« Related Readings

Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe

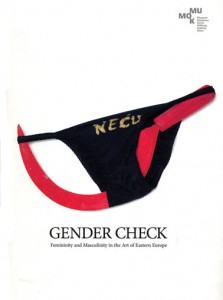

Bojana Pejić (ed.), Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe. Cologne: Walter König, 2009. ISBN 9783902490575

Bojana Pejić (ed.), Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe. Cologne: Walter König, 2009. ISBN 9783902490575

By Mirjam Westen

In 1968 Polish artist Maria Pininska-Beres made “The Psycho Furniture” series, soft organic formed sculptures in pink colors, arousing an air of joyful and erotic femininity. Her compatriot Natalia LL challenged around the same time the voyeuristic gaze by representing herself in autoerotic scenes in her series “Consumer Art.” Can one imagine what these works meant in countries where communist parties had for a long time adhered to a social realist art doctrine that glorified images of muscular women and men as heroic workers striving for the collective goal, and propagated equality but effectively erased sensuality in visual representations? Conceptual, abstract, and poor art did not amuse officials in some countries, and Ukrainian photographer Boris Mikhailov lost his job as an engineer in the 60s after the KGB found pictures of un-heroic nudity, such as his wife showing her bare buttocks while walking through a fallow field.

These are just a few examples of the more than 200, mostly female, artists who were researched by curator Bojana Pejić for her huge exhibition and catalogue Gender Check: Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe (shown in Vienna and Warsaw 2009-2010). The project was realized through the ERSTE Foundation, who commissioned it on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the revolution in Eastern Europe. Pejić, along with a team of experts from 24 different countries, selected for the exhibition over 400 works. The research starts with the 60s, when most of Soviet states experienced the end of Stalinization, and ends with the recent period, thereby covering almost fifty years, ironically summarized by Pejić as a development “from equality without democracy to democracy without equality.” Instigated by gender and manifold feminist issues, Pejić scrutinized art from before ‘die Wende’ and after, official and nonconformist art, art by well-known and lesser-known artists, by (abstract) modernists, conceptualists and contemporaries (who can be anything nowadays), demonstrating that “in the period of state socialism, there were various and sometimes contradictory conceptions and visual representations of femininity and masculinity.”

One of the striking contradictions put forward in the catalogue are the schizophrenic effects of a culture that formally advocates gender equality-it did cut back gender-based economic discrimination-while remaining patriarchal and sexist at the same time. In Gender Check, art from various disciplines and countries, themes (such as self-portraits, portraits of friends, motherhood, the body, nudity, and the role of women in artists’ groups), and (alternative) cultural infrastructure are re-interpretated from many angles and, most valuably in my opinion, contextualized in their own local, historical, artistic, and political settings.

With the catalogue, which unfortunately lacks an index, Gender Check, turns the past with all its contradictions into a productive field for new generations. Hopefully it will empower them to stand up against-as Pejić observes critically-the new socio-political conditions that nowadays put forward the “re-feminization and domestification of women, and the aggressive re-masculinization of the public sphere.”

Mirjam Westen is curator of contemporary art at the Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem (MMKA) in The Netherlands.