« Features

Lucian Freud The Self-portraits. A Trans-Atlantic View

By Tim Hadfield

“Lucian Freud: Self-portraits,”is an Anglo-American curatorial project between the Royal Academy of Art, in London, and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. The exhibition features drawings, paintings and etchings from the artist’s late teens and every subsequent decade of his life. The Royal Academy exhibition ran for four months into early 2020, while the tenure of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts exhibition that began in March, was unfortunately cut short by the early intervention of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lucian Freud, Reflection (Self-portrait), 1985, oil on canvas, 55.9 x 55.3 cm. Private collection, on loan to the Irish Museum of Modern Art. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images.

The idea of this unique exhibition was originally mooted by David Dawson, Freud’s dedicated assistant for the last twenty-one years of his life. It is a signal and refreshing reminder of both his rise in stature to acknowledgement as the greatest figurative painter of his generation, and a fascinating distillation of this evolution. Yet this accolade came slowly and there was a time in mid-career whenFreud’s canvasses, steeped in tradition and featuring as subjects a sprinkling of the rich and famous, but primarily partners, friends and family, seemed out of step and out of their time-a quirky anachronism in fact. The Self-portraits illuminates how Freud became cool and crucial again, with his mastery of technique, his ability to reinvent the most traditional subject matter of all, and how he was able to reposition figurative realism, by the early years of the 21stcentury.

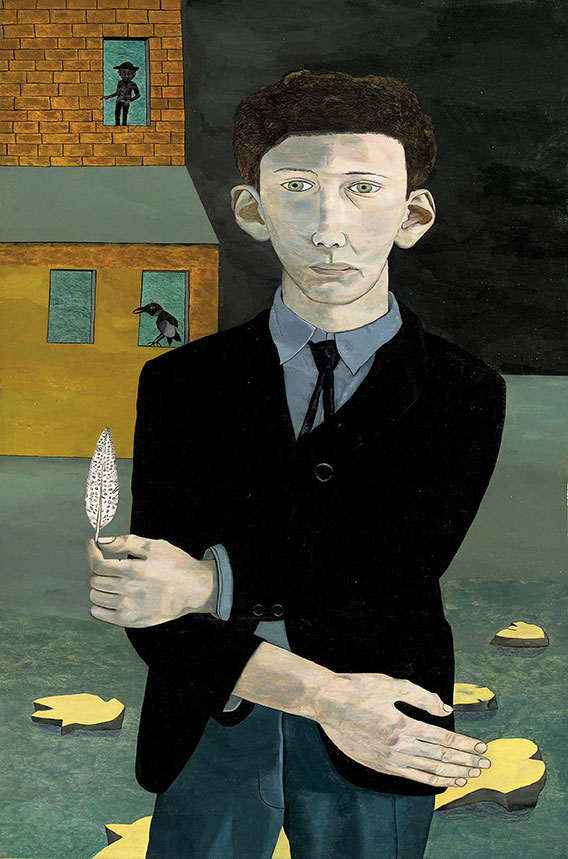

Hung chronologically, the exhibit starts with Freud’s art-school drawings and paintings which demonstrate originality and ambition, but not yet greattechnique. This limitation can be observed in Man with a Feather (Self-portrait) (1943). Though painted when the artist was only twenty-one, its self-conscious, faux naïvetégrabs our attention, but does not suggest the master draftsman he would become. In this respect, Freud’s earliest work reminds one of Van Gogh’s, who also wrestled with accurate representation in his early drawings, giving no hint of the fiery masterpieces to come, including his own melancholy, but beloved and uplifting series of self-portraits.

Interestingly, there are further parallels between these two great painters of the self-portrait. Both artists were the loners from financially comfortable family backgrounds, their highly motivated personalities driven by an energy and urgency to convey the emotion and interior lives of their subjects. They also had all the connections any ambitious artist could want, though they strived to succeed without them, and in each case their technical growth is exponential.

In his early work, Freud intends to distance himself from his peers and avoid the academic canon of a British tradition of portraiture centuries in the making. In Freud’s youth, its roots were in the painting of William Coldstream, and the Euston Road School. This group stressed careful observation and measurement, along with a certain required accuracy in life drawing, prevalent in art schools of the era. Contrarily, Freud was also obviously aware of the post-war generation of British artists whose raison d’ être was to take the figure as far away from that exacting tradition as possible. The bulky bronzes of Henry Moore and the flayed figures of his future friend, Francis Bacon, demonstrate two ends of this revolt against tradition. Freud, however,remained in the seam between these groups, where he also mined the magnificent work that flowed from the Renaissance to the Old Masters, found in the great museums of London he frequented.

Lucian Freud, Man with a Feather, 1943, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 50.8 cm. Private collection. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images.

In the paintings of the 1940s and 1950s Freud achieves this separation from his peers bywillfully distorting the features of his sitters, particularly faces, while clinging to an otherwise conventional technique. Eyes, particularly,assume Sumerian proportions, noses and ears grow alarmingly and enlarged hands flag emotions. Correspondingly, the extraneous areas of forehead, hair or even body often shrink. Such exaggerations of form could have looked unconvincing, even cartoon-like, were it not for his blossoming painterly skills, that invest one’s gaze in the veracity of such liberties.

The precision of this early work of Freud’s from his late twenties and the following decade demonstratethe importance of line. Faces and bodies are often finely delineated and enclosed by a crisp outline which is to a certain extent ‘filled in’ with a flat and even gradation of value. In Man with a Thistle (Self-portrait) (1946), the thistle leaf vies with the artist for dominance, its spikey form a vaguely threatening presence. Does the thistle imply his vulnerability, his own unapproachability–or even suggest of a ‘crown of thorns’? His face is often set against such sparring partners of assertive natural forms yet unknown metaphorical intent. In Still-life with Green Lemon (1947), a dominant pairing of a leaf and lemon painted in fine detail is accompaniedby a sliver of the artist’s face, peering around a corner as if a voyeur spying on the viewer. Leaves, a lemon, a feather—the symbolism is not clear. Although we struggle to decode them, we sense their significance to him, and his affinity for the simple beauty of natural forms—despite his unwillingness to give up the human form completely.

In the ink drawing Self-portrait as Actaeon (1949), the title finally gives us context, with the Greek myth of the goddess Diana, surprised while bathing nude, by Actaeon, a hunter. Offended, she transforms him into a deer, whereupon he is killed by his own hunting dogs. The artist looks surprised, deer antlers sprouting from his head. On his face, may be the splashes of water from Diana’s rejection, or possibly tears rolling down his cheek, as he portrays his conflicted duality as powerful stag and vulnerable young man.

Surely Freud is already referring to the recurring subject of his sexuality and relationships with women, the scale of which is a modern myth in itself. His legendary charisma and rotating relationships make Mick Jagger appear a shy Puritan by comparison,and has resulted in Freud fathering at least fourteen children, including three girls born in the same year to three different women. To have multiple partners is not so shocking, but to impregnate so many women from whom he later separates, seems much more than accidental and is…unusual. The content of his work and his personal sexual encounters become increasingly intertwined throughout the rest of his life, to the extent that they largely become the content of much of his work, with his female models also often his lovers.

In Hotel Bedroom (1954), Freud’s technique is now exquisite with finely detailed and silky brushwork. The painting painfully records an episode in his relationship with his second wife Caroline Blackwood. Painted in Paris, the year after their marriage, the artist puts himself in shadow as Blackwood’s fraught face tells its own story of a passion play that already appears to be ending badly. He looks, not down at her fraught face in sympathy, but at us the viewer, as if to admit hisculpability. It is difficult to imagine Blackwood’s state of mind sitting for this double portrait, but it speaks to Freud’s inability to put his private life above his art to expect her to do so, and the painting serves as a public confessional of sorts.

Lucian Freud, Hotel Bedroom, 1954, oil on canvas, 91.5 x 61 cm. Gift of the Beaverbrook Foundation, collection of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images.

Soon after his split from Blackwood in the mid 1950s, the influence of Francis Bacon, now a close friend, and the painter Frank Auerbach, helped bring about significant change in his technique and working methodology. Bacon’s canvasses, with those surfaces of screaming high key color, have a surface that is sometimes scraped and blurred,aptly describing their tortured subjects. Auerbach, a less familiar artist in the US, builds his portraits and cityscapes from an extraordinarily thick impasto surface of interconnected and overlapping angular bars, squiggles, skids, and smudges of viscous paint–almost as if straight from the tube. Freud was inspired by both artists, who became the closest of friends. He collected their work, and for the rest of his life would usually call Auerbach to his studio for comment beforecompleting his paintings.

Their example gave Freud license to explore a more radical paint application and he gradually abandoned his small sable brushes and the fluid application of smooth glazes, for thicker paint. Paint was now not just a vehicle for content, it was content itself. He also decided to paint standing up, a stance that keeps one’s concentration focused and invariably above the eye level of the subject. This choice also gave rise to more full-length portraits, something he continued until his death. A less obvious transformation was more radical though. Freud had said of this period that he had “stopped drawing”. What he really meant by this, wasthat he didn’t preconceive the composition as he used to, by drawing out the preliminary composition inside what he felt was a proscribed line. Instead, this previously omnipresent habit was abandoned, in favor of a far more gestural sketching out of the sitter’s pose and mass.

David Dawson’s beautiful book A Painter’s Progress, published in 2014 three years after Freud’s death, illuminates very clearly the new preparative process for his paintings. Bold expressive lines are drawn spontaneously from the subject onto the canvas and repeatedly overdrawn, usually in graphite. The arc of the artist’s wrist and arm movement is evident, as he attempts to build the form to catch an essence of the pose or face. The effect is not unlike the heavily cross-hatched technique displayed in the etchings, but it is clearly a more exploratory formative expression of the composition and contrasting values of light. Having abandoned the fine detail of the earlier work, he now favors the firmer bristle brushes which have the strength and spring to pushand pull the viscouspaint across the surface of the canvas. This in turn introduces a physicality to the surface which more convincingly fits his active working posture and inclination to constantly alter his paintings. The thicker ‘fat-over-lean’ oil painting technique is designed to allow for the slower drying time of thicker ‘fat’ paint on top of the ‘lean’ thin, or glazed areas. This prevents later cracking of the top layers of paint. Thicker wet areas can be scraped off more easily too and the resulting scrapings can be seen flicked onto his studio wall in many studio photographs. From this juncture onwards, the visibility of brushwork and the thickening layers of paint increasingly dominate the surfaces of his paintings. As Freud himself puts it, “I want the paint to work as flesh does.”

When posing his models Freud increasingly chooses a viewpoint well below his eye level looking down onto them, he is then able to see more of the recumbent figure without as much foreshortening. This flatness viewed from above onto the subject, is reminiscent of Degas, whose masterful draftsmanship he greatly admired. Degas is also renowned for alterations to his work, particularly the drawings. The ballet dancers, for example, often possess multiple legs–from which the viewer instinctively picks out the truer ‘correct’ pose. In Reflection with Two Children (Self-portrait) (1965), Freud employs a mirror placed below knee-level, perhaps even flat on the floor, for a distorted worm’s eye view of his reflection. This time, the foreshortening of the figure is extreme, with his large body tapering away from us to a smaller head–a reminder perhaps of the distortions that so intrigued him in the faces of his early paintings. The tilted plane of the mirror plays tricks, stretching his face into an asymmetrical bias as if by its gravitational pull. Concentric circles of the light bulb and shade over his shoulder must surely be a playful nod to the influence of Bacon who used such a device repeatedly–as did Picasso before him. The two cheerful children added at the bottom of the composition are oddly disconnected from the composition, their perspective in opposition to that of Freud’s, whose face looks down at us with an analytical gaze. Caught as if painted in minutes, the children are portrayed at a far smaller scale than the artist himself and could be mistaken for a photograph in the frame of the mirror. They appear a late addition for his own amusement. After all, artists do not expect to sell their self-portraits just as Degas didn’t his drawings. Theyare to learn from and experiment with, though by now Freud and his friends Bacon and Auerbach knew, without false modesty, that somebody would buy anything they painted.

Lucian Freud, Reflection with Two Children (Self-portrait), 1965, oil on canvas, 91 x 91 cm. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images.

This technical liberation, meant that in the formative early stages of compositions, the previous continuity of line became a continuity of color and value, with fine detail sacrificed for repeated applications of wet-in-wet paint. Edges could be soft as well as crisp, lines literally blurred between contours, and the dimensionality of the more modeled surface made the figure appear almost in motion, rather than frozen in place as before. Now, the physicality of the paint and his struggle to manipulate it, was closer to expressing the character of the sitter rather than illustrating it. This is not to denigrate those exquisite early paintings of his first wives, for example,which remain enormously popular, iconic even, images. But his change also freed Freud to work more quickly and make those spontaneous alterations and adaptations he savored too. In the past a decision to change the pose of the model part-way into the painting, would have been almost impossible, given the finely detailed surface. Now it became something we know he did quite often, moving his model’s poses or limbs usually, but as we have already seen, sometimes adding or removing a figure, by scraping off or overpainting the unwanted content.

Throughout his life, Freud turned away from his sitters on occasions, to paint himself, plants, and fragments of landscape. This was his practice when the stress of his complex personal life provoked an exodus to a more literal and less animated subject matter: a viewof his garden, a corner of the studio, or perhaps the view out of a studio window. Painting animals, too, gave him pause from the human figure-from trips to the stable to paint horses, not to mention his beloved dogs, Pluto and Eli, that were frequently bit-part players.

This practice is referenced inInterior with Plant, Reflection Listening (Self-portrait) (1967-68), in which a potted, variegated plant dominates the composition. Its technically challenging tangle of radial overlapping leaves almost hides the artist, positioned as a reflection from behind and between them. He has his hand lightheartedly cupped behind his ear as if listening to the plant. The technique has still not quite fully adopted the bucking and rollicking brushstrokes which overtook his increasingly fluent surfaces in a few short years. Freud spoke of the difficulty of painting landscape and plants, as if it werea penance to paint them—and with the revolving door of his lovers, perhaps it was. His casual comment that “When I took one tiny leaf and changed it, it affected whole areas” contains within it, not only the challenge of these subjects compared to the ‘easier’ figurative work, but also reveals a key tenet of Freud’s practice—his adherence to the absolutism of observation. In that quote, the artist tells us that even in a landscape comprising plants with hundreds of leaves, he still tries to position each leaf exactly. It’s a fact that most ‘realist’ painters would resort to texture, or a general impression of the leaves. As early as the mid 19th century, Corot was a master at this soft-focus rendition of foliage, which was a technical sensation before the Impressionists claimed the idea outright. Freud’s admiration of Constable’s late ‘six-footers’ was another such precursor to Impressionism that influenced him with their spontaneous brushwork and bold scumbling, again an innovation completely without precedent when executed in the early 19thcentury.

The same point concerning Freud’s attachment to truth in representation, can be made by his constant repetition in the titles of these self-portraits of the word‘reflection.’ The artist affirms that he does not want us to forget that what we are seeing is not the truth, but instead a flipped rendition of him and his world. Just as we forget so quickly that what we see of ourselves in the mirror every day is false, a literal ‘mirror-image’ of what everyone else sees. Of course, if he missed flesh, he could paint himself, and juggle that act of honesty without artifice. Freud described this challenge to his last dealer William Aquavella; “You know for me it’s very difficult to do a self-portrait because I don’t want to make myself look too good, but I don’t want to make myself look too bad, and to get it just right is very difficult.”

At the age of sixty-three, Reflection (Self-portrait) (1985), shows a shirtless Freud with the movie star good looks of a tough guy Robert Mitchum or Liam Neeson. A highlight catches his forehead at a receding hairline and down onto the prominent ridge of his nose; he appearsa younger man, still well-muscled for his age and at the height of his powers as a painter. The craggy, faceted modeling of the face appears almost carved out, and now it is easier for us to understand how women were so attracted to him, even at this age. In the shallow space between nose and ears, he creates depth effortlessly, placing the most delicate transitions of color and value, adjacent to one another, realized as distinct brushstrokes. His features sit perfectly in place and in plane, with a nose that intrudes confidently towards our gaze. The dimensionality of the modeling is achieved with audacious swirls and facets of buttery oils, their textured striations left by the hog’s hair brushes. This physical surface catches the light differently to lend an immediacy that is so astonishingly fresh, it makes the artist appear almost confrontational. An understated backdrop of the same hue of flat umber is laid down at different angles, subtly animating the light this way and that.

The slow burn of Freud’s rise to prominence is illustrated by the gap between his inaugural solo exhibition at the Hanover Gallery in 1944 at age twenty-two, and belated recognition in America when his first museum show in the United States opened over forty years later in 1987 at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D.C. Writing in the accompanying catalog, Robert Hughes referredto Freud as “the greatest realist painter alive,” and his subsequent representation by William Aquavella’s Gallery in New York, sealed the transatlantic connection. Nevertheless, this recognition from perhaps the pre-eminent critic of the day, had been a long time coming. The year after though,Hughes’ assertion was cemented world-wide, when Freud’s, Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995) sold for $33.6 million, a then record price at auction for a painting by a living artist.

The point here is not that Freud was neglected financially earlier in his career, he wasn’t. Despite his relatively slow output with his demanding technique, there was a constant flow of work to his dealers–Freud had followed Bacon’s exampleof working primarilywith private dealers rather than blue chip galleries. With the artist usually in the studio seven days a week, combining day and night sessions, his work ethic constantly reflected his once stated intention to, “paint myself to death.”He was in fact a wealthy man from his early thirties, with a lifestyle which enabled him to rub shoulders with, and marry into—Caroline Blackwood was heiress to the Guinness estate—the higher echelons of London society. Nevertheless, although inclusion in the 1954 Venice Biennale had indicated his prominence nationally at that time, it is twenty years before his first retrospective in Britain at the Hayward Gallery in 1974. Those intervening years were filled by his own account, with “dancing and nightclubbing and dice games and (London’s) Soho”. It was also the time he was consumed with the fascinating transitions of his painterly technique.

Meanwhile, Freud’s American contemporaries of this era, chief among them the New York School, were hanging out at Cedar Tavern in the East Village, and the subsequent Warhol crew, at Studio 54. On the West Coast,Ed Keinholtz’ Barney’s Beanery awaited immortality and the Ferus Gallery stable in LA were still playing catch-up. This mid-century blossoming of new genres helps explain why recognition eluded him for many years. The cultural and societal revolution of the 1960s that birthed the rise of entire art movements from Pop-Art, Op-Art, Minimalism, Conceptual Art, Environmental Art, to Performance Art, Installation and so on, were generated primarily in America. Even though the ripples reverberated across the pond, the ‘School of London’ group, a loose collective of artists who worked with figuration including Freud, Bacon and Auerbach continued unabashed, as these changes seemingly passed them by.Their disjunction from the prevailing art world climate speaks not of an oblivious ignorance of the cultural upheaval around them though, but of an unequivocal confidence that the younger Auerbach, and Freud invested in their own painting, an affirmation in fact, of their more contiguous practice. And in the 1980s, critical opinion circles back, to rejoin them.

One truly great painting is still to come at the end of the exhibition: Painter Working, Reflection (1993), is a stunning full-length portrait of Freud in the studio, naked (what took him so long?) except for his trusty painting boots, at the age of seventy-one. He stands as he works, palette and palette knife brandished as if the sword and shield of a gladiator daring the young pretenders to take him on–and they still can’t. If it is a merciless depiction of old age, it is simultaneously a victory of truth over ego. This self-portrait also displays the increasing tendency in his later paintings to obsessively rework specific areas of the painting until the paint forms a thick accretion of textured paint not found in other areas of the canvas. This habit grew with the later work and some observers find it an uncomfortable distraction. Perhaps his eyesight is declining slightly at this point, or does he just increasingly enjoy demonstrating the struggle of a painting’s metamorphosis? The brushwork certainly doesn’t always have the fluency of the mid-to-late career paintings, but as this painting proves, from even a short distance away, optical color mixing lends a smooth transition of color, and form, which is what Freud most sought. The exhibition catalog also illustrates an earlier version of the painting ‘in progress’ and the most obviously reworked area is Freud’s face, in which he had later ironically given himself a much less complimentary appearance. When Freud did hit what he thought of as painterly problems, he explained that he visited his favorite masterpieces in the great London museums, declaring almost apologetically, ”I go and see pictures rather like going to the doctor, to get some help, in fact.” This comment was caught on video as he was talking in front of that same Titian, Diana and Actaeon (1556-59) in the National Gallery in London, which must have inspired him so many years earlier.

And which American figurative painters could we compare Freud to at this peak? Hopper has the same intimacy and brooding sexuality, but held literally, at a distance. De Kooning is also an earlier generation and perhaps more akin to Francis Bacon, Diebenkorn too abstract, and Katz too formulaic. Pearlstein has the same love of the nude, but in comparison to Freud, his workslook dispassionate and absorbed with technique. Alice Neel gets close, in part. Closer, though tied so specifically to a sense of place, is the work of Andrew Wyeth, whose painting has the same rigor and investment in the lives of his sitters. Wyeth’s practice appears nevertheless, so wrapped up in the rural landscape of Eastern Pennsylvania and the surrounding farming community,or his summer home in Maine, thatthe figure is often not even center stage, as it invariably is for Freud. In Britain, the artist who has a surprisingly close affinity to him is in fact from the previous generation of painters, the mystical and mysterious Stanley Spencer. Not well known in America, his few early nudes such as his double portrait with Patricia Preece are stunning and sexually loaded. The manner in which Spencer would make forays into landscape as Freud does, also makes them appear quite empathetic partners, despite Spencer’s departure on an inexorable journey towards religious mysticism in his extraordinary large mural paintings. David Hockney and Freud were friends and both managed to co-exist without treading on each other’s figurative toes. Hockney loves to draw and work in an array of media, Freud is wedded to oil paint. Freud’s practice revolves around the few square feet of his studio, Hockney loves to travel, living in L.A. for more than fifty years and more recently England and France. There was no rivalry and Freud painted a fine, gently humorous small portrait of Hockney, who has now assumed Freud’s mantle of Britain’s ‘greatest living painter’ and is regarded as something of a national treasure.

Among the new contemporaries, the figurative genre has been stretched by among others, Eric Fischl, Kara Walker or even Cindy Sherman, although they necessarily relinquished the observational realism still found in the work of Elizabeth Peyton, or Kehinde Wiley, President Obama’s portraitist. Lasting contributions to self-portraiture in other photo-related media include those by Warhol, Bruce Nauman, Mapplethorpe, and John Coplans. In Freud’s native Britain, women are dominating figurative painting and receiving just recognition. Celia Paul, a former partner and muse of Freud, who was subjected to the worst of his manipulative behavior, has emerged with her sensitive portraits. Powerful portrayals of women by Paula Rego continue to challenge patriarchal stereotypes and the more recent emergence of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s lush and seemingly spontaneous paintings of black and brown subjects, possess an uncanny presence. Jenny Saville’s work and that of Cecily Brown have made a powerful impact both sides of the Atlantic for some time. Saville, with her obsession for flesh and perhaps even fellow Brit, sculptor Marc Quinn in a perverse way, echo the influence of late Freud with their interest in gender identity and atypical bodies, while retaining a Freud-like attachment to academic realism.

Unfortunately, what we don’t see in this particular exhibition isthe fascinating evolution in Freud’s choice of sitter in the later studio works, which influenced so many of this younger generation: Big Sue,the ‘Benefits Supervisor’ and Leigh Bowery already a famous London performance artist before he sat for Freud, renowned for his exotic costumes and androgynous personas. Both were very atypical body types in the 1990s. Twenty-five years later Freud’s paintings have helped make them cultural icons, now thatbody image and gender fluidity is mainstream and we have again caught up with him. Freud painted both of them multiple times in large canvasses which are now recognized as some of his very finest works. Bowery sadly died of AIDS aged only thirty-three. These paintings alone brought many younger admirers back to his work and they continue to grow in popularity connecting with the public wherever they are exhibited.

Caroline Blackwell, Freud’s second wife who is so dramatically featured in Hotel Bedroom (1954), spoke of Freud’s “ability to make people and objects that come under his scrutiny seem more themselves, and more like themselves, than they have been—or will be.” It was as if he reached into them and turned them inside out, their existential core mapped out by every angle of a pose, each nuance of color, or translucency of skin—all made ‘shameless’—a word he liked to use—before us. In this exhibition, we now witness him striving to do the same with his own body.

Lucian Freud, Self-portrait, Reflection, 2002, oil on canvas, 66 x 50.8 cm. Private collection. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images.

These self-portraits by Freud will undoubtedly last for generations to come and are the closest companions to the unmistakable series of masterpiece collections of this genre thatcan be mentioned in the same breath as those of Durer, Picasso, Kahlo, the revered masterpieces of Van Gogh and ultimately, the impossibly magical self-portraits of Rembrandt. In these paintings Freud was likewise able to make biting insights into a personal life that wascomplex, layered with intimacies, and shared with so many. It is a life too rich and unknowable to judge from a distance. Wecan, though,assess the work he has left us itself, which has its own life. We do after all, feel we know Rembrandt and Van Gogh from their self-portraits and we empathize with the highs and lows of their dramatic lives that we know both artists experienced. It is a fact though, that without photography, we have no idea if the self-portraits even look anything like the artists who painted them. They are a kind of truth beyond proof. A series of images we whole heartedly connect with, and believe in. Freud’s self-portraits carry with them as a group thesame unmistakable honesty which brings with it that same transcendence.

* “Lucian Freud: Self-portraits” was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts, London from October 27, 2019 to January 26, 2020. Then, the exposition travelled to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and was on view from March 1stto March 11, 2020.

Bibliography

- Compton, Susan. ,British Art in the 20thCentury: The Modern Movement. Royal Academy of Arts, Prestel, 1987.

- Cusk, Rachel. “Can a Woman Who Is an Artist Ever Be Just an Artist?” New York Times 11/07/20

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/07/magazine/women-art-celia-paul-cecily-brown.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

- Dawson,David.A Painter’s Progress: A Portrait of Lucian Freud. Jonathan Cape, 2014.

- David Dawson, Joseph Koerner, Jasper Sharp and Sebastian Smee.Lucian Freud: The Self-portraits. London:Royal Academy of Arts, 2019.

- Feaver, William.Lucian Freud Drawings. Blaine I Southern and Aquavella Galleries, 2012.

- Hoozee, Robert (ed.). British Vision: Observation and Imagination in British Art 1750-1950. Museum Voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent & Mercatorfonds, 2008. Distributed in North America by Cornell University Press.

- Lampert, Catherine (ed.).Lucian Freud: Recent Work, exh. cat. Whitechapel Art Gallery, London; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, 1993.

Videography

- Jake Auerbach,Lucian Freud: Omnibus, 1988. Omnibus BBC 4 Collections, (41:37 mins)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6u-uySBESgU

- David Bickerstaff (dir.)Lucian Freud: A Self Portrait. Exhibition on Screen, documentary (1hr 20 mins). Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jWwpVmgvFog

- Randall Wright (dir.)Lucian Freud Painted Life: The Last Genius of 20th century Realist painting. BBC (1hr 29 mins)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VA6yGLydWtc

Tim Hadfield is a British artist, curator and writer who is a professor of media arts at Robert Morris University in Pittsburgh, where he was the founding head of the department. He has exhibited widely in the United States and Europe. Hadfield has lectured at many renowned institutions, including Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Savannah College of Art & Design, and the University of the Arts and Royal College of Art, both in London. He has curated exhibitions across the U.S. and international projects in Australia, England, Hong Kong, China and Chile. In 2003, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, Great Britain, and in 2010 co-founded the nonprofit Sewickley Arts Initiative.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.