« Face to Face

Interview with Martha Rosler

“Feminism is a viewpoint that demands a rethinking of questions of power in society and thus has undeniable potency.”

By Paco Barragán

Martha Rosler is a prolific American artist and writer. Her works range from photo-text to video, performance and installation. At the center of her artistic practice are sociopolitical concerns related to, among others, women’s place in society, art and its power structures, post-modernism and corporate media. We exchanged ideas with Rosler about these topics, social media and her upcoming ‘event’ at MoMA.

Paco Barragán - Let’s start with your article “Lookers, Buyers, Dealers, and Makers: Thoughts on Audience,” first published in 1979, and of which you wrote a post-scriptum in 1984. The ‘audience’ you refer to has been a much talked about topic since the 1960s. Do you think there has been a significant change or development in the relationship between the art world and its audience?

Martha Rosler - The art world itself has expanded greatly, and the role of art and culture has become more prominent, especially in the lives of the middle-class urban dwellers. The end of High Modernism has meant a less adversarial role between viewers and the cognoscenti, by which I simply mean those who are educated about art. Art has also swelled to encompass all kinds of practices that take place in other corners of culture, like schooling and farming.

ART CRITICISM AND AUDIENCES

P.B. - For some years we witnessed new critical thinking regarding the position and function of the artistic institution, which crystallized in the so-called New Institutionalism, a sociological perspective on institutions and how they interact with and affect society and the individual. Like institutional critique initiated by conceptual art, New Institutionalism also hoped to transform museums and provide a more democratic relationship with audiences. You have engaged with this topic both from an artistic as well as an art-critic point of view. How do you see this right now?

M.R. - A work of mine from the late 1980s, a three-show cycle called If You Lived Here…, is considered an early spur to New Institutionalism, but I have never warmed to the concept. My opinions on the pedagogical function of the art institution have remained in a state of suspension. Museums are certainly more approachable-they have gone far to make themselves seem like friendly and desirable places to visit by adding galas for the well-heeled, dance parties for the young, and activity days for the youngsters. But there is little democratic about museums. They’re still run by upper management, in conjunction with trustees and donors, and are in some degree of thrall to municipalities and elected representatives. This is not democracy. What I am uncertain about is not all these overlapping structures but the effects of the imperative toward public education, and public service, which will very likely lean toward stifling critical art.

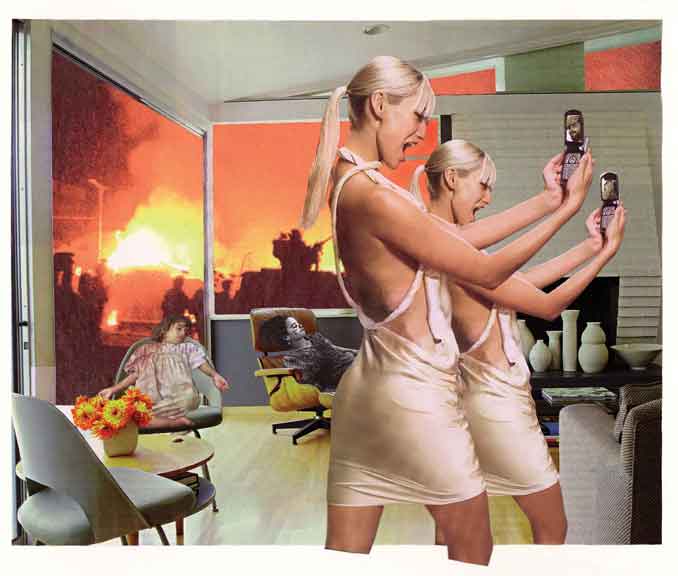

Martha Rosler, Red Stripe Kitchen, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967-1972

P.B. - Is social class still the most important marker in terms of art audiences? It seems that high culture is still the domain of the bourgeoisie and those in the upper class who have access, as well as some members of the middle class who do not have social or financial capital but do have intellectual capital-think of artists, writers and curators, for example.

M.R. - I hardly think social class has diminished in respect to the intellectual ownership of art. But people in the mass audience, people of less elite social status, are now, as I suggested earlier, more familiar with art and the art world. But of course the intelligentsia, as mentioned earlier, are naturally at the center of the art audience-one might even say art community, such as it is. They help form the universe of discourse of art.

P.B. - I do observe one big change: the shift from the combination dealer-art critic toward the dealer-collector, and with it a diminishing critical discourse that affects the quality of exhibitions and the kind of art being sold, which I understand is hopelessly kitsch-easy identifiable, nostalgic, pastiche-like, nicely realist and hardly critical. I’m especially thinking of artists such as Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons, but also painters such as Gerhard Richter and Neo Rauch. What is your opinion about the position of the art critic?

M.R. - The best critics are mostly young and mostly publish online. By and large they can’t make a living from the writing, and often they don’t plan to. The rest of the critical corps seems tired. One of the most widely followed American mass-journalist art critics became a judge on an art reality show. I agree with your characterization of the diminution of the role of the critic, and the elevation of the role of the collector, especially the very rich ones like Eli Broad and before him Charles Saatchi, to name just two; I think, however, the magazines are an important link in the transmission and value and have only increased in importance. Criticality seems superfluous when sales are at issue. I think the U.S. is worse in this regard than Europe, where curators often continue to have a strong idea about the need for critical engagement through art.

FEMINISM, POST-MODERNISM AND MEDIA SOCIETY

P.B. - Your work has related to women’s and feminist issues, and even your anti-war oeuvre, which is more known, takes off from this angle. How has feminism influenced you, and can you talk about a seminal work such as Semiotics of the Kitchen?

M.R. - Feminism is a central angle in all my work; it does not replace or supplant other considerations. Feminism is a world view, or a great factor in such a perspective. It is a viewpoint that demands a rethinking of questions of power in society and thus has undeniable potency. Semiotics of the Kitchen, a sort of bizarrely humorous six-minute black-and-white video from December 1974 (dated 1975), was one part of a large body of work in several media that I had been doing taking on questions of women, society, and art through the medium of food and the culture of food preparation and consumption. The video is ‘a lexicon of rage and frustration’ produced through a noisy and slightly unruly alphabetic demonstration of some hand tools in the traditional kitchen. Another, earlier video which centers on food production and consumption was A Budding Gourmet, and a postcard series I produced a couple of years earlier can be found collected as Service: A Trilogy on Colonization, three first-person narratives of women in different social locations, also with respect to the preparation and consumption of food. A Gourmet Experience is a complex installation and performance I did about those matters in 1973 as my M.F.A. thesis exhibition, and back then I wrote a book, as yet unpublished, about food. So Semiotics of the Kitchen is not a one-off on the subject of women and food.

P.B. - If we look at art schools, M.F.A. programs and museum audiences we encounter an enormous contradiction: While the majority involved in those are women, in museum shows and jobs especially they are totally underrepresented. What strategies can female artists develop to respond to the still male-dominated, patriarchal art world?

M.R. - I am not sure this is a contradiction. Academe is fine with taking women’s money for training-back in the day, art schools were often a good place to park genteel girls, and so is the study of art history and the lower ranks of the curatorial hierarchy. Women artists can and have and continue to set up galleries, exhibitions, magazines and websites irrespective of institutional embrace and simultaneously to agitate about the underrepresentation of women in art and in museum hierarchies. See the actions and the posters put out by the fabulous Guerrilla Girls.

P.B. -The concept of ‘post-feminism’ was coined some years ago and seems to be more flexible, even embracing other causes like the queer and trans movements. I think young women have a kind of phobia about being labeled ‘feminist,’ but does this mean that the empowering of women in the public sphere has retreated?

M.R. - I don’t find post-feminism to be a particularly useful concept in that it suggests the surmounting of the problems you have just outlined in your previous question. Women don’t want to be labeled feminist, in part because for many such a label is feared as messing up their chances to be either loved in private or exhibited in public. In any case, though, I think it’s tough to accept a label from your mother’s generation. It suggests, if nothing else, a long slog. But every decade or so new young women find to their surprise that they are in fact feminists and don’t at all object to being labeled as such. I think it’s a mistake to see post-feminism as a useful term that allows for the inclusion of queer and transgender identities; there is certainly a vibrant expanded, gender-related congeries of movements, but feminism persists.

P.B. - Postmodernism was the result or projection of the crisis of modernism and marked the shift from a text-based to a visual-based society. Not only you, but also artists such as Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger are part of this ‘image’ movement. I think this enabled a new way of speaking to art, economic and politic powers. What is your opinion?

M.R. - It’s certainly true that images are moving center stage, especially in corporate propaganda, that is advertising, and pictures not only provoke or anchor desire, they communicate across linguistic barriers. Also, photographic technologies are now ubiquitous, thanks especially to cell phones, many of which have quite respectable cameras built in. But what, after all, does it mean to characterize us as an ‘image society?’ Are there images anywhere without texts available for our understanding? I doubt that. We might want to consult Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, in which he points out that the ’spectacle’ is the representation of the social relations of the means of production in advanced capitalist economies. Postmodernism in art was also a recognition that meaning was slippery and that ’second nature,’ which we may handily think of as the culture that Debord was writing about, was more essential to those relations of production than nature, the natural world. We may also think of postmodernism as an acknowledgement of a shift in late capitalism from industrial production to financial flows and neoliberalism, perhaps to deal with the falling rate of profit, and from economic localism to globalism. It has become unfashionable to call oneself a postmodernist in art at present, and in literature it seems to also have been a passing phase, filling in for that moment in which, as Lyotard termed it, the grands récits, or grand narratives, of social telos were proving to be bankrupt. But history has not, in fact, ended, nor has the boom-and-bust cycle of capitalism, and thus we see a resurgence of anti-capitalist perspectives, and thus of those “grands récits.”

THE WAR IN OUR LIVING ROOMS

P.B. - In this sense, one of your signature works-if I may say so-is House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home. How did this work come about? Since then the media and war have become recurrent concerns in your work.

M.R. - I was looking for a way to express, in public fashion, my opposition to a war that seemed to be brought to us in the living room, on TV, and which posited a ‘here’ and a ‘there,’ ici et ailleurs. I had been using the montage form to provide a collision within a frame of things we think about when we unconsciously position women as, essentially, home appliances and passive objects of desire, and it occurred to me that I should make anti-war flyers in the form of montaged tableaux drawn from mass picture magazines. I wound up making 20 of them over a period of years, and they acquired that series title, House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home. I was very interested in the idea of identification and non-identification with characters in a narrative and had tried several ways to provoke the viewer’s sense of the uncanny, in order to enliven that issue. I thought of these works as ‘not art’ and refused invitations to show them in art institutions, but as Allan Kaprow pointed out a bit later, non-art always becomes art-art eventually and is inducted into the temple. These works entered the art world initially through reproduction in Artforum.

P.B. - With the supposed nuclear weapons in the hands of Iraq that never materialized and the death of Osama Bin Laden without any evidence of the corpse, how can we interpret critically the concept of the real or the truth, or do we just accept whatever governments say?

M.R. - A false choice if I ever saw one. We use our intelligence to determine what evidence there is for the claims of persons and of the state. Like any good detectives, we ascertain motive and opportunity in the commission of what we suspect are international crimes. Gullibility is not uniformly spread throughout the layers of society, and people are skeptical when claims made run counter to their perceived interests.

P.B. - You’re very active in social media, especially Facebook. Social media give the idea of participation and democracy, but in the end the communication keeps being top-down, and except for some ‘likes’ or comments, neither institutions nor magazines hardly ever answer on the net. There is no such thing as citizen journalism for now. What are your ideas about this?

M.R. - That is a strangely totalizing picture of a complex channel of communication; there is a good reason for attributing some of the rapidity of mobilizations in the so-called Arab Spring to the availability of social media. People who use them are not trying to communicate with those in power but among themselves. It has been very useful in organizing activists-that much should be obvious, I think. Citizen journalism is precisely what drives the many blogs and ephemeral print publications I read.

P.B. - Finally, you’re going to have a show at MoMA. I know you don’t like to give away details beforehand, but can you tell us a little bit about it?

M.R. - It’s not really a show but ‘an event,’ a participatory installation and performance. I don’t have any problem with discussing the details. I am holding a gigantic garage sale in the atrium of the museum-a garage sale is a great, ritualized American institution, a way for private people and families in small towns and suburbs to recoup some financial value from their discarded commodities and for their neighbors to find something of value at a low price. I began running garage sales in art venues in 1973 in California. The work at MoMA is called Meta-Monumental Garage Sale. Look for it in the latter half of November of this year.

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust in New York. He recently curated “The End of History—and the Return of History Painting” (MMKA, The Netherlands, 2011) and “¡Patria o Libertad!” (COBRA Museum, Amsterdam, 2011). He is co-editor of When a Painting Moves…Something Must Be Rotten! (2011) and the author of The Art Fair Age (2008), both published by CHARTA.