|

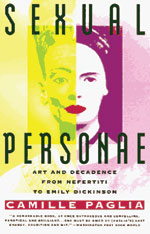

Camille Paglia. Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

Reports of the author’s death, says Paglia, have been greatly exaggerated. Artists in the Western world have always asserted their dramatic personalities and creative skill against nature’s tyranny. But nature, in its amoral chaos, is “no respecter of human identity.” Paglia bemoans the French Poststructuralist invasion of U.S. critical culture. Its high-abstract theory, and the overhyped, month-long Situationist liberation of desire, can only pale next to the U.S. counterculture’s 30-year, real-world Romantic pleasure quest. The American lunge at libidinal freedom via sex, drugs and rock and roll, launched by Little Richard and culminating in 1980s S&M dungeons, was a tragi-heroic lost cause. “The search for freedom through sex is doomed to failure.” Whether we rebel in theory or in practice, Paglia reminds us, “Nature is always pulling the rug out from under our pompous ideals.” And art leaves us artifacts of our spectacular defeat.

|