« Features

Permission is a Material. An Interview with Jill Magid

Working in a wide range of mediums including video, performance, installation and writing, Jill Magid creates art that examines the relationship between individuals and the monolithic social and political institutions-both official and informal-that surround and shape us. Many of her works involve a deliberate blurring of the boundary between art and life, and Magid often serves as the main actor in the situations she explores. In this interview, we spoke with Magid about some of her projects, the notions of trust and personal surrender that are so central in many of them, and the ways in which witnessing, intimacy, speech and silence have also played a crucial role in her work.

By Jeff Edwards

Jeff Edwards - Your website (jillmagid.net) contains the following artist statement: “Permission is a material and changes the work’s consistency.” I’m fascinated by the idea of consent as an artistic medium, because it can be both intangible and definitive at the same time. It’s either there or it isn’t, but it can also shift or read ambiguously to different people, and that can radically change the feel of a situation for both participants and observers. How does this play out in your works?

Jill Magid - Permission is not ambiguous. It is the authorization I aspire to gain from the institutional power that I am applying to, seeking access. The process of gaining (or not gaining) consent can be part of the work; other times it is what allows the work to proceed (or, without it, to continue in another direction). I first became interested in gaining permission from the police after I had been hacking into the informational monitors on MIT’s campus. In the performance Lobby 7 (1999) I hijacked one of these monitors and inserted a live feed of myself searching my body beneath my cloths by way of a wireless surveillance camera that I held in my hand. The police were called in, but could not connect the image on the screen with me standing in the lobby, my hand moving beneath my clothes. I became interested in seeing what would happen if I worked with the police instead of against or in spite of them: If the authority was complicit with me, how would that affect the meaning of my actions? Could responsibility and vulnerability be shared? Permission is a pact, a covenant. It binds the institution and me together, and thus has the potential for intimacy.

J.E. - Several of your projects have involved you being controlled by other people, as in the video Trust (2004), in which police CCTV operators guided you remotely through the city of Liverpool while you kept your eyes closed. How hard is it for you to abandon yourself to external control like that and why do you find those kinds of experiences so compelling?

J.M. - The experience of being led blind through the city by a police CCTV controllers (which became the video Trust) was one of the most romantic moments of my life. Letting myself be controlled by a policeman via the camera-letting his eyes, by way of the camera lens, stand in for my eyes-was the most extreme extension of the relationship I’d formed with the CCTV operators (and of that system itself) since arriving in Liverpool three weeks before. The act of abandoning myself to a larger power is one that requires a foundation that I do work to build. It is a risk on both ends, but not a blind one. There is a tenuous trust between the system and myself that we are pushing and testing; this is what I find compelling.

J.E. - What kind of relationships grow over time with the people on the other side of these transactions? Do you ever find yourself controlling your controllers?

J.M. - Of course, but control is fragile. It moves fluidly between the authority and myself. Each relationship is unique: I had a different relationship with the CCTV controllers in Liverpool than I did with the Dutch secret service in The Spy Project, and yet another kind of relationship with my reporter and trainer in Failed States. In each, though, trust is an issue, and one that is never quite resolved: their own towards me or mine towards them. This is where the tension lies.

J.E. - Being alone in a crowd or creating an intimate space with someone else while you’re out in the open are persistent themes in your work, going back at least as far as Lobby 7 and The Kissmask (1999). Can you tell me a little about those works and their influence on your later work, and also about the relation between public and private space in your more recent projects?

J.M. - With The Kissmask I made a tool to be worn by two people simultaneously to both capture and create the awkward moment of a first kiss. In the mask we, the participants, were like mirrors of one another. In Lobby 7 I captured myself through the spy camera and projected my abstracted and naked body, live, back into the public place I was occupying. I think all of my work carries these themes of pulling something foreign or distant closer to my body, and creating a new space for us to share. The works since then create somewhat analogous relationships between institutional bodies such as police, secret services, the media and the U.S. court system and myself.

J.E. - In 2005 you entered into an agreement with the AIVD (the Dutch secret service) to make an artwork for their new headquarters, based on interviews with some of the agency’s employees. One result was Becoming Tarden, a novel that presented a lot of the information you gathered in narrative form. When you showed it to the AIVD they quickly decided to censor it. You were eventually allowed to display the original book only once at the Tate Modern in 2009/2010, and only as a piece of visual art sealed securely behind glass. After that they confiscated it and redacted about 40 percent of the text. How did you feel after three years of work went into the void like that? Did the AIVD’s reaction to the work surprise you at the time?

J.M. - When I learned the AIVD was going to censor 40 percent of the text, I was devastated. I obtained an American lawyer who was convinced that I had a very good chance of fighting the agency’s decision, as I never signed a confidentiality agreement with it. After a long consideration I decided not to fight the censorship but to acquiesce to it and to every demand the agency made. I realized that the more boundaries and new rules it imposed upon me the more it exposed itself. And this had been my initial proposal: to find the human face of the secret service.

J.E. - I’m also really interested in the human and social side of your dealings with the AIVD. Do you think you were able to collect so much sensitive information from the AIVD’s employees because people there viewed you as harmless (i.e., because you were “just an artist”), or was there some other reason for their opening up to you?

J.M. - Being introduced to an institution like this as an artist was a first with the AIVD project. In my previous projects I never identified myself as an artist to the institution because I’d learned that doing so led to quick and inaccurate assumptions about my intentions. Calling myself a researcher (and arming myself with as much information as I could gather on the system) proved more ambiguous. I could present what I was doing or looking for rather than what I was identified as. But with the AIVD, I got “the job” because I was an artist. It was not that the agents told me things because I was an artist as much as it was the administration that disregarded me because of it. The agents and I met multiple times, got closer, while the administration turned a blind eye-until it read what I wrote and did not like it. I think the agents had many reasons for speaking to me: curiosity, wanting to use me to share their stories when they could not otherwise, wanting to see their institution through my eyes, needing to unburden themselves of their own histories-these were just some of the reasons they gave me. I also believe they spoke to me because I was genuinely interested in who they were, what they were doing in the agency, and what it was like to become anonymous. I think it is regrettable that we are in an age when a government institution like a secret service no longer assumes artists can have a real effect, beyond the decorative.

Failed States. Installation view at Honor Fraser, LA. 2012. Six Empty Shells, 2011 Wall installation 20 »x 30 ». Photo: Joshua White.

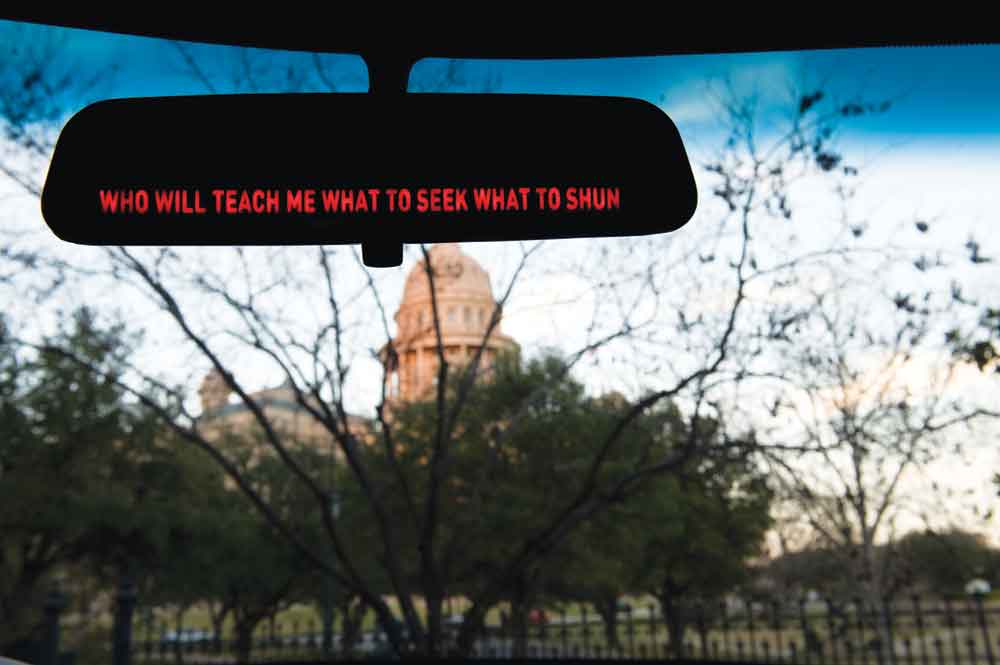

J.E. - On January 21, 2010 you were doing research in Austin, Texas, for a project about snipers, and you stumbled into an incident on the State Capitol steps in which a man named Fausto Cárdenas fired several shots into the air after unsuccessfully trying to speak with someone on the governor’s staff. The event led to Closet Drama (2011) and Failed States (2012), two mixed-media installations that presented the shooting as a strangely compelling expression of thwarted speech. What was it about that chance occurrence that led you to make it the basis for such a large body of new works?

J.M. - When I began the project I did not know how it would unfold or its eventual scale. It began with Fausto’s absurdist gesture of shooting up into the sky from the steps of the State Capitol. It was an irrevocable act; Fausto was condemned to await trial in jail (which took one and a half years), charged with making a terrorist act against a government institution. I’d witnessed the shooting by chance, but then chose to remain his witness by being present for all of his court appearances. Meanwhile, also in Austin, I was being trained by an Associated Press war reporter to embed with him in Afghanistan-a process that would teach me to be another kind of witness. As these two narratives unfolded simultaneously, I wrote the book Failed States to explore their connections, collected materials, and from this made many works and installations that took on the names Closet Drama and Failed States.

View of the exhibition “The Status of the Shooter,” 2012. Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris. Photo Didier Barroso.

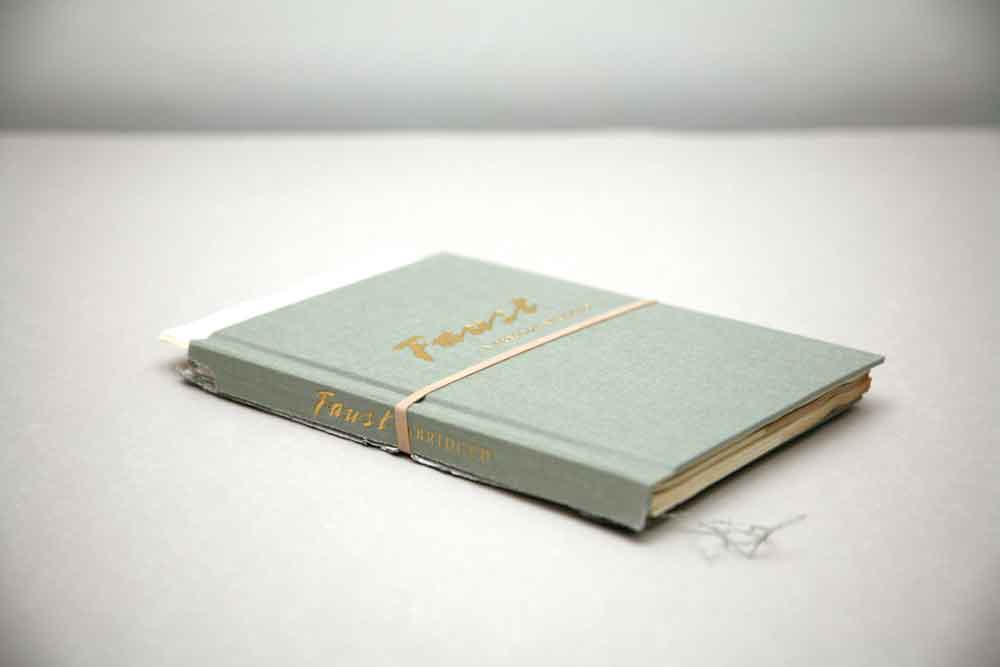

J.E. - You brought Goethe’s Faust in as a reference point in Closet Drama and Failed States What’s the connection between Faust and Fausto Cárdenas, and how did you end up using the play in the works that resulted?

J.M. - Initially, it was a hunch to read Faust due to the similarity of their names and the theatricality of Fausto’s act. Once I read the book, I became convinced that the associations were fruitful. A main connection is that both Faust and Fausto relinquished words in place of deeds, a choice that led to tragic consequences for both of them. The fact that Faust was originally conceived of as a closet drama (a play written for the mind rather than the stage), and the format of Goethe’s text helped me to think about and structure my installations. I treated the wall vinyl as stage directions and the prints, videos, objects, sound works and photos that I made as points along a narrative.

J.E. - More recently, you’ve worked on The Status of the Shooter (2012), based on an unrelated but eerily similar incident in which a student named Colton Tooley walked around the University of Texas at Austin firing an AK-47 into the air and ground, after which he committed suicide in the library. Can you describe some of the works in this project, and its relation to the prior Fausto Cárdenas works?

J.M. - The Colton Tooley shooting happened while I was following Fausto’s case. A professor of German literature at UT Austin that I’d been meeting with mentioned that he thought Tooley was “more Faust than my Fausto.” Wanting to explore what that could mean I filed an Open Records Request to the Austin Police Department to see what information the police had on the incident. Like Fausto, Tooley’s shooting had the feeling of a public performance. Tooley “performed” as a school shooter. Dressed in a black mask and trench coat and carrying an AK47, he walked through campus shooting into the air and ground, hurting no one. I received DVDs and a USB stick from the police. The DVDs held the dash cam surveillance footage from each cop car called to the library that Tooley had entered. I synced them and transcribed the audio. From the transcriptions I wrote Tooley A Tragedy, a libretto that literally dramatizes the action, and formatted it like Faust. I also reprinted Faust, but in an abridged form, cutting the play at the moment Faust is about to commit suicide in his personal library. The videos of the cars played on five screens, hung in relation to where each police vehicle parked outside the library. The chaos of the police search is juxtaposed with the silence of the books and the intimacy of the monologue from Faust, audible on headphones, of Faust considering his suicide.

J.E. - A lot of your work directly invokes stage plays and cinema. Among other things, you’ve juxtaposed Faust with police radio transcripts in The Status of the Shooter, staged dramatic readings of your novella Lincoln Ocean Victor Eddy (2007), treated the Liverpool CCTV surveillance zones as private movie sets and instructed the officers monitoring you in film theory, and placed stage directions on the walls of the Closet Drama installation at the UC Berkeley Art Museum to help viewers navigate the space. Why do you use such artificial, fiction-oriented means to present real-world events?

J.M. - I am not a journalist.

J.E. - When I watched some of the news footage of you taken during the Fausto Cárdenas trial, it occurred to me that a lot of viewers who didn’t know your resume probably took you for an obsessed fan of the defendant or some kind of true-crime junkie. That led me to wonder how much of your work has involved taking on a role, as opposed to just “being yourself.” Do you make that kind of distinction, and if so, do you ever find the two merging or alternating during a single project?

J.M. - In life people are always taking on roles. I do this in my life and in my work, but all of those roles are part of myself.

J.E. - Finally, I’ve heard that you’re working on a new project about corporate power. Is there anything you can tell us about that yet? It sounds like a kind of new arena for you, and I’d love to know what direction you’re thinking of taking your work after the recent pieces about Fausto Cárdenas and Colton Tooley.

J.M. - I am learning the differences between the powers of a corporation as opposed to those of a government institution. They are run by a different set of rules, and the former need not explain many of them. As for the direction I am taking this, that will become clear with time.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.