« Dialogues for a New Millennium

Interview with Patrick Hamilton

“I think of simple forms, formal economic solutions, but using elements that already carry a very important social and symbolic burden.”

“I think of simple forms, formal economic solutions, but using elements that already carry a very important social and symbolic burden.”

Chilean artist Patrick Hamilton has been living in Madrid since 2014. His prolific artistic trajectory started in the mid-1990s in Santiago de Chile, where he also oversaw a successful artist-run gallery called González y González. I looked him up in his house-studio in Chueca and reviewed with him some of the key topics that have articulated his artistic practice and are mainly related to the neo-liberal Chile of Pinochet and his sociopolitical legacy. Hamilton’s work mixes concept and form in a very personal way, creating something we might refer to as “political minimalism.”

BY PACO BARRAGÁN

Paco Barragán - You studied at the Universidad de Chile. When I lived in Chile, I remember people use to study either at the Universidad de Chile or the Universidad Católica. Are there differences in their artistic formation? Or simply put: Why did you choose the Universidad de Chile?

Patrick Hamilton - The truth is that I first went to study arts at the University of Arts and Social Sciences (ARCIS), which at that time was by far the art school that best taught neo-avant-gardist artistic practices. It was a private university closely linked to the left in several ways, but in particular the School of Art promoted a critical-deconstructive vision of both artistic and theoretical languages. At that time, from 1994 to 1996, I was fortunate to be a student and take workshops with Nelly Richard, Guillermo Machuca, Sergio Rojas, Carlos Pérez Villalobos, Virgina Errazuriz, Fernando Undurraga, Francesco Brugnoli-people with a complex vision and criticism of art and with a very high level. Then I moved to the Art School of the University of Chile where I kept practically the same professors, in addition to Pablo Oyarzún, an authority on philosophy in Chile and Latin America. In short, it was an intellectual universe that today I look at with a lot of nostalgia. To answer your question, I believe that the formation at that time in the Art School of La Católica was much more precarious in theoretical terms, although due to the material conditions of the school (vastly richer than the University of Chile and the ARCIS) there was more access to information-they were subscribed to art magazines such as Artforum, Art in America, Lápiz, and so on-and the students of that school were ‘more informed,’ if you like, but instead the “ARCIS-la Chile” were more theoretical, more read. We do well to recall that at that time there was no Internet. In this sense, I believe I am one of the last generations of artists that studied without Internet.

P.B. - Chile, and in particular the city of Santiago, are important references in your artistic practice. In 2014 you moved to Madrid. What motivated this move?

P.H. - Simply because my wife was given a job at the Embassy of Chile in Spain, but her contract ended some months ago and we decided to stay. So, I did not choose Madrid, but I must tell you that it is a city that I love and that has a very solid and consistent art scene. As a matter of fact, there are many Latin American artists living and working here, like Los Carpinteros, Teresa Margolles, Sandra Gamarra, Carlos Garaicoa, Alexander Apóstol. It is a very European city, but at the same time it has this Latin American flavor.

Patrick Hamilton, Redressed #5, 1997, contact paper on photograph, 7” x 5.” Courtesy the artist and Galería Casado Santapau, Madrid.

P.B. - Another element that caught my attention is that in 2010 you opened a gallery called González y González together with Daniella González and the participation of Jota Castro in Santiago de Chile. Did it function more like an artist-run space? A gallery for artists by artists?

P.H. - Yes, it was more a project space of artists for artists where the spirit of collaboration was very important, especially in a context like Santiago de Chile, where the art world is always quarreling and its members are not eager to cooperate. The project had a clear desire to exhibit and show the practices of artists who were linked to society in different ways and who intensified the relationship between art and politics. The project lasted four years (we closed it when we came to Spain in mid-2014), but it was important, as we made 24 projects in our space (a 40-square-meter department) and in institutions such as the Sao Paulo Cultural Center, the Santiago International Film Festival and the Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC) of Santiago. In addition, we participated in nine art fairs, including the Armory Show, Artissima and Art Brussels. The goal was, together with Daniella González and Jota Castro, to build a bridge between the art scene of Santiago, Latin America and the world. It was an ambitious project, done in a completely independent way and with very few economic resources, but which I think served in several ways to energize Santiago de Chile’s art scene. We showed for the first time in Chile the work of Santiago Sierra, Regina José Galindo, Darío Escobar, Carlos Garaicoa, Cinthia Marcelle, Wilfredo Prieto, Teresa Margolles, Alejandro Almanza Pereda and many others. We also showcased Chilean artists like Natalia Babarovic, Jorge Tacla and Sebastián Preece.

P.B. - The idea of setting up this kind of artist-run space and exhibiting the work of artists like Santiago Sierra, Carlos Garaicoa, Jorge Tacla and so on, as well as your own work, was it maybe motivated by a lack of artistic infrastructures in Santiago?

P.H. - No. I think there are many spaces in Santiago devoted to contemporary art, museums, galleries, art centers, cultural institutes, etc. Therefore, what we were looking for with our project was to showcase a different point of view. Our view on art, as I said above, has to do with a social and political perspective, which is obviously also the center of the concerns that both Jota Castro and I tackle in our own works. Also, the space had-I think that this is a characteristic of independent spaces-a lot of flexibility as we moved quickly without being hampered by bureaucracy. On the other hand, and no less important, there was the complicity factor; that is, the great majority of the artists we worked with were artists we already knew, with whom we had shared projects or coincided in exhibitions-many friends with whom we shared a common vision about art and the contemporary art system.

OVERSUBSIDIZED ARTISTS AND A LACK OF MUSEUM POLICIES

P.B. - But the Chilean art market is very small; there are hardly commercial art galleries. Some galleries, like Metales Pesados, had a short life. Others, like for example Isabel Aninat, do international art fairs in order to survive. I lived there myself when I was working at Matucana 100, so I had a brief first-hand experience. There are for sure interesting Chilean artists, but why do you think the Chilean art scene does not take off? A lack of private collectors? Insufficient state funding? Museums with no acquisition budgets? The expense of travel to and from Chile?

P.H. - All of the above. It is true that there is a strong contradiction between the economy of the country-Chile is by far the country that has developed more economically in the region in recent decades-and public funding in art, and especially private or corporate, although I must tell you that this has gradually changed. When I studied art in the mid-1990s, there was nothing there!

I think, on the one hand, that there is more compromise on the part of the private sector and, on the other, the state devotes too many resources to creation and production-through competitive grants and funds. But there is also budget and support of the institutions like museum and contemporary art centers, which should be able to generate quality programming, with a likewise budget, be proactive spaces and not merely receiving projects that are financed, most of the time of doubtful quality. That is the main problem, because the main museums in Chile can not define policies and put them into practice, they can’t hire professionals of a certain international standard that provide new or refreshing views, nor have museums that have the capacity to generate acquisitions policies. In short, we lag very behind in this sense. The surprising aspect is, in my opinion, that there is an excessive subsidy to artists, as individual subjects as millions of dollars are destined in production of work that then ends up in storages due to the lack of a system that absorbs, exhibits and distributes them.

In relation to the galleries, I think they do what they can. For our part, with González and González, being aware of this reality of lack of private and institutional collecting, we set out to maintain a space with very low operating costs in order to focus on the contents and the relationship with the international art circuit.

P.B. - Yes, Chileans are not very open to foreign ideas and foreign professionals. It’s also a fact that the Museo de Bellas Artes and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo are literally falling to pieces. But you’re certainly right about the excessive funding. It reminds me of the Netherlands in the 1980s: The state created artists that behaved like civil servants, and that was a total disaster. In this same sense, Chile has a very young but at the same time insignificant art fair, CHACO. Do you think Chile needs an art fair right now?

P.H. - I still think that Chile is a country more for a biennial than an art fair, as there is a lack of a consistent market that could sustain a fair of international-quality art. This does not happen. What is missing is education and the possibility of bringing contemporary quality art and confront it with the local scene so that we could generate a fabric. And I speak of a biennial in the sense of a major project that can support this educational function-education of the whole system, from schools, art students, to the collectors themselves.

P.B. - There is a lot of critique against art fairs these days. Jerry Saltz wrote an article titled “A Modest Proposal: Break the Art Fair” in Vulture in which he denounced the art fair-industrial complex and how it’s ‘killing’ galleries due to the high costs involved. What is your opinion about the role of art fairs?

P.H. - The fairs are a business for the owners of the fairs, as they are really the only ones that win. I believe that it is a very perverse system and that its days are numbered. The paradox is that there are thousands of galleries in the world that live and work in a city, but to subsist they must rent square meters in another country to try to do what they cannot in theirs. Likewise, in the art world you see exactly the same type of concentration of economic power that occurs in the world of financing; therefore, there are 10 or 15 galleries in the world that dominate the art market. This is a well-known story. Finally, there are quality fairs, the least, and a lot of trash fairs. I believe that good fairs, if they fulfill their role, which is to promote and sell art, are good and welcome. The rest are part of the perversion of the system that you mentioned.

P.B. - After this contextualization, it’s time to talk about your artistic practice. This implies necessarily addressing one of your first projects, the Redressed Architecture Project, which started in 1996 and has turned into a sort of ongoing project. It’s an intervention in both real and virtual buildings using collage and photomontage that uses the city of Santiago as point of departure. Can you explain its genesis and the conceptual strategies behind it?

P.H. - This research began in the context of the painting workshop at ARCIS University. If I remember correctly, it was necessary to propose an ‘expanded’ painting work related to the city, the street, in this case, with the immediate surroundings of the School of Art that was located in the center of Santiago. I proposed a work of architectural intervention, and from that moment I started to use decorative industrial materials such as wall hangings and murals as metaphors of this notion of ‘cultural cosmetization’ produced by advertising and the mass media-as you see, a very 1990s statement. This is how I started a series of interventions, both real and virtual (photomontage), in which I used these materials under the notion of displacement of painting towards architecture and urban space. The work of Christo and Daniel Buren and other artists who worked in the field of institutional critique were very present at that time. These intervention projects were carried out on heritage buildings and public monuments, where I sought to critically stress the notions of the public and the private, the masculine and the feminine, the ornamental and the monumental.

The first work I did in this line was at the Salvador Basilica in 1996, in which I intervened a part of the outdoor architecture with wallpaper, that particular part of the church where it was very common to see homeless sleeping and defecating. My idea was to create a strange and paradoxical environment, where the relations between house and not house, the hospitable and the inhospitable, were intentionally confused so that they problematized each other. Years later, and thanks to a Guggenheim fellowship, I started to work under the same logic of shifting materials for domestic/decorative use to the architecture of the buildings of ‘Sanhattan’ (parody name with which the new financial district of Santiago is known) to address clearly and eloquently certain conditions and transformations of the urban fabric of Santiago in the context of a neoliberal Chile. The notion of a monument, in relation to the first works, is displaced towards the idea of the ‘corporate building,’ understood as a monument to the triumph of capitalism in Chile and as an emblem of the new relations between architecture, power and spectacle.

THE CHICAGO BOYS, PINOCHET AND CHILE AS THE CRADLE OF NEOLIBERALISM

P.B. - This architectural project embodies one of the recurrent themes in your work: Augusto Pinochet’s implementation of neoliberalism in Chile in 1973 after he ousted Salvador Allende and became the country’s ruler, leading to a perverse alliance between corporations and the state.

P.H. - Yes, the reflection and questioning of the concepts of work, economic development, myth and history in the context of the last decades in Chile, particularly the period known as the post-dictatorship, have been the thread throughout my work. The Chilean case is very unique: We went from a democratically elected socialist government to a free market economy (what is known as neoliberalism) thanks to a military coup led and supported by the U.S. in the context of the Cold War. The process of the military coup, with all the deaths and violations of human rights, is defined by the Chilean sociologist Tomás Moulian as the first case in the world of a ‘neoliberal revolution’ implanted in Chile during the 1970s and 1980s by Pinochet and the group of economists known as the Chicago Boys.

Patrick Hamilton, installation view Queer Tools at Posada del Corregidor Gallery, Santiago de Chile, 1999, handsaws and enamel on wall Courtesy the artist and Posada del Corregidor Gallery, Santiago de Chile

On the one hand, I am interested in the fact that Chile is or can be considered the laboratory of neoliberalism, a country where for the first time the radical postulations of Milton Friedman were put into practice (reduction of the state and privatization of state enterprises, reductions of duties and taxes, promotion and deregulation of capital markets, etc.); and on the other, the repercussion and crises that several neoliberal measures have caused in Chile, Latin America and in the whole world today. There are numerous analyses, texts and books that have been written on the subject of inequality, concentration of wealth, corporatism, extractive capitalism, privatization of state enterprises, deregulation of markets, etc., all consequences of the neoliberal phase of capitalism developed since the 1980s and promoted on a global scale by the governments of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

P.B. - Yes, especially the book Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty shows how this is one of the most unequal periods in the history of mankind! We find a continuation of these neoliberal conditions of social violence and consumption in later wall works like Copper diamond (2010), Intersections (2013), Homeland and Freedom (2012), Chuzo (2012), Intersections (2014) and Black Cross (2014). But here the artistic approach is very sculptural and minimalistic. What triggered this solution that reunites concept and form in such an exquisite manner?

P.H. - One of the most important aspects in my work process has to do with walking through the city. I always go with my camera. It is something that many artists do, but for me it is fundamental since I nourish myself from what I see from different perspectives, be it objects, constructions, specific materials, etc. In this context, I began to photograph these particular forms, which are placed on the walls of houses and commerce in certain sectors of the city of Santiago de Chile and that are very special because they have a very decorative appearance, but on the other hand, they are very dangerous. Then I started developing these mural drawings, which, as you say, have a very formal character. This type of material can be seen, with different formats, in a large part of Latin America, but the ‘decorative’ protections of which I speak are unique; they are not used elsewhere. The wall protections are very sharp and refer to the fight against crime, as well as the protection of private property.

These works respond to a constant in my work production process in relation to the manipulation of objects and images loaded with content from a social, economic and cultural point of view. It also responds to the violence and inequality present in the Chilean society of the post-dictatorship and the impact of the processes of economic globalization perceptible in the urban fabric of the city of Santiago.

These works talk about limits and confinement, as well as segregation and social division, in a very simple way, drawing very basic and eloquent figures, such as the square or the rhombus, that are, from the geometric point of view, the simplest act of delimitation.

P.B. - In this sense, can we consider an earlier work such as the irreverent Queer Tools (1999) as a transition together with the series of working tools you made in this period to these just mentioned wall works?

P.H. - I think so. Another important aspect of my work is that I usually play with the architecture of the place where I exhibit. If it’s a white cube, I usually try to ‘mess it up’ a bit. I have developed many types of murals throughout these more than 20 years of work, from which you mention Queer Tools of the year 1999, through murals made with posters (that simulate marble or designs of flags) or wall drawings made with the beforementioned protections. In these works, I address various aspects that have to do with spatial and architectural intervention (create an environment, repetition as a continuum) while raising questions of historical and artistic order (the tradition of muralism, the wall as support), as well as questions of symbolic order (crossing between true and false, between decorative form and political content of objects or elements inside the image).

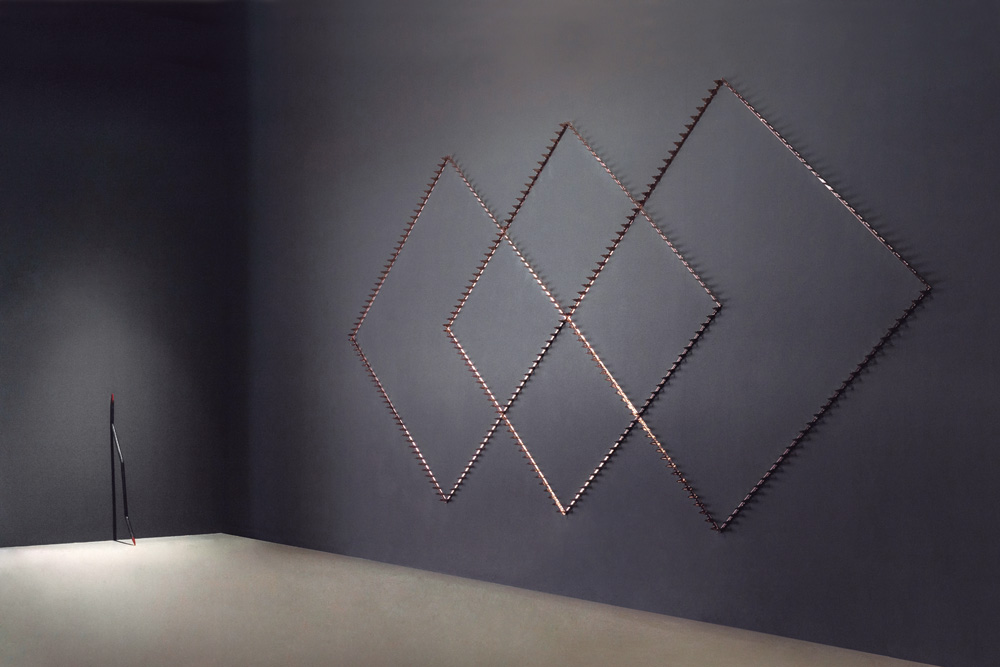

Patrick Hamilton, installation view at Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, 2014. Left Chuzo, 2012, iron and enamel, 63” x 15” x 1.” Right: Intersections, 2014, copper plated spikes wall protections, 110” x 220.” Courtesy the artist and Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw.

P.B. - Yes, you are right. You are one of the few artists that looks for solutions beyond the ‘white cube.’ This is very clearly visible in the installation Oversees South (2012) at the Paço das Artes in Sao Paulo, where a steel mockup plated in gold from a Nazi submarine is surround by wallpaper representing the Nazi flag. This belongs to a project related to the myth of the existence of Nazi gold in Chile. From a museological point of view, and to continue the connection with Queer Tools, how did you envision the dialogue with the space?

P.H. - In that exhibition, I presented the results of an investigation about some of the myths that circulate in Chile in relation to the hiding of Nazi gold in southern Chile and Argentina. In that form it was sent from Germany to the German colonies that since 1850 have been built within that area. In the room you describe, in particular, I try to make a kind of ‘cabinet’ transforming the Nazi flag into a sort of geometric wallpaper, eliminating the swastika, the iron cross and the red color. In tune with the imagery and the various signs that I found over the years that I worked on those projects, I wanted to make a montage, like a ‘montage of oddities,’ since it was the type of museography that best suited both the content and the formal result of the research, drawings, engravings and sculptures. In that sense, I wanted the assembly of the works to be coherent with the research and with the formal result of this to reinforce the ideas and concepts that surround those projects: the artist as a historian (in the Benjaminian sense), the tension between myth and history, document and fiction.

CONCEPTUAL CLARITY, FORMAL TENSION

P.B. - In sculptural installations such as Machetes construction (2010), Handsaws construction (2013) or the wall piece Handsaw (2013), you even pushed the limits a bit further by estranging or dislocating the ready-made objects. How did this operation come about?

P.H. - I would say that they are classic operations of ‘cutting and assemblage’ within contemporary sculpture, with which I tried to reinforce the idea of defunctionalization of the object, which in these cases has a meaning that goes beyond mere displacement in a Duchampian sense. Apart from being ‘unusable’ products due to the folds that have been carried out on its surface, in these installations the saws and machetes are in formal tension, being placed on the ground and forming a sort of ‘mandala.’ The copper saws refer to the world of work and mining, a complex universe that in Chile crosses the concepts of wealth and exploitation; and in the case of machetes, we’re confronted by objects/symbols of so many struggles of the past that they seem out of place or as if they just do not fit in the current context of neoliberalism. But from time to time, these objects enjoy a resurgence, the machete of course as a sign of movements of struggle and emancipation.

P.B. - I see in your work the same spirit as an artist like Santiago Sierra and his predilection for what we could frame as ‘political minimalism’: very formal, very polished and aesthetic but at the same time permeated with a strong political and social syntax. This creates a challenging contradiction between concept and form.

P.H. - The work of Sierra is very important to me. I see it as a reference in several ways, besides that we know each other and are very close. But I must say that my fascination with this relationship to abstract, geometric art with this kind of formal economy blended with a political conceptualism goes back to my time as a student in the 1990s.

I am referring here to the attraction I have felt for the avant-garde and post-avant-garde art movements oriented towards practices that we could call ‘social forms’ (as Christian Viveros-Fauné called them), or as Gerardo Mosquera would say, a ‘perverted minimalism’: an abstract and economic art in its forms but with a social dimension in its content. At the origin of my artistic practice there is the influence of movements such as Constructivism, Suprematism or Concretism, and Neo-Concretism in Brazil. I am interested in the idea of a ‘dirty abstraction and a povera abstraction.’

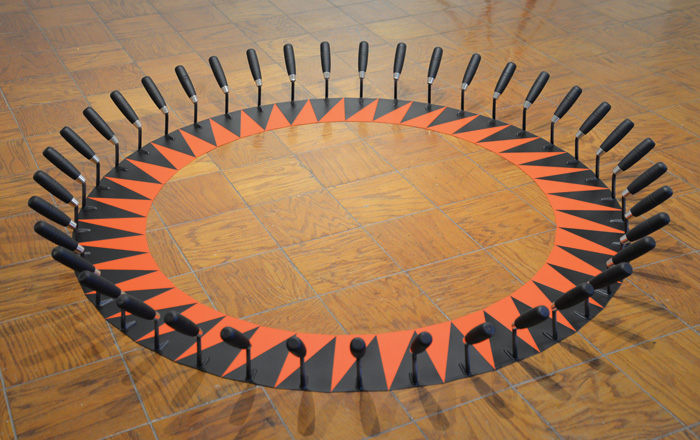

P.B. - Such as your installation Red and Black Sun (2017-18), a Merz-looking circle made out of trowel blades painted red and black at the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington, D.C.?

P.H. - Yes, that work makes a clear reference to constructivism, from the use of red and black colors to the sense and disposition of objects on the ground. This work, Red and Black Sun, is a kind of tribute to the world of labor and the collective sense that should guide the construction of a common vision and solidarity of the world and reality. The red-and-black flag that is painted on each of the planes responds in its origin to the colors of the anarcho-syndicalist flag, but also to the colors used by all the trade union and workers movements (ILO), from Italy and Spain to Latin America. The disposition on the ground, forming a circle, speaks on the one hand of a kind of state of repose of the tools, but at the same time of a tension, where the bodies are absent but at the same time present from the handles of the flat ones.

Patrick Hamilton, Handsaw, 2013, copper handsaw, 27” x 5” x 6.” Courtesy the artist and Galería Casado Santa Pau, Madrid.

P.B. - These series of sculptures with tools develop fluidly in your latest solo show at Galería Casado Santapau in Madrid in a set of paintings with tools titled The Brick (2018).

P.H. - Yes, for sure. In the exhibition that you mentioned, ‘the brick’ referenced several things: first as a book of political economy, then as a metaphor for the real estate crisis in Spain, and finally as a physical object that has three dimensions and builds walls. Then in that exhibition, there was a clear tension between object and painting, either by the tools-slats and spatulas-that were painted, the bricks, or by the use of the sandpaper as a ‘pictorial’ material. All the works referred to the world of construction, to that economic world represented by the worker, the bricklayer, in clear allusion to the crisis of labor that exists in the world. In this body of work titled El ladrillo (The Brick), a series of paintings/collages made with sandpaper, I ‘build’ the painting the way a bricklayer builds a wall or a pavement, through a repetitive and mechanical job that consists in forming frames and reticles. I think of simple forms, formal economic solutions-in the full sense of the word-but using elements that already carry a very important social and symbolic burden. So, my idea is to intervene as little as possible with these signs/objects that I appropriate to generate critical readings around the social context.

P.B. - Precisely, in The Brick, you twist the different connotations of the word, one of them hinting to Pinochet’s bedtime reading.

P.H. - The truth is that I do not think Pinochet read The Brick, or anything. The one that prompted the use of brick was José Toribio Merino, commander in chief of the Chilean Navy.

Patrick Hamilton, installation view Red and Black Sun at Art Museum of the Americas (AMA), Washington D.C., 2018, trowel blades and enamel, 70” diam. Courtesy the artist and Art Museum of the Americas, Washington D.C.

P.B. - I was being ironic…

P.H. - Right! The fact is that this book is very little known, but it has been fundamental for the history of neoliberalism in Chile and I would dare say that indirectly for the rest of the world. ‘The Brick‘ is a book of economic policy in which the guidelines of the free-market system that was implemented in Chile during the military dictatorship were established. The text was written, as I said before, in the early 1970s by a group of Chilean economists, students of the controversial Nobel Prize winner in economics Milton Friedman, at the University of Chicago. In its pages, the radical economic measures are proposed to be an antidote that should cure among other evils the Chilean society of socialism: the liberation of prices, the total opening of markets, the lowering of tariffs and taxes, the reduction of public spending and the promotion of privatizations of goods and services by the state. It is a book that summarizes the maxims of the Chicago School but is taken to the extreme. The Chicago boys’ Chileans took the teachings of Milton Friedman not only to practice but to the extreme. And I am afraid that the admiration that has existed among the rightists in the world for the economic ‘development’ in Chile, from Thatcher to Bolsonaro, is based on the ideology that the state should be as small as possible. As an anecdote, last week the representative of the Chilean extreme right, José Antonio Kast, was in Rio de Janeiro to express his public support for Bolsonaro. Well, he could donate a copy of ‘El ladrillo‘ (The Brick) to him as a gift so they can use it against PT socialism.

P.B. - When we started discussing your artistic practice in the mid-1990s you mentioned the idea of the pictorial. So basically, you are a painter working with ‘unpainterly’ materials.

P.H. - I studied painting since in the art school it was necessary to take the decision to follow a discipline like painting, sculpture, photography, etc. In a sense, my discourse and artistic practice are both born from the displacements of painting towards conceptual art. So yes: I am a kind of painter who paints with various objects and materials.

Patrick Hamilton, installation view El ladrillo, 2018 at Galería Casado Santapau, Madrid. Forward: Red and Black Column, 2018, acrylic on fire bricks, 70,8” x 15” x 15.” Back: Abrasive Painting # 53, 2018, sandpaper and acrylic on canvas, 63” x 45.” Fake wall, pink pladour, variable dimensions. Courtesy the artist and Galería Casado Santapau, Madrid.

P.B. - Finally, any unrealized or utopian project you would like to share with us?

P.H. - I have several projects for public space that I have not done since they are projects, let’s say more expensive, that need a bigger budget and a logistics that I have not yet achieved, although apparently I will soon be able to realize one here in Madrid. We’ll see…

P.B. - Sounds great to me! Thanks for your time.

Paco Barragán is a PhD candidate at the University of Salamanca (USAL) in Spain and the former visual arts curator of Centro Cultural Matucana 100 in Santiago, Chile. He recently curated “Juan Dávila: Painting and Ambiguity” (MUSAC, 2018), “Arturo Duclos: Utopia´s Ghost” (MAVI, 2017) and “Militant Nostalgia” (Toronto, 2016). He is the author of The Art to Come (Subastas Siglo XXI, 2002) and The Art Fair Age (CHARTA, 2008).