« Features

Interview with Martin Soto Climent

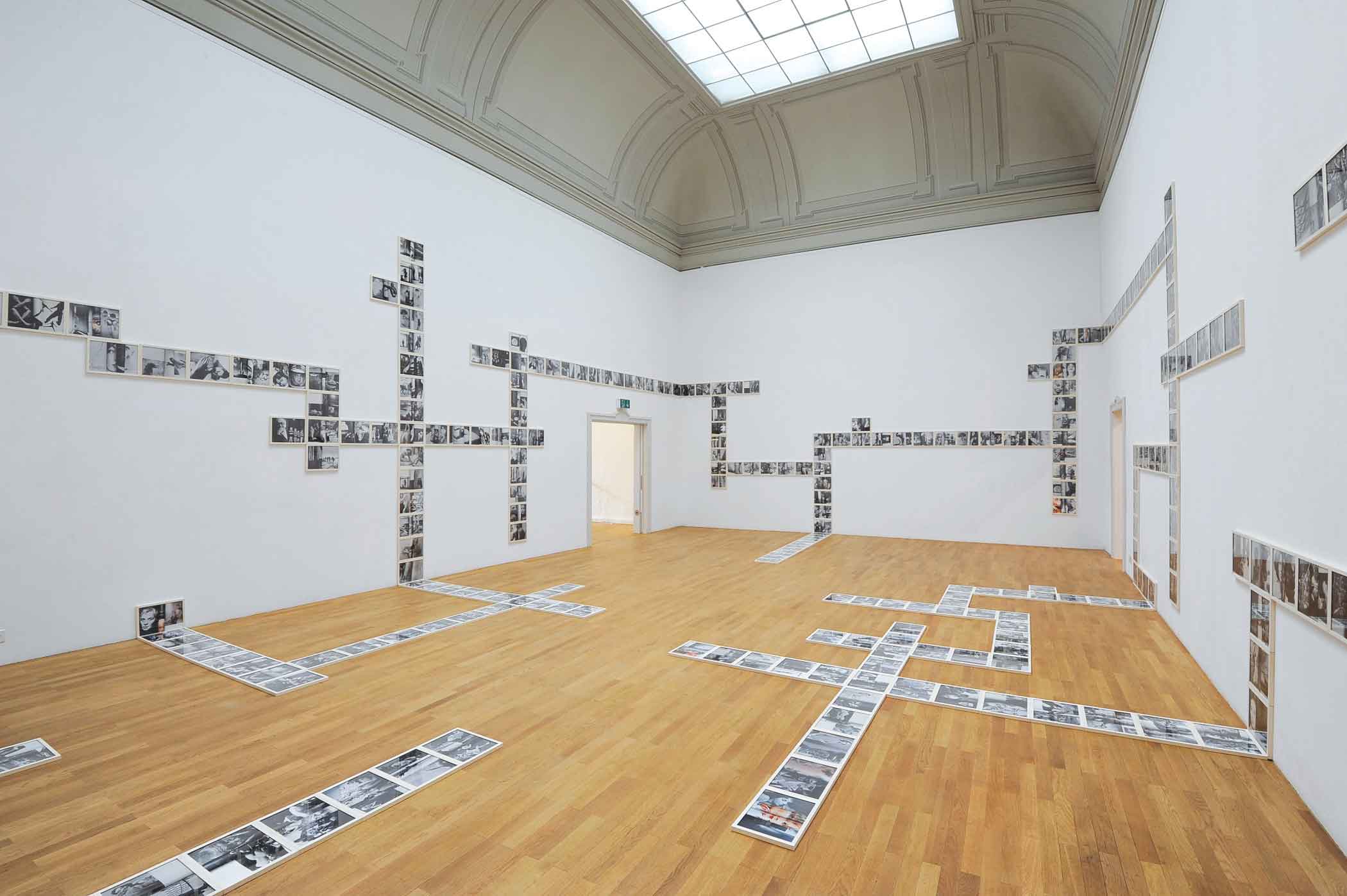

Martin Soto Climent, The Equation of Desire, 2012, installation view, Kunsthalle Winterthur. Photo: Christian Schwager. Courtesy Kunsthalle Winterthur

“I like to disappear; and I do this for my own pleasure of existence.“

Martin Soto Climent, who lives and works in Mexico City, grew up in the countryside outside the suburbs of that burgeoning metropolis. His parents and uncles were successful as industrial designers, but less so as artists. Thus, art was introduced to Soto Climent as something that is done for oneself, free from formats or expectations of commercial success. After studying industrial design, a kind of second life started when he was 24: Returning from a trip to Europe, he ended a long-term relationship and decided not to become a designer. The collapse of his previous life turned into the beginning of something else-a life dedicated to objects and form. The question of whether he had created art was answered in 2006, when by coincidence he met a gallerist from New York. After a studio visit, Soto Climent was asked to present some of his work at Art Basel, and then it all happened very quickly.

By Oliver Kielmayer

CONTEMPLATION INSTEAD OF PRODUCTION

Oliver Kielmayer - In your installations you mostly work with things that you find in a given context; with a minimal gesture you turn them into something amazing, and then you just put them back where they came from. Moreover, you never destroy things, so all together, it sounds like a very ecological way of production.

Martin Soto Climent - The word ‘ecology’ has been abused a lot in the last 30 years, but as a logic of integrating into a system that we are part of, it’s still fundamental. Western civilizations tend to see nature as something exterior to human beings, but actually we are deeply inside of it. We are nature; we are part of its logic, and if we damage something, we damage in the end ourselves.

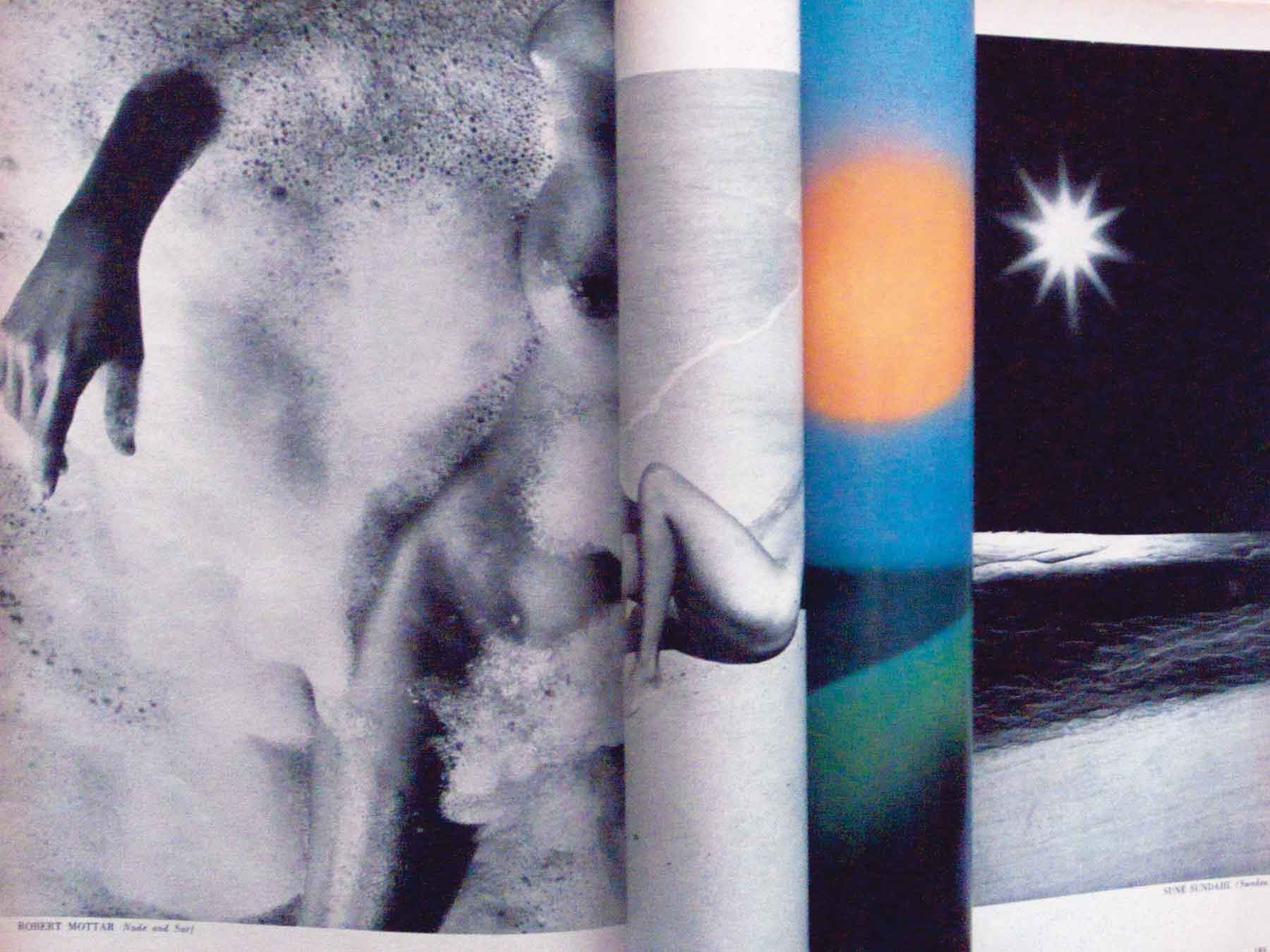

Martin Soto Climent, The Equation of Desire (February 29), 2012, inkjet on cotton paper 9.44“ x 12.6“. Courtesy Kunsthalle Winterthur.

O.K. - A friend of mine once said that Mexican artists often sit in the studio without producing anything, but all of a sudden they come up with a found object, slightly modified but very charming. I can recognize this strategy in your work, and it‘s very much based on contemplation.

M.S.C. - Yes, I contemplate a lot. I actually don’t like work, I think it’s insane. I do like physical labor in order to survive, but repetitive work in the sense of producing thousands of the same is sick. My work is a means to criticize that. This is crucial, because if I only say, ‘Work is sick,’ it doesn’t mean anything; I must prove it. And the only way to prove my own logic and different way of thinking is by my work.

O.K. - A visitor could easily reproduce most of the pieces in your shows. Of course, he wouldn‘t get a signed artwork but would still have the moment. Do you like this idea?

M.S.C. - Absolutely, it’s what I like the most. I know that I play a role within the market, but it’s how I can sabotage it. I do things that could be done by anybody else, and maybe they would do it even in a much better and crazier way!

Martin Soto Climent, Blinds, 2009, installation view, Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen. Courtesy T293 Gallery.

O.K. - In your works you show surprising aspects of objects and things that we normally don‘t see. Thus, they turn into metaphors for hidden potential and beauty in the surrounding world. Do you ever stop seeing things?

M.S.C. - No, never. That’s also why I am so tired every night. Especially when I go on a vacation I get stimulated because I see different things. I just cannot do anything else, I’m a very limited person in that sense. But it’s beautiful and one of the most amazing parts of my work: It’s not about what I want but about what reality offers me. It’s not about forcing to be someone else, but trying to understand a logic, which in the end is also inside of myself.

A FUNDAMENTAL FORCE CALLED DESIRE

O.K. - In your most recent work The Equation of Desire you work on a scale previously unseen, not only in the sense of space, but also content. To reflect the essential questions of human life through your own emotional experience is more than a challenge; it‘s extremely daring-if not mad.

M.S.C. - I must admit it’s a crazy thing to do in our time. But in the beginning it was a very intimate process. I was doing it for myself. I remember when once folding the pages, I suddenly had the idea that I could go large scale, because it’s a never-ending process; you can create as many combinations as you want. On the other hand, all my works follow a set of philosophical questions about life and the sense of the human being. I always wanted to talk about it in a more comprehensive way, so this was exactly the right structure and frame for all the folding.

O.K. - What about the diagrams linked to the work? How are they embedded into the production process?

M.S.C. - The diagrams started many years before. I do a lot of drawing, and I do these diagrams for all my shows. In the one for The Equation of Desire you see something like an onion with a series of layers. I tried to talk about things in the most essential way. From my point of view art has to be essential-or existential, so to speak. It makes sense when it adds up to culture, when it really creates culture. It has to be a universal discourse in a way, because everybody is the addressee.

CREATION WITHOUT DESTRUCTION

O.K. - When did you play for the first time with magazines in the way of rolling different pages into each other?

M.S.C. - I had been doing this kind of unification of forms for many years in a very easy and playful way, so for me it was a natural thing to do. The first work I did with rolling up pages was The Nine Dancers in 2007, but first experiments maybe date back to 2003.

O.K. - Most people would wonder why, since there are so many of these magazines, you didn’t destroy some of them in favor of your own work and throw them away? There must have been a point where you felt tempted because folding or destroying something would have led to an amazing result.

M.S.C. - I had to develop my own idea of freedom to cope with these things. It’s a problem that art and society in general have lived with for almost a century now. If you follow the concept of freedom as understood in the 20th century, it suggests you can do whatever you want; we are liberated and live in a free society. But nobody is totally free. The only freedom we have is to put our own limits. I have defined my own limits, and within these limits I enjoy a lot of room to move. Having limits is a fantastic thing because it gives you structure, and we really don’t have to destroy in order to express essential things.

Martin Soto Climent, La Alcoba Doble, 2012, installation view at T293, Naples. Courtesy T293 Gallery.

LOGICS, ETHICS AND AESTHETICS

O.K. - What is the reason you used vintage copies of the magazine Photography Annual?

M.S.C. - My relation to this magazine is very natural, because my grandfather used to buy it in the 1950s. I grew up looking at these images-they became a natural part of my imagination. The magazines were extremely well done, and the quality of the images is amazing. Also, they are interesting because they represent a post-war moment in the 1950s up to the mid-1970s. In the 1980s, the aesthetics of the magazines changed, and then they disappeared. The image in the 1980s becomes faked, produced in a way, highly effective in the sense of a special effect. I wasn’t looking for nostalgia, but I like the moment of honesty and innocence in the pictures.

O.K. - The pictures of The Equation of Desire are very physical. I also noticed that in the first half there are a lot of female characters, whereas later male characters become more dominant.

M.S.C. - The source material is very physical, and it’s exactly what I like so much about it; there is a strong presence of the human body. The usage of the magazines, the folding of their pages, is also a very physical performance. If you look at the work as a novel, there are two main characters or opposite energies: It’s about black and white, life and death, male and female. But male and female not so much in the sense of man and woman, but more like yin and yang. I use them as chapters, but chapters like the female part of being a man and the male part of being a woman and how they mix. In the installation this becomes clearer: The female energy has a line and meets a male energy, and both transform into something new. Both forces are following and challenging each other, desiring and seducing each other. The woman is the first energy; she gives birth to life. Whereas the female energy goes more to the internal, the male goes more outside. I see my own work as a result of female energy, because it’s not about transformation or damage or penetration. I think we should become a more female society-less damaging, penetrating and destroying, but more contemplative, because we don’t understand things if we manipulate and abuse them.

O.K. - Comprising 366 pictures, The Equation of Desire obviously corresponds to the number of days in one year-a leap year, to be more precise. What is the relation between the pictures and their specific dates? And how was this relation made? I don‘t suppose, for example, that October 10 was missing at a certain point and you had to think about a picture that could become this day.

M.S.C. - It was a very open creative process. There was not the one and only way to find a result, it was more like coming back to things over and over again. After playing with so many images you get used to a certain rhythm. But it was not created like taking a thousand pictures followed by a selection, or saying, ‘Today I’m doing September 2nd.’ Of course, when an image popped up that obviously worked for a different chapter or month, I accepted this. Most important was my mood; you just cannot work with such a quantity of pictures in a rational way. It’s like putting oneself into a kind of resonance, and if the image has the same resonance, it works.

Oliver Kielmayer has been the director of the Kunsthalle Winterthur since 2006. He teaches art history at F+F School for Art and Media Design in Zurich and in 2005 was co-curator of the International Biennale of Contemporary Art in Prague. Some of his recent books include Meeting Köken Ergun (2011), The Telephone Book Special Edition (2010) and Aggression (2008), all published by Kunsthalle Winterthur.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.