« Reviews

Street Art, Street Life

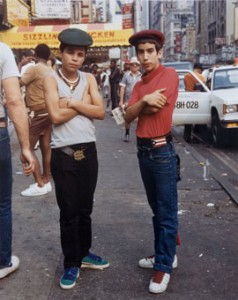

Jamel Shabazz. Untitled, 1981. C-print, 20” x 16” (50.8 x 40.6 cm). Courtesy Bronx Museum of the Arts; Gift of the artist and Kravets/Wehby Gallery, New York, 2005.1

Bronx Museum of Art - New York

September 14, 2008 - January 25, 2009

By Ernesto Menéndez-Conde

Since Baudelaire’s poetry -in poems such as A une passante- the streets of modern cities have been a recurrent subject in both literature and visual arts. With the arrival of avant-garde movements, the streets became a privileged space for trying experiments heading towards the socialization of art. The attempt of integrating art and life, initiated by Dadaists, Futurists, and Surrealists, was increasingly developed from the midfifties onwards. Many artists challenged traditional art institutions (like galleries or museums) and opened art to unconventional spaces.

Street Art, Street Life, the last show at the Bronx Museum of Art, conceived by the guest curator Lydia Lee, renders a summarized view of the entanglement between art, life and the streets of contemporary cities. The show includes some of the most controversial artistic experiments of the last five decades. However, it seems near to impossible to offer a complete overview of the countless practices made in Contemporary art. For instance, you might notice the absence of some public art, like Felix González-Torres’ billboards, Christo’s interventions in architectural landmarks, Robert Barry’s hidden marks in sidewalks, graffiti and Chicano murals, among many other relevant artistic projects. But curator Lydia Lee succeeds in showing the streets as a place for artistic intervention, representations of outsiders and sexual or ethnic minorities. I would say that her main approach is seeing art in the streets as a way of challenging dominant discourse. In that sense in Street Art, Street Life, there prevails a political dimension, which is related to a view from subalternity.

There are two main topics in the show. The first one is the view of the streets as a space of surveillance, in which there is a loss of privacy. In Yoko Ono’s video installation entitled Rape, two cameramen follow a foreign woman. At the beginning she feels flattered at being interviewed, but at some point the filming turns into a kind of harassment, which makes her feel threatened. The French artist, Sophie Calle, shows documents provided by a detective who was hired to watch her. In Lee Friedlander’s picture, the shadow of a man is projected over the back of a woman, who is passing by. Also Following Pieces, by Vito Acconci, consisted in following the steps of unknown pedestrians. The artist participates in and imitates, in a playful, ironic way, the idea of surveillance and paranoia, which is a hidden means of social control in contemporary society.

A second subject matter of the show is the representation of ethnic and sexual minorities: Latinos, Afro-Americans, views from African and Asian artists. Tehching Hsieh spent a whole year (from September 1981 until September 1982) living outdoors. His artistic project consisted in not staying indoors during this period of time. It was a way of integrating art into life, or rather transforming everyday life into artistic practice. Living on the streets is also a way of facing the experience of homelessness. Adrian Piper disguised herself as a black male character who approached white women in a provocative way. The photographer, Amy Arbus, took a picture of a woman wearing a fur bikini. During the conservative Reagan years -Fur Bikini was taken in 1987- Arbus used her model as a way of promoting freedom. Jamel Shabazz shows a series of pictures focused on Latino teenagers and Afro-Americans members of poor communities portrayed with a certain pride of having a cultural identity. The Nigerian-born artist, Fatimah Tuggar, makes photomontages combining images of New York with African landscapes. Tuggar offers subjective visions derived from the clash between the most sophisticated world and traditional societies.

Street Art, Street Life includes forty artists and a wide variety of media: videos, photographs, written documents, collages, posters, drawings and even a painting made by Martin Wong. The show could be seen as an eclectic revival of the sixties and early seventies, in which there is a rebellion against both art institutions and structures of power.

Ernesto Menéndez-Conde is finishing a Ph.D. in Romance Languages at Duke University. He has published in magazines in Havana, Spain, and New York. He has also collaborated with Marlborough Gallery and Sotheby’s in New York.

Filed Under: Reviews