« Features

Société Réaliste: Dealing with Politics, History and Social Commitment

Behind the Paris-based collective Société Réaliste, founded in 2004, are Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy, a Franco-Hungarian duo whose work has been increasingly embraced by the international art community over the past few years with shows in, among other major cities, London, San Francisco, Istanbul and, this last spring, Paris, at the prestigious Jeu de Paume. Empire, State, Building, the title of this first major solo exhibition, exemplifies several aspects of Société Réaliste’s practice, among which appropriation, deconstruction (the use of commas to subvert the original meaning and jeopardize the symbolic function of the name) and the use of language to spread their ideas in publications and lectures, but also as a blueprint for understanding other systems of representation, such as designs, buildings, maps and films. Their central goal is perhaps to understand contemporary politics via aesthetics (old and new) and the other way around. By creating mostly objects (maps, charts, inventories, graphs, sculptures, designs), films and environments (interior designs, exhibition presentations), which result from the use of methodologies and systems of representation used in fields traditionally understood as alien to art, such as mathematics, ergonomics, engineering and economics (to only name a few), they show the ideological purpose they serve and the power of images to create specific identities. This may be surprising, considering their longtime interest in revolutionary forms and rhetoric, as the result is often visually cold and clinical, as if the works on show had been shaped with the precision of a razor-blade incision. And although Naudy and Gróf might look like kids from the suburbs, they word their incendiary talks as a seasoned surgeon would wield a scalpel. Their next major exhibition will be the second phase of their project and exhibition Empire, State, Building, hosted by the Ludwig Múzeum in Budapest from March 8 through April 22, 2012.

By Catherine Somzé

Catherine Somzé - This last spring you presented the project Empire, State, Building at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. What did it consist of?

Sociéte Réaliste - Empire, State, Building is an exhibition that we have constructed through an ensemble of artworks at the intertwining between architecture and language. Our main focus regards how the political and economic powers produce spaces and discourses, i.e. talking spaces, places where you can only listen to objects. In other terms, how the various sceneries in which we live-rooms, buildings, cities, nation-states, continental alliances-imply a set of political practices and ideological panoramas, denying the possibility of a difference. Ecomorphism is an appropriate term to describe this phenomenon, shaping inhabitants in the form of their habitat, just like in Orwell’s book 1984, where the walls’ transparency presumes people’s own transparence. Far from a kind of anthropological origin of human spaces, this mythological past when people created their environments in accordance to their needs and capacities, Naypyidaw or Dubai serve as models for our century, completely designed cities with no other inhabitants than pure functions, no other constructions than global lingua franca symbols, no other project than photo-shopped views of urban volumes. The same type of encompassing strategies-controlling through edges and spatial syntaxes-can be found in the confiscation and confinement of languages. To that extent, the title of this project expresses both our target and strategy: the name of a building standing for the construction itself, and punctuation revealing a core meaning by the suspension of common locutions. To give an example of this approach, we have presented in this exhibition our first full-length film, entitled The Fountainhead. Our film is an appropriation of the 1949 eponymous Hollywood movie, directed by King Vidor and written by Ayn Rand. The original film tells the story of a modernist architect from New York, fighting in the name of individualistic values against the decadence of his time, advocating modernist architecture for an all-capitalist world. It is a Cold War movie using the weapons of modern art. In our version, we have removed the sound and systematically erased all the human characters of this film. What remain are 111 minutes of pure architectural settings, a decorum telling by itself an ideological story, the one of a world enclosed in its own fantasmagoric representations, where even voids are scripting the text of domination.

Société Réaliste, The Fountainhead, 2010, video stills, black&white, silent, 1h50. © Société Réaliste. Photo: Société Réaliste.

C.S. - Since its foundation in 2004, Société Réaliste has initiated projects for which it has consecutively become a trend design agency for Transitioners, an art corporation for PONZI’s and more recently a research unit for the project Ministère de L’Architecture. So, what is Société Réaliste exactly? And what is its purpose?

S.R. - Société Réaliste is a cooperative working from a broad range of perspectives and fields, such as territorial ergonomics, experimental economy, political design or social engineering consulting, deploying experiments that find their formalization in the domain of art.

C.S. - What does ‘Réaliste’ stand for in the name you have chosen for your collective? Is it a criticism of the status quo? Or what could be seen as the current triumph of economic and political cynicism?

S.R. - The origin of our name, Société Réaliste, is an inversion in French of ’Réalisme Socialiste,’ Socialist Realism, the official artistic style of the former Communist world. Originally, our collaboration started under this name as a curatorial project, aiming to exhibit aesthetic correspondences between this artistic movement, totally under a ‘socialist’ ideological control and various forms of contemporary art, eternally reproducing the values and views of the dominant order under the form of artistic artifacts. Our project quickly moved from a curatorial orientation to the creation of a cooperative for art production. Realism is a term, within this scope, underlining our constant interest not in salon chitchat or bunker daydreaming, but in the forms under which political and economical reality is produced, and the possibility to divert and hijack those chains of production.

Société Réaliste, MA: Culture States, The future is the extension of the past by other means, 2009. Mural inscription with the Limes New Roman writing system. Installation view, Istanbul Biennial, 2009. © Société Réaliste. Photo: Nathalie Barki

C.S. - Do you consider your work as political activism?

S.R. - Art is a production activity occurring in political contexts. Therefore, the question would be: Which art can pretend not to be a political activity? At the very moment when it becomes public, when it addresses subjectivities, art inscribes itself in the political field. The shape of a garden, the rhythm of a film, the transposition of an artifact in a sculptural installation, any production of form comes from a political situation created by political beings and generates a new state for the same beings. Is there any production that is not involved in a political paradigm? This is why such a thing as political art does not exist as opposed to a non-political art. There are antagonisms in political directions taken by productions, variations in scales and effects, differences in methodologies, in referent histories, in formal genealogies, contradictions in frames of perceptions or figures to which are associated the viewer, but none of them are strictly outside of a political order. What can escape social determination, if society is the continuous consequence of political struggles? Producing a several-meters-high sculpture of a dog made out of flowers is a political act, because it implies the mindset in which such a form is relevant and meaningful, a world in which the privileged position is the one of a poodle in the Garden of Eden.

Société Réaliste, Transitioners: London View, 2009, digital prints. Installation view, Hold & Freight, London, 2009. © Société Réaliste. Photo: Société Réaliste.

C.S. - In the face of the current crisis of ideologies and widespread skepticism towards protest as a valid strategy for change, do you think political activism can go further than being a commentary?

S.R. - The only concrete lesson we can extract from historical knowledge is precisely the unpredictability of history. Which external professional analyst could have predicted in December 2010 that civil societies of so many Arab countries would get rid of their dictatorial governments through massive protest? There is no political evangelism, no perfect world to build, no ‘good news’ to spread, no Bible for revolutionary politics. There are situations of conflict, sides to take, actions to lead, knowledge to advance, criticism to formulate, forms to shape, mantras to deconstruct. Protest is neither invalid nor the only way. Every single possibility to erode the dominant order must be taken. The ruling class of market economy has taken the ‘end-of-ideologies’ or ‘crisis-of-ideologies’ as a key concept of its renewed ideology. On the contrary, the liberal governments of the First World have never been as ideological as now, most probably because their axioms are sinking from all sides: Market-driven decisions are socially totally irresponsible, capitalism and democracy have definitively no links, the only realized internationalism is the globalization of oligarchy. Social orders are suicidal. It is our global duty to help them die. Euthanasia through all media, unite!

C.S. - And what do you think about artists such as Allora and Calzadilla and Thomas Hirschhorn, among many others, who started making art with a political agenda and then abandoned their initial quest in order to fit the demands of art institutions and the art market?

S.R. - We do not think about them. We do not know what is or was their agendas. We do not consider their quests. Artists are not of interest. Artworks are. And if it has been possible in the past to sell as artworks for institutions and markets dadaist busts, meter squares of void or canned shits, why would it be different today? Isn’t it unbelievable in the 21st century that no art collector has bought for the ornamentation of his/her private foundation garden the column of tanks from Tiananmen Square?

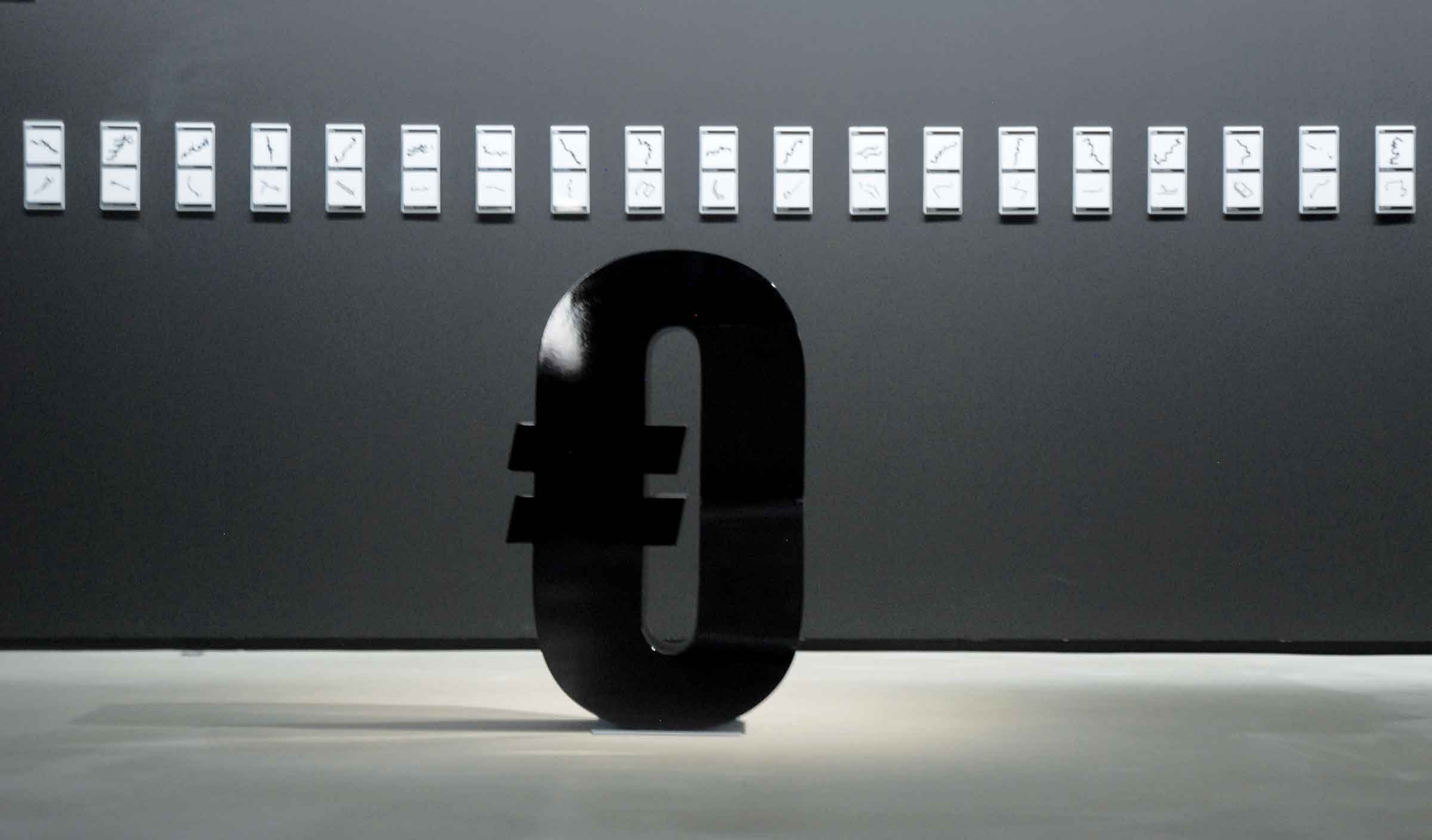

Société Réaliste, Empire, State, Building. Exhibition view, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2011. (Zero Euro, varnished sculpture in forex, 2011; Limes New Roman, enamel plates, 2010.) © Société Réaliste. Photo: Jeu de Paume, Arno Gisinger.

C.S. - At what point does an artist betray his or her initial political agenda and become an opportunist?

S.R. - Isn’t it already opportunistic to be an artist?

C.S. - You are currently developing a second stage of ‘Empire, State, Building’ that will be presented from March 8 at Ludwig Múzeum in Budapest. How does it relate to the exhibition at the Jeu de Paume in Paris?

S.R. - The exhibition that we are preparing for Ludwig Múzeum will be a reformulation as well as an extension of the one we did at Jeu de Paume. In Paris, the scenography was influenced by the wunderkammer effect, artworks were on display on several levels of the walls, we used the space almost unchanged, linear and continuous. In Budapest, due to the size of the space on the one hand and to our will to displace our focus points, the exhibition will be thematized and organized following a topography. Most of the rooms will be broken by walls, blocked, following the repetition of a key form that will link our work on scales of perception to our ongoing research on utopian architectural patterns. The attempt to produce linkages between the writing of architecture and the architecture of writing will be treated in the exhibition space itself. In addition to several new works under the form of light boxes, sculptures, installations, inscriptions or typographic proposals, we will present at the Ludwig a new film, which will be a counterpoint to The Fountainhead. When The Fountainhead was interrogating the architectural narrative of a film, this new one will try to put the production of cinematic images at the timescale of a human life.