« Features

Melvin Martínez: Material Sensations and the Artificial Flesh of Color

By Barry Schwabsky

“Each writer creates his precursor,” wrote Jorge Luis Borges. “His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future”(365). Likewise with painters. And one reason why Melvin Martínez counts as a painter is that he is showing us, in a new way, why Jackson Pollock still matters. Or perhaps it would be better to say the same thing in a different way: He is reminding us that the legacy of Jackson Pollock is still up for grabs-can still be, in Borges’s word, modified.

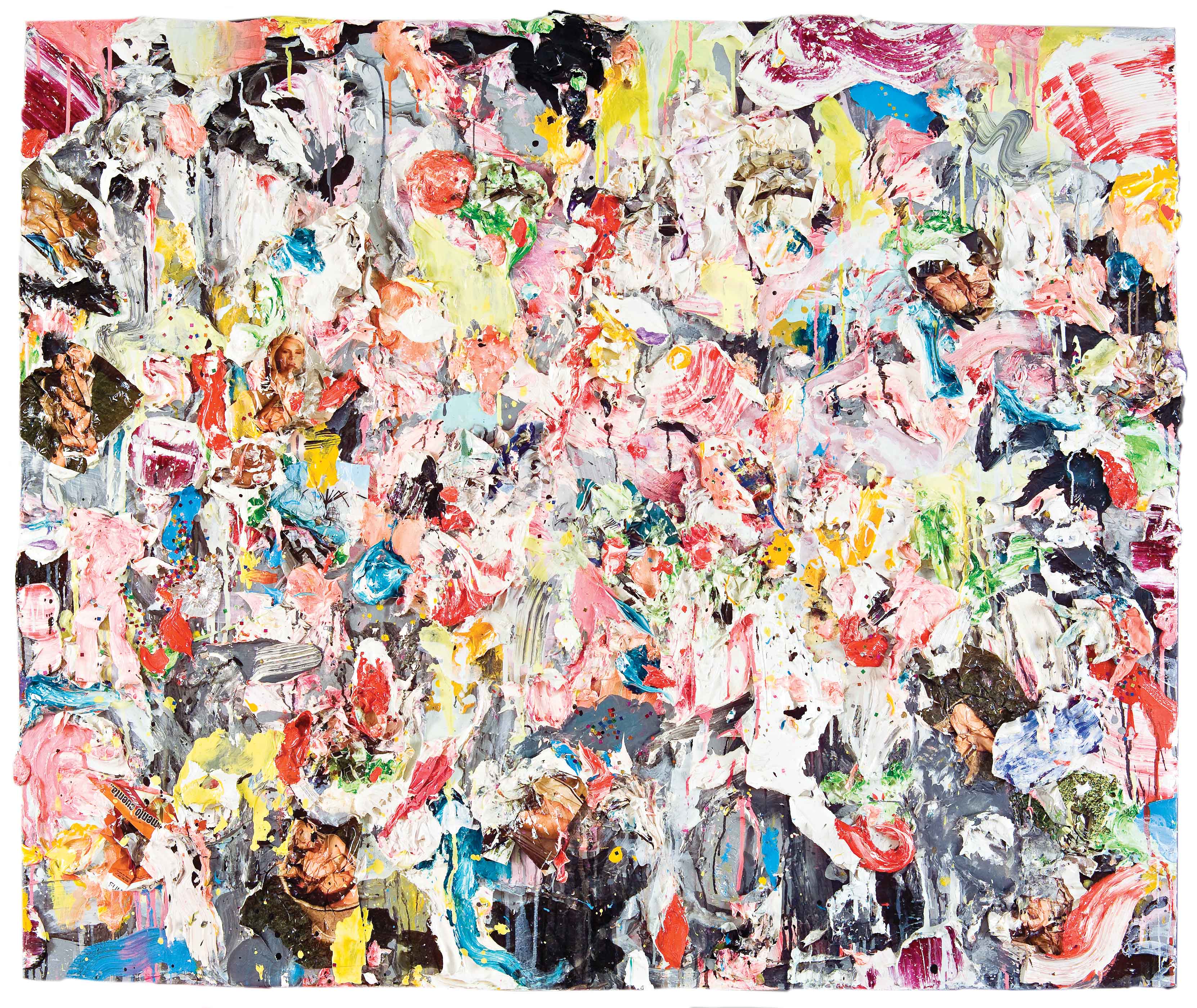

Melvin Martínez, Milky Way, 2011, mixed media on canvas, 80” x 83”. Courtesy of Melvin Martínez and Yvon Lambert, Paris.

From color-field painting through happenings to minimalism, a great deal of the American and international art of the last fifty years has been expressly or implicitly based on an interpretation of the consequences of Pollock’s work, particularly his all-over, poured paintings of 1947-50. By now, one would have imagined these issues to have been completely played out. “History is bunk,” declared Henry Ford, and sometimes our approach to art history can be just as shortsighted. But Pollock’s work is still alive-not yet entirely reduced to fodder for antiquarians-and the proof of it lies in the work of one of the best young painters of the moment.

Just so: Offering something substantially new in painting, Martínez at the same time shows us a new Pollock, one we may not have seen before, and therefore opens up new possibilities for painting in the future. That’s a heavy responsibility to place on the shoulders of such a young man, someone might admonish me. But it’s not my fault, would be the reply; Martínez has already taken it on himself, perhaps in all innocence, but now it’s up to him to handle it.

For Allan Kaprow, influenced by Harold Rosenberg’s essay “The American Action Painters” and Hans Namuth’s Life magazine photographs of the painter at work, the upshot of Pollock was the performative aspect of artmaking-art as process, as event. For the critic Clement Greenberg, on the other hand, Pollock’s lesson had to do with unity and opticality, and would lead above all to the stain paintings of Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis; Donald Judd followed Greenberg’s lead but substituted materiality for opticality, citing as the radical and forward-looking qualities in Pollock’s work its “large scale, wholeness and simplicity” and the fact that “the dripped paint…is dripped paint…not something else that alludes to dripped paint” (195).

BETWEEN OPTICALITY AND MATERIALITY

In their energy and (usually) their all-overness, the paintings of Martínez surely take their cues from Pollock, more than from any artist in between; but they remind us that they need not and should have to choose between Greenberg’s opticality and Judd’s materiality. For Martínez, these seemingly opposed qualities are one and the same. For it is the material density of the surface, the outrageous tactility of them, that dissolves all sense of immutable form and sets color afloat. If Martínez’s paintings possess a radiance, a refulgence that has not often been seen in painting since certain masterworks of Pollock’s, such as the aptly named Lucifer (1947), it is precisely because he sets his colors clashing against each other with a brash vibration that prevents the eye from ever pinning them down to a single spot. Here, the opticality of color is entirely congruent with the materiality of the surface, in which not only is pushed and dragged and churned-up paint exactly that, but all kinds of heterogeneous materials like glitter and artificial flowers and plastic bows are exactly and only what they are, too-all the while adding their own particular notes to the great clashing chord of the painting’s color. One has seen materials like these before, to be sure-for instance in the “Pattern and Decoration” art of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and then in certain species of East Village art that were influenced by P&D; but Martínez uses these gaudy materials in a way that is precisely not decorative, not ornamental, nor as primarily evocative of any particular subject matter. He uses them in a completely painterly way, as the artificial flesh of color. He displays them and dissolves them in one and the same gesture.

Collage # 4, 2011, mixed media on canvas, 72” x 60". Courtesy of Melvin Martínez and Yvon Lambert, Paris.

But brilliant as Martínez’s color may be in its synthesis of tactility and opticality, there is an even more original aspect to his reinterpretation of Pollock. Greenberg and Judd may have differed over opticality and materiality, but they agreed on one thing: the unity, uniformity, wholeness, and simplicity achieved in his all-over paintings. This view was certainly shared by painters like Barnett Newman or Morris Louis or Frank Stella or Brice Marden and sculptors like Judd or Tony Smith. The new art, they were all certain, would be an art of singleness and unity in which the part would be assimilated to the whole. Yet a glance at nearly any Pollock painting-at least, a glance taken after one has seen a Martínez painting-shows that his practice had nothing in common with such an approach.

Look at Pollock and you are immediately, insistently aware that you are being affected by a multitude of marks and gestures that have been woven together, a tangled web, in this marvelous unity. A Pollock is not simple, as Greenberg and Judd would have it; on the contrary, it is dauntingly complex. It is precisely this multiplicity, this microscopic level of sensation, which has been missing from most of the painting (and the sculpture) that has developed out of Pollock’s direct legacy. (Perhaps some of the performative derivates, those following from Kaprow’s branch of Pollock’s lineage, have retained something of this complexity.) Martinez brings this richness, this density, this infinitesimal level of detail back to abstract painting. Perhaps it is only through the experience of his work that we begin to realize how much we’ve been missing this pictorial opulence.

PAINTINGS TAKES A CLOSE-UP

But what about the paintings Martínez makes that use an isolated form against a more or less uninflected surround? Doesn’t this reintroduce the figure/ground dichotomy that all-over painting did away with? Well, yes and no. Because if you look at the densely painted central areas of these paintings-or painted and collaged, as in Milky Way (2011)-you won’t find a figure; that is, you won’t find a defined form. Instead you will find a concatenation of paint-events that, however they impact each other, do not combine to form a shape. Each mark retains its own identity, and never becomes part of a description of some greater whole. I notice that one of these paintings, from 2010, is called Portrait, and it is as if Martínez had decided to silhouette a segment of one of his all-over paintings in order to present a sort of portrait of his mark-making-of the kinds of painterly activity that go into the making of his all-over fields. So despite appearances, the same logic of the all-over applies here-he has merely elected to analytically separate the support in order to highlight some of the separate components of what would have been the larger field. The paint itself is taking its close-up.

Portrait, 2011, mixed media on canvas, 36” x 42”. Courtesy of Melvin Martínez and Yvon Lambert, Paris.

Because of its complexity of structure, resolved into an all-over coloristic accord, Martinez’s painting contains a complexity of feeling that has been rare in recent abstraction. Here we find sensuality and humor, tenderness and aggression, boldness and sensitivity, ardor and skepticism-each emerging from moment to moment as a distinct but transitional material sensation. The abstraction of these paintings constitutes a refusal to submit these sensations to a story with a beginning and an end. We remain at liberty to enjoy them as they come-as long as we have the stamina, for these sensations are strong. In this, Martínez has changed the past of painting and will affect its future. That’s why Martínez matters.

WORKS CITED

- Borges, Jorge Luis. Selected Non-Fictions. Ed. Eliot Weinberger. Trans. Eliot Weinberger. New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

- Judd, Donald. Complete Writings 1959-1975. Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975.