« Features

Teresa Margolles: 21 Scores Settled / Malverde’s Jewelry

By Lourdes Morales

“ Grant me health, Lord; grant me rest, grant me well-being and I will be blessed “

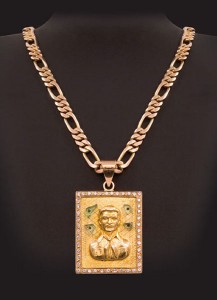

One of the pieces of jewelry in the series, Ajuste de Cuentas 15 (titled by the artist, “Score Settling 15“), is comprised of a rectangular pendant that shows in high relief the bust of the patron saint of drug dealers, Jesús Malverde. Four small shards of green glass - two on each side - are placed above the shoulders. It would appear that the jeweler had in mind the halo or the glow emanating from Catholic divine representations. The edge of the piece is encrusted with gems. The gleaming creation hangs from a thick gold chain. The protector of outlaws, Malverde, started out by robbing rich landowners who traveled through the Culiacán Valley in the State of Sinaloa. The incorrigible bandit died in 1909 at the hands of General Cañedo’s henchmen - so the story goes. Today three chapels bear his name: one in Cali (Colombia), another in Sinaloa (Mexico) and, of course, another in Los Angeles (United States), tracing “the cocaine route” - as they say.

Ajuste de Cuentas 15 also corresponds - according to the note that accompanies the piece - to a 34-year old man killed “…while riding in his car on the Culiacán-Eldorado highway… ” [1] He was a Municipal Police officer and “… died as a result of multiple wounds in the head, thorax and abdomen.” [2] They “… recovered 30 shells casings from AK47 assault rifles and AR15 rifles, as well as a 45 mm caliber gun.” [3]

There are a total of 21 “Score Settlings,” 21 pieces of jewelry - rings, bracelets, bangles, pendants, earrings, etc. - that Teresa Margolles had made at Joyería Anne in the Rafael Buelna market, a place situated in downtown Culiacán, where small establishments supply all sorts of accessories to low-income people. This location abets and is a venue for drug trafficking.

In an exercise of displacement, far from the noisy streets with its masses, the artist presented this series in November 2008 at the Galería Salvador Díaz in Madrid and at Art Positions - Art Basel Miami Beach in December of the same year. The pieces of jewelry were exhibited in a solemn, dark, even elegant, atmosphere; each piece occupied a dramatically lit black pedestal showcase. On this occasion, the artist’s intervention consisted of generating a collection of glass fragments that she took from crime scenes and later used to replace precious stones in pieces of jewelry. Thus, Malverde’s “glow” is, curiously, ill gotten. It is the result of a tragedy that Mexican politicians have called: “The fight against organized crime.” [4]

A native of Sinaloa, a state in northern Mexico traditionally characterized as being a drug-trafficking zone, Margolles addresses in her oeuvre the serious issue of violence. Her practice has garnered international attention because it combines her two professions: medical examiner and artist. Works of art are developed in the processing of cadaverous materials, generating installations, sculptures and artistic interventions.

Her concern, however, lies in respectfully shedding light on the unique casualty, the individual account, which has been lost in the midst of social turmoil - the absolute, final, unique and unrepeatable fate, which we all seal the moment we are born. The sphere of ethics and politics in this artist’s approach refers to the realm of the individual, to the solemn ritual he performs and to the identification of the sacrifice, where the uniqueness of the victim propels the machinery. Margolles redefines the victim’s political function as action that directs society as a whole.

The new Mexican folklore?

Regional physiognomy changes in the same way that wrinkles record the state of mind on the skin or sometimes mirror pathos or act as narrators of personal history. Likewise, social eras incorporate individual facial expressions and little by little imprint a geographic expression.

As if it were a countenance, folklore is an exquisite manifestation of communal expression. It is a gesture par excellence that reveals the tone of a collective history -even when “the common” in community finds itself splintered or embroiled in the breakdown of its own constitution. As Jean-Luc Nancy would say, the community is a praxis not a tangible, and in the flow of the intensity of being alike we coexist molding the shared horizon. Inseparable from that which is public, from the open spaces that shape us - in setting foot on its streets, in recognizing the familiar faces of our neighborhoods - we form ideas about each other, we communicate with each other and we call each other by name. Together we produce a quotidian echo that, in turn, subverts the realm of order. It is a movement that in its folds reveals new evidence of uses and customs.

The word folklore is comprised of folk, which signifies people and lore, which refers to the science or the knowledge of the people. One could then pose the question: What does this popular knowledge narrate in a world of global mafias, which become diluted in the daily life of individual places?

Ernesto Diezmartínez dedicates part of his article on Teresa Margolles’ piece to the figure of the buchón, designating him as a flunky, a henchman, a low-level drug trafficker, who dresses in an extravagant and vulgar manner. According to Diezmartínez, today’s buchón also has imitators who yearn for the power of the drug trafficker, configuring their desires in “…outward displays: brand-name shirts, gold slave bracelets with encrusted diamonds and … the leasing of impressive Hummer limousines.” [5]

Margolles introduces her oeuvre at a time of social redefinition: violence as a cultural phenomenon. That is to say, violence as the expression of the foundation of cultural industry and as the reason for the development of a specialized economy; as the expression of the production-consumption relationship based solely on the bloody dichotomy of power - pursuers and the pursued, victims and perpetrators, cops and robbers; violence as a mechanism of expansion for small economies, upheld by all of the publicity tools of a well-established market. We need only recall the uproar caused by Forbes magazine when they included in their list of millionaires, Chapo Guzmán, one of the leaders of the largest drug cartel in Mexico.

This is how it sounds on the radio in a pickup truck in the northern part of the country: “Yo con los business no me freakeo tengo mi escuadra y si quieren fuego yo les contesto, pues no la traigo pa’ apantallar.” (Narcs don’t freak me out; I got my posse. If they want war, bring it on. I ain’t frontin’.) Los Sonoreños sing their song El Buchón.

A new tradition appears to be taking shelter within the limits of localities/communities that harbor ways of dressing, speaking, types of music, jewelry design…, all of the components that anthropologists have identified as defining the concept of culture. In his book The Ruin of Kasch, the Italian thinker Roberto Calasso mentions:

“If industry is a sacrificial workshop, the prestigious value of the New means that a certain object is the fragrant remains of sacrifice. [...] The gods devour the precious prototype; they leave man the endless copies. For this reason industry is based on reproducibility. The star, however, is a Catasterism, ascended into the heavens after having been devoured by the gods.” [6]

The figure of Malverde thus emerges mythically transformed, having atoned for his sins as an outlaw and villain. Risen to the constellations, to the heavens that only saints occupied, in a world of dissipated divinity, Malverde - The Star - offers himself up as a victim, as a sacrifice; surrendering his dark life for the sake of continuity, for the stellar movement that gives rise to the New, the New Culture, the New Folklore.

Pieces of jewelry, upon being modified by the artist, reveal the complicity inscribed in the sacrificial act - a pact sealed between the victim who offers himself up and a society that contemplates the media halo (Forbes) or the esoteric niche (Saint Malverde). It is a formula that perpetuates excessive consumption, the necessary waste that builds a global society. As Calasso mentions, industry, far from nullifying tradition, deals with archetypes; it buys and sells, at the same time that it maintains a necessary esotericism. Thus, Margolles’ great strategy in this oeuvre lies in camouflaging it as the residual act of violence, as an operation in the production-consumption cycle. Her series warns of the foolish oblivion to which we relegate exchanges that, like it or not, whether we know it or not, form the basis of cultural industry.

Teresa Margolles has been selected as the official artist who will represent Mexico at the 53rd Venice Biennial (June 7 - November 22, 2009). The art critic, Cuauhtémoc Medina, will be in charge of this curatorial project entitled: “¿De qué otra cosa podríamos hablar?” (What Else Could We Talk About?).

Notes

1- Margolles Teresa, “Score Settling 15,” Text that accompanies the piece of jewelry

2- Ibid

3- Ibid

4- Ernesto Diezmartínez. “Brillantes” In: Catalog 21. Galería Salvador Díaz, Madrid, 2008, pp. 45-52

5- Op. cit.

6- Calasso Roberto, The Ruin of Kacsh, Anagrama, Barcelona, 2000, p. 142

Lourdes Morales: Art historian, freelance writer and independent curator. Author of Master Thesis De la Oscuridad a la metonimia: un ensayo sobre SEMEFO y Teresa Margolles (From Obscurity to Metonymy: An essay on SEMEFO and Teresa Margolles). Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, UNAM, Mexico City, 2006. She is part of LC060 (Laboratorio Curatorial 060), an experimental collective interested in questioning the ideas that define contemporary cultural practices. Morales is finishing her PhD in Art History and Critical Theory (UNAM, Mexico City).