« Features

My Work is a Reaction to the Idea of the Latin American Artist. An Interview with Oscar Santillan

By Robin van den Akker

In March 2015, Oscar Santillan hiked to the top of England’s highest mountain, Scafell Pike, and removed its tip. The tip was the focal point of the installation The Intruder (2015) that was on display in Santillan’s first U.K. solo exhibition at the Copperfield Gallery, London1. It is a tiny rock. A one-inch stone, in fact. Yet in the British popular imagination it has taken on immense proportions after public outrage turned into media frenzy (or the other way around, of course). Tabloids, broadsheets and, yes, even the BBC endlessly recycled accusations of vandalism and thievery whilst avoiding–or unwittingly circling around–questions concerning national pride and regional identity, natural conservation and cultural geography, as well as any critical engagement with the work itself.

Oscar Santillan (born in 1980) is South American by way of Europe. Born and raised in Ecuador and living and working in London and Amsterdam, he once described his oeuvre as a reaction to the idea of the Latin American artist. The Intruder is the most recent addition to a body of work that set out from being a very direct commentary on the social conditions and political tensions in the Americas, but by now encompasses highly speculative yet subtle inquiries into our conventional conceptions of historical time and the mundane relationships between humans and animals, subjects and objects.

We recently met to discuss these, and other, aspects of his work that have been absent from the coverage of “Scafell Pike” and in the midst of the demands—and I kid you not—to return its top.2

Robin van den Akker - What do you mean when you say, ‘My work can be seen as a reaction to the idea of the Latin American artist?’

Oscar Santillan - A prominent part of the art produced in Latin America is instrumental to what I called ‘the temptation of reality.’ Often the first impulse of artists in conflicting social conditions is to react to those conditions. Latin America is one of those parts of the world where the social dynamics are so strong, so obscenely visible, that often artists give in to confronting that immediate layer of reality, while discarding other potential scenarios and corners of reality. The artist, then, sees himself as a citizen, or, I should say, as an anxious citizen, who is sucked into a grid of preexisting categories and narratives that attempt to tell us where the world starts and ends, what is possible and impossible. There were moments in the recent history of Latin America in which that confrontation demanded inventiveness and courage. There is powerful political art in the continent, art made in the most ferocious conditions. But through time it has become too academic, too safe and politically correct. A moralizing postcard. It is often said ‘everything is political,’ but I do not believe it since there are areas of reality, potential realities as well, which are absolutely untouched by those concerns.

Oscar Santillán, The Intruder, The highest inch of England on a pedestal, 2015. Installation view. Courtesy of Copperfield Gallery, London.

R.V. - What about yourself? Did you ever–at any moment in your career–succumb to this temptation of reality?

O.S. - At the very beginning of my career I tried out some very abstract exercises, such as my first solo show “Art for Dogs” (2002), an exhibition in which only dogs were welcomed in. The content of the show was undisclosed, and people would have to wait outside while their dog would explore the exhibit. But soon after my political concerns took over, washing out the inquiries I was developing. During that period my work was strongly related to History and its present consequences, or what I see nowadays as a conservative view of the present: the present as a mere prolongation of the past. Anyway, those were really tumultuous times in Ecuador, the political left and the social organizations were in the streets protesting and resisting, and as many other young people did, I became a militant.

R.V. - How was this militancy translated into your art practice at the time? Can you give an example?

O.S. - My work of that period deconstructs and comments on big topics; they are about a world written with capital letters. Works such as Prácticas Degeneradas (Degenerated Practices, 2005) and Prolongación (Prolongation, 2007) are perfect examples of that way of working. The first one is a large mass of solid oil paint modeled after Colonial imagery and represents a self-castrated boy. The second piece was part of my work within Lalimpia collective, formed by self-taught artists, and is an installation that explores the promises of the oil-dependent economy of Ecuador. In both cases, the concerns move around topics of national history and power understood in its more evident way.

R.V. - So what made you reconsider this ‘Latin-American mode?’

O.S. - The left won the elections in 2006, and the language we used to understand and criticize our reality became the official discourse. It became the language of the ruling class, yet they turned it into shameless jargon. The moment critical discourse was taken into the territory of real politics I did not know where to position myself. Many of my friends who were among the most lucid critical voices in the country started to work for the government, which initially was formed by a coalition of the new left, indigenous organizations, ecologists and intellectuals. At the beginning so many of us were hopeful about the promised changes, and indeed several of those changes have taken place, but often including second agendas aimed to secure the permanence of this new ruling class. Coincidentally at the time I was reading Deleuze’s Cinema 2: The Time Image, and his differentiation between the mirror image and the crystal image struck me. It helped me to realize where to position myself: It was outside of the mirror image, outside of any loyalty to the immediate reality. So I turned away from those big discussions towards the territory of existence.

Oscar Santillan, Prolongation, 2007, fuel pump and a 1,3 Km long hose. Work in collaboration with Lalimpia collective. Installation view at Havana Biennial 2007. Courtesy of Lalimpia, Ecuador.

R.V. - Existence?

O.S. - In The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera makes the distinction between ‘reality,’ or what does not need to be demonstrated, and ‘existence,’ which is the territory of possibilities. For me this means narrowing down the scale of the world as I used to see it in search of lost corners or hints of the future. By narrowing down the scale of the world I am pointing to a sense of ethics, to what theologian Leonardo Boff calls ‘the dimension of carefulness,’ to care for what is overlooked, to care for what is neglected, and I would say to care for what does not even exist. It is a sort of pre-modern mindset in which all categories are negotiable. It means working at the edge where noise and knowledge fold together, the edge where facts and fiction fold together. So after 2006 I went back to my previous concerns and some newer ones that I had put on hold during those previous years.

R.V. - What kind of concerns-both older and new?

O.S. - The old concern that I returned to explore is the relationship between animals and humans, or in other words, the possible relationships among mammals. From “Art for Dogs” (2002) I reconnected with those concerns with Memorial (2008), The Manifesto of Goodness (2012), La Clairvoyance (2012), which is a work that introduces a newer concern in my practice, namely the way we look at the world, and the mechanisms of vision that are present in obsessive works such as The Permanent Blink (2010) and All the Eyes of the Universe (2012). And another concern or strategy I am currently developing consists of connecting what is unconnected: a marble sculpture to a cloud, in Cloud (2012); Carl Jung to jaguars, in Zephyr (2014); trance dance to Friedrich Nietzsche, in Afterword (2015); and bird sounds to karate, in The Whisperer (2015). These later works are aimed to insert a meaningful narrative where there was none. They insert a sense of possibility where no possibility was even needed.

R.V. - About this relationship between humans and animals or mammals, it seems that you engage with these relations beyond some kind of Nature/Culture divide by incorporating domesticated animals such as a cow, a horse, a cat, dogs, etc. What kind of other possible associations do you want to investigate, other than the association between pet and master, property and owner?

O.S. - Nietzsche has an interesting view on this topic. He makes a distinction between culture and civilization rather than culture and nature. Culture admits, welcomes and celebrates animality; while civilization is the taming of animality. So I try to reframe this well-known dichotomy in our understanding of reality and look at the relationships in those terms.

So far I have mostly worked with animals that live closely with humans. So they are used to human presence and there is an actual historical bond there. We tend to see the relationship between animals and humans—and taming and breeding—as humans engineering something. But Michael Pollan puts forward the hypothesis that we—humans—are the instruments in a larger interaction in which we are actually, or arguably, instrumentalized by animals in order to provide them with nurture. So we are accomplishing a task that has always already been potentiality there, as a property of animals.

With my work I try to speculate on this. I see my self as a kind of vessel. For instance, in The Manifesto of Goodness, I am an instrument to accomplish a task that connects different mammals. So I position myself in that kind of territory.

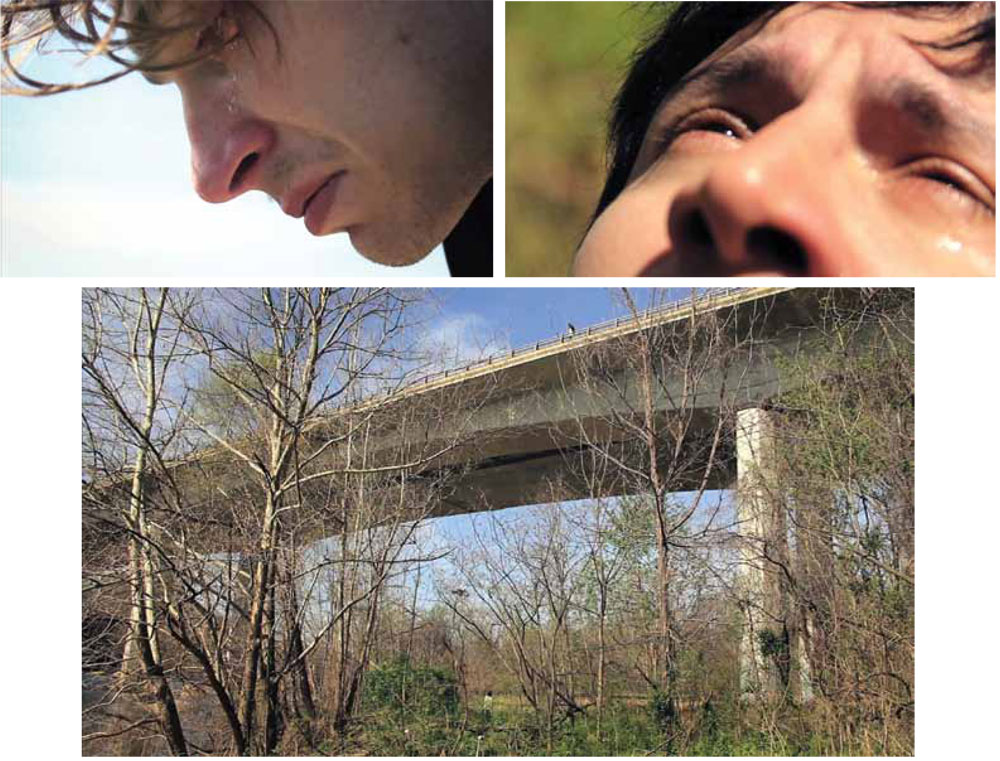

R.V. - The Manifesto of Goodness is structured around a long walk in which you bring cow milk, taken straight from the tit and kept in your mouth, from the cow to a thirsty cat. Could you elaborate on the use of body fluids–sweat, sperm, milk, tears-as a medium of connection in many of your works?

O.S. - There is a certain tension in these materials. They are still part of the body that secreted them. They show the metamorphosis continuously happening within the body of mammals but are often not manifest in the relationship between mammals.

R.V. - So does your work attempt to cultivate the relation between humans and animals rather than civilize, and therefore deaden, some sort of animal spirit or animality within animals and humans?

O.S. - Yes. This is extremely interesting, especially in light of the connection to Nietzsche’s ideas on forgetfulness and forgiveness. He talks about animals as beings that are able to move forward because of their capacity for forgetting. And he talks about not-forgetting-but-forgiving as part of the weakness of civilization. Yet at the same time the question of animal consciousness is often surrounding my work. The question: ‘Who is there?’ Think of Clairvoyance. It’s simply a picture of a horse, but a horse arguably reflecting on himself.

R.V. - Do you mean as some kind of individual?

O.S. - I wouldn’t be afraid to speculate about, or even say that, animals—or at least mammals—have traces of individuality. Yet we should criticize the idea of the individual as some kind of product of the Enlightenment. I don’t think we can come up with such an understanding of the self in our historical period.

R.V. - Earlier, you mentioned the notion of a ‘pre-modern mindset’; here, you criticize the ‘Enlightenment’ conception of the self. Could you say that your work engages with the Latourian idea of a non-modern, symmetrical relationship between subjects and animals-as-objects by ‘subjectifying’ animals and ‘objectifying’ yourself?

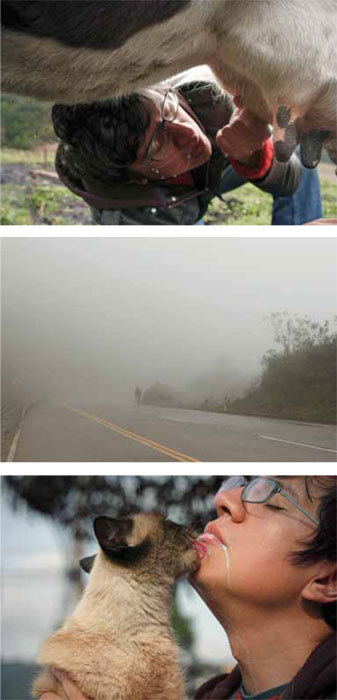

O.S. - I would say that is at the core of many of my works, yeah. But it also extends to relationships between humans. In the case of The Telepathy Manifesto, for instance, there is an inequality in pain and suffering, yet I try literally—even though it is absurd—to equalize the relationship between the person who feels the pain and the person who doesn’t. The paradox is that while all these hierarchies get moved around and get rearranged in all kinds of new constellations, I actually make sense out of them, somehow. In that regard, I do not follow the arguably postmodern way of dealing with that problem.

R.V. - Is this where your inquiry into a sense of purpose comes in? To me, your works contain a strong sense of purpose. There often is some kind of relatively simple task or physical activity at hand that needs to be carried out in a very direct manner.

Oscar Santillan, The Telepathy Manifesto, 2011, event documented on video. Courtesy of Copperfield Gallery, London.

O.S. - I am very interested in the idea of a sense of purpose. To get purpose you need to speculate about the meaningful relations among things. You can’t just spread them around and leave them like that. So in the end I try to create a string that allows me to move from A to B and gives direction, and no matter how absurd the connection is, it is meaningful.

R.V. - So do you aim to look anew at all kinds of associations to not only draw out and deconstruct the hierarchies and categories imposed by our conventional ways of thinking but also to speculate about and reconstruct more symmetrical relationships?

O.S. - I would say so, yeah.

R.V. - In A Hymn (2013), but also in works such as The Telepathy Manifesto (2011-2012) and Accompaniment for a Falling Leaf (2012), the medium of cultivating relations is focus or concentration. Why this use of ‘close attention’ as a trope?

O.S. - I am searching for the power unleashed in small things. In this quest I got rid of metaphors by moving to the ‘things in themselves,’ which of course is a problematic premise since we all experience the world through the mediation of our senses, perceptions and cultural categories. Metaphors are the enemies of small things. Small things are present in front of our eyes but get overlooked. Metaphorical thinking is anxious, it avoids looking at what is here and now since it distracts us with what is somewhere else. I want to focus into what is around me.

Oscar Santillan, The Manifesto of Goodness, 2012, event documented on slides. Courtesy of Copperfield Gallery, London.

A prominent modus operandi of my work consists in generating actual events in the world, which initially are triggered by this careful observation. The works that you mentioned are about humans distilling power in a sort of unknown ritual that is only possible in their proximity. Tiny parts of the human body—sweat and tears are part of our body even if we look at them as independent entities—become the only significant element of the work. The paradox is that my work often enacts a deeper commitment to the physicality of the world but its end result does not belong to the physical causality that seems to surround us.

In A Hymn, the body is shown to a level of maximum exhaustion, and then the consequences of that exhaustion, the drops of sweat produced by the body, become the main focus of what is to come. It is unclear then how the drummer who beats the drum every time a drop reaches the floor can even see them with such accuracy. It is another reality invading the previous one. The same applies for the leaf of Accompaniment. These things do not belong to meaningful categories; when they are out in the world they can be seen as noise: one more drop of sweat on a sweaty person, one more leaf in a forest, but somehow the context of their existence is reframed in the event showing that they carry meaningful information, that they are able to enact a certain power.

R.V. - Could the same be said about The Intruder, which was structured around the tiny rock you took away, or stole, from the highest point in England?

O.S. - The Intruder is also about the distinction between noise and knowledge—what holds information. What is interesting is this idea about small things and where the power of small things is located. This rock has always been noise—because we are not talking about some cartoonish tip—and from one second to the next it is turned from noise into a holder of a whole cultural geography and a landscape of power.

R.V. - This distinction between seemingly insignificant noise and knowledge also seems to play into your critique of the conservative view of History—in which the present becomes a mere prolongation of a past intertwined with modernization—without any real sense of futurity. Is your work also a way of re-investigating history, and re-narrativizing History, from the perspective of noise—seemingly insignificant moments or things that officially can’t have any place in any narrative about one’s personal history or official History?

O.S. - Did it ever happen to you that you have a memory of something that hasn’t happened?

Oscar Santillan, Zephyr, 2014, the breeze of jaguars trapped in a marble container, and a slide projection. Installation view. Courtesy of The Ridder, Maastricht.

R.V. - Perhaps. Yes.

O.S. - These kinds of moments really intrigue me. When we have memories of things that haven’t happened but might have happened and we are sure that they have happened. The first memory I have of my life is a memory that rationally is a fake memory. During the weekends I used to sleep at my grandfather’s. It is a memory of me jumping from one bed to the other. But the distance between the beds is at least two meters and I was about four or five years old. It cannot have happened. You can take these non-memories of moments in which the rational way of conceiving reality is broken and insert them in reality as a meaningful narrative. Similarly, I am interested in futurity as any kind of possibility that was present in the past as potential and it never occurred. My work Zephyr, for instance, is really a work about futurity, about the future, in the sense that I take an accomplished desire of the past–something that a person wanted to happen but never happened.

R.V. - So in this case Jung’s wish to travel to Latin America, something he never managed to do.

O.S. - Yes. So for this piece I made a sculpture out of a replica of his own, by now lost birth chart, used it as a container to replace a vacuum cleaner bag, took it to the Amazon, asked a shaman where I could find jaguars and used the vacuum cleaner to suck the scent of the jaguar into the sculpture-container. In this way, I accomplished his wishes as literally as possible while trying to find what wasn’t there-that is, this moment of future in the past. And in the case of Afterword, in which I stole a piece of paper from a manuscript of Nietzsche, from the past as it were, in order to go back to that past and speculate about a moment that wasn’t public knowledge, the moment of Nietzsche dancing to reach a state of trance.

Oscar Santillan, Afterword, 2015, a piece of paper belonging to Friedrich Nietzsche, a slide projection, two prints, and a video projection. Installation view. Courtesy of STUK, Leuven. © Pierre Antoine.

R.V. - This brings us back to the Deleuzian notion of the crystal image and a multilayered reality, right?

O.S. - Yes. For Deleuze, the crystal image entails an interaction of the actual and the virtual, ‘resulting,’ if that’s the correct word, in a multilayered apprehension of time and a multi-modal production of temporality. Another way of saying this would be by using the notion of sparks, small sparks that contain meaningful narratives. These sparks do not aim to confront or replace the mainstream narratives about reality—or the real—in itself. Rather, they are aimed to last for a second before they vanish. So what interests me about the spark is that it shows the potential of how things could be, whilst avoiding creating a new system that replaces an older system.

NOTES

1. “Oscar Santillan: To Break a Silence into Smaller Silences” was on view at Copperfield Gallery, London, from March 26th through May 9, 2015.

2. For further reading on ‘Scaffel Pike’-gate, see:

<http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-cumbria-32053132>

Robin van den Akker is a cultural philosopher working at Erasmus University College Rotterdam and is co-coordinator of the Centre for Art and Philosophy there. He has written about contemporary aesthetics and culture and the digitization of everyday life for, among others, the Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, Frieze and Monu, and acted as advisor for various art exhibitions and cultural events about metamodernism. With Timotheus Vermeulen, he is working on two books on metamodernism and organized the symposium Metamodernism Marathon (Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 2014).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.