« Features

The Aesthetics of Cellphone-Made Films

By Caridad Botella

THE HAND WITH A LENS

The first films shot with mobile phones appeared between 2005 and 2006, among them the feature film SMS Sugar Man1 (2005-2006) by South African director Aryan Kaganof, which is regarded as a revolutionary, alternative way of making films with the limitations imposed by a mobile phone. Another pioneering film considered among the first ones is New Love Meetings (2006) by Marcello Mencarini and Barbara Seghezzi. According to a June 14, 2006, report by The Guardian about New Love Meetings: “The limitations of filming with a mobile phone-having to film at close range, weak sound capture and the slightly shaky picture-turned out to be advantages for them, leading people to open up a little more easily.”2 Mobile devices “insert” a lens in everybody’s hand: Capturing reality at any moment and place of the day has never been so accessible. During the past several years, films made with mobile phones have received the attention of not only the press but also film and media scholars. But in order to better understand them, it is important to define the aesthetic and stylistic characteristics of cellphone-made films, which has led to new ways to categorize and define them.

The mobile, portable aspect of the filming device is of utter importance when it comes to understanding cellphone-made films. Roger Odin, one of the first to try to categorize this new genre, makes a distinction between cinema uno3, the photographic cinema of the “trace,” which is “made to be seen in a room by a spectator invited to adopt a specific discipline of the eye,” and cinema due, or digital cinema, which is consumed in many different kinds of “dispositiefs“-”which are often inscribed within the communication of the multimedia, of the game…or of the physical effect…rather than with that of the narrative”(Odin 2009). Within cinema due, the camera phone stands out as a different element: the camera as a prosthetic eye in the hand, an extension of the body that makes mobile-made films different, as the camera slowly integrates with the human body (Odin 2009). This distinction deserves a special consideration since cinema due is too vast, so Odin comes up with a subcategory, p-cinema: “the part of cinema due which is made with a mobile phone.”4 Odin’s category is based on the prosthetic aspect of the mobile phone, which translates into a shooting style. And so with Odin a new category is born, which opens the doors to new interpretations and analyses of an emerging cinema practice.

MOBILE AESTHETICS

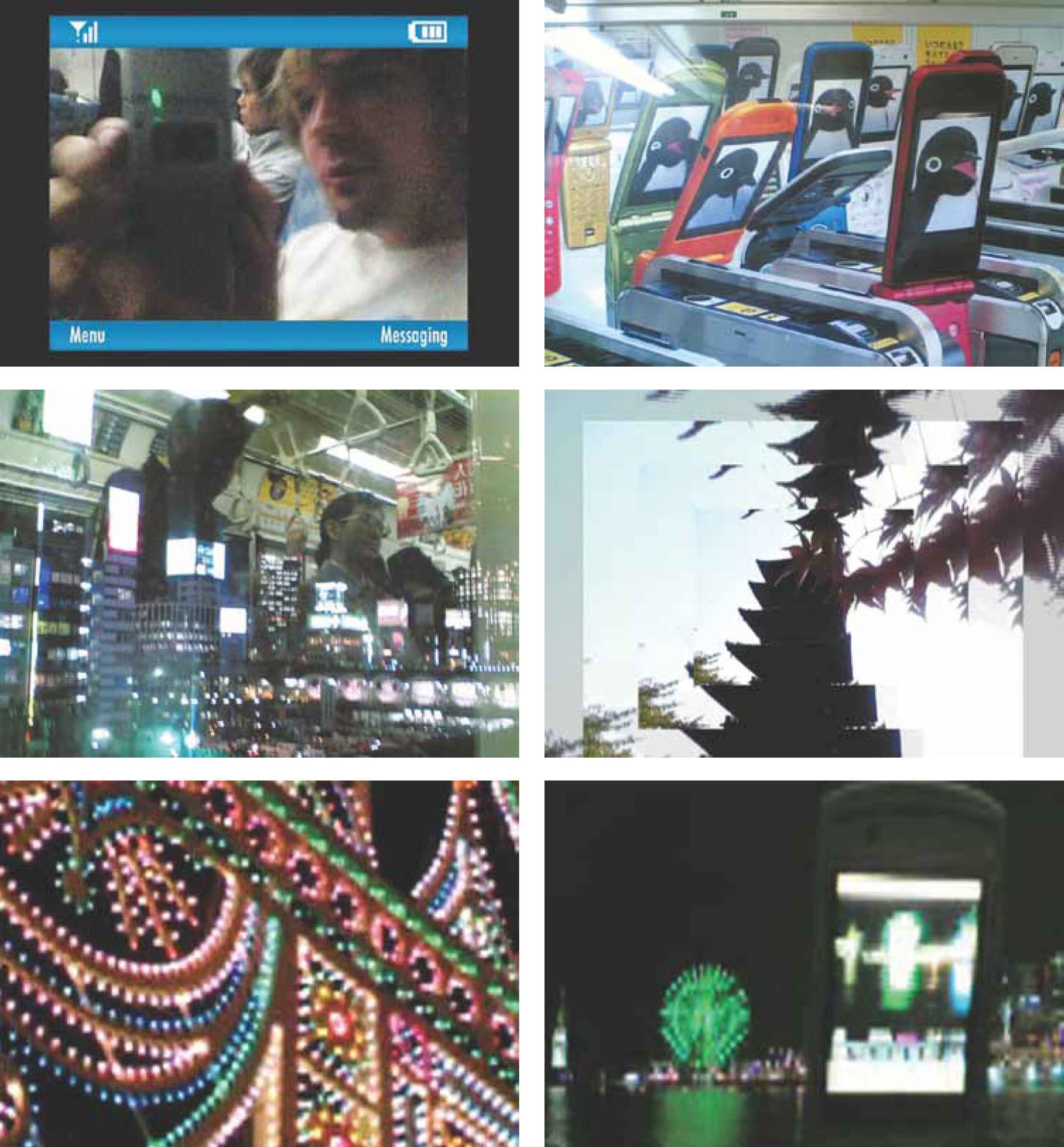

Pixelated images due to low-resolution cameras-so iconic in the beginning-have become a conscious choice, as high definition (HD) is now the new standard. In the beginning, low resolution and the consequent pixelation of the image gave impulse to a low-res aesthetic. This effect is embraced by makers and considered as an asset in the end result. But low-res was soon superseded by better quality cameras; for films made in the last few years (2010 and later), low resolution is an option as, for instance, the mobile device iPhone4 (and other models) records in HD, in which there is hardly any trace of pixels.5 This phenomenon raises important questions about the quality of the image as a characteristic of cellphone-made films. Is there such a thing as mobile aesthetics beyond the celebrated shortcomings? Is the tool itself a unique asset when it comes to capturing reality, regardless of the number of pixels? In their short lifespan, what seems to be true is that the very concept of cellphone film aesthetics is quite “mobile” itself as devices keep developing and changing very rapidly.

Media artists and scholars Camille Baker, Max Schleser and Kasia Molga support the idea of image pixelation as a defining characteristic in mobile aesthetics, but they also consider other aspects that derive from the accessible character of the cellphone. In their common article “Aesthetics of Mobile Media Art,” they argue for the “existence of aesthetics unique to the mobile media,” looking at the “mobile media specific qualities of immediacy and intimacy” (Baker, Schleser and Molga 101). They consider mobile phones to have brought new standards when it comes to aesthetics. Moreover, the German director and film scholar Max Schleser has introduced a new category derived form the use of cellphones: the “mobile-mentary.” “The category can be defined through the characteristics of an original aesthetic signified by pixelated video images,” Schleser says. “Thus, it is the mobile phone’s limitations that are the defining pattern for the establishment of this new format” (Baker et al. 102). His statement seems to define a timely image prior to when cameras began to become more complex.

Perhaps it is necessary to look beyond the question of the image quality to find unique traits of cellphone-made films. Schleser refers to the new mobile aesthetics as “Keitai“ aesthetics. In Japanese, “kaitai” means “hand-carry, small and portable, carry, carrying something, form-shape or mobile phone” (Baker et al. 102). Given this definition of Keitai, the concept of aesthetics derived from it goes beyond image quality into more philosophical aspects of the mobile phone use. Schleser assigns three levels of Keitai aesthetics: to begin with, the visual level, which is characterized by the pixelation of the image. Even though he doesn’t mention HD, he marks a certain periodization: “In mobile phone filmmaking, the period between 2005 and 2008 is characterized by advancement from the 3GP mobile phone video file format to the mpg4 compression format.” (Baker et al. 102) Schleser’s own work is a good example of this as it contains both formats in one video: Max with a Keitai (2008)6, produced with two cell phones during 56 days in 2006 (Baker et al. 102-103).

Moreover, Odin suggests certain “tendencies” that can add further meaning and information about the pixelation aspect within the visual level of Keitai aesthetics: contingent elements that depend on the pixelation of the image-constraints “which can be quite productive in terms of creativity” (Odin 367). Two of these tendencies are: pictorialism, in which we find a direct reference to painting, mostly due to the resemblance between the brush stroke and the pixel, but also because of the correspondence between the vertical format of the painting and the mobile screen. An example is the short film La Perle7 (Marguerite Lantz, 2006); in this short film, a young girl uses a cellphone as a mirror to dress and compose herself as the lady in Johannes Vermeer’s painting Girl with a Pearl Earring. Odin argues this effect works as long as the pixel is visible to make reference to the brushstroke.8 A second tendency is diegesis of the pixel effect, which refers to the importance of the pixel within the narrative of the story. Dutch filmmaker Cyrus Frisch is an example of this, as he shot his film Why Didn‘t Anybody Tell Me It Would Become This Bad in Afghanistan (2007) with a low-resolution mobile phone (he purposefully bought the lowest resolution possible) in order to stress the alienation the protagonist feels when he looks at the world from his balcony; in this case the narrative becomes stronger by the use of a pixelated image. “I started to film teenage immigrants,” he says. “Because of the limitations of the medium, you can’t hear them so well. It seemed a threatening and scary experience. [...] It became a perfect metaphor for what was going on with society at that time. People are scared for things they can’t name. [...] I saw this view of the world through the images recorded with the phone” (Botella 25-27).

Cyrus Frisch, Why Didn't anybody tell me it would get this bad in Afghanistan, 2009, cellphone-made film, 70 min. Courtesy of the artist.

INTIMATE, IMMEDIATE AND EVERYDAY AESTHETICS

What happens to the first level of Keitai once the image has improved? The attention shifts from visual image quality to a deeper understanding of the identity of the image: intimacy, immediacy and everyday images that are available to us due to the portable, daily use of the device become now the elements to define mobile aesthetics. As Schleser writes, “As a portable and personal medium that one has always in reach every day and night, the notion of the everyday remains prominent.”9 The attention shifts from low resolution to the camera phone as a tool that captures our everyday reality. An example of this is the 2011 short film Splitscreen: A Love Story by James W. Griffiths.10

The second aesthetic level is related to the effect cellphones have on body language and how this is assimilated in the viewing and screening process using cellphones (Baker et al. 103). This brings together new media aesthetics with the theory of embodiment: The experience of the world (as maker and audience) is not only limited to our vision but involves the whole body. A change of paradigm is suggested, from a “dominant ‘ocularcentric’ aesthetic to a ‘haptic’ aesthetic rooted on the embodied affectivity.” (Baker et al. 104).11 This has changed media experiences incorporating “the capacity of the body to experience itself “as more than itself,” and thus to deploy its sensorimotor power to create the unpredictable, the experimental, the new.12 (Baker et al. 104) An example of the cellphone as locative media and its relation to haptic is Fear Thy Not (Sophie Sherman, 2010). The filmmaker’s hand remains always in close-up and guides us through the space in which she finds herself. By this means she is able to communicate her experience of a particular location.13

The third aesthetic level dwells in the previous one; it is “connected to qualities of a state of ‘in-betweenness’ that refers here to “how mobile media operate in between photography, video and the Internet, while simultaneously establishing new links. The mobile phone merges communication and lens-based media.”14 This translates into a reflection about the private and multimedia role the cellphone has assumed in recent years, not only as an object to take pictures or make movies but also as a tool for verbal communication. We can find a trace of these multimedia-related levels in Odin’s categories and examples. For instance, he suggests the tendency of the telephone and its different uses.15 The cellphone is reflected upon in its GPS function in GPS Yourself16 (Rémi Boulnois 2008). In this movie in which a man uses his own telephone in order to locate himself via satellite, we can find a metaphor for the second level of Keitai aesthetics that relates to the mobile device as locative media (Odin 371).17 Both physical presence and interaction are embedded in Schleser’s ideas.

A sense of what Keitai aesthetic levels two and three really entail has become more sophisticated and complex as a result of transmedia projects that embrace the multimedia aspect of cellphones and the possibilities created by projects specific to mobile apps. For instance, this year’s (2012) Festival Caméras Mobiles, directed by Benoît Labourdette, includes such projects in its program, broadening the idea of what cinema is becoming due to the complex nature of cellphone cinema and rapidly evolving technology. An example is “Walking The Edit“,18 a system that explains how “to walk a movie” so that one can record a walk, which can then be translated into a movie though an iPhone app. This application “geo-localizes” the walk, converting it into a story drawn from all the augmented information around us.

MOBILE CONCLUSION

Defining mobile-made films’ aesthetics is a changing enterprise. It becomes clear that it involves different levels of and approaches to reality: On the one hand we consider how the cellphone filters the world through different types of lenses (low-res, HD), while on the other how we experience our environment through a mobile device-and even further what kind of communication and information we have access to through the device. It is the combination of these levels and approaches that points towards a unique way of filming. The challenge of remaining distinctive lies in the development of a unique image language and identity and points towards the creation of “personal and autobiographical statements.”19 Therefore, we find aesthetics that derive from the portability of the mobile device, such as the immediacy, intimacy and everyday that a cellphone camera can deliver and that become a unique aspect of mobile filmmaking.

This brings us back to Odin’s subcategory of p-cinema: The size and mobility of the device stimulate a certain use of the camera phone that translates into what might be a new shooting aesthetics. Moreover, Baker et al. suggest20 that portability facilitates the movement of the camera, which creates a gesture and blurring effect. On the other hand, portability and size encourage intimacy, which translates into personal images and a predilection for close-ups. Finally, the portability factor brings the world closer to the user through the lens and mobile screen, which becomes a “window on the world” (Baker et al. 108-109). Thus, regardless of the image quality, Odin’s p-cinema seems open to convey and embrace the three aesthetics levels mentioned. All important and enduring aspects of cellphone-made films seem to derive from the accessible and portable characteristics of the filming device: It ultimately makes reality available to record and therefore possible to construct personal, everyday narratives.

NOTES

1. To be seen online: <www.smssugarman.com>

2. “Full-length film shot on phone,“ published on The Guardian, 14 June 2006, <http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2006/jun/14/news2>

3. Odin constructs his argument based on Franceso Casetti’s work L‘occhio del Novecento, Milano: Bompiani, 2005.

4. Translated from Odin’s article in French: “telephone portable”, therefore p-cinema.

5. After I begun this research, iPhone and iPad video effects became available, though which we can add various nostalgic effect (8mm, 16mm, 1910’s among other) opening a different research path regarding current mobile device video aesthetics.

6. To be seen on: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1jc2iLI5Mx0>

7. To be seen on: <http://www.margueritelantz.com/laperle.htm>

8. Referring again to artist Raul Marroquin’s work-he often mentions the fact that regarding pixelation we’re dealing with a new form of Pointillism.

9. Ib. id.

10. To be seen on: <http://vimeo.com/25451551>

11. Reference to an original text as Hansen 2004: 11.

12. My Italics

13. See, Max Schleser <http://culturevisuelle.org/blog/6410>

14. As an example of “new link” the authors mention the semacode, “a mobile barcode technology which allows mobile phone users to connect to online environments though taking a picture of the specific mobile bar code. (Baker et al. 105)

15. Originally two tendencies that I have contracted into one.

16. To be seen on: <http://www.lexpress.fr/culture/cinema/la-video-dans-la-poche_510980.html>

17. Odin makes brief reference to this concept through a footnote, in which he mentions Casetti’s suggestion to consider the mobile phone from this perspective: footnote no. 24

18. See, <http://walking-the-edit.net/>. Other transmedia projects in the festival: <www.crowdvoice.org>, <ww.txtualhealing.com>, <www.codebarre.tv>

19. Max Schleser blog post on http://culturevisuelle.org/blog/6410

20. The context of these observations is the project MindTouch, Camille Baker’s Ph.D. project which is an “effort to connect people remotely through biofeedback sensors and the mobile phone, allowing them to re-engage with each other affectively and expressively in new creative, non-verbal/non-textual ways with the word through mobile video performance event. (Baker et al. 121)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Amaducci, Alessandro. “L’occhio nella mano.” In: (ed.) Maurizio Ambrosino, Giovanna Maina, Elena Marcheschi, Il Film in Tasca. Videofonino, cinema, e televisione. Ghezzano: Felici Editore Srl, 2009, pp. 143-155.

- Ambrosini, Maurizio. “Visiono digitabili. Il videofonino come schermo.” In: (ed.) Maurizio Ambrosino, Giovanna Maina, Elena Marcheschi, Il Film in Tasca. Videofonino, cinema, e televisione. Ghezzano: Felici Editore Srl, 2009, pp. 13-29.

- Baker, Camille; Max Schleser; Molga, Kasia. “Aesthetics of Mobile Media.“ In: Journal of Media Practice. Vol. 10, Nrs. 2&3, 2009, pp. 101-122.

- Botella, Caridad. “An Interview with Dutch filmmaker Cyrus Frisch.” In: Off Beat Cinema. August-July 2011. <http://issuu.com/offbeatcinema/docs/summer2011>

- Full-length film shot on phone <http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2006/jun/14/news2>

- Kevin Fitchard. Mobile Cinema Debuts, 2007.

<http://connectedplanetonline.com/wireless/marketing/telecom_mobile_cinema_debuts/>

- Hart, Jeremy. Video: Pocket Film Festival, 2009. <http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2009-04/15/pocket-film-festival-video>

- Marcheschi, Elena. “Videophone: A New Caméra Stylo?” In: (ed.) Casetti, Francesco, Jane Gaines, Valentina Re. Dall‘inizio, alla fine. In the very beginning and the very end. Film Theory in Perspective. Udine: Film Form, 2009, pp. 389-394.

- Marcheschi, Elena. “Realizzare sguardi utopici. Il videofonino come mezzo di represa.” In: (ed.) Maurizio Ambrosino, Giovanna Maina, Elena Marcheschi, Il Film in Tasca. Videofonino, cinema, e televisione. Ghezzano: Felici Editore Srl, 2009, pp. 29-34.

- Odin, Roger. “Question Poseé `a la thórie du cinema par les films tournés sur telephone portable.” In: (ed.) Francesco Cassetti, Jane Gaines, Valentina Re. Dall‘inizio, alla fine. In the very beginning and the very end. Film Theory in Perspective. Udine: Film Form, 2009.

- Schneider, Alexandra. “A new type of cinema? Some preliminary observations about phone films.” In: bianco e nero no 568, 2010, pp 75-83.

FILMOGRAPHY

- Boulnois, Rémi, GPS Yourself. France, 45 sec., 2008.

- Delbono, Pippo. La Paura. Italy, 69 min., 2009.

- Fitoussi, Jean Charles. Nocturne pour le roi de Rome. France, 80 min., 2005.

- Frisch, Cyrus. Why Didn‘t Anybody Tell Me It Would Get This Bad in Afghanistan. NL, 70 min., 2009.

- Kaganof, Aryan. SMS Sugar Man. SA, 81 min., 2005-2006.

- Labourdette, Benoît. Triton. France, 62.02 min., 2007.

- Lantz, Marguerite. La Perle. France, 4 min., 2006.

- Marceau, Dauphine. Totem. France, 4.51 min., 2008.

- Marroquin, Raul. Pisa Asciano. NL, 4:13 min., 2007.

- Mencarini, Marcello and Barbara Seghezzi. New Love Meetings. Italy, 93 min., 2006.

- Moon, Vincent. Tourner en rond et se laisser consumer. France, 4 min., 2006.

- Schleser, Max, Max with a Keitai. UK, 5 min., 2006.

Caridad Botella is an art historian and independent art and film curator based in Bogotá, Colombia. From 2006 to 2011, she worked as director at Witzenhausen Gallery in Amsterdam and is now director of “Independiente,” the gallery’s curating project in Colombia. She is a frequent contributor to various publications in Europe and the U.S. and regularly lectures about cellphone filmmaking, new media curating, film appreciation and art history.

[...] “The Aesthetics of Cellphone-Made Films” by Caridad Botella http://artpulsemagazine.com/the-aesthetics-of-cellphone-made-films [...]