« Features

Vitreous Humor, or Abstraction Fleshed Out

Since its inception 100 years ago, Abstraction in painting has gone from art world provocateur to art market darling. Today, when much abstract painting seems to want only to please the eye, who are the artists redefining the language of abstraction and from where are they drawing their inspiration? The following essay answers these questions by contextualizing the work of three different artists sitting on the cutting edge.

By Pedro Barbeito & Patricia Felisa Barbeito

Near the beginning of Luis Buñuel’s early surrealist film Un Chien Andalou (1929), a woman stares impassively into the camera as a male hand holds open one of her eyes. A razor suddenly slices through her eyeball, and the scene cuts away just as gooey, viscous matter, the eye’s vitreous humor, spills out. It’s a legendary scene that aptly illustrates the main conceptual underpinnings of abstraction in painting: the desire to do away with overly conventionalized and therefore passive ways of seeing in order to resurrect them in a more immediate, organic, and engaged form. Throughout the twentieth-century, the best forms of abstraction recognized the broadly progressive political impact of their formal experimentations. Responding to a questionnaire about the end of Expressionism in the 1920s, Kandinsky stated that the coming period in painting would “bring: freedom from conventionalism, narrowness and hate, enrichment of sensitivity and vitality…. Realism will serve abstraction.” While the utopian aspects of this prediction obviously did not come to pass, Kandinsky’s vision of the eventual intersection of realism and abstraction rings very true in a world where the “real” has become increasingly complex, technologically mediated, and shaped by the influence of global corporate capital.

ABSTRACTION AND COMMODITY

Now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, abstract painting has nowhere near the impact of a razor slicing through an eyeball; it has become, instead, a type of visual muzak, like those Monet posters hanging on every college dorm wall: pretty, mass-produced, a soothing sign of taste, culture, and participation in the consumerist dream. Objectified into the ultimate luxury good, much abstract painting establishes its market value by sampling arbitrarily from different abstract vocabularies and historical periods in an often highly formulaic and easily reproducible way. Whether a craven catering to market demand or a knowing postmodern commentary that straddles the often all-too-thin line between critique and celebration, this work simply repeats and reinstates the cultural power and logic of late capitalism (to borrow Fredric Jameson’s apt phrase). The built-in critique of commodity status is, in fact, what seals the work’s commodity status: the double frisson of consumption and/as knowingness. Some of the most well-known contemporary abstract painting calls attention to this impasse with varying degrees of critical distance and humor. Damien Hirst’s almost identical abstract dot paintings, for example, made by the thousands by his assistants and invariably selling for six figures, attest to the artist’s identification as “brand”-it doesn’t matter what the painting is about as long as it’s a “Hirst.” Mary Heilmann’s painting/furniture installations (which often pair tastefully colorful abstract paintings with armchairs, for example), wryly link painting to interior decorating with gleefully exuberant arrangements of color and form that seem to refer, with childlike innocence, only to the hermetic pleasures of their own making and consumption. Guillermo Kuitca’s recent series of paintings return to certain monumentalized forms of abstraction-Cubism, Fontana’s slashed canvases-to call into question, in a manner similar to Magritte’s ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe,’ the status of what we are seeing. If Magritte was pointing to the difference between a real pipe, which you can fill with tobacco and smoke, and its painted image, Kuitca points to the distance between abstraction as vital gesture and commodified style: abstraction has become representation.

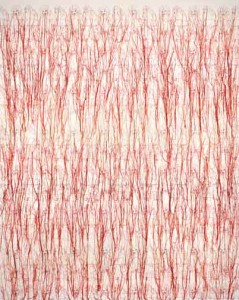

Ghada Amer, Heather's Degrade, 2006, embroidery and gel medium on canvas, 78” x 62.” Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

NEW DIRECTIONS IN ABSTRACTION

The most interesting contemporary work in abstraction recognizes abstraction’s commodity status but is not circumscribed by it; it returns, instead, to the utopian impulse articulated above by Kandinsky by continuing to enrich abstraction’s “sensitivity and vitality” in ways that underscore its politics, historical specificity, and cultural relevance. This work grows out of three main sources: the identity politics of the 60s and 70s and the focus on race, gender, and sexuality as products/constructs; the influence of new technologies-most notably the internet and digital imaging-on the language of painting; and the radically anti-institutional and absurdist impulse captured by a generation of post-WWII German artists. Occupying a literal and figurative crossroads by situating itself (messily) among media and different visual languages (including, most broadly, the abstract and representational) this work is also deeply informed by the contradictions and tensions of globalization, from celebrations of the “democratic” flow of information facilitated by the world-wide-web to critiques of the economic hierarchies and cultural hegemony it relies on and strengthens.

IDENTITY POLITICS: EXPLORING BOUNDARIES OF SELF AND NATION

Ghada Amer, an Egyptian-born multi-media artist who currently lives in New York City, is one of a cohort of artists-including Ellen Gallagher, Mark Bradford, and Trenton Doyle Hancock-who embed an examination of the discourses of identity in their formal experimentations. Following boldly in the steps of artists like Joan Snyder and Judy Chicago (who “invaded” abstract painting by putting it in dialogue with the “feminine” arts of needlework, home decoration, and hygiene, etc.), her canvases combine stitching, hanging threads, and intricate embroidery with equally intricate drawings and bold swathes of paint. There is a consistent focus on imagery of the female body-women as spectacle, exposed, on display, engaging in lonely acts of autoeroticism-culled from a variety of different sources: Disney cartoons, magazine images, etc. From a distance of ten feet, they look like Ab-Ex paintings of the 1940s and 50s; it’s only when one nears the canvases that their imagery (and their abject corporeality) becomes recognizable: the threads and paint that look like hair or washes of blood. These searingly beautiful yet simultaneously horrifying “paintings” thus present us with a dialectics of presence/absence, concealment/revelation, the objectification of distance and the intimacy of proximity, that directly link certain forms of representation and art to the marginalization of both women and Arab cultures. Yet this is a dialectics that does not resolve in any predictable way, but instead privileges the process of movement, the conceptual gap, among the possible readings that are most clearly centered on the gender identity, ethnic allegiances, and general status not only of the women depicted and the artist, but also, perhaps most importantly, the viewer him- or herself. Are these images objectifying or empowering? For whom? What kinds of pleasures/perceptions of beauty do we derive from these images and why? Is Amer repudiating her Arab background or celebrating it? Do we read the repeated use of thread in her work as a reference to the burka, to veils, to women’s “costume” in general, to shredded canvases or screens? Ultimately, her work draws out the inherent inconsistencies, knee-jerk assumptions and blind spots in the multiplicity of ways of seeing referenced. Amer thus calls attention to the pitfalls of participation in a global art market that privileges and marginalizes certain experiences and perspectives. In interacting with Amer’s work, which resists bestowing on us the illusion of a superior insight, understanding, and domination, the viewer is put in the position of having to examine his or her own most naturalized preconceptions.

Joan Snyder, Woman/Child,1972, oil, acrylic, sparkle paint and spray enamel on canvas, 72” x 108.” Courtesy of the artist.

LOGICAL SYSTEMS, PIXELS, AND MUTANT FUNGUS

The dynamics of domination and consumption have been integral to one of the most direct influences on abstraction today, the new technologies that have served as catalysts for a redefinition of the visual language and processes of painting. In the 60s, artists such as Sol Lewitt, Alfred Jensen, and Mel Bochner escaped the confines of abstract expressionism’s focus on the subjectivity of hand-made expressive brushstrokes by interrupting the direct movement of idea to canvas through the adoption of a number of mediating and structuring systems that sought to bestow a new objectivity to the making of an artwork (from the use of predetermined mathematical equations to color grids, etc.). Perhaps one of the most well-known instances of this mediation is Sol Lewitt’s famous use of the fax machine to instruct his assistants overseas on how to make the paintings for his gallery show. The work was made and installed by the assistants, and Lewitt, in a gesture that underscored his identification of art as concept (”the idea becomes a machine that makes the art,” he once wrote), didn’t go to the opening. In the 90s, the home computer and programs such as Photoshop allowed, in a related fashion, for an even greater “objective” mediation of the image by the machine, while providing the added benefit of a new digital visual aesthetic. Albert Oehlen, for example, began using software programs to create drawings that he would then print out on canvas. The lines drawn on the monitor, once enlarged and printed on large canvases, would break down into pixels. More recently, Wayde Guyton repeatedly ran canvases through a digital pigment printer to create rich, black, minimalist textured surfaces. In both cases, the resulting abstraction is very much a by-product of computer mediation and its impact on the painting process. Fabian Marcaccio, like Lewitt and Oehlen, relies on the computer as mediating system to create complex visual worlds, but in his work the mediating system does not provide a straight route to “objectivity,” nor does it help maintain the purity of art as concept. Instead, Marcaccio’s work seems to consistently point to the dangers of the symbiosis of paint and technology in that the mediations of technology threaten, at any moment, like a horror-movie zombie, to take over and turn painting over to its own greedy, self-perpetuating dictates.

Fabian Marcaccio, Re-sketching Democracy, 2004, pigment inks, oil, acrylic, silicone, and polymer on vinyl and wooden structure, 96 ¾’ x 11.’ Originally installed at Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, and Domus Artium 2002 in Salamanca. Courtesy of the artist.

In his more than 20 years of work, Marcaccio has created a “breed” of mutant paintings, called “Paintants,” that, in his own words, “force abstraction to do impossible things.” This forcing of the impossible bespeaks the carnivalesque violence that pervades his work and hovers dangerously and grotesquely between horror and a perverse, sickening glee, akin to the feelings aroused at the witnessing of a traffic accident (a phrase that, indicatively, he has used to describe the making of his work). The excessive way in which he wields his materials (paint, industrial materials, new technologies) literally has them pouring out of the canvas, demolishing the surface of representation, exposing its skeletons, its limits, and moving, like a mutant fungus, beyond them. This impossible, head-on confrontation between abstraction and technology references the impossible, sickening contradictions of our particular historical and cultural moment: the exposure of war and violence as consumable commodities, the confrontation of excessive consumption and total deprivation, the co-existence of a privileged complacency and hysterical fear. Ultimately, Marcaccio’s work turns Lewitt’s formulation on its head: now it is the machine that has become (and completely co-opted) the idea so that we are caught in its inexorable logic.

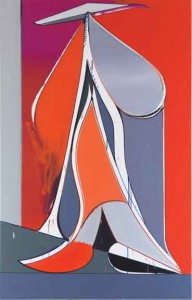

Thomas Scheibitz, Schwester, 2008, oil, vinyl, pigment marker on canvas, 98 ½” x 63.” Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

POST-WAR GERMAN PERSPECTIVES

Thomas Scheibitz eschews the mediation of computers in favor of re-establishing the greatest “possible independence” in his translation of visual information. Scheibitz and his contemporaries, Jonathan Meese, Tal R and Daniel Richter are the most recent generation in a tradition of German art (following on the heels of artists such as Martin Kippenberger, Jorg Immendorff, and Albert Oehlen) that grew out of the tensions shaping post-WWII German culture. This period saw the emergence of a visual culture-shaped by artists like Joseph Beuys, A.R Penck, Sigmar Polke, and Gerhard Richter-with a sharp political edge aimed at satirizing all political certainties and “isms.” Richter’s squeegee paintings perfectly illustrate this post-war attitude: it is only by an act of ritual destruction-metaphorized in the repeated pulling of a squeegee back and forth through wet paint-that beauty and a new beginning can occur. Polke responded by creating paintings that exposed their skeletons-using transparent fabrics that revealed the stretcher bars-as if to do away with the illusion of surface and “objective” narrative, and used images culled from a range of art historical and popular culture sources to reference human inability to stop repeating history. Thomas Scheibitz’s work, in contrast to the emphatic, theatrical irreverence and absurdity of much of the work of this tradition seems, at first glance, comfortingly familiar, abstraction at its most traditional (a sense that is reinforced by his refusal of the computer). Scheibitz arrives at his paintings through an obsessive, highly personal practice of cataloguing visual/verbal/aural stimuli that literally map his trajectory through time and space in all its predictable patterns and infinite variations. (The computer is therefore present in his work as a visual reference-evident in the hardness of some of the imagery and the flatness of some of the colors-but not as a mediator in the process). This archive provides him with a source of information that he “translates” into the formal building blocks of his work, creating a visual world that is poignantly quixotic in its anarchic insistence on the legitimacy of the idiosyncratic, personal, non-hierarchical vision; on the role of unforeseen “combinations;” on the constant dialogue and exchange-the continuities and discontinuities-between the public and the private. In a world where abstraction has been objectified into commodity, his paintings are marked by the establishment of a visual system that is radically, absurdly anti-systemic. “Lacks and excess/radicality of content is a question of form,” (Ermacora 3) is a handwritten comment Scheibitz left on an otherwise untitled printed graphic work of his. It is a comment that seems to encapsulate the spirit of his work in general, structured as it is by both a surfeit of information and a lack of system, and an identification of abstraction as our most immediate path into social reality.

In an interview with Hans Obrist, Scheibitz responds to a question about the role of utopia in his work by saying:

” I think it could almost be said that the field of utopia has diminished somewhat, perhaps because more and more can now be achieved with technology. A computer can process an idea almost like a magic wand. Today there are so many possible ways of realising every structure, including the most intangible or non-static, and of materialising it in some form or other. This becomes increasingly appealing the further you look into and seek forms. From a socio-political perspective, on the other hand, it is perhaps more the case that utopia is on the retreat. Already everything has become very realistic. Fewer risks are being taken, and it seems to me that there is much less enthusiasm for that sort of thing.” (8)

Be that as it may, the work of the three artists discussed above insists on risk-taking. Acutely aware of both the dictates of the art market and the prevailing discourses of abstraction-be they shaped by identity politics, absurdist subversion, or technological mediation-their work consistently moves beyond the sum of these constitutive parts. It thus continues to breathe new life and vitality into abstraction as a way of seeing.

WORKS CITED

- “Conversation withHans-Ulrich Obrist.” Thomas Scheibitz. About 90 Elements /TOD IM DSCHUNGEL. Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2008.

- Ermacora, Beate. A Disordered Space / Der ungefegte Raum. Cologne: Buchhandlung Walther König GmbH & Co.KG, 2010.

Patricia Felisa Barbeito is Associate Professor of American Literatures and Head of the English Department at the Rhode Island School of Design. With a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from Harvard University, her work examines the intersection of race, gender, and protest politics in a range of literary and visual cultures.

Pedro Barbeito is a visual artist living in Brooklyn, NY. His works have been exhibited internationally, including The Museum of Modern Art in Arnhem, The Whitechapel Gallery in London, The Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Connecticut, and the Museo Rufino Tamayo in Mexico City, among other venues.