« Features

Jeff Koons at the MCA

The recent exhibition, Jeff Koons at the MCA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago) chronicled the prolific career of American art icon Jeff Koons. After presenting the first survey of Koons’ work in 1988, the MCA revisited the work of this seminal figure in contemporary art. The exhibition, the first major US museum survey of Koons in fifteen years, was only presented in Chicago. This was partly due to the city’s long history with the artist; a relationship unique to both Koons and the Museum.

“The contemporary artist and provocateur Jeff Koons is one of the most well known and intriguing artists of the 20th century. This is the line with which the press release opens, but whilst we cannot contest that Koons is interesting or that he is well known, it would seem from this exhibition that Koons the artist - who may at one time have provoked his audiences - is increasingly partisan; his career now divided into two categories: early work which provokes and later work which makes an unabashed bid for blanket acceptance.

It was said recently that upon viewing this exhibition, you realized that Koons has always been Koons. This maybe true in regard to his consistent efforts as a cultural producer to push the accepted boundaries of popular culture, and insofar as he has always been an artist who has looked for objects that represent our times, but as such he is governed by a constantly changing aesthetic. This being the case, despite a fairly formalized approach to art making, it is debatable whether he has been successful in retaining (or creating in the first instance) what could be referred to as “his voice.” In this recent exhibition in particular, where a great span of his career was laid bare, it was abundantly clear that even if Koons has always been Koons, he has made at least one major shift in his working methodology to date.

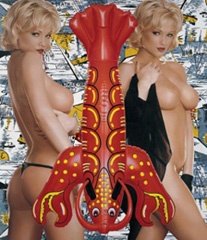

The easiest way to understand Koons is to take the example that he gave in regard to his series “Made In Heaven” (1989-91). More pornographic than romantic, the notorious campaign featured him and his new wife, Italian porn star turned politician, Cicciolina, indulging in unambiguous sexual acts. Koons insisted that the photographs in particular should be taken seriously as paintings, because they were printed with oil ink on canvas. He also claimed - tongue as always firmly in cheek - to have gone through a moral conflict which would take viewers into the “realm of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.” This sense of recreating icons comes through again in “Puppy” (1992), a forty-three-foot tall topiary sculpture of a West Highland White Terrier puppy. When anybody looks at “Puppy” (1992), they immediately relate to it because it is a puppy and it is made out of flowers - everybody can get it, everybody can love it. Everybody relates to the warmth and the pink and the yellows and the love. This trait of Koons of adopting popular icons, methods of production and specific styles is something that the artist has always done; however, one of the most obvious things to notice, when comparing his early work to that which he is making now, is that in the past Koons was noticeably more cynical.

Take, for example, “Michael Jackson and Bubbles” (1988), “Stacked” (1988), or “I could go for something Gordons” (1986) - these works are cynical. His ‘look’ on the hilarious poster advertisements for his older shows, for example, “Made in Heaven,” is uber-Eighties and purposefully aimed at attracting a corporate sensibility by mimicking magazine photography and make-up styles of the time. Here Koons is commenting about the art world and culture in an exclusive way, whereas as you go on in Koons’ career, he gets bubblier, happier, less critical and more inclusive.

His recent paintings too - weird pixilated abstracted canvases - are very typical of what painting is doing these days in that it is not so much about anything other than the language - it does not even matter how it is arranged, it is almost symbolic. Again he is emulating, producing, regurgitating.

Even “Elvis” (2003), from the series “Popeye” is inclusive; although it might initially seem to be provocative, it is in fact very conciliatory. Everybody loves porn, everybody loves baby toys, everybody loves playtime. Lately he has been producing these big juicy colorful paintings or big happy sculptures that are functional in their joy. It seems that the Koons of today is less concerned with critical cynicism, much in the same way that Damien Hirst or even to a lesser extent, Murakami, have drifted from controversy into safer more commercial waters. The question is: Did Koons lose his criticality or move away from it? The answer to this question really depends entirely on how you feel about Koons. His later work is not as engaging as the earlier pieces, but still it stands out from Hirst and Murakami simply because it is inclusive. When you look at Hirst there is always this element of cool or detached awe. It is as though he is pushing the buttons by putting dead things in tanks or making fun of art market values.

In the Eighties, Koons received some criticism for making work that was too cynical, too pessimistic. Today we see the fruits of his labor to get away from that stigma and move into more inclusive art work that is more sincere and warm. Many people think that it is successful, many do not, but whatever your feelings are toward Koons, he can always be relied upon to be just that little bit more honest, even without the cynicism, than his contemporaries. By comparison, artists like Murakami and Hirst, who are pandering to a market as opposed to nostalgic tendencies, do not hold equal water. It is of little interest these days whether an artist guts a cow and wears it or guts himself and puts it in a cow - such sensationalist methods, partly due to the original successes of their protagonists, are somewhat trite these days; viewed as increasingly weak and easy.

Koons, by contrast, stands out among his peers as being all about childhood. His paintings feature corn, green pastures and sprays of juice with cereal. There is also a feminine element that represents the sexiness of his work or the attractiveness, again, very inclusive - everybody gets that and everybody can get into that. A very good way of looking at Koons is through Norman Rockwell; the sculptures of bears and paintings of toys for example is very Rockwellian - full of sympathetic, emotional ideas. Here Koons is trying to appeal to a broad base, after all who does not love teddy bears and pigs and marble busts of love and fake flowers?

Koons stresses that making work, for him, is like playtime, even though his studio assistants rarely look like they are playing. As an artist he really just wants to play, to engage in play in the art world, within those barriers, making art toys for rich people.

The image of Koons, as portrayed in “The New Jeff Koons” (1980), perhaps sheds some light on these methods. Here Koons is pictured as a boy sitting happily beside a big box of crayons. Nothing really has changed even today; it is just Koons making playtime, only now there is more money involved, more production. This nostalgic quality to Koons is again an inclusive aspect to his oeuvre. Even his early work has a lot of religious iconography, the three basketball sculptures (one ball, two ball, three ball) from 1985 especially. They are all very precious, like reliquaries in a church vitrine - harking again to his abiding fascination for iconography.

One particularly interesting aspect of his later works, particularly the large balloons, is that they are now so far removed from their original inclusive idea, which we see in “Rabbitt” (1986), that they have practically come back full circle and are now almost depressing. Seeing these giant perfect stainless steel beauties so obvious and superficial in their joy, one cannot help but think of poignant monuments to failed love or living breathing meanings now encased and static - relics of a detached humanity preserved for posterity like Inca gold.

Chicago has served as the setting for a significant part of Jeff Koons’ artistic development and it seems only fitting then that now we should again find him there. Not only because that is where the majority of his works live, but also because it is a contextual stage, a field trip into the heart of the artist. Surrounded by a city vicariously familiar and breathing the same air as Koons, we see more clearly his progression, feel more connected to his decisions and appreciate him more reverently on this hallowed ground.

Ultimately it is very hard to be too critical about Koons, because there is such an air of false innocence about his work. It is obvious, yes, and often painfully so, but it is hard to dislike because it is not really saying anything and it is huge and it is well done. His penchant for the produced - his reproduction of the ready-made - is not ruffling any feathers, and, if anything, the fabrication of these benign icons has served not only to encapsulate 20th century history, but also to assert Koons as an icon himself within that time.

On view simultaneously at the MCA is a companion exhibition entitled “Everything Is Here: Jeff Koons and his Experience of Chicago.” This exhibition, courtesy of MCA curator Lynne Warren, aims to explore important works by artists that influenced Koons during his formative years as a young artist in Chicago. Often a little bit of a stretch and somewhat heavy on the work of Ed Paschke, the exhibition does offer some insight into the way Koons thinks, works and even possibly where he is going. As an artist who has appropriated almost every genre of popular culture he has lived through, the opportunity to postulate what could be next was a welcome treat. Regrettably, “Jeff Koons” at the MCA closed on September 21st. Nevertheless, “Everything is Here: Jeff Koons and his Experience of Chicago,” which draws primarily from the MCA collection, will be on view until October 26th, 2008.

Thomas Hollingworth graduated from London Guildhall University, UK, with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 2003. He has since worked internationally as a freelance writer for artists and dealers of note, and in Miami for institutions such as The Margulies Collection at the Warehouse and Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin.