« Features

The Ethics of Encounter

Art’s bad boys are back. Examining the complex interfaces which have emerged between ethics, aesthetics, and politics in recent art practices, this article expands upon some of the themes raised by “The Ethics of Encounter,” an exhibition I curated at Stills Gallery, Edinburgh in Winter 2010/11. It included works by The Atlas Group, François Bucher, Renzo Martens, Dani Marti, Frederick Wiseman, and Artur Żmijewski.

By Kirsten Lloyd

Dani Marti’s homespun sex therapy sessions filmed and screened to a gallery audience; Artur Żmijewski coercing a Holocaust survivor into having his identification tattoo refreshed; François Bucher’s documentation of the fallout from a violent theatrical experiment during which the audience was taken hostage; Renzo Martens’ brutal exploitation and humiliation of poverty-stricken Congolese families and workers. These are just some samples of recent video documents in which ethical questions are positioned center-stage. Transgression is, of course, nothing new in the field of art; much avant-garde production was dedicated to the disruption of moral pieties, and the shock doctrine has held sway pretty much ever since. Yet with art’s latest re-emergence as a social practice, this enduring characteristic has taken on new dimensions, throwing up alternative interfaces between ethics, aesthetics, and politics.

Dani Marti, Bacon’s Dog, 2010, video still. All images are courtesy of the artists and Stills Gallery, Edinburg.

Bacon’s Dog (2010) is a visceral account of the first sexual experience of Peter Fay, a 65-year-old writer, curator, and art collector from Sydney, Australia. Working with Peter over a period of five months, the Glasgow-based artist Dani Marti introduced him to physical intimacy in exchange for the opportunity to film their encounters. In the associated excerpts taken from email dialogues between the two men, Peter is devastatingly honest about his situation, going into some detail about the harrowing impact of his childhood medical problems and the liberating effect of Marti’s project. In contrast, the video itself is almost abstract in approach, dwelling on close-up shots of pale, mottled skin, clasped hands, caressing fingers and inscrutable gasps to produce an oppressive eleven-minute vignette. A quick glance at his extensive oeuvre confirms that Marti is something of a master at eliciting this kind of confessional storytelling. His various informants lie naked in bed beside him, yet he remains a peripheral presence, silent to the extent that his own personality appears to have been hollowed out in order to arrive at a condition of pure responsiveness. His subjects expand into the gap he leaves, further exposing their desires and vulnerabilities as Marti pursues an almost vampiric desire to draw closed encounters into the public sphere.

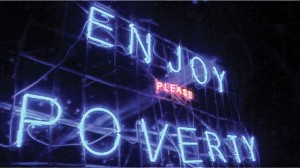

Renzo Martens’ feature length documentary Enjoy Poverty - Episode III (2009) records passages from the artist’s two-year journey across the Democratic Republic of the Congo. But in place of another conventional description of the misery which besets the lives of so many in this region, Martens employs brutal satire to render power structures visible. He performs an array of characters over the course of the film, subtly moving from colonizer to ethnographer, from entrepreneur to celebrity in an apparent attempt to embody the operations of global capital and the various roles and attitudes it unleashes. In one sequence, he invites a group of men who scrape a living photographing birthday parties and weddings to participate in a basic economics lesson, during which he persuades them that they should turn their attentions to the considerably more lucrative horrors of war: raped women, corpses, and starving children. The artist/entrepreneur then takes his students on field trips to hospitals and refugee camps, instructing them how to photograph a grieving mother, and the best angle from which to capture the distended belly of a severely malnourished child. Of course, it eventually becomes apparent that the men cannot access the networks through which to sell their images, and their hopes are cruelly dashed. The video’s defining scene documents a party held around a billboard-scale, flashing neon sign, which entreats his hosts to ‘Enjoy Poverty.’ Displaying a sociopathic knowingness, apparently devoid of empathy or remorse, Martens repeatedly denies his subjects either respect or agency; rather than simply represent or witness injustice, he provokes and performs it precisely for consumption by the viewer.

BIOPOLITICAL PRODUCTIONS

Ignoring for the moment the ethical valence of these works, Dani Marti and Renzo Martens share many of the same methodologies as scores of other artists who describe their practice as collaborative, participatory, or community-based: they stage relatively small-scale interventions, frame themselves and their production methodologies as part of the work, and focus on dialogic social relations. Boris Groys has argued that such practices reconceive the relationship between art and life in a completely new context ‘defined by the aspiration of today’s art to become life itself, not merely to depict life or to offer it art products’ (Groys 55). Leaping into the territories of biopolitical production, artists move away from the traditional tactics of mimesis and representation to instead stage experiments, shape situations, and otherwise direct social realities. The salient feature of this type of reconfigured artwork is that it can’t be distinguished from actuality; as the writer Stephen Wright explains, it is simultaneously whatever it is and an artistic proposition of the same thing (Wright). In other words, the performative frame of art operates on a “now you see me, now you don’t” basis, emerging from and dissolving into the social fabric of everyday life. When we watch these videos and see participants conversing, touching, becoming sexually aroused, and-in the case of Episode III-even dying, the significance of these observations is thrown into sharp relief.

Not surprisingly, then, after generations on the sidelines, issues commonly found in the realm of ethical critique now dominate the reception of biopolitical works. When artists’ labor bears a close resemblance to ethnographic mapping, investigative journalism, or even community work, can they be subjected to the same ethical codes and responsibilities as practitioners from other disciplines? Should we value artistic interventions which are productively ‘good’ or those which are transgressive, ‘bad,’ and yet ultimately revealing? Such questions rehash the age-old heteronomy vs. autonomy debates, giving rise to the two caricatures of contemporary practice: the ultra-ethical artist-as-social-worker and the unethical artist-as-sociopath. While one dedicates his practice to the amelioration of suffering and the strengthening of social bonds, the other, assuming the position of the outsider, prefers the challenge of disruptive shock tactics. Camps of followers have established themselves at either end of this polarity, shouting their differences across the pages of art magazines, journals, and catalogues. But in the drawing of this divide, a crucial point has been missed: whether artists are setting up low-cost housing initiatives for young, single mothers or harassing Holocaust survivors, eliciting an ethical response is often part-and-parcel of the work. Citing work at ethical flashpoints has now become so commonplace that a brief inventory of popular subject matter-prostitution, poverty, war, and human rights-tends to read like the contents page of an applied ethics textbook. Add to that the pervasive fascination with themes from ethical discourse-justice, rights, responsibility, and power-and ethics starts to find its place at the beating heart of art’s social turn.

ALWAYS TURNING

The social turn, the ethical turn, and the documentary turn. The apparently insatiable demand for the art document in recent years can, in part at least, be put down to its role in reclaiming socially-engaged practices for the white (or black) cube. In times of change, the institutions of art have to be assured of their relevance. Groys has gone further, contending that the shift from artwork to art documentation is symptomatic of the broader transformation toward biopolitical production, registering the move from artistic representation to real presentation. There is, however, a crucial distinction to be made between works that document art events or processes and those that are produced specifically for the gallery’s walls, for it seems that when the camera enters the field of social relations, the ethical dynamic is often transformed. The process of bringing social interventions back inside the walls of the institution by means of the video or photographic record either introduces an additional ‘layer’ of audience or, more usually, fully displaces the participant with the viewer, once again reducing the former to the position of subject. When asked by an unnamed villager when they would be able to see the film he is making, Martens replies never, that it will only be shown in European art galleries. These works are aimed at geographically and temporally remote viewers. Bacon’s Dog and Episode III - Enjoy Poverty are disquieting precisely because they set up uneven power relations; the artists exploit their position and, rather than attempting to engineer a genuinely equal collaboration, deliberately reveal the nature of the transactions that underpin production. While in Marti’s case the artist trades his own labor in the form of a sexual service for the opportunity to expose, the economy that Martens frames is one of pure extraction. It is in these transactions that we find the complex knot of ethics and politics that lies at the crux of the works.

Martens’ belligerent performance examines the contradictions of humanitarianism; claiming that poverty has become the Congo’s most valuable resource, he dwells on the excessive branding and competitive spirit of aid agencies as they fight over the cash that comes with visibility. He shows that when understood in terms of rights and charity, the ethical response is entirely subordinate to the dictates of capital. At the same time, his careful construction of the perpetrator/victim scenario engineers an ethical critique of capitalism by transforming the victim’s relationship with an abstract system into an ethical relationship with the artist: problematic political and economic relations writ small become repellent ethical relations.

The scale of the encounter is also a crucial feature of Bacon’s Dog. The curious mixture of generosity and violence that pervades the video seems to capture well the complexity of the relationship between public and private spheres at the outset of the 21st century. On one hand, the exposure of the ageing, queer male body speaks directly to the history of identity politics, which saw artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, Mary Kelly, and Nan Golden identify the private world as a key battleground for politics. The divide between public and private social life was understood as oppressive, and strategies which rendered visible hidden or counter realities were considered to be emancipatory. Fast forward to today; the voracious appetite for other people’s intimate encounters has seen biography and subjective narrative and sexual stories fill the pages of newspapers and television schedules. When the forceful emergence of the personal into the public sphere is now most commonly held in the domain of ethics rather than politics, does the public articulation of intimacies still retain a radical potential?

BAD BOYS

There can be little doubt that ethics has risen to new levels of prominence in today’s culture. Ethical committees proliferate across our institutions, ethical issues dominate both the media and political arenas, and the term has been resuscitated within academic discourse. Perhaps, then, it should come as little surprise that artistic practice has both mirrored and reacted against this tendency. But if Martens, Marti, and others like them join a long lineage of artists who have railed against ethical strictures, this can’t just be seen as part-and-parcel of the continuing legacy of the autonomy of art which demands transgression by explicitly linking it with originality and therefore success. Alongside a measure of spectacle, abjection, and shock, they register the shift that the ethics of aesthetics has undergone in the biopolitical age. Breaking away from the historical fascination with the production, consumption, and dissemination of images, these artists have moved into the realm of ethical relations. Any critique of the art of the encounter needs to consider afresh the new interfaces that emerge between ethics, aesthetics, and politics. Art’s bad boys may be back, but this time they’re going to make us think about the biopolitical and the bioethical together.

WORKS CITED

- Groys, Boris, Art Power, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

- Wright Stephen, “Users and Usership of Art: Challenging Expert Culture,” eipcp, 2007. <http://transform.eipcp.net/correspondence/1180961069#redir>