« Features

A Grey Dawn: On ‘The Problem of God’

It is fitting that Düsseldorf, the city so formative in the life of art shaman Joseph Beuys, would host an exhibition investigating such themes as anthroposophy, bodily suffering, performance, ritual and social philosophy in contemporary art. Rather than attempting to be a shamanistic spirit guide in shaping society, politics or faith, “The Problem of God” traces and reveals connections and contradictions that exist within these realms. Regardless of intention, however, it is still possible for the viewer to experience personal spiritual revelation amidst a displaced Christian iconographic lexicon perforating the boundaries between heaven and hell through charged imagery that for many still hold powerful agency.

Thirty-three juggernaut artists from around the globe showcased 120 works of art from September 2015 through January 2016. The Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen organized the exhibition at the historic K21 Ständehaus in Dusseldorf. I was fortunate to experience the collection in person in late December, just before Christmas. The exhibition included lectures, panel discussions, special guest tours and a 400-page catalogue printed in both German and English, with essays addressing the function of Christian imagery in contemporary art.1

According to Marion Ackermann, the director of the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, the function is significant: “In contemporary art, a preoccupation with Christian symbolism plays an important role,”2 she said. “Both art and religion offer us access to experiences that touch on the very essence of what it means to be human, reaching beyond the merely representational or cognitive to the emotional sphere. They are also both strongly associated with notions like the material and the spiritual, with image production and image worship, and with transcendence, the realm beyond ‘physical’ experience. The imagery that emerged from Christian religion forms part of our shared visual and verbal memory, so it is only natural that contemporary artists should make use of its complex possibilities as a sort of grammar for their works in highly diverse ways.”3

Michaël Borremans, The Bread, 2012, video still. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerpen. © Michaël Borremanns. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung NRW.

The visual grammar of this exhibition models the work of Aby Warburg (1866-1929). A cultural scientist and art historian, Warburg explored universal visual patterns and their shifts in meaning through temporal and contextual changes. He collected images and grouped them together on panels to illustrate the evolution.4 This created an image bank, his “Mnemosyne Atlas” or Atlas of Images. “The Problem of God” includes 10 replications of his “Religious Iconography” boards. Displayed on the second floor of the museum were enlarged black-and-white prints depicting Warburg’s pseudoscientific, salon-style pinning of photographs. Mounted on black felt boards, the photographs and prints depicted religious paintings and sculptural imagery. Curator Dr. Isabelle Malz applies this open-ended framework across three levels of the Ständehaus. She writes in the catalogue, “The legacy of Christian imagery and cultural practices, which-detached from its religious context-has flowed into secular life, proves to be as enduring, complex, and paradoxical a reference system in art as it ever was. The religious motifs and themes addressed in these works of art have long since become independent of their original functions; indeed they have continued to develop and have taken on new, different levels of meaning. Nevertheless, aspects of their original substance remain untouched. As vehicles of the afterlife, pictures and images are nothing other than montages of heterogeneous meanings and times. If one considers this statement by Georges Didi-Huberman in conjunction with Aby Warburg’s concept of images as time-specific yet anachronistically timeless evidence of a visual legacy, then these different level-as they emerge in the works of art in this exhibition-give rise to fascinating configurations and inter-connections that reflect some of the most pressing questions and topics of the present day.”5

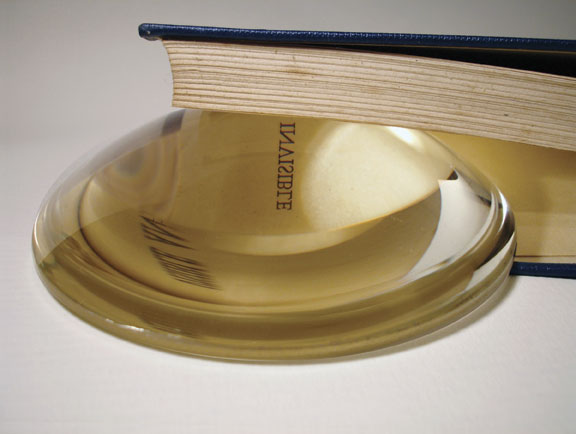

Pavel Büchler, The Problem of God, 2007, found book and magnifier, 7 7/8” × 10 5/8 × 1 31/32.” Private collection Bern, © Pavel Büchler. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung NRW.

While I do agree that Christian religious motifs and themes have taken on new and different levels of meaning, I’m not certain of their independence from original function in their essence. That is to say, the contexts of these themes may have changed, but I’m not convinced the transactions between religious motifs and those who witnessed them in the halls of K21 are all that different on a fundamental level. The transcendental qualities inherent in these kinds of images are what make them so compelling for artists to pick up and use in the first place. The exhibition does indeed give rise to some of the most pressing questions of our day, but this is made possible by addressing ancient ones.

“The Problem of God” wrestles with our visual representations of divinity but may be read as a problem that God has: How does a being that cannot be fully represented function or operate in human visual realms? Pavel Büchler contemplates the use of reflection as a possible conduit for the divine. In a work from which the exhibition draws its name, Büchler cleverly inserts curved glass into a closed book. The glass separates the pages, creating a wedge. From a specific angle, the word “invisible” appears in the glass. For many Christians, the Word of God itself, first spoken, then written, is God. Text, as a form of image, makes the invisible visible through a lens, via refracted and reflected light.

A second strategy toward divine representation draws connections to God and human suffering. In the Bible, the book of John indicates that the, “Word was made flesh,”6 and it was a poetic path through renderings of flesh, and more specifically, images of bodily suffering, one needed to pass through to see the lower level of the exhibition where Büchler’s book and glass piece was located. To get there, one must traverse a katabasis of sorts, a descent into the spirit world by way of the flesh. The subterranean level of the Ständehaus contains an astute selection and arrangement of sobering works that dare visitors to forget the realities of mortality. In a provocative move of foreshadowing, curator Dr. Isabelle Malz has placed Kris Martin’s For Whom (2012), a large steel bell, suspended above the steps by a steel beam leading to the basement. Both beam and bell have a beautiful weathered green patina, and the beam handles both the physical and metaphorical weight of the title. In a reference to John Donne’s Meditation XVII, Martin has removed the clapper from this bell. The bell was timed to swing on the hour, but because of Martin’s alteration could only ring in the minds, and not the ears, of those who pass under. Through the physical absence of sound, a richer presence resonates, thus exploring memory by twisting narratives toward a heightened awareness.

Berlinde de Bruyckere, Schmerzensmann IV (Man of Sorrows IV), 2006, wax, iron, epoxy, 13’ 7.38” x 3’ 4.15” x 3’ 2.58”. Ursula Hauser Collection, Switzerland. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. © Berlinde De Bruyckere. Photo: Mirjam Devriendt. Photo courtesy of Kunstsammlung NRW.

Near the bottom of the staircase, a small, dead animal draped over a worktable, legs dangling, arrested my vision. I paused for a moment, wondering what motivated my intense curiosity to desire a closer look. Through closer examination I learned it was in fact a young horse prepared by taxidermy, a work presented by artist Berlinde De Bruyckere’s Lost III (2011). The animal, exquisitely beautiful with rich dark tones of velvet brown and black, filled the room with its absence and presence. The body of the horse was certainly displaced from its original context, yet its spirit permeated the space. My gaze drifted upward from the table to engage De Bruyckere’s other pieces, selections from the Schmerzensmann (Man of Sorrows) series, wax and resin molds of human forms suspended from rusted poles with hefty iron bases that look like decapitated lamp posts. The drama and theater of these bodies in flux made me feel as though I was part of a reenactment of some kind, or perhaps brought to bear witness to some horrible torture or terrible reality. With each circle round the pole, we entangle ourselves with the figure, mangled and bent. Much has been written about De Bruyckere’s source material and inspirations, ranging from the crucified Christ to Flemish old masters such as Hans Memling and Rogier van der Weyden. To be sure, her work wounds. She speaks the visual language of persecution, torture, crucifixion and shame.

Kris Martin, For Whom, 2012, installation view at K21. Photo: Achim Kukulies. Courtesy of Kunstsammlung NRW.

Adjacent to the flesh-colored pigments woven throughout De Bruyckere’s wax figures, my eyes only needed to slightly shift in depth-of-field focus to see large drips and splatters of blood red run down Hermann Nitsch’s panoramic canvases titled Passions fries (1962). The crimson paint, three-in-one canvas arrangement and title evoke the Passion of Christ, amplified by the proximity of De Bruyckere’s suspended figures.

With De Bruyckere’s dead horse in the foreground, bodies hung from iron poles mid ground, and canvases sprayed with blood in the background, I needed physical and emotional escape. I quickly turned around and my eyes met Francis Bacon’s classic piece, Fragment of a Crucifixion, offering little solace. Bacon, an atheist, appropriated religious imagery to wield their emotional and transcendental powers. In this piece, a portion of the cross cuts vertically and horizontally through the canvas, a perched being sits atop the cross beam and, centered on the cross, a second grotesque figure, pinned down, mouth open and presumably naked. The weight of the beam recalls the steel beam of Martin’s; the indistinguishable masses of flesh attached to poles clearly relate to Bruyckere’s in content and form. Then, I noticed my own dim reflection in the museum glass that protects Bacon’s painting. In seeing myself I was forcibly made aware of my own context and position-a liminal space, between the painted image of the cross and to my rear the remains of a dead animal, and beyond that corporal sacs of flesh-like resin mounted to iron, set against a backdrop of blood-stained canvases.

Because one awakens to the very materials and constructions of art, however far reaching, within the context of individual perception, art at its best lifts us beyond those physical limitations, or through them, as in the case of the lower level of the Ständehaus, to transcend constraints and touch the spiritual. Standing between the flesh and blood, between cross and death, I confronted mortality and approached something beyond it. All the weight of what was positioned behind me became superimposed through glass onto the crossbeam of Bacon’s painting. For me, it was as if mortality itself were pinned there. Perhaps I saw what I wanted to see, or needed in that moment to see, but there it was nonetheless. Similar to Büchler’s curved glass inside a text, I was able to experience something beyond what I could apprehend, not despite materiality, but through it.

Katarzyna Kozyra, Looking for Jesus, 2012, video, project supported by ATLAS SZTUKI (PL), W&W A LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (DE), PASTWOWA GALERIA SZTUKI W SOPOCIE (PL), © Katarzyna Kozyra Foto: Katarzyna Szumska, Courtesy of the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation

I ascended the stairs to reorient myself and returned to Warburg’s Image Atlas. The selections focused on religious imagery, and I hovered in and out of the museum arcades and hallways considering the contemporary collection of images under the same theme. Although it was Michael Borreman’s video piece that drew my attention to the exhibition, originally through the marketing material and his critique of the liturgical practice of communion, it was two other nearby video works that sustained my interest. Inspired by a section of a Hieronymus Bosch painting depicting a quartet of executioners surrounding Christ, Bill Viola’s The Quintet of the Astonished (2000) brilliantly explores the complexity and range of human emotion in crisp, hyper-slow motion. Viola’s figures, lit with luxurious chiaroscuro, evoke the evolution and nuance of emotions. In this context, the work is as relevant as anything in the last year.

In Aernout Mik’s silent video piece Speaking in Tongues (2013), a two-channel rear projection work, positioned on the ground and hitting awkwardly about waist high were two adjacent screens. The surreal interactions between professionally dressed men and women engaged in emotional, physical and possibly spiritual exuberance countered the transfixed group of viewers that stood with me in front of the piece. Shot in slightly slowed down speed and from a hovering, levitated perspective, its hypnotic gravitation, through physical and physiological cues, unveils its content. The actions slowly morph from mild-mannered, New Age corporate exercises to evangelical, charismatic convulsions and dramatic embodiments of spirit. The blurred lines create purposeful discomfort. Mik’s piece is not a complete condemnation of the sacred. Because it refers to the spiritual practice of glossolalia, within a silent context, Mik condemns actions by those who misuse the practices and rituals toward manipulation and abuse, thereby positioning those actions as blasphemous. The juxtaposition and blending of corporate and religious call out both organizations on the potential for misconduct. This piece is, nonetheless, a dynamic exploration of the power and complexity of human emotion and spiritual embodiment, similar yet very different in perspective to Viola’s. Aby’s method of grouping to provoke comparison and conflation proves a compelling notion within and between Viola’s and Mik’s work.

From a morgue-like descent through body, human suffering and a confrontation with mortality to subsequent ascensions to emotion and spirit, the exhibition rises even further with the work of James Turrell’s Grey Dawn (1991), part of the permanent collection at K21. A dark empty space prepares the eyes for an encounter with a void, filled with the intangible. Turrell encapsulates the spirit of “The Problem of God”: explorations of absence and presence, a void, filled with infinite ashen light. The eye plumbs an endless space but cannot quite apprehend it. Paradoxically, I simultaneously had the sensation of being engulfed by it. Turrell, a Quaker, has aimed his practice specifically at creating religious sacred spaces in the past, first for the Society of Friends Live Oak Meeting House, then again in 1986, re-creating that work in part at PS1 in Chelsea.7 He also revisited a direct religious engagement with light as recently as 2013, once more for a Quaker Meeting House in Philadelphia.8 The Quakers have a rich understanding of the connections between humans, God and light. Believing in an “inner light” that all persons have that contains the capacity to guide them toward truth, Quakers seek to orient themselves toward it in a specific way, in an effort to see it and see by it. In this way, Turrell’s work relates to Büchler’s book and glass piece. This notion also relates to Martin’s altered bell by asking those who pass under it to listen for an inner sound, one not totally imagined, nor totally physical, but remembered and thus present.

It is a rich moment for contemporary artists appropriating, critiquing and honoring Christian religious images and content. This exhibition makes evident that those images, themes and motifs are alive and well, no longer existing in the moonlit night of a so-called secular culture of art and practice, one I’m not convinced completely existed in the first place. This kind of monolithically flat label misses the complexity and nuance of “The Problem of God.” Here, contemporary artists blend and borrow Christian images as collective visual grammar and herald a grey dawn of Christian iconography, one in which the Christian lexicon is reorganized, collaged and appropriated yet retains the capacity to be radiant nonetheless by passing through the physical and material to touch the transcendental, and thus approach the spiritual.

Notes

1. Malz, Isabelle, and Marion Ackermann. “Foreword.” The Problem of God. Windelsbleicher Str. 166-170 D-33659 Bielefeld, Germany: Kerber, 2015. 306-307.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid., p. 312.

5. Ibid., p. 322.

6. Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller. “John 1:14.” The HarperCollins Study Bible: New Revised Standard Version, including the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books with Concordance. San Francisco, Cal.: HarperSanFrancisco, 2006. 1816.

7. “James Turrell: Live Oak Friends Meeting House”. ART21. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2016.

8. Chestnut Hill Skyspace. James Turrell Skyspace in Philadelphia, Penn. http://chestnuthillskyspace.org. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2016.

Jon Seals is a conceptual artist, teacher, and curator. He holds a M.A.R. from Yale Divinity School and Yale Institute of Sacred Music and a M.F.A. in Painting from Savannah College of Art and Design. His artistic practice is organized around exploring the ways in which identity relates to memory, loss, and redemption in visual culture. He is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Art and Digital Media at Olivet Nazarene University.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.