« Reviews

Law of the Jungle

Lehmann Maupin Gallery - New York

By Denise Carvalho

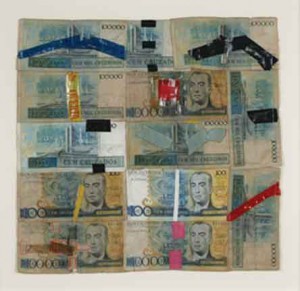

In “Law of the Jungle,” shown at Lehmann Maupin, from December 9, 2010, to January 29, 2011, contradictory explored post-humanism meets form, examined here from a Brazilian art historical perspective. Making references to Anthropophagy (1928-1934) and Neo-Concretism (1959-62), the show suggests expanded shifts that contextualize and hybridize art through tensions between aesthetic form and the social space. This can be seen through a cannibalizing of various art histories, while attempting to break away from their linear canonical development. At the same time, the exhibition attempts to resituate art today as anti-historical on one hand, and on the other decentered, displaced, intertextual, and semi-autonomous. What is absurd in the show is how a nihilist view of art history draws exactly on movements that argued for local specificity as critical resistance against foreign cultural importation. In this cannibalization of various art trends, one can see everything from psychedelic and allegorical to neo-pop and post-conceptual. With artists from Brazil, Great Britain, United States, Israel, and Bali (although 15 of the 23 artists were Brazilian, including the curator himself), “Law of the Jungle” seems to imply that survival is not just that of ‘no rules apply’ of developing nations, or their artists who lack visibility, but also those who have it. Survival seems here a strategy of convenience. Privilege can be detracted through the focus of relational discourse, which is perhaps the most interesting aspect of this show. But then what’s the point of the work in terms of artistic intention, development, or trajectory? Os Gemeos, Free Freedom, for example, whose street art started out as specifically anonymous and interventionist, now seems to focus on the art object. Does Free Freedom means a negation of freedom through the art object as an individual’s investment vis-à-vis art as a commonwealth? This ironically parallels Jac Leirner’s Blue Phase, a collage with Brazilian currency devalued by hyperinflation. What about artists who have been very visible, especially because of their conceptual ideas, such as Liam Gillick, but whose work here becomes merely indexical of other works in space? This also allows us to think of curating as an art form that destabilizes the possibilities of specific styles, wondering whether its intention is to strategically and politically bypass the significance of singular art toward that of relational and collective.

Jac Leirner, Fase Azul (Blue Phase), 1995, Brazilian currency, electrical tape, fabric, thread, 14.37” x 14.02.” Courtesy of the artist, Yvon Lambert and Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York.

As the exhibition addresses issues of economic productivity, excess, and waste-also expanded to an excessive and wasteful use of colors, materials, and narratives-its carnivalesque curatorial gathering appears to be more celebratory than critical, while the simplicity of certain works, such as Marcos Chaves’ Untitled, stills the show in its inquisitive intimacy. Chaves’ work consists of a bamboo fishing rod with the Buddha’s image on the viewfinder, which hangs as bait at the end of the string. The placement of the work in one of the corners of the back room is of great importance since it comments on the bended line as a reference from Copernicus to Land Art and beyond. Marepe’s Untitled poster makes an allusion to the Bumba Meu Boi folkloric festival in Brazil’s North and Northeast, an allegorical performance that narrates the death and resurrection of the ox. Marepe’s work takes the human/animal relation to the next level, equating animal and human exploitation as contingent to the conflation between decolonization and re-colonization. Adriana Ricardo’s paintings, with aerial views of Rio de Janeiro’s slums, Rocinha, Santa Marta, and Turano, known as highly exploited commodities for tourism, NGOs, and the arts in the last ten years, return to a fetishistic and voyeuristic optics on the theme of the marginalized. The question in the show is whether these artists’ works add anything other than reiterating their allegoric neo-cannibalistic trends as new blind spots in the exportation and marketing of culture.

(December 9, 2010 - January 29, 2011)

Denise Carvalho is an art critic, curator, and professor at Institute of Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in Portland, Maine.

Filed Under: Reviews