« Features

The Multiple Media and Modes of Visibility of Mickalene Thomas

The Brooklyn-based artist Mickalene Thomas creates visually arresting works in which she often gives African-American women a starring role. Her large-scale paintings, collages, installations, photography and video work take on the popular portrayals and stereotypes of black femininity and boldly answer back to them using her keen eye to break limitations. Not surprisingly, her work has caught the eye of the art world and found appreciative audiences in the past few years, most recently through her individual exhibition, “More Than Everything,” at Lehmann Maupin this past month and through a MoMA-commissioned piece prominently shown in its 53rd Street window.

By Maja Horn

Maja Horn - In your current exhibit at Lehmann Maupin you are exhibiting collages that are preliminary studies for your paintings. They are smaller in format than your paintings and provide a glimpse of the entire process behind your work. Perhaps because they are smaller in format, some critics speak of a certain restraint in this exhibit in comparison to others, for example your spectacular mural for the MoMA. Christian Viveros-Fauné suggests in The Village Voice that with this exhibit you have taken time ‘to stop, look around, and reassess.’ Is this indeed such a moment for you in your career and trajectory as an artist?

Mickalene Thomas - It’s not necessarily restraint, so much as stepping back, analyzing and reassessing what I present to the public and not reformulating what I do. Collage is something that I’ve always worked with. It’s part of a process for the work, and it’s just the first time, I think, that the public has seen it. What was important for this exhibition was to have the public see this side of my practice, to present that side of the work that you don’t necessarily see in the paintings. Also, this show was more about allowing myself time to think about how I want the next body of work to go.

M.H. - So the exhibition is indeed a turning point?

M.T. - Yes, it is a turning point. Deciding to make a show entirely of works on paper was a big leap for me. Plus, I was at a residency for three months this past summer in Giverny, France, and I couldn’t bring all my materials there. So I started thinking about my practice-why do I consider my practice just my paintings when in my studio that’s not all I do? So, why don’t I just bring my collages, my collage materials and do that work there? That is something that I do here anyway, prior to the paintings: I build installations, photograph the models and then from there select the body of work from the photographs to make the collages.

M.H. - The collages are then an intermediate step?

M.T. - Yes. I have assistants that come and help me with the paintings. There are certain things that I need assistance with, but the photographs and the collages are something where it’s just me. I’m excited that my work has gone to this new level, and there is a lot of exposure, but with that exposure, with that demand, comes the responsibility of realizing, ‘Ok, I have more work to do.’ I am only one person. With the collages and photographs I don’t need help with production, and they are so tangibly and intrinsically about me, and my hand, and so I thought it was very important for the show to present them, because the paintings are about a different visual power and experience.

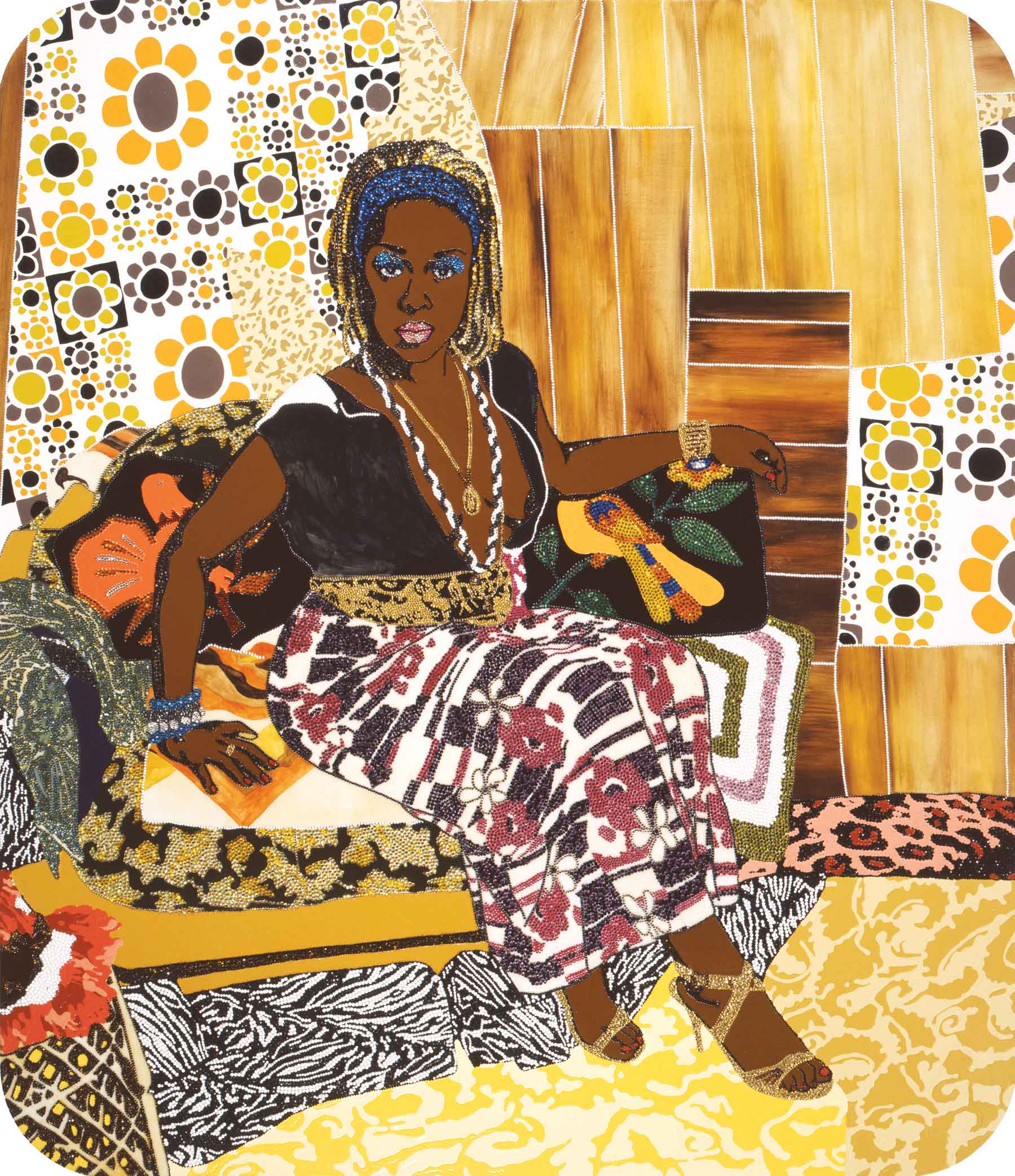

This Girl Could be Dangerous, 2007, Rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel on wood panel, 84” x 72.” © 2009, Mickalene Thomas.

M.H. - I think both because of the multilayered process of your work but also because this exhibition gives a glimpse into your process, there have been a lot of observations about what the sources of inspiration are for your work. I have been struck by the wide range of influences that critics detect in your work, such as blaxploitation movies, Romare Bearden, David Hockney and the history of the portrait in Western culture. I think what this range of references reflects, some referring to your elaborate landscape or scenography and some referring more to the stylized human protagonists, is how these two aspects can’t really be separated.

M.T. - For me it is important to look at all of those aspects. It comes down to what I am interested in, and how you put your experience into your work, your inspirations and aspirations. I think your work is an extension of yourself, so it is just inevitable to use those things that you are interested in and take from them and come up with your own language within that language that already existed before you.

M.H. - Are there any other sources of inspiration that I missed?

M.T. - I think there is a little Alice Neel in it when it comes to the line. I had a gallery dealer say to me one time, ‘I am really interested in your line-have you really thought about the line quality in your work?’ I remember that, and I was wondering, what does he mean? He was looking at a body of work that I did at the Studio Museum, and I think it was Jack Tilton who said that to me. He has been a great supporter, and he has been looking at my work for a very long time. Obviously, he was talking about drawing and how it moves and the plane of the space that you are creating. So I started looking at Alice Neel and people who I was interested in that had a great line in their work and what that means. For me, if I was going to look at anyone’s work and consider the line quality, it was Alice Neel, and I continue to look at her.

A lot of my looking at these artists has to do with very specific information that I am interested in pulling from their work. It is very specific. When I started looking at David Hockney-I saw his show at Pace a couple of years ago, his landscape paintings-I was very interested in how he used the grid in his work, but also how the space shifted with the colors and the landscape. I was already doing landscapes then, and I always felt that there was some connection between my work and his, but I never really looked at his work until I saw that body of work at Pace. So, there are very specific reasons why I look at someone’s work, and it just seemed obvious to me, when I started really thinking about collage, to think about Romare Bearden. One, because I am an African-American woman, two, because I have studied art, and I think he is one of the best when it comes to concepts and formality. I thought he was just perfect at that time to reconsider. A lot of times it is a matter of reconsidering these artists; they are out there, they are in the ether of my mind, but I sometimes never even thought of them until a particular body of work is expanding in my studio and I think, ‘I need to look at that person.’ You have to listen to what is happening in the studio, and that guides me.

M.H. - When people talk about influences in your work it is about certain visual references and proximities. I want to talk about an artist whose work visually is not in close proximity, but I think you share similar interests and perhaps an ongoing conversation about black femininity, and that is Kara Walker. She also wrote a review of your work in BOMB Magazine, and she herself placed you in that conversation. Interestingly, she had a show at Lehmann Maupin and a concurrent show at Sikkema Jenkins where she evoked 20th-century black divas with a different approach but nonetheless there are few points of contact.

M.T. - Yes, I think that her silhouettes come out of a long history of a different type of collage, of what may be the first essence of what collage is: of taking the image and resurfacing it and the positive and negative relationships of space, because they were cutouts. Kara Walker is very much an important figure in the art world, and I can definitely say that I have been interested in and inspired by what she has done. I considered how she used history in her work and how she related that history to who she is as a black woman, using the black body in a completely different way, and it was not even in a post-black way, it was beyond that. She was pulling towards a history that no one really wanted to talk about, which was very controversial, and she got a lot of backlash for that. I was inspired by all of that and respect her for it immensely. Looking at her work was also about very specific things; it was mostly about how she was able to take two formulas that were very extreme formulas and bring them together and put them in her work, and I was very interested in that dichotomy and how one would do that.

M.H. - There are a lot of observations about the multiplicity of your references, your materials, your artistic process, but I have noticed that the conversation about what arguably is your main theme, black femininity, is less attentive to the multiple forms of visibility, specifically of black female visibility that you engage with that cannot be reduced to one form of visibility. What is mentioned, for example, are ‘romanticizing’ ideas of black female power or your re-working of certain stereotypical images of black femininity, and words such as ‘luxurious’ or ’sensual.’ I think your work poses a really important challenge, both to the audience in general and to critics, to be more thoughtful and more attentive to the complexity with which you address black femininity and the different modes of visibility you employ. For example, the kind of visibility that emerges in your photos might not be exactly the same as that of your paintings.

M.T. - I think this is why I oscillate between so many different mediums. Painting will only allow you to depict the image so much and so far, and photography has a different presentation. Painting becomes more of this fantasy. It is really what I want it to be. It has nothing to do with the real image itself. Photography manipulates the viewer into thinking that this is what it is. It resides in that reality of what is ‘true.’ There are elements that I cannot get in a painting that I know that I could achieve in a photograph. That is what interests me about the different materials, and I recognize that, the possibility of what I can achieve with different materials. What is interesting and fun for me about collages is that you can bring both of those elements, the truth, the manipulation and the fantasy that you can make into that essence that you want to present, because you can use images that seem true like a photograph. For me that is what is exciting about working with the various materials and why I introduced video. Video allows for a whole different level of experience that you cannot get with a photograph, because a photograph is a very static and still moment that you capture in time, a particular time, according to the one behind the lens. What video does, [it] plays with the same techniques, but it captures the essence in a particular motion that can be manipulated later in the editing process. It presents to viewers ‘the fact’ of something. So, I am interested in that-how, basically, the media and the medium that you use is the message that you are presenting to the viewer. I think it’s very powerful to understand that.

When I start working with a new medium, I have to really find a relationship that gradually takes me into that process and direction. People have said to me, ‘Have you thought about sculpture?’ And, of course, I have thought about sculpture, but it has to metamorphose out of the practice itself. I have attempted and I have tried, but I just haven’t found the right way of presenting it with how my work is developing. The photographs came out of that same practice. I was already using them as a resource material, from that it developed into recontextualizing how I see these images, and they are no longer just resources. Now my installations are becoming that way. Maybe the sculpture is purely the installation, period.

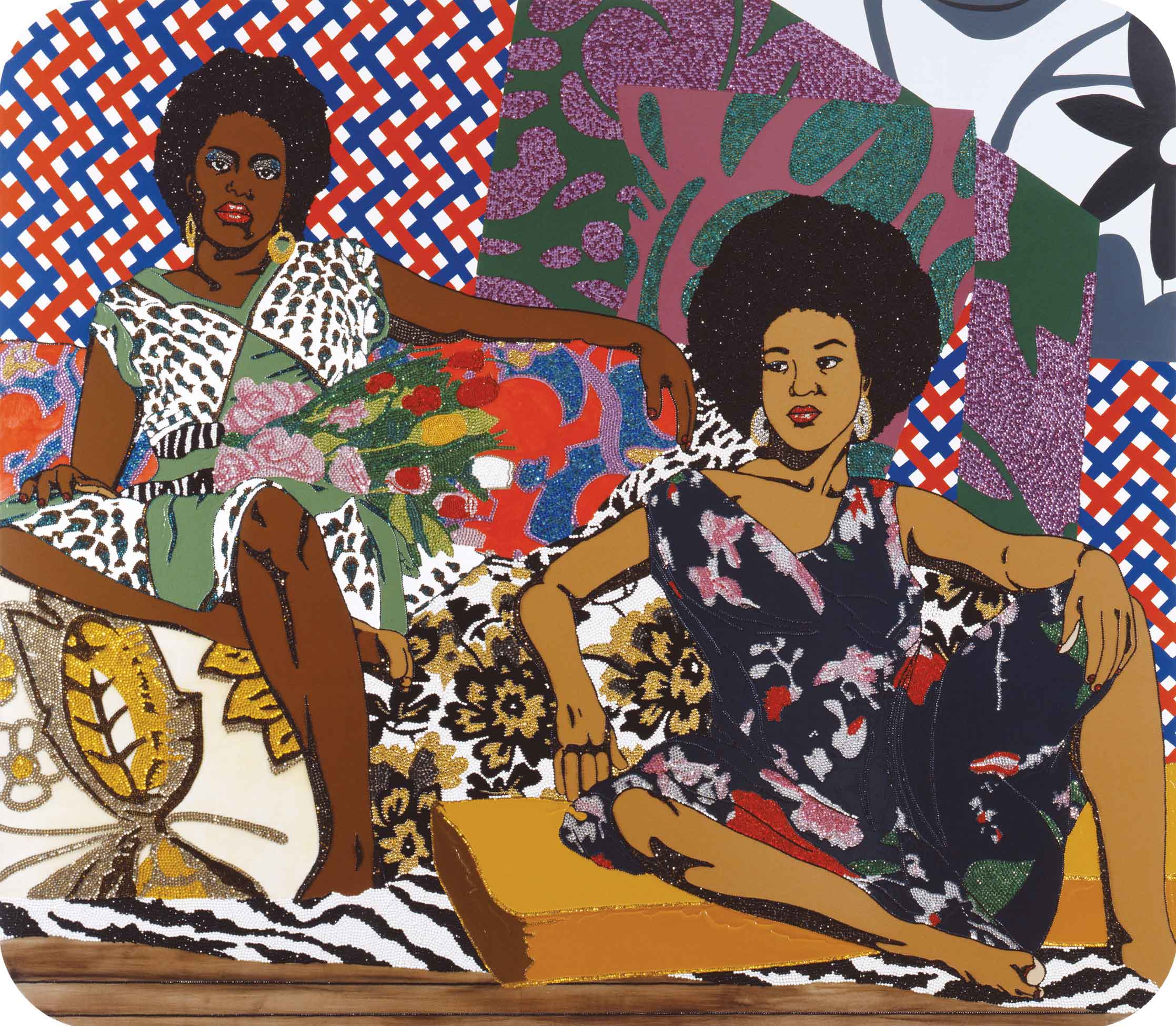

Moment’s Pleasure # 2, 2008, rhinestones, acrylic and enamel on wood panel, 72” x 84” © 2008, Mickalene Thomas.

M.H. - I recently came across a book by Touré called Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness: What It Means to Be Black Now in which he suggests that ‘to experience the full possibilities of Blackness, you must break free of the strictures sometimes placed on Blackness from outside the African-American culture and also from within it’ (4) and then, not unproblematically, he also suggests that being post-black (though not post-racial) means being like Obama. This made me think about your portrait of Michelle Obama and wonder can one translate the message of this painting as saying to black women, ‘We should be like Michelle Obama?’

M.T. - When I did the portrait of Michelle Obama it was before they were inaugurated into office. Mainly because-I am pro-woman everything-on the level of which they were placing Obama, placing him on the same pedestal as a John F. Kennedy, it led me to think, If Obama is sort of a JFK, wouldn’t Michelle Obama be like Jackie Onassis?

M.H. - That is why the title of your portrait is Michelle O.

M.T. - I was doing this project, and I wanted to portray what she represents, and I would have never have made that reference if they both weren’t amazing women, for many different reasons. They both were pioneers and very amazing spokespersons and really changed and shifted how we see the world, and then, of course, the comparison of them in fashion. Also, for me in terms of what Michelle O. represents, I think she has more of a responsibility than Barack has. I don’t think people realize that. Obama is a black man, and black men have already prevailed certain ‘isms’ beyond black women. Black women today are probably more educated than black men-for reasons that require a whole different conversation-percentage-wise black women are the ones going to college more, yet, there is still this image that is placed on black women. Before Michelle Obama we had someone like Condoleezza Rice, who was still placed in that role of the angry black woman, and then you had the image of Oprah, who was the mammy of black women, that maternal aspect of her and Michelle O. was neither of those things, and I found that very powerful. People are looking at her as this fashion icon, and this highly intellectual person, and respecting her, and looking at her beauty, and they weren’t sexualizing her, all of these things that I thought were phenomenal. For me it was just really important, because there were all these images of Barack Obama and nobody was doing images of Michelle Obama. I just did it because I wanted to; it was not a political statement. It was not about social change, it was about respect. I wanted to use art history, take from Andy Warhol and how he related to icons, thinking of his portraits of Jackie O., and it made sense to me for it to unfold in that way.

M.H. - So there is something about Michelle Obama and what she represents, not that all black women should be like her, but that represents a different form of female black visibility that is pointing in a good direction, and that you find very powerful?

M.T. - Absolutely.

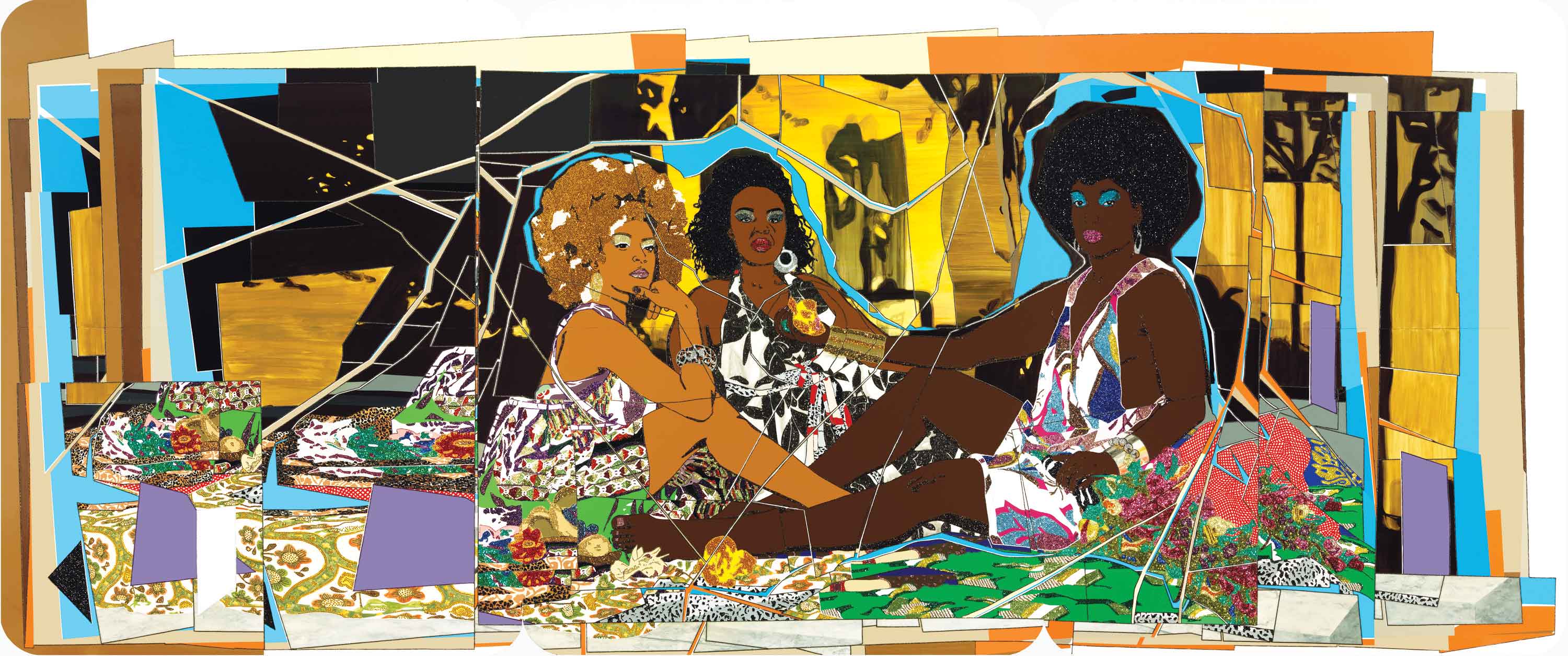

Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires, 2010, rhinestones, acrylic and enamel on wood panel, 120” x 288” © 2010 Mickalene Thomas.

M.H. - Is there anything in your work that is personal, biographical that we don’t know about yet, that is in the work and hasn’t been noticed? Of course, in some way all your work is personal.

M.T. - Yes, they are all about me, mostly. I think portraiture always goes back to the maker, how they see themselves or want to see themselves. The way in which I construct my paintings I think comes a lot from, one, me being a woman and two, from really dealing with where I grew up, how my grandmother did things. The personal thing for me is when I started making the paintings, and particularly the installations, I started thinking about how my grandmother used different materials to reupholster her furniture. I always found that very interesting, because she was never really interested in buying new furniture but reupholstering it or patching it up. This is why I initially started using fabrics in the first place and how the faux paneling came in. It was not necessarily that I was so interested in blaxploitation as an entry into the work, it comes from that, but I wasn’t really thinking about it. I was just thinking about my experience as a kid and what inspired me. I was pulling more from my childhood than blaxploitation. I was taking elements that I remembered as very powerful, like the afro, the faux paneling, the patterns that I was surrounded by and putting that into my work. Then I started using iconic women, like Pam Grier, and what she represented. It didn’t come from Pam Grier first, it came from me pulling elements out of my childhood, and that is why I use the wood grain a lot-the faux paneling is a representation of these environments that I was surrounded by growing up.

- This interview was held on October 28, 2011.

WORKS CITED

- Christian Viveros-Fauné. “Boom, Bubble, Bust: Matthew Barney + Jenny Saville + Mickalene Thomas.” The Village Voice. 5 Oct. 2011.

- Kara Walker. “Mickalene Thomas.” BOMB. Spring 2009.

- Touré. Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness: What it Means to Be Black Now. New York: Free Press, 2011.