« Features

Surveyor. An Interview with Xaviera Simmons

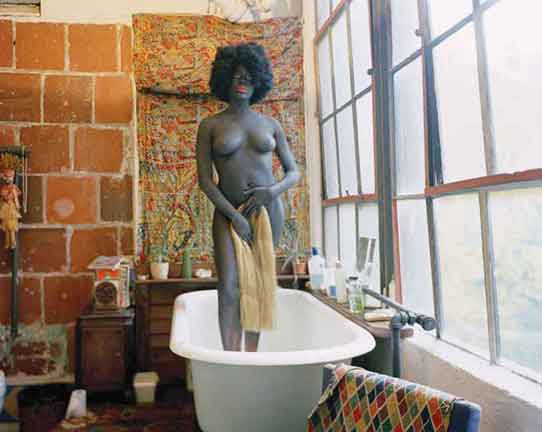

Xaviera Simmons, Landscape (2 Women), color photograph, 2007. All images are courtesy of the artist, Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery and David Castillo Gallery.

Xaviera Simmons creates photographs, installations and multimedia works that use landscape as a base on which to layer complicated characters and open-ended, non-linear narratives. Using an amalgamation of histories and memories as communicated over time through text and images, Simmons creates new characters that depart from and engage with the histories locked within landscape that are free to reference, react to, ignore or enhance them. She keenly creates stagings that are not bound by any one history or group but rather represent a synthesis of her own influences and interests and how they relate to the history of art and the American landscape. In this way, her works collapse time and simultaneously create new questions and break old notions without being preoccupied with doing so. They examine a new kind of sublime-one that is in flux, like the characters that inhabit them.

By Cara Despain

Cara Despain - Some of the characters that are placed within the landscapes in your photographs relate to early exploration and documentation (both geographical and artistic) of the American West, which can also be interpreted to relate back to expansionism and Manifest Destiny. Can you talk a little about using this ideal, in addition to that of the sublime and the ideals of the Hudson River School (which you note as a reference point), as a starting point to layer your alternate and staged suggestive narratives onto?

Xaviera Simmons - For me the landscape, the early explorations of cultural migration, migratory histories and the layering of histories; be they political, societal, art historical or using other ways to interpret concepts of history. I see the landscape at this point as both the most fertile and the most basic ground to overlay the characters that come to me when I engage with these environments. I am forever romanced by the artist’s fascination with the landscape as a topic to explore in painting, sculpture, film photography, text, dance, etc. It’s almost primal, in a way, to begin with the landscape. For so long, until the explosion of the Internet, landscape paintings-then films and National Geographic Magazine and encyclopedias-were the way “everyman/everywoman” in America entered into a relationship with art viewing and art making, I believe.

Historical landscape painting is one of the foundations of any art history curriculum, and practically everyone I know has some relationship to ‘the landscape.’ I’m interested in the layering of diverse narratives and in the ways characters can be developed when you complicate a narrative of any given landscape. I think engaging with the sublime is just one way I am working, but I think that is shifting. I am looking now at the sublime as a catalyst to explore other topics found in the idyllic, or rather the notion of the idyllic. The idyllic, the sublime, they are just one complicated way for me to enter into a dialogue with the landscape. Also, the characters that come into the landscapes I engage in are just in direct conversation to the characters I have often missed when viewing the textbook narratives of the West, the Hudson River School and the sublime. I’m interested in populating the landscapes I engage with different types of characters, characters in conflict with or in harmony with the landscape, and I’ve said this before but it bears repeating: I am really intrigued by the diverse narratives that come out of a nation of migrants. I’m American, and being American I feel at fortunate liberty to be in conversation with all of the narratives that make up the inhabitants of the land here, so to that end I feel free to choose, mix and converse with the diverse stories that are populating these spaces now. In a way, all of the histories involving migration, past or present and future, feel up for grabs and a part of the overall narrative that has been layered upon us historically through image and text.

C.D. - How did your walking pilgrimage tracing the trans-Atlantic slave trade affect or become a part of your artistic practice? There is an evident tie thematically to your work in African-American history, migration and the surveying of landscape(s). Also, the slave trade relates to early notions of land ownership and expansionism that are inevitably tied to the American landscape. Is this something you are directly engaging with in the photos, or does it more so provide a historic base to use as a springboard?

X.S. - Walking and hitchhiking for two years (one-plus years of which was with a group of Buddhist Monks and lay people in walking meditation and communal living) has certainly provided me with an amazingly rich relationship to these diverse ideas and histories and to the landscape as a whole narrative, the landscape as a whole topic, which is pretty vast. I have to catch up to myself with my thoughts on it.

At this point I see that walking pilgrimage as an engagement with diverse histories and narratives, and at one point it provided a historic base for my works, but now I think my works are in another place of referencing. I’m in conversation with my peers and then with a diverse cross section of artists, both historical and present, and their working methodologies. I never want to take all I can from any one source of history. I want to leave room for different histories to still have a personal relationship for me, and that can not happen if I try to deplete one group’s narrative. At this point I feel free to be in direct conversation with any topic that can fill the vessel of my practice as an artist. That might be the viewing of Inca architecture, today’s front page of the Financial Times, images of the copper mining operations in the Congo, a stack of industrial design magazines or the lines on a Rick Owens jacket. There aren’t too many things that cross my path that I do not try to engage with in my work. I’m trying to catch up with my own inspiration-I’m grateful for that.

C.D. - Can you talk briefly about your experience in the actor training program at the Maggie Flanigan Studio? It seems to have provided you with distance that allows you to divorce yourself from the characters you create in your photographs. Was this something you did to deepen your practice? You mentioned that it is important that they are characters inhabiting a place and not portraits of the maker.

X.S. - Oh boy, that’s actually a big one for me. I absolutely loved working with Maggie and the actors she works with in her school. Maggie is the best and a tough teacher. I feel like in the two years that I studied with Maggie I only touched the surface of what it means to be a great actor. I have such a respect for the craft, for the ability of someone to use their body as an instrument, to be able to work with themselves and their emotions and have an impact on others. That’s the work of a great actor and director. Maggie really teaches [people] to have an appreciation for the craft of an actor, to treat it as if you are a technician and to work clearly and fully. To take risks…I think the biggest lesson I bring to my studio from working with Maggie is preparation. An actor really does prepare, and an actor comes and has trained herself to come prepared with the necessary tools to get a job done. That’s what I keep coming back to from my training. I never intended to audition for traditional roles or anything like this when I studied with Maggie. It was always with the intention to fortify my own photographic, performative, installation and sculptural works. I bet if you spoke to her she would say I barely grasped what she was teaching, and out of respect for her, I would agree. There is just so much to learn from a teacher like Maggie, and two years is certainly not enough time to really have learned those lessons. Great actors, like all great craftspeople, are technicians who work on their craft and take it very seriously, knowing the ins and outs of what they are doing…It’s a lifelong quest.

C.D. - Much of your work concerning landscape plays not only on historical/art-historical references or tropes, but also on a certain vernacular that seems to simultaneously represent the past and present-the hand-painted signs on found wood, the non-period-specific clothing and settings, and the intrinsic quality of the landscape leaves the works feeling open-ended. Is there a balance there that you are intentionally finessing? Are the images meant to function as both photographs and acts or moments that are documented? Is it important that they are often timeless?

X.S. - I really am engaged with in-between spaces, with nonlinear narratives, with narratives that drop off and then continue, with shifting landscapes and shifting narratives, shifting characters and shifting histories…I don’t see an illusion of time, I just see the amalgamation of all of the histories and narratives and my own interests.

C.D. - There is a balance of reality and fiction in your work-the fictive stagings reference real histories, and the characters recontextualize or alter these histories. Though these aren‘t self-portraits, and it is important that you are in the photos as a character, is the fact that you yourself represent an alternative to the historically white male lineage of landscape photographers/painters/explorers/landowners a tool in subverting the histories implicated in your images?

X.S. - None of my works are self-portraits, these are explorations of characters in relationship to landscape and other themes mentioned above. I am electrically inspired, meaning the inspiration is steady and constant and to that end I am constantly trying to keep up with myself and what I engage with. Literature, news, music, design, conversations, colors, textures, forms, science, midwifery, travel, it’s all just fertilizer for the works. The conversations I have in my studio with art-historical references and in relationship to my peers and their various practices are what I am really addressing and engaging with.

C.D. - How do you choose or ‘find‘ the scenes or landscapes you use as the setting or backdrop in the photographs? Some of the works have specific or implied historical import, while others sort of function as almost generic landscapes of different types (Western, pastoral, etc.). What research goes into choosing where you shoot?

X.S. - I work with large-format film cameras. I read a sentence and that can send me into a tailspin with work. I am constantly taking notes and sketching. My images are always sketched out beforehand. I know the landscapes I want to engage with and I know the references I am interested [in], but I let them get convoluted purposely at times, meaning I can only prepare and research so much, and then the moment of action has to happen. I come prepared to develop a character, to evoke a certain feeling in the works, but in the moment of making a work, the gestures and movements in an image come from the moment and may change or shift my original intentions, even if slightly. That’s also part of the joy I have still working with analog film-I still am surprised when an image is processed, when I see a negative and know that I have something to work with, when I realize the preparation and process I put into the works has shown through.

C.D. - You shot some photographs recently in Utah-a historically charged territory preoccupied in many different ways with land, migration and ownership. The history of landscape within art here also carries its own special brand of iconicism and the sublime. Can you discuss your experience and intentions with the project at the UMFA and with the landscape in Utah?

X.S. - I actually made works all over the West a year or so before the show at the UMFA, and so those images were not specifically for the project at the UMFA, they were born out of my own interests in the Western landscape and the specific iconicism of that territory. Working in the West as a Northerner feels like being on another planet. The landscape is just so vast, the history so foreign and the culture quite different, and I find it extremely diverse in a new way, as compared to the Eastern portion of the states. The sublime feeling of the West is a far more present or rather is a current-time sublime than that of the East. I think historical paintings and photographs of the East Coast have such a close kinship to historical European and American paintings, where as in the West, that landscape is fresh and not as mined, at least when viewing it from an art historical perspective. I’m always intending to view the environments that I engage in with both fresh eyes and eyes that have some seasoning, because I’ve engaged these spaces via films, images or in texts. I think we all have a certain memory and expectation of specific landscapes, and I hope that in my works I am working in and out of those memories. I hope that I am constructing new ways of viewing these spaces vis-à-vis the characters and their relationships to these environments. I think even when I am working with clear intention and vision within my works, there is a lot of room for a continuing questioning process. I cannot say that I have all of the answers in my own works-there are constantly questions that keep coming as a result of the work that I make.

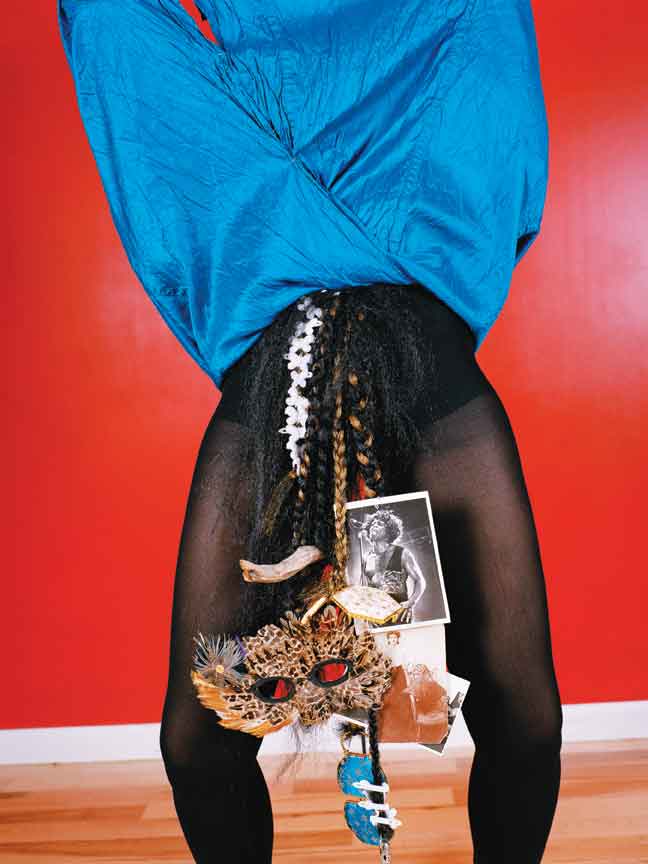

C. D. - Some of your other works employ the body in a different, more object-based, way and lack a landscape in the traditional sense but often have environments that are implied by the staging (such as Landscape (2 women) and Beyond the Canon of Landscape). These pieces feel more direct and overt in their referential objects. Can you discuss these photos? They also seem to reference costuming and tradition more heavily.

X.S. - Landscape (2 Women) directly references landscape-it’s just landscape in the urban sense, it’s the possibilities of spontaneity and play that are at work in this image. I’m interested in the performative in this work, and I’ve always worked out of doors, and out of doors encompasses much more than the sublime. The urban is rich with possibilities, but my exploration in it feels different because there isn’t this overwhelming, overarching sublime landscape in these works. These works force the characters into center stage, much more than the traditional landscape-based works. I believe the spaces may be different, but the intuitions are the same.

I think the biggest shifts for me are happening now. I produced Beyond The Canon of Landscape to get myself into the studio away from the out of doors. I made that work in 2007 and only made one like it, and it’s taken me three years to go back to that topic and expand on it. And that’s what I am doing now. I’ve always wanted to return back to this project and expand on it, and it’s been through a new series of works called Index/Composition. These works are really looking at sculpture and how the sculptural can be contended with in the photographic and how the photographic can be contended within the sculptural. There is an entire new dialogue I am having with the sculptural, with taking things off of the wall, with working with wood and other materials besides the photographic and the installation. So, for me, the index series, of which Beyond The Canon was the first, is my reaching out to the sculptural in the photographic. These works are about a layering effect of the sculptural, the collage and the photographic. And the large-scale, text-based wooden sculptural installations like On Balmy Terrain, which is on view at the UMFA, are doing the inverse. These works, among other things, are looking at the materials of the sculptural to engage the photographic and the cinematic. I see these sculptural installations as landscapes, just as the landscapes are portrayed in the photographic images.

C.D. - What other projects and exhibitions do you have upcoming for 2012? Will you be continuing these same investigations?

X.S. - I have a solo presentation of photographs and sculptures at ADAA with the Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery in March, my vinyl record project Thundersnow Road and its installation will be on view at the Miami Art Museum. I have the culmination of my artist residency at The Studio Museum In Harlem, a solo show of community-based photographs produced in conjunction with More Art and the Hudson Guild in Chelsea will be on view through April, and I’ll be traveling to Sri Lanka this summer to work with an artist collective in Colombo in consort with the U.S. State Department and The Bronx Museum’s SmART Power Initiative. And I’ll be performing in conjunction with the finale of Clifford Owens’ great project Anthology at MoMA PS1.

I sketch everyday, and I am always looking at the works of my peers and colleagues to be in conversation with, and so I’m really trying to take some time to see what I have been sketching this past year to understand how to take my works in new directions. Upcoming in 2012 I will become a better sculptor and I will be reading more newspapers so that I can make works that respond to the movements of the contemporary world in a more direct way. I’ve been collecting new images, found images that I manipulate similarly to the project I showed at MoMA PS1 titled Superunknown. This time I’m looking at the sublime or the inverse of the sublime when a sizable mark is forced on the land and is man-made. I’m looking at images where the landscape is penetrated and manipulated directly through man’s hands and the awe of viewing that engagement through images. Mostly right now I am looking at images of various types of mining.