« Features

Measuring Disturbances

How Media Look at the World

By Christiane Paul

Ideally, today’s media landscape could function as a way of measuring the political, economic, and social disturbances in our societies’ structures, thereby helping us to find a basis for action and adjust structural problems. Then again, media themselves can be seen as a disturbance of reality, being able to technologically record, refocus, edit and replay the world surrounding us and, in the process, both perturbing and reflecting upon it.

Looking back at the global crises of the past few years, one might ask whether one is observing yet another failure of the media’s corrective function: did we not understand the behaviors and variables of our environment well enough to get a sense of disturbances, and take action before slipping into a worldwide economic crisis and breakdown of systems? Does the contemporary media landscape create too much of a disturbance to be able to measure disturbances in the world outside itself? Are we twittering ourselves into oblivion?

Christopher Baker, Hello World! or: How I Learned to Stop Listening and Love the Noise, 2008, multi-channel video projection, sound. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Chris Houltberg

Numerous media artworks created throughout the last decade have engaged with the beginning of the 21st century and its potential, addressing historical events, economic interdependencies, and possibilities for agency and democracy. The fact that these projects actively deal with contemporary societies, rather than exploring formal concerns, raises questions about the artworks’ intent and the role that art can play in commenting on or bringing about social change. The latter usually is the domain of activist art, where the artwork itself commonly incorporates the audience’s active participation in addressing a cause. Some media artworks are not explicitly activists, but reflect on current conditions and raise awareness about them, which can be seen as at least an essential aspect of an activist agenda. One of the essential characteristics of art is its capacity to open up spaces for exploration, experimentation, and critical reflection on the world surrounding us and on the function and aesthetics of art itself. Media artworks that deal with political and social conditions cannot avoid commenting on their own status, that is, the medium they use and its relationship to power structures. Control over media and their distribution constitutes political power as theorists including Herbert Marcuse and Jean Baudrillard pointed out decades ago.

Digital technologies, from computers to the Internet, are inextricably tied to the military-industrial-entertainment complex, and many new media works critically engage with this circumstance. This is not to say that the problematic aspects of the history of technological progress make new media art inherently tainted or flawed. One could argue that media art offers an ideal space for exploring the condition of media and its complex structures. As many media theorists have argued, any form of critical engagement with, or intervention in, the media has itself to employ media.

The effects of simulated realities, relationships between media and consumerism, and the rise of social and participatory media are some of the aspects that characterize the language of today’s new media. On the one hand, digital technologies have brought about shifts in the realm of collage, montage, and compositing, by creating the ability to seamlessly blend visual elements with a focus on a new form of reality, rather than the juxtaposition of components with a distinct spatial or temporal history. On the other hand, digital media allow for the creation of simulated virtual worlds that either recreate existing physical environments or produce alternative realities. Simulation can be defined as the imitative representation (the artistic likeness or image) of the functioning of one system or process by means of the functioning of another. A flight simulator, for example, replaces the functional reality of navigating a plane with the digital simulation of this process. Simulations are now a familiar part of the media landscape. We encounter them in videogames, commercials, or recreations of conflict and disaster, be it war or traffic accidents. During the Iraq war, TV news reports frequently made use of simulations to illustrate military strategies or recreate missions. Simulations are usually geared towards being as close to physical reality as possible. Their representational quality has become a major goal in science, as well as the gaming and entertainment industries, which continually strive to imitate the look of actual, physical objects or live beings.

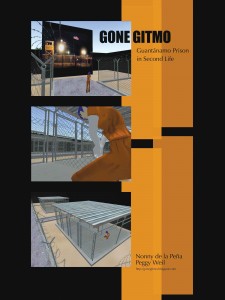

Langlands + Bell’s The House of Osama bin Laden (2003), Nonny de la Peña and Peggy Weil’s Gone Gitmo (2007-present), and T+T (Tamiko Thiel and Teresa Reuter’s) Virtuelle Mauer / ReConstructing the Wall (2008) are all simulations of actual architectures that comment on simulated representation from different angles. Part of The House of Osama bin Laden project is an interactive 3D simulation of the house in which the al Qaeda leader lived in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. The bare, empty structure of Bin Laden’s house simultaneously becomes a loaded monument to the al Qaeda leader’s legacy and a testament to the impossibility of fully understanding a person through the space he inhabits. Rather than claiming to be a rendition of the real (as many simulations in the media do), the project renders any claim to reality problematic. Does the simulation and pursuit of the most accurate representation of physical reality bring us any closer to an experience and understanding of the site, or significance of its former inhabitant, his life and death?

In de la Peña and Weil’s Gone Gitmo, questions surrounding reality and experience are addressed from another perspective. The project was created in the virtual world of Linden Lab’s Second Life, which bills itself as the world’s largest, user-created 3D virtual world community1. As a simulation, Gone Gitmo provides access to the high-security site of Guantánamo prison, which remains inaccessible to an average person. The project does not attempt to create a simplistic impression of the real Guantánamo; it breaks up the simulated environment by incorporating different media formats, for example, documentary material such as video and transcripts from FBI interrogations. The “scripted experiences” of the artwork effectively use the power of simulation: people visiting the project in Second Life temporarily lose control of their avatars who are subjected to imprisonment. The artists do not pretend to simulate the actual experience of being imprisoned in Guantánamo, yet visitors’ loss of control over their virtual bodies can have a powerful effect. It strips them of the essential quality of the virtual experience, the possibility of interactivity and agency in the virtual world.

Nonny de la Peña and Peggy Weil, Gone Gitmo, 2007-present, virtual environment in Second Life. Courtesy of the artists.

As Gone Gitmo, Virtuelle Mauer/ReConstructing the Wall (2008) by T+T (Thiel and Reuter) reenacts a structure that has been an icon of political conflict, in this case a section of the Berlin Wall. T+T’s project, however, uses simulation to anchor the experience of the wall’s complexity of history throughout decades and rebuilds an architecture that is now gone. Fusing archival material with the possibilities of interaction, the users’ actions in the environment shape the virtual scenes they encounter.

As Gone Gitmo, Stephanie Rothenberg’s and Jeff Crouse’s Invisible Threads (2008) also uses Second Life as a framework, but comments on the intersection between virtual and actual world economies rather than qualities of representation per se. The mixed reality installation allows people to order, through a retail kiosk in the exhibition space, a pair of jeans, which is then virtually manufactured in a Second Life factory by worker avatars-representations of actual people around the world who have been hired through Second Life classified advertisements. The virtual jeans are output back into the physical world as actual jeans via a large-scale printer. Invisible Threads explores the ways in which virtual economies have begun to intersect with those of the real world. Items from online games are now frequently traded for real currency. Sweatshops in China engage in the business of “goldfarming,” where players of online games pay “farmers” (players who repeat mundane actions in a game in order to collect points) to gather in-game rewards for them in order to play the game at a higher level. According to Wikipedia, 2008 figures from the Chinese State valued the Chinese trade in virtual currency at over several billion yuan, or nearly 300 million USD. Anshe Chung, the avatar that entrepreneur Ailin Graef created for herself, made headlines in 2006 for building an online business in Second Life-devoted to development, brokerage, and arbitrage of virtual land, items, and currencies-that made her a real world millionaire. It was the avatar Anshe Chung (rather than Graef, the person) who was featured on the cover of Businessweek2, signifying the definitive arrival of the simulacra (in the Baudrillardian sense) as commodity.

All of the four simulations mentioned here explore qualities of representation that we encounter in simulated environments: the status of the real; the recreation and mediation of past and present; and the simulation as commodity. As such, they measure the disturbances created by the media in their manufacturing of realities.

While 3D simulation may not be the most common form of representation we encounter in today’s media landscape, the concept of simulation in a broader sense-as a manufactured reality-has become pervasive. From movies to advertising and the news, the depiction of “reality” (as we would physically experience it) is increasingly augmented, manipulated and beautified by means of digital technologies, which presumably has a profound effect on our understanding of concepts of authenticity and history. Reality as presented by the media may have always been ideologically informed, but digital technologies have taken the possibilities of a simulated reality to a more sophisticated level. Both, the manipulation of reality, and the ideological impulse behind it are becoming harder to distinguish or trace.

The intersection of commerce and simulated reality in the contemporary media landscape is perfectly captured in the Russian artist group AES+F’s video Last Riot, exhibited in the Russian Pavilion of the 52nd Venice Biennale (2007). Fusing the photographic with digital animation, the video juxtaposes scenarios of collapse with a cast of young models-evoking Abercrombie & Fitch or Calvin Klein ads-who float on patches of ice in an arctic landscape. Dreamily swinging golf clubs and running swords across each other’s throats, the pale, angelic creatures bring to mind a media world where decapitation of terror victims and branding of lifestyle exist side by side. Last Riot evokes a dystopic image of a synthetic, slick and narcissistic world where the only imaginable agenda for a riot seems everyone’s own best interest.

Stephanie Rothenberg and Jeff Crouse, Invisible Threads, 2008, mixed media installation, Internet (Second Life), video. Courtesy of the artists.

While Last Riot may evoke a dystopian view of the world and the media representing it, the current media landscape has also brought about unprecedented levels of participation and agency. Today’s media are significantly affected by the concepts of Web 2.0 and “social media”-content created by means of highly accessible and scalable publishing technologies that rely as much on Internet-based tools as on mobile devices to access and distribute this content. Blogs, Wikis, and social networking sites such as Facebook, YouTube, and the micro-blogging site Twitter have seemingly raised the importance of user-generated content. Christopher Baker’s artwork Hello World! or: How I Learned to Stop Listening and Love the Noise (2008) explicitly engages with the possibilities and realities of Web 2.0. Consisting of a wall of thousands of video diaries collected from the Internet, the project raises the question whether the opportunity to make your voice heard and have agency in the world, turns into a noise of thousands of dissonant voices that makes it hard to filter for meaning. Web 2.0 sites are a hyperlinked corporate broadcasting environment that both allows people to build networks and share information and, at the same time, hands over substantial rights over the user-generated content to corporations.

Social media broaden the idea of the cultural commons and its platforms-assisting cultural communities in staying informed and improving policies that shape cultural life-and provide a pool of information that can be data-mined for commercial purposes. One could argue that the mostly profit-oriented structures of economies, industries, and institutions, in which digital technologies are embedded, contradict the idealistic belief in grass-roots change and activism that is driven bottom-up rather than top-down. However, the two prove to be co-dependent. Corporations develop tools that are carefully calibrated to cater to the personal and cultural desire for creative production in order to generate profit. At the same time there is no doubt that digital communication networks have enabled unprecedented forms of collective agency. Network technologies made citizen journalism a serious player in the media landscape, and social media are playing a significant role in election campaigns and the ongoing “Arab Spring.”

While the focus of the artworks discussed here may vary considerably, many of them implicitly or explicitly engage with the state of today’s media-be it with the nature of mediated realities; the intersections between art, media, and commerce; or social networking. In different ways these projects measure disturbances in today’s world, ranging from political events and new social or economic conditions, to those that are created in the media’s reflection of the world. They illustrate the complexities of new media landscape, in which ideology, the image, and commerce are increasingly co-dependent, and networks have become social capital. Art may not be able to control the variables of our world, but it remains an ideal platform for a much needed reality check that provides insights on the nature of the world and the way it is mediated.

NOTES

1. <http://secondlife.com/>

2. <http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/06_18/b3982002.htm>