« Features

Archive as Narration

Sharon Hayes, An Ear to the Sounds of Our History (The Essence of Americanism), 2011, vintage record covers, 24.8” x 74”. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin.

By Anne Swartz

From Hanne Darboven and Martha Rosler to Song Dong, archiving has become a way to incorporate inventories into art. In the current Information Age, we have access to more information than ever, as well as more ways to store, record and document experience than ever, which has intrigued artists and given them an increased set of tools.

Archives are different than libraries in that they are typically highly specific collections of information, usually text, but also include visual material including ephemera. George Orwell wrote in his dystopian novel 1984 about the significance of constructing historical knowledge: “He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past.” What these artists create shows a way out of the narrow view of the “official story,” promoted by any authoritarian institution or governing entity, of the past and present, in hopes that we’ll meditate on where we want the future to go.

Several women artists have used archives or archiving techniques to examine sexual identity, political content or personal and collective memories in their art, including Elise Engler, Zoe Leonard, Renée Green and Sharon Hayes. These artists, all based in New York City, use these approaches to mine and excavate previously unexamined or hidden sexual and political histories, experiences and relationships in new narrative structures of contingency, uncertainty, analepses, storytelling and dilemmas. They bring them into public spaces, including museums and galleries, to counter past and continuing reduction, or even censorship, of women’s lived experiences. Archives and archiving have enabled artists to represent and narrate the origins and continuity of women’s sexuality, politics and lives in wholly new ways. I’ll briefly survey Leonard, Green and Hayes, focusing most of my attention on Engler, whose work has not been as widely circulated as the other artists.

Zoe Leonard’s The Fae Richards Photo Archive of 1993-96 consists of 78 gelatin prints, four chromogenic prints and a notebook of seven pages of typescript on paper, made in collaboration with filmmaker Cheryl Dunye. It is an imagined visual and verbal text of an imaginary black actress (1908-73) whose 1930s film and singing career, according to the narrative, was disrupted and destroyed by racism because she resisted stereotyping. The images tell the story of a woman’s evolving identity as a lesbian and her sexual relationships with two other women. She didn’t exist, but her story merges tales of women whose lives were undocumented and unrecorded. The text has the effect of validating the images as it narrates them. The staged experience validates their experiences.

Renée Green, Partially Buried in Three Parts, 1996-1997, installation view, Secession, Vienna, 1999. Photo credit: Pez Hejduk. Courtesy of the artist and Free Agent Media.

Renée Green’s Partially Buried in Three Parts of 1996-99 is a three-part work that exists as an installation and as three videos. Her project in this work (and in her larger oeuvre) has been to consider the way media archives experience, as ways of retaining and chronicling memory and history. She combines private and public recollections to bring history to life, and her videos are intentionally “homemade” in order to convey the quality of the personal in public experience. In the first part of the work, she looks at the year 1970, examining Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed of January of that year, which consisted of a woodshed and 20 tons of dirt, alongside the killing of four students (and injuring of nine others) by National Guardsmen at Kent State University in Ohio on May 4, 1970, as well as the interweaving of her personal experience as a young child waiting for her mother to come home from a class she was taking there. May 4, 1970 was painted on Smithson’s installation after the killings, adding another layer of meaning to it beyond what Smithson had intended.

Green continued her detailed examination in the other two parts of this work. In the second part (Übertragen/Transfer), she examines the memories of 1970 via people of German descent living in the United States. As she had been splitting her time between Germany and the United States since 1991, in this work she examines what location has to do with a person’s experience of place. In the third part (Partially Buried Continued), she intersperses images she was shown of the Korean War as a child with photographs taken in Korea in 1980 and photographs taken by her later. She adds an examination of author Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, who one week after the publication of Dictee, an experimental novel about the lives of several women, was brutally raped and slain by a security guard at the Puck Building in New York where her husband was photographing. She juxtaposes outmoded technology (slide shows) alongside repeated use of image and text as a way to highlight how fragmentary our notions of the past are.

Sharon Hayes uses the archive as a way to mine historical slogans and word objects and consider how they construct our idea of ourselves through our history. She’s concerned with oral storytelling traditions and the lived experience of every day for anyone living progressively in our society. She has created archives of objects often dismissed, such as flyers and other ephemera, or outmoded technologies, such as the spoken word album, and used them as a way to engage the viewer in an experience with the political past and how it bears on the present. In An Ear to the Sounds of Our History of 2011, Hayes compiled record covers of spoken-word albums, usually political in nature, though some are quasi-political (as in the case of those by Jackie O), and combines the actual object with audio from the records. The piece began as Spoken Word DJ, a July 24, 2010, performance in conjunction with the exhibition “Haunted: Contemporary Photography/Video/ Performance” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Hayes mixed the spoken-word albums, working in front of a board affixed with many of their covers. The piece is broken up into sections of similar albums, each of which is usually named for one of the albums (as the title of the whole work is named for television journalist Eric Sevareid’s 1974 album of his notable newscasts) or for the main speaker in that grouping. The sections are: The Ballot or the Bullet, But I Am Somebody, Voices, Road to the White House, Big News, Politics USA, Recorded Voice, The Longest Day, Woman Rose, The Essence of America, Jackie O., Getting Through, A Time to Keep, The World in Sound and MLK/JFK. The collection spans the years 1948 to 1984, when political speeches were often available on vinyl records. Hayes uses the covers as markers for political events–some similar, some different-constructing a collage of recent history and popular political discourse.

In Hayes’s Join Us of 2012, made in collaboration with Angela S. Beallor, 600 flyers from the 1960s to the present are hung in a massive grid. The flyers were copied from the personal and public activist archives protest and often call on the viewer to protest the Vietnam War, the U.S. invasion of Iraq or AIDS or as come as calls to rally for gay rights marches, feminist actions and occupy activities. While activism is the reason for each of these flyers, they are grouped by the artist into a visual pattern that is intended to be aesthetic.

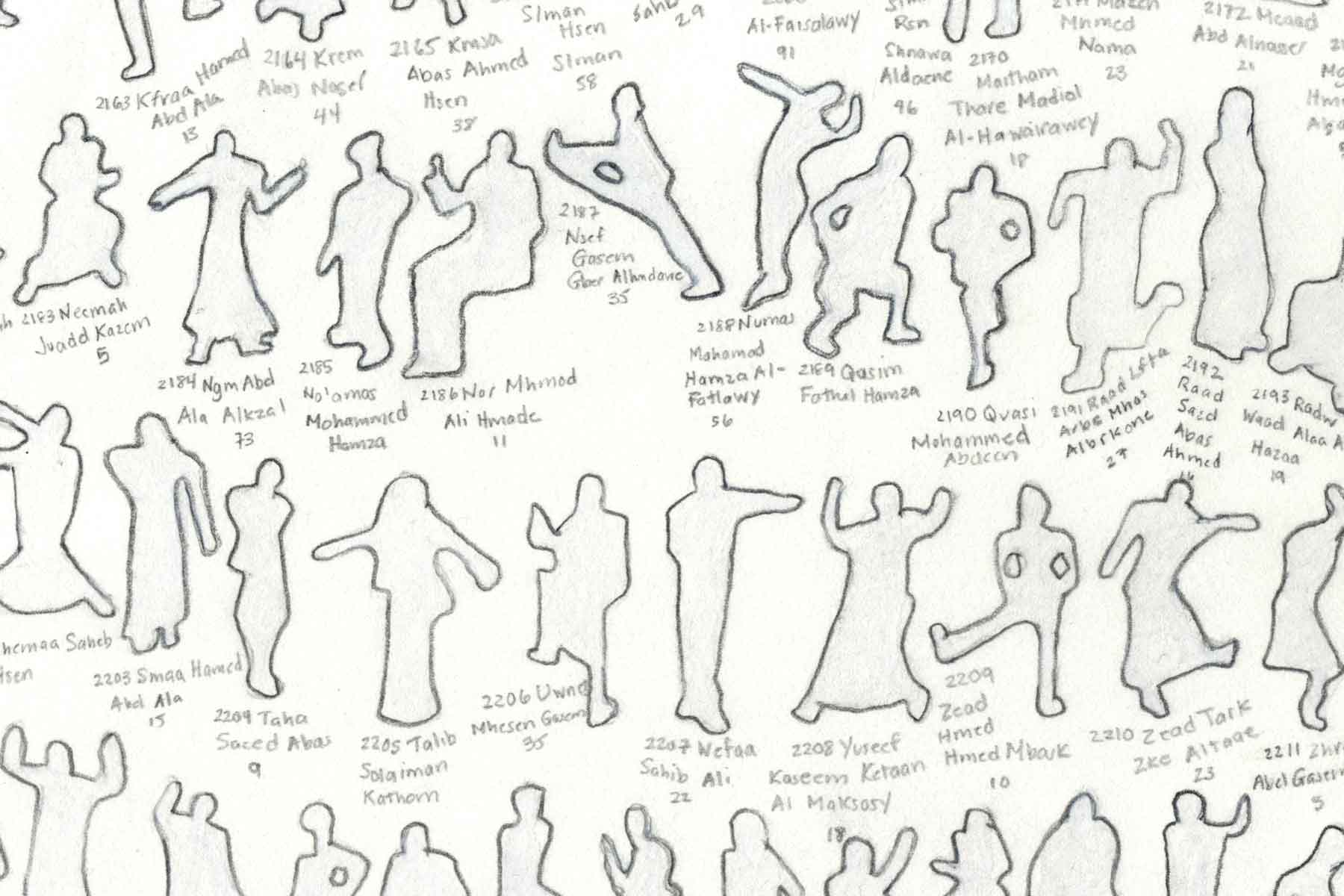

Elise Engler, Collateral Damage #3 (of 18), 2003-2008, color pencil on paper, 18 drawings, each 60” x 12". Courtesy of the artist.

Elise Engler merges archive as source, process and form, actually creating visual archives. She uses common, everyday objects or a proposition about people or available things to show how the material culture defines a place, the identities of the owners, or the priorities of a culture. Engler began this direction in her work when she was searching for a new iconography and archiving became her source.1 In the mid-1990s, she went to have dinner at the home of two friends who owned just two plates, two sets of utensils and two cups for the two of them, prompting them to buy additional implements for her to use. The couple later visited her apartment, and because of this encounter she decided to examine everything she owned in detailed drawings that would eventually become Everything I Own (1997-98), a series of 17 vertically oriented, large-format, color-pencil drawings on paper (each five foot by one foot) she made over the next 18 months of 13,127 objects in her home, in which each object is rendered just large enough to be identifiable to the viewer. Engler remarked on its origins: “Initially, I kept the project secret. I wanted to document my stuff. I had rules that I followed, such as I had to get rid of anything I didn’t draw. I wouldn’t have any secrets in the piece. I created order through the process. I’m a teaching artist and child of Depression-era parents who kept 50 rolls of toilet paper at once.”

Word of the project got out, and people started showing interest. The series became a catalyst for Engler to document and catalogue, she says. “Whenever I am settled down, I gather all the information possible, all of the physical or material manifestations of a situation.” She doesn’t regard herself as an archivist, but instead uses the moniker “Ms. Documentrix,” which is the address for her website.

Engler considers herself a visual journalist, creating a portrait of a subject, person, space or place. “I go in and draw everything,” she says. “I order it to create a narrative.” She transitioned from this initial project of creating a massive inventory of herself and her life through the contents of her apartment. She moved from personal consumption and environment into the public realm with the next work after exhibiting the first group. Aware of this first set, the non-profit Art in General invited her to draw all the art that came into the space as part of a group show about scale.

Soon after, Engler shifted this approach into a political direction when she began her Tax Dollars series of 2003-8, which began as examinations of all the chairs in a public-school classroom, the contents of a government-funded virology laboratory or all the objects used to maintain Riverside Park in New York City, showing the incredible ways tax dollars impact our lives. Moved by the beginnings of the war, she began thinking about the repercussions of the U.S. dropping the first bombs in Iraq in March of 2003. She looked at the human casualties of the war, as well as all the objects and weapons used, in Iraq. “I wanted to create an almost neutral inventory so that instead of an obvious polemical/political anti-war statement, I could say, ‘Here’s the information, seen through my eyes, you decide what this war means,” Engler says. Despite being adamantly anti-war, she decided to look at the soldiers, the casualties of war, to avoid being disrespectful of their contribution.

Engler wanted to show them all, including the coalition and the civilians (mostly Iraqi), which became the group of drawings known as Wrapped in the Flag (military casualties) and Collateral Damage (Iraqi civilians) of 2006-present. She depicts each of the figures as a silhouette. This series of 35 drawings of over 22,000 figures (as of 2008) are each five feet by one foot. She emphasizes that they were very respectfully drawn. But she always wanted her conclusion to be understood that the travesty of the war was clear in her work. And she wanted to draw the viewer into a large installation of the drawings with the splayed figures being read as active, as though they were dancing. Then, once close to the drawings, the viewer would change to a response deeper in nature. The soldiers are drawn on a grid pattern-linear and organized with numbered figures, 10 or 12 people per line-filled in with patterns of the flag from their country of origin (initially 19 different countries, then just American) and the names and ages under each. The civilian casualties were filled in with white pencil and had the names underneath, also numbered. However, they were not in an ordered, linear, gridded format. The difference in the organization signaled the distinction between military and civilian life. “The reaction to this series was powerful. Viewers think they are action figures, then they are shocked. The whole installation took up 40 feet of wall in the gallery,” Engler says. She continues to create these archives of places and people, which become portraits.

These archive-related or archive-generated projects all share a highly conceptual approach to art-making. Highly experimental, yet intensely rich and complex, they offer a range of images of women’s experiences through the eyes of these artists. All of these projects are open-ended so the viewer may decide how history and our notion of ourselves intersect. They tease out the disjunctions and inconsistencies in the narratives we use to organize our lives, highlighting new ways of reading and experiencing our familiar surroundings.

NOTES

1. All comments and quotations by Elise Engler from the author’s telephone interview with the artist, October 22, 2012.

Anne Swartz is a professor of art history at the Savannah College of Art and Design. She has focused her lectures, writings and curatorial projects on feminist artists, critical theory and new media/new genre. She’s currently co-editing The Question of the Girl with Jillian St. Jacques, as well as completing Female Sexualities in Contemporary Art, a compilation of her essays, and The History of New Media/New Genre: From John Cage to Now, a survey of developments in recent art.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.