In such a way that activism as an artistic form will no longer feature adolescent punk images. In a way, I have matured and see radical activism in abstract art. It’s not a sudden decision-my work has grown in that direction. Instead of using symbols and logos I try to tell the same story about power structures and counterculture in an abstract way. Why? Because as an artist I like to surprise myself again and again.

Marc Bijl, Abstract Activism Wallpainting (after Mondrian), 2010. Courtesy Upstream Gallery, Amsterdam

P.B. -In this show Mondrian plays an important role. There is respect but also a demystifying attitude. For example, the wall printout seems like an ironic resignification of modernist dogmas.

M.B. - Yes, there are two aspects to the story: It is indeed an homage but also a reference to graffiti art, which obviously did not go through a period of modernity-but also the freaky idea that Mondrian is not abstract anymore. Did you ever think about how radically well-known abstract images in art can be? Like an icon.

P.B. - Well, for me, Mondrian has never been abstract as it has always referred to objective or referential imagery. Even his latest works like Broadway Boogie Woogie or the unfinished New York City 3 refer to urban cityscapes. This can also be said of Kandinksy, Rothko and many other abstract painters who in the end refer to landscapes. So I can’t share your opinion about the radicalness of abstract art. We should also bear in mind how abstractionism was manipulated by the CIA. And, there has not been after Guernica a single work that has had the same politic and universal importance. And as for graffiti, I think that artists such as Shepard Fairey and Banksy are in the end quite established and musealized.

M.B. - Yeah right, Mondrian was created by the CIA! C’mon! It was, of course, a reference to existing patterns and structures like Malevich’s Black Square; nevertheless, their impact on what art can be in the age of reproduction is phenomenal-beyond recognition and with imagery of the unknown, the abstract. And it still is. But you are right that politics could be a good promoter, but it doesn’t mean that abstract artistic freedom came from U.S. politics. As you said, Kandinsky and Malevich and Mondrian were there before.

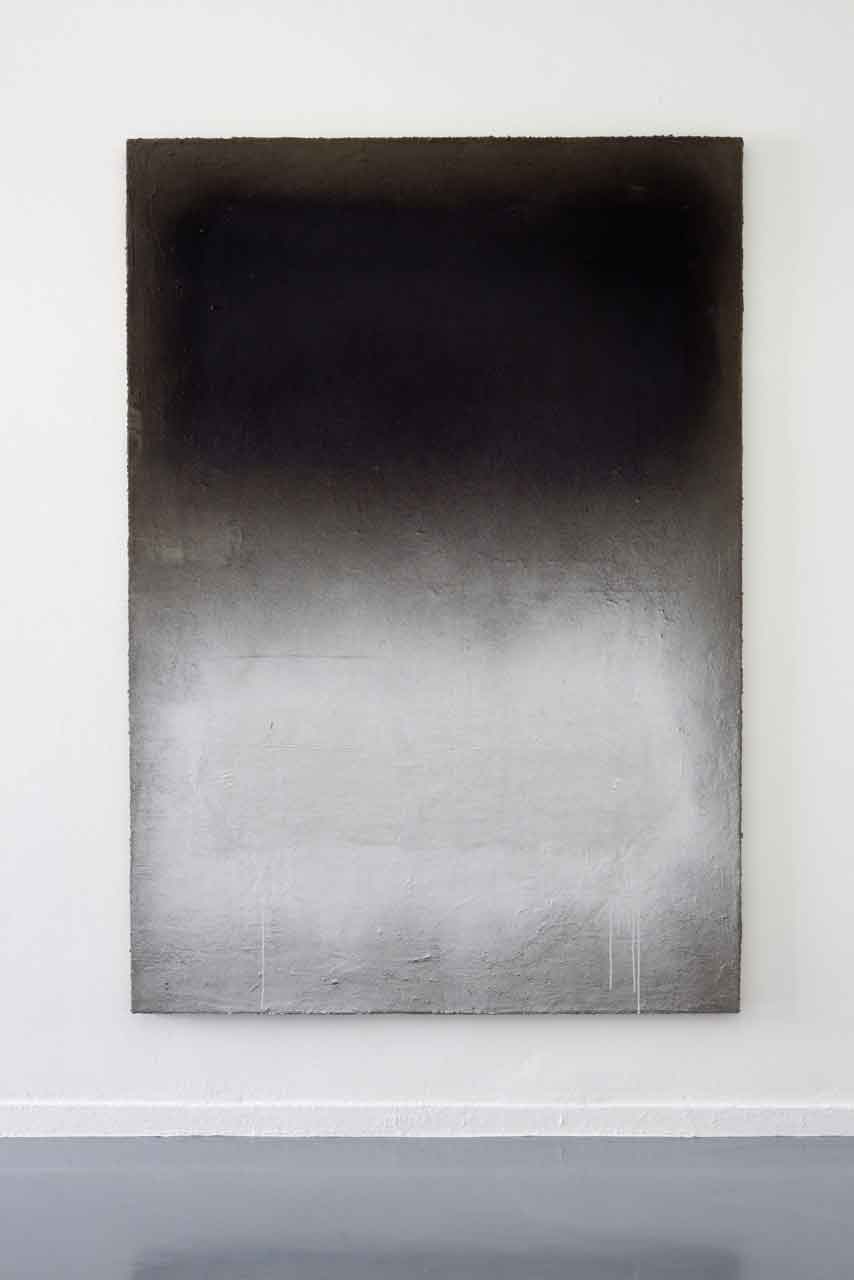

Marc Bijl, Afterburner (after Mark Rothko), 2011, canvas, spraypaint, plaster. Courtesy Reinhard Hauff, Stuttgart.

P.B. -The CIA used American Abstract Expressionism as an ideological tool. Pollock, Rothko, de Kooning and the like were of course influenced by Malevich, Mondrian, Picasso and so on. As usual, you use national symbols: The lion coat of arms, and especially Queen Beatrix. Politics seems to have become a matter of sheer populism in which the citizen has nothing to say.

M.B. - Yes, Queen Beatrix is an icon of power but still not populist because she does not need to win the votes of the people in order to defend her next election because she has a job for life.

Marc Bijl, The Fundaments of Painting (Influential Dutch Thinkers: Beatrix), 2007, silver paint and spray paint on canvas. Courtesy Upstream Gallery Amsterdam.

P.B. - But the use of Beatrix is the use of a very kitschy symbol, like politics that is also very kitschy. So, both politics and the monarchy function on a kitschy level, representing complex issues in a simplified manner like great performers who really seem to care about their citizens and are giving them the idea that they really have a say.

M.B. - I could not agree more.

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust in New York and recently curated “The End of History…and the Return of History Painting” (MMKA, The Netherlands, 2011) and “¡Patria o Libertad!” (COBRA Museum, Amsterdam, 2011). He is co-editor of When a Painting Moves…Something Must Be Rotten! (2011) and the author of The Art Fair Age (2008), both published by Charta.