« Features, Uncategorized

There is a light that never goes out. An Interview with Julio Le Parc

Julio Le Parc is considered one of the most important artists of the 20th century, a once young creator who migrated to Paris to become a leading voice among artist-activists and a pioneer in the use of light and color in his works. A relentless researcher into the field of art-as-experience who famously rejected a 1972 exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Le Parc has recently been the subject of a number of retrospectives at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris and Casa Daros in Rio de Janeiro. In this interview, Le Parc looks back on his early years in Paris, reflects on the importance of politics, changing technology and collectors’ ever evolving whims. While his plans to return to Buenos Aires for good were interrupted by the military junta that took over Argentina in 1976, he’s still looking forward to working in his native city, and with an upcoming show at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA) next July, his wish just might come true.

By Marina Reyes-Franco

Marina Reyes-Franco - What was the panorama of the visual arts when you left Argentina? What were you looking for in Paris?

Julio Le Parc - Among the things that characterized the panorama of the visual arts in Argentina-particularly in Buenos Aires-as well as that of other Latin American countries at that time, was the myth of art created in Paris. We, young painters, received varied and contradictory information and evaluations with respect to the art which was produced there. A small group decided that our only alternative if we wanted to find a place within that panorama was to see it for ourselves. I applied for a scholarship from the French Government and, luckily, it was granted to me, although they did not know my work very well, and so I could come to Paris in 1964. I arrived on a 4th of December.

M.R.F. - When you make reference to a small group, who are you referring to?

J.L.P. - We were all friends in that small group. Some of us had already met before, when in 1955 we organized a movement comprised of students from the three art schools, occupied the schools during a whole month, and requested that the art orientation was modified, the teachers and the director be removed and replaced, that new plans for the teaching of art be devised, etc. Among the friends who gathered together at home were Francisco Sobrino, Hugo Demarco, Horacio García Rossi and Sergio Moyano. On Saturday nights, after having finished the work and the school week, we debated amongst ourselves, and that is how we decided to travel to Paris.

M.R.F. - What was the context in which your artistic practice began, particularly as a member of the GRAV? What did the GRAV members pursue?

J.L.P. - Well, when we arrived in Paris we went on with our practice of debating amongst ourselves, comparing what we did and analyzing the context of artistic creation in Paris. What was found there at that time, and which later arrived also in Buenos Aires, was the so-called Informal Art, or Lyrical Abstraction, a kind of academicism that had invaded the totality of galleries and biennials. We made our proposals with the aim of opposing this fashionable phenomenon and breaking with that monotony. We were concerned with determining what our situation was as young artists within that context, how artistic creation was justified and hyper-valued, how the artist considered these justifications, what gained him/her recognition from art critics, galleries, museums and international exhibitions, and how the art market worked. Then, one of our possibilities was to continue analyzing all these issues as a group, devote ourselves directly to our own production, and see if with this production as our point of departure, we could try to discuss and overcome this situation. It was not a question of producing supposedly artistic and genial works, but works based on experimentations and searches. Instead of pretending to be superior artists, we were only experimenters, and instead of aspiring to sell our works at all costs, we wanted to continue with our searches. Instead of becoming locked up in individualism, we tried to continue with the group work, pursuing the creation of collective works. Among the GRAV members there were French artists-like [François] Morellet, Stein and Yvaral-with whom we worked until it dissolved.

M.R.F. - What influence did the political and social environment of the 1960s have on your artistic concerns?

J.L.P. - Everything that I mentioned before was of a political nature, because that questioning within the visual arts was a reflection of what was happening in the other dimensions of society.

M.R.F. - Would you say that what you saw was that it was possible to experiment with art in order to bring about major changes in society?

J.L.P. - We did so within our own production; we no longer sought support or recognition from art critics, gallery owners, museum directors or collectors, but rather worked and experimented in a collective way, trying to create a direct relationship with the viewer.

M.R.F. - Perhaps the most important thing is to modify the relationship between artists and the way in which they see one another.

J.L.P. - Individualism was one of the pillars on which that system was based. The more individualistic or the more competitive and antagonistic artists were amongst themselves, the easier it was to manipulate them, and select them, and promote them.

M.R.F. - In 1968 you were expelled from France due to your participation in the Atelier Populaire during the May 1968 events in that country. Then in 1970, you organized a protest at the San Juan Biennial of Latin American and Caribbean Engraving in Puerto Rico. Your intervention led to the exhibition of a text dedicating the biennial to people’s liberation. What other actions or works independent of your artistic production do you remember having carried out with political or protest intentions?

J.L.P. - There were many things, because after 1968 there were different actions, as for example the boycott we carried out against the Sao Paulo Biennial [1969], because the military were exercising censure, and a Brazilian artist [Hélio Oiticica] visiting Paris informed us of the situation. Then there followed many types of actions, denouncing the coup d’état in Chile, helping the families of political prisoners in Argentina or supporting the committee, which was created to denounce that situation via French lawyers and jurists. Sometimes we made paintings, as for example the one against Pinochet at the Venice Workers Union, or another in favor of the fight of the Sandinistas against [Anastasio] Somoza, or denouncing torture in Latin America.

M.R.F. - And do you consider those works are also part of your artistic production?

J.L.P. - As I said before, I consider my production is experimentation and a search for the relationship between an artistic proposal and a spectator, trying to arrive at a quasi-coproduction.

M.R.F. - You have always maintained a critical stance with regard to the mechanisms that govern official culture, those that determine the value judgments about what is valid and what is not valid in art, what can be exhibited in a museum, or the way in which a work of art must be appreciated. It is possibly for this reason that you developed a kind of art that involves the active participation of the viewer, allowing him or her to have the last word when interpreting the work in question. This condition contributes a political component that is intrinsic to your work.

J.L.P. - In general, it is good to highlight this condition because there are many artists who consider that when figurative work does not denounce a situation of injustice, it is not work of a political character. Not long ago, I had a discussion with some figurative artists. For them, what I do and all the experiences I have implemented have no political content because, in their opinion, they are neutral things, and what is political is to portray in a painting the star of Che Guevara’s beret or a closed fist. Only this type of thing is valid, and I do not mean to say that this is not an option that may turn out to be interesting, but I do not agree in considering that you can do something of a political character exclusively through this kind of figuration. In my particular case, since I was a teenager I was interested in, and also respected, the position that prevailed in the 1940s in Buenos Aires, the group of artists who painted the frescoes in Galerías Pacífico-Berni, Spilimbergo-and who reflected in their paintings themes related to social injustices and had a progressive stance from a political point of view. At the same time, I was beginning to discover the Arte Concreto-Invención group, with Maldonado and all the rest, who also declared they had a left-wing political position, not only through figuration but also through the use of simple geometric forms.

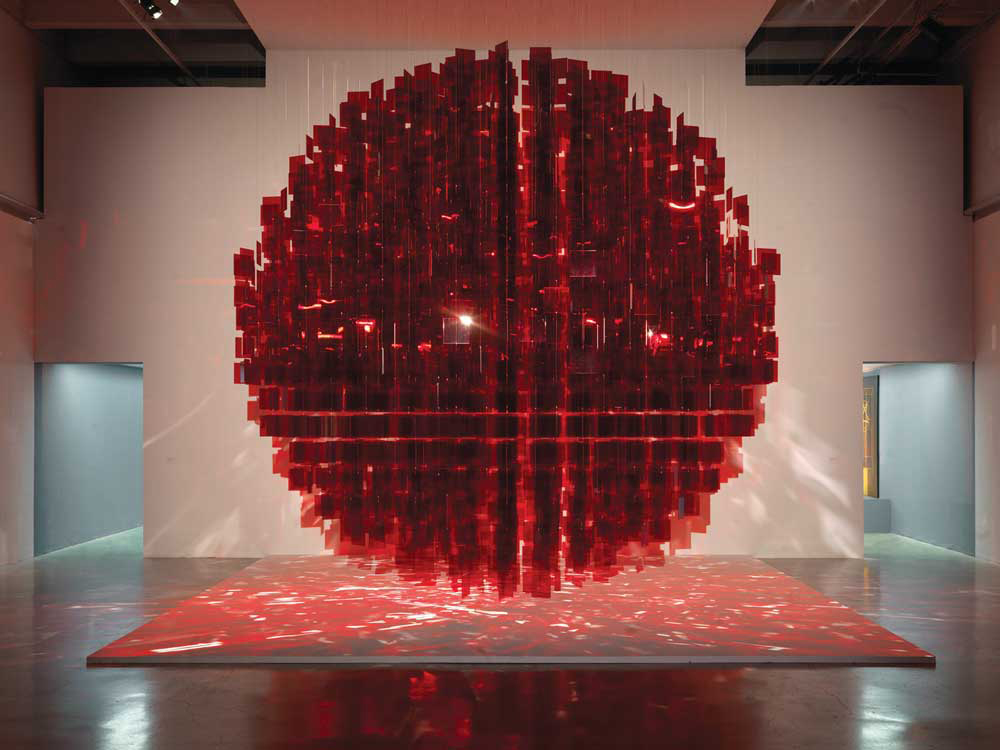

Julio Le Parc, Continual Mobiles, 89” x 158” x 158.” Installation view from “Nouvelle Tendance,” Palais du Louvre, Paris, 1964. Courtesy Atelier Le Parc and Lélia Mordoch Gallery.

M.R.F. - It does not surprise me to learn that these same discussions regarding whether figurative art is the only art that can be political, versus another kind of work still persist. I think the discussion should be oriented towards what kind of relationships we establish in order to work. There are many different ways of being political. Here in Buenos Aires there are many initiatives headed by artists who cannot depend on a government or a gallery.

J.L.P. - Some years ago, after the Corralito, I went to the San Martín Theater in Buenos Aires because they had found a mural of mine, deteriorated, in a cellar. The people at the San Martín Theater proposed that I should deliver a lecture, but I told them I did not want to speak, yet I did want to listen, because after that very strong economic and social crisis, there appeared, little by little, groups of artists. I think there were around 20 groups that came and presented their works. There were different levels of execution, ranging from those who made posters for the social movements to those who made books using recycled paper.

M.R.F. - Eloísa Cartonera.

J.L.P. - Yes, there was them and there was another group from La Plata.

M.R.F. - Surely, the Taller Popular de Serigrafía (Popular Serigraphy Workshop) was there.

J.L.P. - Yes, that one too; it was very interesting. Usually those proposals do not fall within the normal art context of galleries and museums, but they are actions performed by young people with great creative capacity, whose trigger is a social situation.

M.R.F. - This situation made Buenos Aires arouse international interest. It was a crisis that led these artists to start working collectively and to contribute very valid proposals. How often do you return to Buenos Aires?

J.L.P. - I go there when I have to do something or when I am invited. I do not have the same habit as other artists who keep an apartment and go there once a year. In 1973, I bought a house in Buenos Aires with the idea of going there more often, but then things got difficult and the house remained unoccupied and I eventually lost it. I did not go back until the military left; I think I returned in 1984.

M.R.F. - You did not return for over 10 years.

J.L.P. - I think it was 11 years. I bought the house to set up a studio and to return with the whole family, but that was not possible. Now it is too late, but every time I return to Argentina I do so with the idea that if I had a place, I could remain longer in the city, do things and work with the people. Each time I go back, I have that idea.

M.R.F. - I would like to know how you ended up making light another art medium, a medium through which to create art, with which to modify the space and challenge perception.

J.L.P. - The fact is that I did not say to myself one day, “I am going to work with light.” Rather, my concerns and the small experimentations I was carrying out at that moment guided me; for example, the permutations of a 14-color gamut that I had created made me realize the way in which the planning schemes varied. Every time, the variations that could be obtained multiplied. My concern was how to highlight the variations-there were some that produced 20,000 variations. If I wanted to achieve this through painting a gouache, it would take me 30 years. That concern about the way in which I could highlight such a large number of variations led me to create a series of machines to be seen on a prismatic screen with a flashlight bulb. Little by little, different situations were generated which gave rise to others. I tried different things. It was also a way of not being monothematic. Generally speaking, in those days there were many artists who sought to differentiate themselves from others through a small particularity. I recall I saw an exhibition of works by Chagall when I came to Paris, and I realized that he had painted practically one picture throughout his life, at first a little bit cubistic, more or less geometric, then increasingly more liquefied, but it was the same painting. It was alright, I continued to like his paintings, but he was a monothematic artist. There are many artists of that kind, and people go on buying their work. On the other hand, the wish to experiment and search in order to satisfy curiosity gradually led me in other directions. Thus, my first experimentations did not involve light, but rather, light was a support to solve certain concerns. I realized that other things could be derived from that, and with this attitude I increased experimentation with light, and light became more important in my work.

M.R.F. - Besides, coming as you did from the field of painting, it is no wonder that you should think of light.

J.L.P. - At that time it was only a means that helped me find solutions. Well, then came the whole interpretation of this aspect: if light has a mystic component, if it is the basis of life, that without it we would all be blind, that if light is used in a certain way, it generates a particular transcendence. These are other speculations, other considerations. In my case, everything was always the result of relating one element to another-a source of light to other elements that produced variations.

M.R.F. - The technology you used in those first works is fantastic, precisely because of the utilization of everyday elements such as nylon thread, pieces of wood and metal, optical lenses, domestic lamps, apparently simple solutions which, however, require profound knowledge of physics. Could you share with us some anecdote of that first stage of experimentation with light and space?

J.L.P. - I had no knowledge of physics or of mathematics. None, except for circles, squares and triangles. Everything was done in an empirical way. Sometimes I received a small electric shock, and many of the solutions depended on the scarce resources available, what I could buy: little pieces of wood, a bit of plastic, sewing thread, the kitchen lamp, but always within those limitations. For me it was important that the results should be valid for themselves, and not because of the mediums I used. Some works belonging to the so-called technologic art which I have seen in exhibitions showed an overflow of technology involving computers, projectors, videos, but when you seek their meaning, it is as if they were a sample of technical possibilities, and at the core, in the case that there actually was a background of creative art, it is drowned by that excessive presence of technological elements. For me the result is valid. If advanced technological elements are used, if they are well used, if this has a strong result-whether it is poetic or participatory-if it attracts the viewer or creates an atmosphere of imagination, it seems valid to me. Sometimes they rely on technology alone, without revealing anything else.

M.R.F. - You use more state-of-the-art technology these days. Do you consider that you are modifying your more recent work, precisely since you are saying that at the beginning you worked with whatever you could obtain or had access to? How has your relationship with that technology varied?

J.L.P. - Logically, technology is present, in one way or another, be it because the lamps are currently better, they are smaller, they radiate less heat; this is a technology that did not exist before. To make montages of things, if I have more advanced resources at hand I can scan drawings or reduce them or enlarge them.

M.R.F. - There are elements you used in your works, which are no longer produced and are difficult to replace.

J.L.P. - Yes, here, for instance, the light bulbs I have used since the 1960s-incandescent-have been withdrawn from the market. The filament those bulbs used to have was the basis of many of my works. Then came the halogen light bulbs, and now we have the LEDs, which are replacing them and in some cases are equal or better. The micro-motors I used had their limitations, because each of the engines had its own speed. There are some new micro-motors whose speed can be modified through the use of a single motor.

M.R.F. - If you have to replace something, you have no problem with that.

J.L.P. - I have no problems, but art collectors and fetishist art admirers do. What is important for me is the visual presence of the work, and not if it has or does not have the same components as when I first made them; what is important is that the result is the same. As I have already mentioned, it is meant for some fetishist collectors, who think that if the work does not include the light bulb of the 1960s, it is as if it was distorted. Whether the work’s support is a wooden panel, or whether that wood is new or dates from the 1960s, it is just irrelevant. Sometimes they say it is not the original panel, and this sort of detracts from the value of the work.

M.R.F. - In what way do you suggest that the public should approach your work? How can we go beyond appearance towards experience, with the utopian connotations you suggest in your works?

J.L.P. - Each time I stage an exhibition in a public place, I try to put into practice something that will allow me to obtain the public’s participation through what I do, and, besides, to make this participation reflexive. Many times I have attained this aim through a questionnaire that I have placed at the public’s disposal, and I have obtained a great number of answers. Other times, with the pretext of donating a work, I have got the public involved. Once, in an important Madrid venue [Sala Pablo Picasso], I said that I was going to donate an artwork to the Spanish people, and I told the director that I wanted to have a survey, and that visitors to the exhibition should vote and choose the work I would donate. The director hit the ceiling. “What? I am the one who has an academic background, I am the one who has a career in the art milieu, I am the one who has directed this museum for so many years, I am the only one with the capacity to choose a work for this museum. How can the public walking down the street or visiting the exhibition by chance have the capacity to choose a work?”

But I said, “Do not worry. Let us carry out the survey anyway, and then we will see.” In the end he let me implement it, and I was there, and it was interesting to see how, from the moment the posters requesting an opinion appeared at the entrance, people’s behavior changed. It changed from that of the spectator who enters a museum, looks and leaves, to that of the spectator who completes the survey and is committed. His/her visit is no longer the same. Spectators say to themselves, “If these people are asking me to give an opinion, it means that they are taking me into consideration.”

The curious thing was that when the votes were counted and I organized a discussion with artists from Madrid, the director was surprised when we told him that the work the public had chosen was, let’s say, number nine. The director exclaimed, “That’s impossible, Julio, that was the same work I would have chosen.” He thought the public was not capable.

M.R.F. - Your works, particularly those based on the use of light, are incredibly apt to be photographed, yet at the same time, since they are constantly changing, they can never be completely recorded. These days, when almost everybody has a mobile phone with a camera or when we human beings have become used to looking through a viewfinder, in what way do you think the artistic experience is altered? Do you think this affords people more possibilities for recording and experiencing, or on the contrary, the individual is removed from immediate experience?

J.L.P. - Do you want to ask me if it is easier to photograph?

M.R.F. - Well, the fact is that, lately, you go to a concert and people are recording the concert with a mobile phone. There was a Yayoi Kusama exhibition here in Buenos Aires and it was impossible to view the exhibition because everybody was taking pictures of it or taking pictures of themselves reflected on the works. On the one hand, photography offers a wide range of possibilities of recording the works and of having a different kind of experience through the use of this new technology-cameras and applications.

J.L.P. - But both things can happen: the public feels attracted and participates in the show, and at the same time it is recording the show in order to take it home. If somebody enjoys a particular sunset and he/she records it, it is a way of appropriating the scene and later he/she can also show it to others. The possibilities have only multiplied. Insofar as this new possibility is not superimposed and does not hinder the direct relationship, it is a new type of relationship they are creating with other people based on what they see at the exhibit. I do not criticize that. Do you?

M.R.F. - I think that a new relationship has been created and that it is also a new way of sharing the experience with more people. I find this valid, and I partake in it. Besides, I do not like museums that still maintain the ban on taking pictures. Obviously, you do not take a picture with a flash of a work whose conservation may be affected. I very much like museums like the Rijksmuseum in Holland, which opened its collection, and now all the works are available online in high resolution. This becomes a work tool for other people, as in the case of artists who work with image appropriation or modification. But on the other hand, I think there are exhibitions that show works that are visually very attractive, and people find this satisfactory; they do not delve deeper into the work or investigate what led the artist to create it.

Well, let us continue. When you were distinguished with an award in the 1966 Venice Biennale, critics pointed out that your work was ‘an art without frontiers.’ As an Argentine artist who has lived in France for so many years and who is, at the same time, part of the history of Latin American art, what is your opinion about these categorizations by countries or regions?

J.L.P. - In general, categories are always superficial. Grouping within the same style-Op Art, Kinetic Art and all the rest-they are artificial. Grouping by styles is the same as organizing salons based on the use of watercolor technique. Even in geometric art, works may be repetitive, monothematic and grouped together only because they use geometry. If an artist is French or American, this can be complementary information about this artist, and sometimes in a next stage it is good to know if an artist lives, has died, or if he/she lived in such and such a place, or if he/she was in touch with such and such artist or if he/she replies in this way to the questions of the art history of a faraway country in South America, for instance.

M.R.F. - There was a time when homogenization was pursued. There were critics who were very radical, and if you had other references or used certain materials, you were already an imperialist. A critic like Marta Traba was very cutting about that. In Argentina she did not have much influence, but she was influential in Puerto Rico, in Colombia.

J.L.P. - Yes, and in some countries of Central America. I could never understand what they would consider that to be the ‘true’ Latin American art. If you see the work of the Mexican muralists, they reflect the influence of the European cubists, as in the case of Diego Rivera, or of the Italian Renaissance artists. I wrote this in a text once: The true Latin American artist is that Indian who belongs to a tribe that has not yet been discovered in the Mato Grosso and is creating things with corn cane and leaves. That is the true Latin American artist, the one who is not under anyone’s influence. He does not even suffer from a cold.

M.R.F. - In your opinion, what are Kinetic and Op Art contributing in terms of strategies and resources to younger artists such as Anish Kapoor, Olafur Eliasson, Carsten Holler, Jeppe Hein, etc., whose work has drawn upon the legacy of artists of the 1960s, pioneers in working with light and physical space? What new things do you consider are being developed currently in this respect? Do you know them?

J.L.P. - More or less, not much. Once a museum director asked me what I thought about Anish Kapoor. I told him I did not know who he was, and he replied, “You don’t know what Anish Kapoor does, but Anish Kapoor knows what you have done.” Many of them are very young, and they can gradually evolve, but I do not assume that perspective. I do not pretend to be the great artist of light or to have influenced anyone. I see myself as someone who has done many different things. Perhaps the conducting thread is an attitude of research which has manifested itself in different ways. Certain indifference with regard to being pigeonholed through a production might be a precise conducting thread in my work. I would rather be identified with a set of behaviors, activities, attitudes, etc. Classifications as an artist of light, an artist of movement, a geometric artist, a kinetic artist, etc., are not effective, and many times they are arbitrary. From my point of view, they are superficial classifications. I never said I was a kinetic artist.

M.R.F. - With which artists would you ideally like to share a group exhibition?

J.L.P. - I am not interested in grouping by technique but rather by behaviors and attitudes that I deem worthy of adopting currently in this social universal context. There are artists who tend to be a little monothematic, who constantly repeat the same themes. In some cases, it is possible to transcend this repetition, and then the essence of the work is reached and it evolves, but in other cases, the works are mere formal repetitions.

M.R.F. - In 2013, your work received significant recognition; You had your first major retrospective in France, at the Palais de Tokyo, and “Le Parc Lumiere” was on exhibit early this year at the Casa Daros in Rio de Janeiro. What effects, both positive and negative, do you think your having refused to present the retrospective exhibition you were offered at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1972 had on your career?

J.L.P. - It was something I had to do. It was the only thing I could do at that moment-neither refuse nor accept the exhibition, nor think whether it would be positive or negative to do so; but rather, leave everything to chance. Leave the decision to chance as an external factor, but at the same time, a factor which had been my choice.

M.R.F. - Traditionally, the exhibitions programs of major museums include few exhibitions of artists from the so-called ‘periphery,’ that is, artists who do not hail from the hegemonic art centers. Nor are those artists usually included in compilations of contemporary art, in which one perceives a predominant presence of American and European artists. In your particular case, although you have lived in France for the past 50 years and you are one of the most important creative artists of the 20th century, it was not until 2013 that a French institution organized a retrospective exhibition of your work. What is your opinion of the way in which the mechanisms to validate works of art currently work? Do you consider that the interests of mainstream galleries and leading collectors exert an influence on the validation criteria wielded by art institutions?

J.L.P. - Of course they exert an influence. A collector who has an interest in a particular artist will try to use his/her influence so that this artist is represented in a major museum, institution or public place that adds prestige to his/her investment or private taste. Then there is this game among a group of very important collectors at a global level: If it is considered hip to buy works by artists from Latin America or from any other place, they will do so. Currently, there are very important collectors who are buying Chinese art because it is a trend. This art is outside the great centers like New York, London or Paris, but it falls within the same context. There is a tacit agreement among them, and depending on the importance of each of these collectors, wherever one goes, the others will follow. Acquisitions then become acts of legitimization of certain artists and certain trends. Sometimes they narrow down to a very limited number of artists who, merely on account of their work having been purchased by these collectors, seem to be the best, which is not actually true. At other times there was a market, but it was not as polarized as it is today. Sales were more diluted, and buyers were more discreet. The fact that a work of art should be legitimized through its acquisition was less violent. Besides, we had art critics, who remained updated with regard to the latest developments and could contribute their reflections, proposing an analysis of what was being done. There were art critics who identified with a trend and defended it to the death. In one of the first exhibitions we staged in the United States, they said it was ‘an exhibition for artists.’ It was a presentation that pursued a confrontation with other artists; it pursued a dialogue or certain complicity, rather than being an exhibition to be sold. Those other ways of appreciating art have gradually disappeared. Art critics have much less weight today, and the notion of exhibitions for artists is also gradually disappearing, because what prevail through their brutality are the huge prices that are paid. If everything boils down to sales, there is no artistic value, and this distorts any kind of relationship.

M.R.F. - Yesterday I was reading an article by Holland Cotter that referred, precisely, to the negative effect of money on the way in which art is seen or perceived, and he established a very clear difference, saying that when people write or speak about the ‘art world,’ they are not really referring to the art world but to the art industry. What these very wealthy people represent is the art industry, while the art world is represented by the artists who are working, not necessarily by those who are selling their works for a fortune or those who are presenting them in major auction sales.

J.L.P. - Of course.

M.R.F. - Viewing your website, it seems you feel a deep sense of historical responsibility with regard to the documentation of your artworks, your texts and all that has been written about your work. Do you have any observations or critiques regarding the way in which you have been positioned in art history?

J.L.P. - I think that as time goes by, you as well as other art historians can have a much clearer vision of what I have done, a more exact and precise vision than the one you could have had in the 1970s. I am delighted to see that there are a growing number of accurate opinions and analyses which in some cases go far beyond what I could have elaborated through my own reflection. By and by, we are arriving at a more precise evaluation of what I have wanted to do, or of what I have been able to do within my possibilities.

Marina Reyes Franco is an art historian and independent curator based in Buenos Aires. A co-founder and director of La Ene, she has curated exhibitions focused on contemporary Latin American art in Puerto Rico, Argentina, Colombia, Brazil and the U.S. She has contributed to various publications, such as Vice, Adelante, Mama Lince, Ramona and Beta Local newspaper, among others. She is currently working on the book Born Wild about Gala Berger’s work.