« Features

Once More, with Feeling. Feminist Art and Pop Culture Now

By Maria Buszek

The inelegant but exceedingly apt term “authenticism” has been making the rounds in cultural criticism as of late, relating to a permutation of postmodernism evident in emerging artists’ reclamation of emotional, personal themes in their work. Fed up with the jadedness, irony and mean-spiritedness of much late postmodern art, it seems as if artists are instead returning to the era’s origins-in particular, eschewing the notion of a single, narrow “trajectory” of a dominant avant-garde discourse-and embracing the ideal of an open, polyvocal, often autobiographical approach to art making. As writer Edward Docx put it in a piece about this moment in The Prospect, the “theatrical, skin-deep, kitsch” effects of postmodernism seem today to be increasingly replaced by a return to the movement’s deeper lessons, which have made us “more comfortable with the idea of holding two irreconcilable ideas in our heads: that no system of meaning can have a monopoly on the truth, but that we still have to render the truth through our chosen system of meaning.” The result, Docx argues, is a burgeoning generation of artists who look to their experiences and communities to produce “something complex and intelligent and telling and authentic and well-written about [one's] own time.”1

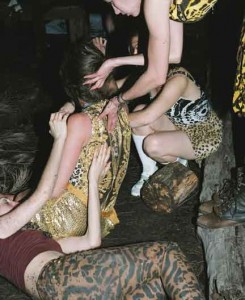

Perhaps inevitably-as originators of the phrase “the personal is the political”-the feminist artists among them have embraced this sensibility in their explorations of the emotional and affective. These explorations are literal in the photographs of Naomi Fisher. Based in Miami, where the sensuous, wild natural environment famously serves as the backdrop to the population’s tendency toward artifice and materialistic excess, Fisher frequently explores this culture clash in her work, through the lens of feminist writers such as Hélène Cixous and Kathy Acker, and with fever-dream strategies derived from Surrealism. In her 2009 exhibition “The Brave Keep Undefiled, A Wisdom of Their Own,“ Fisher exhibited a series of photographs and paintings derived from an all-female camping trip at Florida’s Oleta State Park, in which she and several friends camped for days swathed in layers of vintage Versace couture that the artist stumbled upon in garbage bags at a storage-garage sale. As seen in photographs such as Hold Her Up, the women doze, dance, traverse the wilderness, and cook over open fires in the primordial environs of this island park, clothed in the signature, sexy, excessive Versace fashions that they, naturally, proceed to muddy and tear apart in the action. In all these photographs, Fisher’s images of young, lovely and stylishly clad women engaging in puzzling, violent and often comically savage behaviors call to mind the complex relationship Surrealist women such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Frida Kahlo and perhaps especially Léonor Fini expressed about nature, domesticity and fashion in their work and lives-a love-hate relationship that young feminists share with such 20th-century predecessors, but in a way particular to 21st-century feminism.

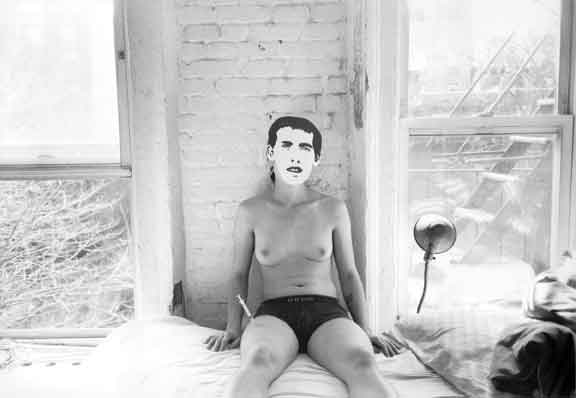

Emily Roysdon, Untitled (Needle) from Untitled (David Wojnarowicz project), 2001-2007, silver gelatin print, 11”x14”. Courtesy of the artist.

I find it telling in the context of “authenticism” that Fisher makes much of the fact that she was born the same year that Cixous wrote her essay “The Laugh of the Medusa,” in which she famously wrote: “Women must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their own bodies. Women must put herself into the text-as into the world and into history-by her own movement. [...] Write your self. Your body must be heard” (Cixous 627, 630). Fisher argues that Cixous’ call for women to write their own experience is still necessary today because, “I want to make sense of this world, but I understand that there is no way to know what the unique situations and experiences of all people are unless their stories are actively sought after and honestly expressed.” And, like so many younger women who embrace the term, Fisher still identifies with feminism because it remains “impossible to pretend that the world is no longer hostile towards women,” regardless of the successes of feminist generations before her.2 Still, as cultural historians Joanne Hollows and Rachel Moseley have argued, unlike previous generations, for whom there had always been an “outside world” that those inside the feminist movement were invested in challenging and infiltrating, those growing up after women’s liberation set Western culture on fire in the late 1960s “never had a clear sense of, or investment in, the idea of an ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ of feminism” (Hollows and Moseley 2). Feminism could be, and often was, just about everywhere.

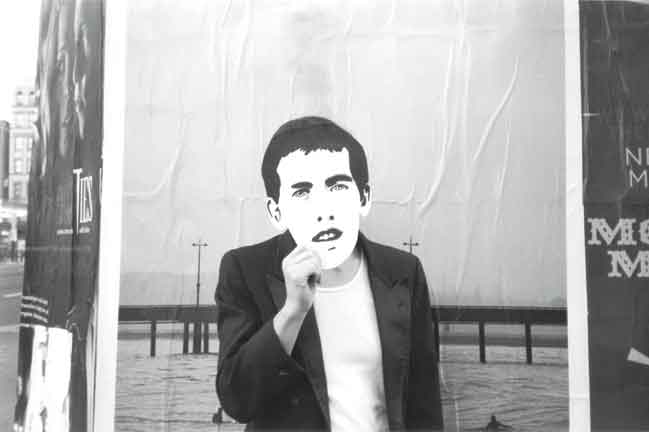

Emily Roysdon, Untitled (Pier) from Untitled (David Wojnarowicz project), 2001-2007, silver gelatin print, 11”x14”. Courtesy of the artist.

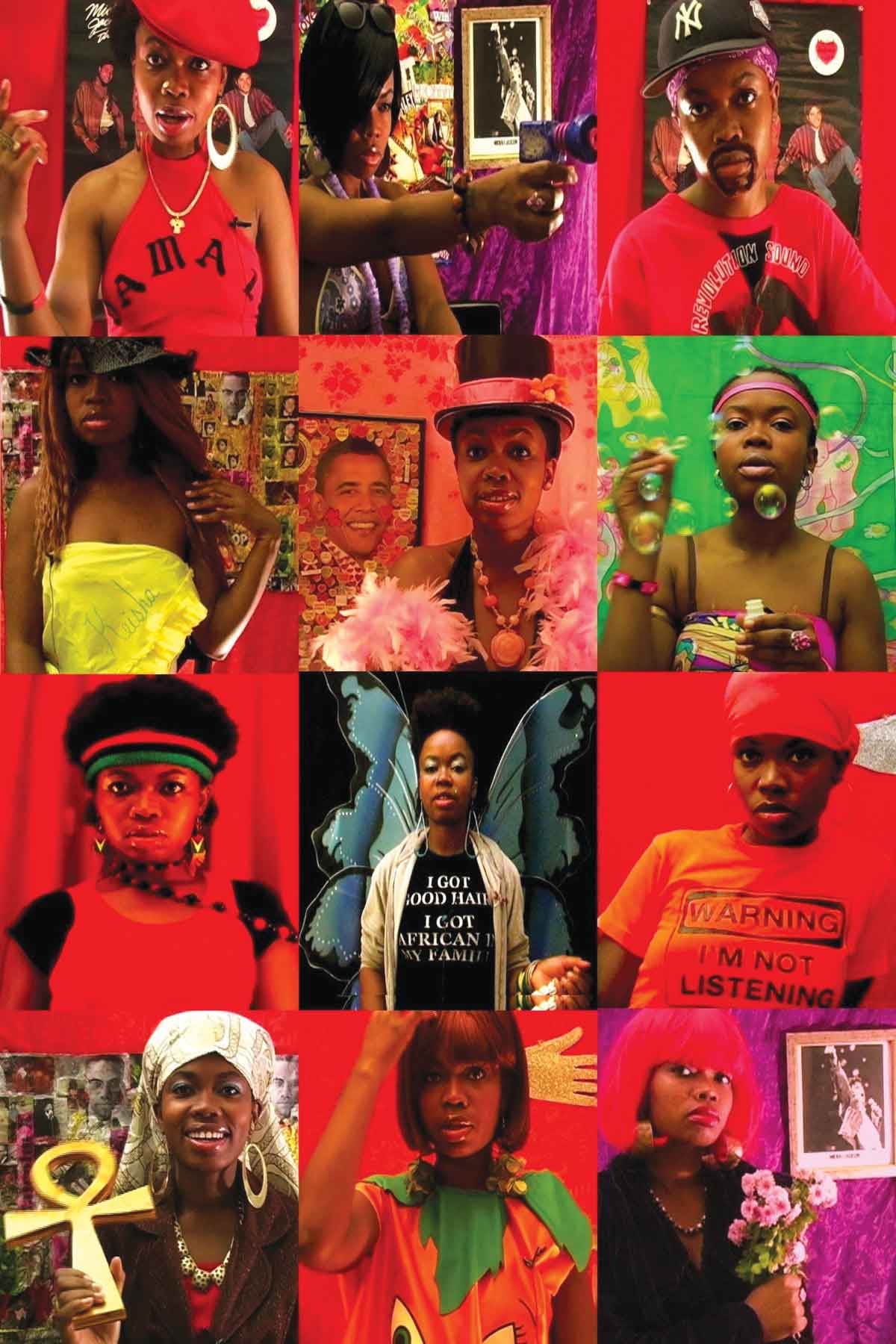

And it is in the realm of pop culture that one arguably finds the most visible, vibrant and persuasive reflections of emerging feminisms today: Esteemed Web journals such as Slate have featured columns dedicated to feminist issues and authors; online communities such as Feministing, Crunk Feminist Collective, Jezebel, and Feministe burn up the blogosphere with conversations about feminism’s continued relevance in entertainment as well as politics; prime-time network series, including 30 Rock, Parks and Recreation, and Scandal, are not only helmed by feminist writers, producers and actors, but the shows themselves center on self-declared feminist characters who initiate often sophisticated plotlines about current events; musicians like Peaches and M.I.A. mine, sample and critique music history in song, often paired with videos that might rewrite The Wizard of Oz as a lesbian revenge story, or mock the Saudi ban on women drivers; and The Daily Show’s “Senior Women’s Issues Commentator” Kristen Schaal and Current TV’s Sarah Haskins and Erin Gibson call out sexism in the media on popular cable shows. Small wonder that artists like damali abrams-whose ongoing video diary confronting her experiences of racism and sexism takes its title and style from the “self-help TV” of talk shows-look to the power and potential of mass media, even as they use it to recognize and critique the dominant messages usually found there.

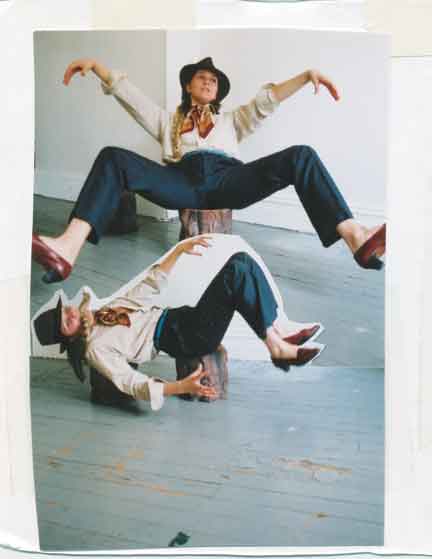

K8 Hardy, Fashionfashion, Issue 4, page excerpt from artist zine, 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Reena Spaulings Gallery.

Indeed, for many emerging feminist artists popular culture presents itself as its own “medium”-one that on the surface seems familiar and reassuring but baits and switches audiences into an awareness of the feminist potential, an oppositional re-reading of the original, and sometimes both at the same time. In relation to the work of the self-described “genderqueer feminist collective” LTTR, art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson approvingly defined this practice as one of “critical promiscuity” generating unexpected connections across genres and media as well as the generational, ethnic, gender and sexual identities of the artists who contribute to them3. These strategies were on view from the first issue of the collective’s ‘zine in 2002 (”distributed” in print and online)4 with a cover from co-founder Emily Roysdon’s Untitled (David Wojnarowicz Project), in which the artist reconceives Wojnarowicz’s famous Rimbaud in New York series of the late 1970s-replacing the latter’s use of a cheap, photocopied Rimbaud “mask” with one of Wojnarowicz’s face-using scenes from the life of a similarly audacious, thrill-seeking 21st-century woman. This cover’s image of the series’ model sprawled luxuriantly on a rumpled bed “masturbating” her strapped-on dildo is gloriously discombobulating on lots of levels and anticipates what Roysdon would articulate in a 2009 essay as a form of “ecstatic resistance,” in which returning to the messy, queer, street-level, corporeal and always-personal postmodernism of forebears like Wojnarowicz might allow artists to “re-imagine what political protest looks like. And what it feels like.”5

damali abrams, Autobiography of a Year, 2010, video stills from four-screen video installation. Courtesy of the artist.

Roysdon’s concept foregrounds desire and sexuality as crucial strategies of resistance-a fact that is similarly, explicitly foregrounded in the work of fellow LTTR co-founder K8 Hardy and contributors Eve Fowler, A.L. Steiner, and A.K. Burns, all of whom have used variations of what Steiner and Burns have called underground “1970’s porn-romance-liberation films” as models for messy, sexualized projects in which bodies of a wild range of sizes, genders and sexual orientations aggressively run amok. But LTTR’s members have also used their bands, poster projects, workshops and sit-ins as media for exploring the political possibilities of feminist pop-cultural influence. With Hardy’s ‘zine Fashionfashion and much-reported-upon, recent runway show as part of the 2012 Whitney Biennial, even fashion-derived from dumpsters and thrift stores, spectacularly repurposed in body-distorting, gender-bending costumes, and defiling the pristine aesthetic with models who leak menstrual blood through lingerie-has been invaded as a site of possible, even logical feminist infiltration.

That feminism arguably expresses itself these days so tangibly in art that connects to pop culture, and vice-versa, seems relevant to me as both a feminist and an art historian. It is a profound reflection, if I may return to paraphrase Hollows and Moseley, of what it means for feminist thought to have evolved into a generation of emerging artists without “the idea of an ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ of feminism.” And such popular expressions of feminism reveal the pressing need for feminist scholars willing to address the power of pleasure-their own included-as an authentic activist strategy. My hope is that a parallel feminist art scholarship emerges that might speak to this work-to what it looks like and what it feels like-with the same sense of humor and audacity.

WORKS CITED

- Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” in Feminism-Art-Theory, edited by Hillary Robinson. London: Blackwell, 2001. Originally published in Signs 1, no. 4 (1976): 875-893.

- Joanne Hollows and Rachel Moseley, “The Meanings of Popular Feminism,” in Feminism in Popular Culture, edited by Hollows and Moseley. London: Berg, 2006.

NOTES

1. Edward Docx, “Postmodernism Is Dead” The Prospect online (20 July 2011)

<http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/postmodernism-is-dead-va-exhibition-age-of-authenticism/>

2. Naomi Fisher, artist’s statement from Caribbean Contemporary Arts (CCA), Big River Workshops. <http://www.cca7.org/workshopspages/bigriver.html>

3. Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Repetition and Difference: on LTTR,” Artforum 44, no. 10 Summer 2006: 109.

4. LTTR’s ‘zines, attendant new-media projects, and other activities are available and archived at < http://www.lttr.org/>

5. Emily Roysdon, “Ecstatic Resistance,” C Magazine: International Contemporary Art (Winter 2009): 15.

Maria Elena Buszek is associate professor of art history at the University of Colorado in Denver. Her recent books include Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art (2011) and Pin-Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture (2006), both published by Duke University Press. She has contributed to numerous anthologies and exhibition catalogs, as well as scholarly journals such as Art Journal and TDR: The Journal of Performance Studies.