« Features

Anthropophagy of a Biennial

By Héctor Antón Castillo

Integration and resistance in the global era was the curatorial mainstay of the Tenth Havana Biennial (March 27 - April 30, 2009). What dreams do excluded victims of geographic fatalism harbor? How can we recognize a masochistic utopia (or long-lived nightmare) that conceals political demagoguery? Can a renewed outbreak of identity neuroses be appeased? Such questions can only find answers in the driveling notions (using Isidro Reguera’s term) that promoted the design of an event housed in the tenuous periphery, confined within its borders.

Further questions may be inferred that have no foundation whatsoever: What magic formula allows us to assemble local figures who are not only unknown but also lack a strategy that would allow them to gain access to hegemonic centers? (Notable is the absence of many mainstream Latin American artists who could give the Biennial exposure.) Is it not unfortunate that in visiting the ancient dungeons of the Morro-Cabaña Historic Military Complex, we recall the prisoners who once filled it? Thus, this Biennial has taught us something: the time has come for the premier art event on the island to change its venue, so that the work of the marginalized might be shown in an ambience free from past tragedies.

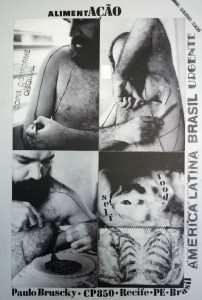

The Biennial turned out to be another political performance, matching its twenty-fifth edition to the triumphant fifty years of the Cuban Revolution. Even on the catalogue’s dedication page, we glimpsed triumphal propaganda. To illustrate said auto-celebration, there were some old cohorts among the special invitees: Luis Camnitzer, León Ferrari, Guillermo Gómez Peña and Sue Williamson. Their works were exhibited alongside the Brazilian, Paulo Bruscky and the Japanese designer, Shigeo Fukuda, who truly demonstrated their ability to reinvent themselves without abandoning the conceptual premises that define their works.

Among the group projects, a note of distinction was provided by the display of Chinese contemporary art at the former Centro Cultural de España. This exhibition of paintings allowed us to distance ourselves from the bitter taste of Third-World Latin American folklore. The rest of the Biennial shows were inundated with tons of conceptual garbage incapable of stimulating any kind of commentary.

Meanwhile, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes welcomed Corina Matamoros Tuma’s curatorship of “Resistencia y libertad” (Resistance and Liberty). It included the oeuvre of three artists emblematic of Cuban art: Wifredo Lam, Raúl Martínez and José Bedia. It appears that Bedia has once again become the favorite son of the same official institutions that launched his career as one of the fetish creators of the so-called diaspora of the nineteen-eighties. However, the show was received with some apathy, since it was all just too predictable: the well-known paintings of Lam, part of the museum collection; Raúl Martínez’ revolutionary pop; and Bedia, as always, involving the observer in his transcultural rhetoric.

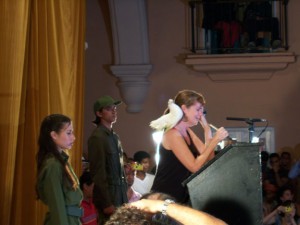

The Biennial event, which attracted the most media interest, was the performance conceived by Tania Bruguera at Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam. This artist arranged for a dais with microphones, so that anyone could take the stage and say whatever he wished to say for one minute. Surprisingly, dissonant voices expressed nonconformity despite customary totalitarian consequences. Naturally, defenders of unconditional loyalty to the revolutionary legacy also appeared (although the latter were received with a silence that neutralized the hisses and murmurs).

Such an openly provocative gesture had not been seen in Cuban art since the Juego de Pelota (Ballgame) of 1989. In effect, Tania’s performance hit a sore spot: the lack of visual production capable of tackling insular political reality in its plenitude of contrasts. So much apolitical art is created in Cuba that anything that touches on social immediacy implies propaganda. Hence, pieces such as Galería I-meil by Lázaro Saavedra and Cátedra Arte de Conducta (another piece by Tania Bruguera) can appear anachronistic owing to their excessive reality. No one disputes the fact that Tania’s performance was transformed into startling propaganda. It revealed the ubiquitous fear that limits the narrow framework for civic action available to the average citizen eager to hold an opinion.

Once again, collateral exhibitions were the most attractive. However, it should be noted that on this occasion quantity prevailed over quality. Everything appeared to respond to the Beuysian view that every man is an artist. Every square inch of corner or wall space capable of being used as a gallery was destined to hold a collection of diverse pieces and creators. The usual veterans salvaged the Biennial. There were works by René Francisco Rodríguez, Eduardo Ponjuán and Lázaro Saavedra. Internationally renowned Carlos Garaicoa presented a meticulous First-World oeuvre, displaying the “crown jewels” of western political repression using formalistic codes designed so as not to alert cultural officials.

The Biennial is like a fisherman’s net cast on the high seas. It always brings us something: a salvageable piece, the future memory of a momentous event, an exile who returns to the island after a prolonged absence, an avalanche of dubious displays in the name of fine art. The Biennial is a show that invades the city with a number of dissimilar fragments. Fortunately, in the midst of the weariness resulting from the discoursive homogeneity that tends to prevail at the premier Cuban visual arts event, something memorable can always be found in each edition. The Biennial is a spark of survival that feeds upon itself until it dies out in the blink of an eye. In conclusion, I almost feel obligated to dismiss political uproar with the urgency of a euphemism: The Biennial is never a complete success or utter failure; it cannot be judged from such a radical vantage point. Could we hope for a more pathetic end to this brief review?

Héctor Antón Castillo: Journalist and independent art critic. He resides in Havana and has collaborated with publications such as: Parachute, ArtNexus, Revista Artecubano, Gaceta de Cuba, Revista Unión, Réplica21, Salón Kritik, Esfera Pública and La Bienal de Miami.