« Related Readings

Rebelle: Art & Feminism, 1969-2009

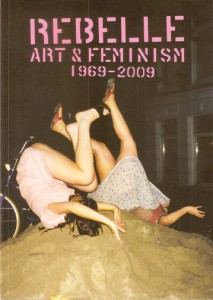

Mirjam Westen (ed.), et al. Rebelle: Art & Feminism, 1969-2009, Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem (MMKA), Arnhem, 2009-2010. 352 pages. ISBN 9789072861450

Mirjam Westen (ed.), et al. Rebelle: Art & Feminism, 1969-2009, Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem (MMKA), Arnhem, 2009-2010. 352 pages. ISBN 9789072861450

By Paco Barragán

After the exhibition “Rebelle: Art & Feminism, 1969-2009″(held at the Museum voor Moderne Kunst in Arnhem (MMKA), The Netherlands, May 30 - August 23, 2009), this book-catalogue appeared with essays showcasing 40 years of feminist art history in The Netherlands: women’s art movements, the role of women in the Dutch Visual Arts Foundation, exhibitions with feminist art, and networks and initiatives of female artists. The exhibition displayed works not only from Dutch artists from early practitioners (like Lydia Schouten, Diana Blok/Marlo Broekmans, and Klaar van der Lippe) and younger artists (like L.A. Raeven, Risk Hazenkamp, or Jeanne van Heeswijk), but also from many international artists (like Marina Abramovic, Nezaket Ekici, Regina Galindo, Sarah Lucas, Sophie Calle, Tracey Emin, Valie Export, Mona Hatoum, Lida Abdul, Cheng Lingyang, and Nancy Spero), totaling 88 artists.

As Mirjam Westen, editor and curator of the show, keenly points out in her introductory text, “the concept feminism is often regarded ambivalently,” because still today “negative attitudes towards feminism still persist.” And, Westen continues, “from the nineteen-eighties onwards, in the United States and Europe, feminism became increasingly viewed as an anachronism.” I think that Westen is basically right as what underlies these negative attitudes and affirmations is a power struggle that stems from the very heart of liberal capitalism and its patriarchal-macho roots.

In addition to the artists’ entries (with information on the artists and their work included in the exhibition) and Westen’s introductory essay, the book-catalogue contains six critical texts: N’Gone Fall’s “Crossing the red line”; Riet van der Linden’s “Touchy Subject: Reminiscences of the women’s art movement of the 1980s”; Ingelies van der Meulen’s “Feminist art: an (un)achievable ideal?”; Tineke Reijnders’ “Rebelliousness squared”; Ineke van Hamersveld’s “An undercurrent of activism”; and Suzanne van Rossenberg’s “What could a feminist art currency look like?”

The book gives an interesting view of a country that while nevertheless being considered one of the most progressive in the world, still during the 70s and 80s-as Riet van der Linden remarks in her intense personal diary-”Equal rights did not, apparently, lead to equal opportunities. Women artists were still trapped in an aura of amateurism, despite their professional training.” Her diary reveals in an intriguing manner her own personal story and how the relationship between gender, power, and creativity is still today unresolved. N’Gone Fall’s text on African artists is interesting, although extremely brief, and it reminds us how African artists shifted from decorative arts toward visual arts with a social and political focus. Ineke van Hamersveld’s essay asks a very pertinent and contemporary question: have social networks like the Internet undermined women artists’ common goals, and are they to blame for the invisibility of women artists’ organizations? In Rineke Reijnder’s essay, she discusses the role and contribution of female artists in artists’ initiatives.

Publications like these are important because they help us to question our ‘patriarchal’ society and explain ‘Why’-to use Linda Nochlin’s title-”have there been no great women artists?”

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and an arts writer based in Madrid.