« Features

Joan Jonas / Venice

By Anne Swartz

American Joan Jonas’ art is a subtle and complex interplay of images arranged like words in sentences and paragraphs engaging with the simultaneous denotative and connotative meanings of language. She has used video and sound, installation and performance to showcase the essence of social, lived experience, first exploring gender, then visuality, and more recently, the environment and our relationship to it. She emerged as a second-generation feminist artist in the 1960s and 1970s, merging her chosen imagery into personal, but not autobiographical, meditations on contemporary life.

This year, she represents the United States in the 56th Venice Biennale with her exhibition “They Come to Us without a Word,” curated and organized by Paul Ha, director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) List Visual Arts Center, and Ute Meta Bauer, founding director of the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, Nanyang Technological University, and previously an associate professor in the Department of Architecture at MIT. It is on view from May 9 through Nov. 22. The exhibition was accompanied earlier by “Joan Jonas: Selected Films and Videos, 1972-2005,” a complementary show presented by the MIT List Visual Arts Center that ran from April 7 to July 5. Jonas is Professor Emerita in the MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology in Boston.

The Italian exhibition is organized around the spatial necessities of the pavilion building itself. The U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale is a classical-style structure made in the Palladian symmetrical form. Built in 1930, it is the work of American architects William Adams Delano and Chester Holmes Aldrich. At the entrance of Jonas’ multifaceted piece, the viewer first encounters a bundled group of nine tree trunks from nearby Certosa Island. The colonnaded and pediment-topped façade at the pavilion entrance brings the visitor into a circular rotunda where Jonas has inserted a series of manipulated mirrors-intended to recall the variations in aged mirrors-alternating with windows and arches allowing passage to the two galleries located in each of the wings on either side of the central passage. Above, this circular space is lit by crystals arranged in large swooping circles and curves, almost like chandeliers. In each of these four galleries, there are two video projections accompanied by more mirrors, along with drawings, kites and props.

Installation view of Joan Jonas’ They Come to Us without a Word (Nine Trees), 2015. The US Pavilion at the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia; commissioned by the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Moira Ricci.

The overarching notion guiding the viewer through this complex series of images and forms is that of the philosophical, cum environmental, fantasy of our Anthropocene age by Icelandic Nobel Prize Laureate Halldór Laxness’s 1968 novel Under the Glacier, translated into English in 2005. This selection by Jonas resembles her past explorations into literature as a subtext, such as her reverie about Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, a 14th-century text centering on a protagonist’s journey (in that earlier text, specifically a passage through hell, purgatory and finally, heaven). In Laxness’s work, the journey takes the hero and his helpers into a volcano on an Icelandic glacier, into a subterranean realm. One subtext of this book is the encounter with nature that dominates and commands our attention, its small subtleties, like a bee pollinating a flower, becoming necessary but occurring without human intervention like miracles.

Installation view of Joan Jonas’ They Come to Us without a Word (Mirrors), 2015. The US Pavilion at the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia; commissioned by the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Moira Ricci.

In Jonas’ project, the entry installation of the trees is significant because of the source, which references the fleeting reality of nature and human interaction with it. Ceratosa Island is close to the main Venetian island and was being developed into a multi-use park, housing development and recreation area when a massive tornado delayed the expansion and, notably, destroyed much of the island’s forests. The trees are also evocative, to me, of Dante’s use of the tree in the ring of the suicides in the seventh circle of his Inferno. In Dante’s Weltanschuung, the suicides are besieged by the terrifying harpies, mythic female birds who violently rip and gnash at their branches and trunks, forcing the damned soul to re-experience death eternally. Since many species of deciduous and coniferous trees continue to grow a season after they are cut down, the tree is a symbol of sadness and loss vis-à-vis the suicide metaphor, but also an emblem of resurrection and rebirth-the reality of nature sustaining itself (and ultimately humanity). The copper wire binding these logs together puts them in a complementary and linked state with each other, thus making them dependent as well as interconnected and reliant.

The idea of hope continues into the pavilion. In another example of Jonas utilizing prominent literary source material, the mirrors are her inheritance from Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges’ short stories. In these stories, the mirror is a persistent leitmotif. Borges’ mirrors are numerous and varied, named or referencing the monstrous to the alternative. They are a material Jonas has utilized since the 1960s in performance and video. Alongside the lighting she has had produced for this space, the mirrors have an intentionally distorting visage. They recall the sensuous and surreal encounter Orpheus had with his image prior to tripping into the netherworld in French filmmaker Jean Cocteau’s 1950 film. The peculiar insertion of these manipulated mirrors, which Jonas had specifically fabricated in nearby Murano, which is internationally known for its glass production, adds to the fantasy of her presentation. The strange and inaccessible appearance of these mirrors also invokes the idea of change since the mirrors are no longer clean, clear and entirely functional, another attribute recalled by the tree trunks at the entrance. The narrative of aging as loss is not what Jonas is after here, because she installs these mirrors in a well-lit, bright location. They do not suggest the dark, dank interior of one of Charles Dickens’ spaces. However, they do suggest another realm, which Jonas has summoned as a theme in this project: that is, the invocation of ghosts into the space of the exhibition.

Installation view of Joan Jonas’ They Come to Us without a Word (Homeroom), 2015. The US Pavilion at the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia; commissioned by the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Moira Ricci.

In each of the four galleries, Jonas includes two videos and a range of objects.1 The recordings are a combination of older and newer pieces used as backdrops for filmed actions by a group of children whose ages range from five to 16. They were made in Nova Scotia and Brooklyn. The over-arching atmosphere of natural change, play and beauty are central and steadfast images in these projections, which include underwater scenes, close-ups of bees, and views of the ocean and forest. The benign and exuberant children interact or move as if in theatrical performances of the everyday-braiding one another’s hair, walking, reading. The artist also appears, often masked, in her videos, as she does in these ones. Several narrators, also including the artist, read text, which have the effect of giving the impression of a fantastical world of fairy tales, a source for Jonas. The sound is synchronized with the movement of the performers and animals in certain instances and arbitrary in others.

Installation view of Joan Jonas’ They Come to Us without a Word (Fish), 2013-2015. The US Pavilion at the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia; commissioned by the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Photo: Moira Ricci.

Each of these gallery spaces is complex. Between the two projections, one acts as a ghost-like presence for the more dominant version in the same room. Within each, as has been Jonas’ tendency in the past, the point of view changes regularly. Sometimes, the action is pushed to the forward picture plane of the screen or the screen is split, skewing the orientation in one or more directions. Sometimes the speed is standard and other times slowed or expedited. One recurring component in the installation is the use of a pleasing, bright lighting. A not-unusual feature of artistic fascination with Venice has been the light with all the reflections cast by the water. From the rotunda, with its strong natural light to the four galleries with video, the light is ambient but ever-present. Sometimes projections must be showcased in dark interiors, heavy curtains blocking all light. Even in the places where darkness does shroud some of the pavilion space, enough to make it possible for the viewer to see the images, the lighting in Jonas’ videos is strong, daytime lighting (which is another component by which I see Jonas contemplating the human encounter with nature in her subtext to the whole project).

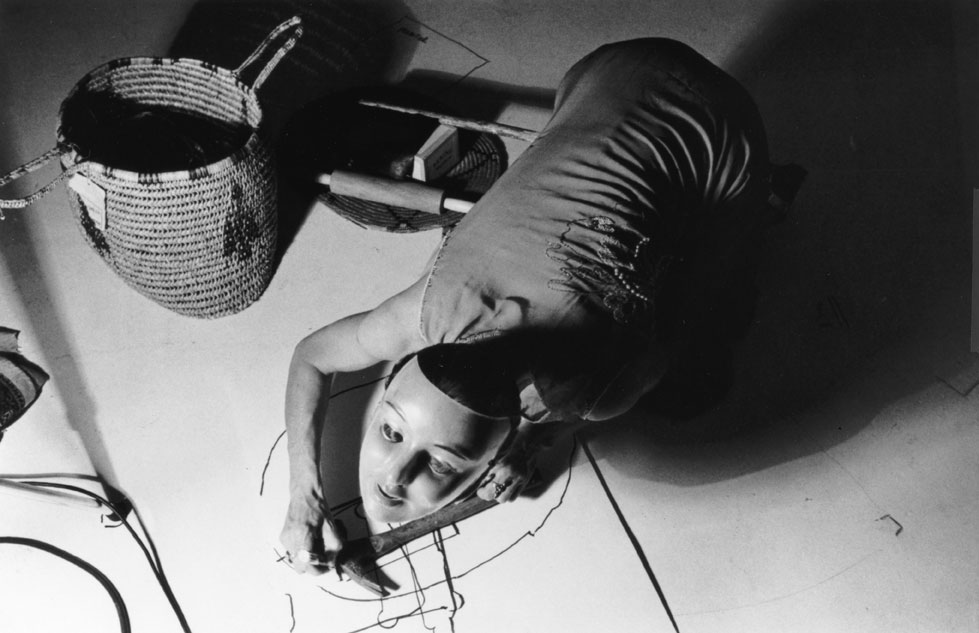

Joan Jonas, They Come to Us without a Word II, 2015, performance with music by Jason Moran, Teatro Piccolo Arsenale, Venice. Pavilion of the United States 56th International Art Exhibition - la Biennale di Venezia. Presented by the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Moira Ricci.

Drawing has been a major component of Jonas’s oeuvre, so it is not surprising that she includes them in the Venetian installation. They mostly appear in large, gridded installations of single objects presented in monochromatic contour drawings on a white background. In one example, images of bees in honeycomb-shaped nodes are perpendicularly abutted by a large grouping of drawings of bees.

While this role as the American artist selected to represent the United States at this major international art festival could be seen as a culmination of Jonas’ career, it is, in fact, one more step in her artistic production. But it definitely brings together many experiments that have been perennial for her. The artist grew up in New York City, then studied art history and sculpture at Mount Holyoke College. Next, she went to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston before returning to NYC and completing her graduate work at Columbia University. She has lived, worked and exhibited internationally but calls New York her home.

Joan Jonas, They Come to Us without a Word II, 2015, performance with music by Jason Moran, Teatro Piccolo Arsenale, Venice. Pavilion of the United States 56th International Art Exhibition - la Biennale di Venezia. Presented by the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Moira Ricci.

Active since the 1960s, Jonas started as a sculptor and shifted into more performative modes. As she experienced the avant-garde investigations of New York artists in the early 1960s, she found herself propelled into new directions. As the artist said in a recent interview, “What attracted me was that you could be a visual artist and do something time-based.”2 These include a single occasion visiting Claes Oldenburg’s two-month installation The Store of 1961 at the Museum of Modern Art. The milieu of the day and much exciting activity were there, which included alternative concerts at composer and musician La Monte Young’s studio. Subsequently, she encountered many of the artists associated with Judson Dance Theater from 1962 to 1964, including Robert Rauschenberg and choreographers Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, Simone Forti, Steve Paxton, Trisha Brown, and Yvonne Rainer. They were also participants in the original collaborations of numerous artists and engineers for the grand art and technology performances known as Nine Evenings in 1966, largely orchestrated by Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver. They were all tackling different perceptions of art and visuality, breaking away from the doctrinaire ideas about media and art. As well, there was experimental theater, also downtown, that was another influence on Jonas.

The artist took a cue from their innovations, splicing completely different and distinct forms into single works. She began performing, working with video and then choreography, the leap that would take her on a trajectory into an interdisciplinary approach to her practice. Jonas’ work has numerous traces and resonances from her encounters with these artists in her art even now.

Joan Jonas, They Come to Us without a Word II, 2015, performance with music by Jason Moran, Teatro Piccolo Arsenale, Venice. Pavilion of the United States 56th International Art Exhibition - la Biennale di Venezia. Presented by the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Moira Ricci.

Jonas would heartily engage with technology, above and beyond the performance that remains a stalwart component of her practice. Recently in an interview she remarked about its predominance and import: “I’ll say one thing about technology-you can’t separate my work from technology, because my work exists within the fabric of technology. And it’s also affected by it. So technology is inseparable from my work.”3 Video was emancipating for her, as well, since it was an area relatively unexplored or dominated by male artists.4 She was able to utilize it in original ways. In 1968, working with other artists who would make themselves available for one another’s projects, Jonas created Wind, a video lasting under six minutes made using a Sony Portapak. Made in Long Island, the wind was ferocious, and the temperatures haltingly silhouette the figures moving in precise and arbitrary ways to showcase their bodies and render them into anonymous figures. The compression of narrative, the straightforward emphasis on the visual and the simplicity of the movements recall works like Rainier’s Trio A of 1966, a radical and simplified presentation in which the performers exist in a domain separate from the spectator, never making eye contact, but remain accessibly grounded in the present.

Jonas used video and performance to craft intimate visual ruminations, allowing her to showcase the female form and experience. She filmed an alter-ego she called Organic Honey in videos in the early 1970s, examining ideas about social expectations of women.5 She began considering that video and performance combined gave her opportunities to craft multivalent compositions. Even as her work took up the revolutionary mantra of the Women’s Liberation Movement that “the personal is political,” they are not autobiographical. One such example would be Good Night Good Morning of 1976, in which the artist captured herself greeting a welcome or gesturing a farewell (or both) as a daily ritual. It is intimate and showcases her engaged in the most basic kind of everyday exchange, like a circadian action. She also segued in the 1980s and beyond into relying on textual references more and more. Double Lunar Dogs of 1984 is a video project that Jonas based on the short story “Universe” by American science fiction author Robert Heinlein. This kind of appropriation would continuously expand and evolve in Jonas’ work. From 2002 to 2005 in Lines in the Sand, a performance commissioned for Documenta IX in 2002, the artist probed two poems by the American poet Hilda “H.D.” Doolitle to produce a present recasting of the mythical Helen of Troy using the Hotel Luxor in Las Vegas as a way to contemporize the situation.

One of the fascinating trajectories Jonas has also explored recently is stage design. For the 2014-15 installation of Safety Curtain, an ongoing project to display contemporary art on a large-scale before, during and after an opera performance, Jonas developed beautifully colored patterned and abstract surface treatments. Whitney Museum of American Art curator Chrissie Isles noted the recurrence of the theatrical space in Jonas’ art, creating “a dialogue between depth and distance within framed space, with the usual elements of live performative action displaced onto the performers of the opera, hidden behind the screen.”6 It is a three-dimensional, lived translation of seeing and experiencing, as she has merged them often in her art.

Jonas joins an august group of artists in representing the U.S. at the Venice Bienniale. She is only the eleventh woman exhibited there.7 While she has garnered widespread and extensive attention in Europe, she is only now getting similar recognition at home for her multisensory, polysemic projects. “They Come to Us without a Word” is a fascinating and intense work in the continuum of Jonas’ career. It also coalesces many of her approaches, forms and themes, making it a useful way to explore the range of her achievements.

NOTES

1. A short video glimpse into Jonas’s installation can be viewed at https://youtu.be/3cp8wYljFco.

2. Joan Jonas, Interview by R.H. Quaytman, “Interview with Joan Jonas,” Interview (December 2014) http://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/joan-jonas# (accessed on June 5, 2015).

3. Ibid.

4. “Joan Jonas on Feminism,” MoMA Multimedia (2010), http://www.moma.org/explore/multimedia/videos/110/508 (accessed June 1, 2015).

5. Esther Adler, “Joan Jonas,” in WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, edited by Cornelia Butler and Lisa Gabrielle Mack. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2007, p. 251.

6. Chrissie Isles, “Joan Jonas - Safety Curtain 2014/15,” Wiener Staatspoer (2014), https://www.wiener-staatsoper.at/Content.Node/pressezentrum/Pressemappe_Jonas-en.pdf (accessed June 1, 2015).

7. The women who have represented the U.S. in the past include: Louise Nevelson (1962), Helen Frankenthaler (1966), Diane Arbus (1972), Agnes Martin (1976), Melissa Miller (1984), Jenny Holzer (1990), Louise Bourgeois (1993), Ann Hamilton (1999), Jennifer Allora (from Allora & Calzadilla 2011) and Sara Sze (2013). Only Holzer, Bourgeois, Hamilton, Sze and Jonas were solo installations.

Anne Swartz is a professor of art history at the Savannah College of Art and Design. She has focused her lectures, writings and curatorial projects on feminist artists, critical theory and new media/new genre. She’s currently co-editing The Question of the Girl with Jillian St. Jacques and completing Female Sexualities in Contemporary Art and The History of New Media/ New Genre: From John Cage to Now.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.