« Reviews

Sharon Hayes: There’s So Much I Want to Say to You

Sharon Hayes An Ear to the Sounds of Our History (Longest Day), 2011, digital C-print. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

Whitney Museum of American Art - New York

“The Impossibility of Protest from Within the Institution”

By Stephen Truax

Artist and activist Sharon Hayes’ ongoing projects pairing political protest and personal desire exhibited together at the Whitney Museum of American Art illuminated how drastically the present political landscape differs from that of the 20th century. Hayes gathered source materials through extensive research on historical and current radical and subcultural political movements to create works that explore the aesthetics of protest. The show conflated various political initiatives (civil rights, gay rights, anti-war, anti-corporation, etc.) into an angry lump. Hayes exercised little restraint in voicing her own views.

Collaborating with artist Andrea Geyer, Hayes built an environment in raw plywood and platform seating in the language of art fairs and corporate conventions. Stretched canvas stapled directly into the plywood wall served as scrims for video projections. In their attempt to make the museum less “institutional,” they managed to make the Breuer building even more oppressive.

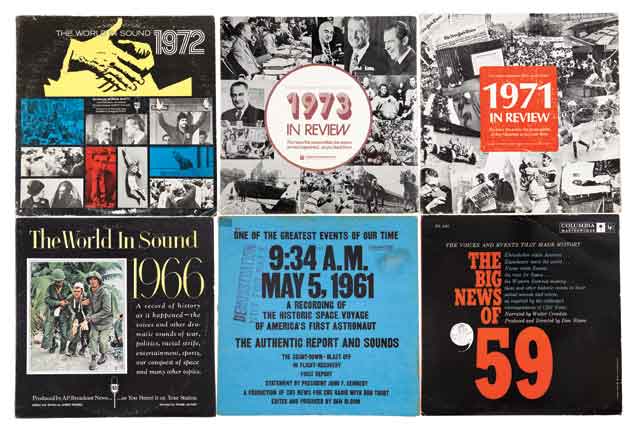

There’s So Much I Want to Say to You (2012) had a strong nostalgia for the radicalism 1960s and 1970s and the theoretical tactics of the 1990s. Her extensive collection of original vinyl records-their original method of distribution-of spoken-word statements from the 1960s and 1970s from underground political groups lined the walls of the third floor of the museum. Six hundred 8 1/2-by-11-inch printed/copied flyers from archives of political movements from the 1960s to the present are hung in a loose grid a least 12 feet by 30 feet long that “refuses hierarchy and chronology”1 (i.e., they’re not organized.) Antique technologies held a prominent position: a record player, a film projector showing a documentary about the first pride parade (1970), and an overhead projector. Institutional critique seems to have not advanced very far politically or aesthetically since the 1990s, when Hayes came to prominence.

In an interview with The Huffington Post, Hayes admitted her discomfort with the institutional context. “I think there’s something where a museum by its nature legitimizes a work, validates a work, but that very validation closes something else off-by that I mean it makes all work seem more resolved than it might be.”2 While every effort was made by the artist and museum to present protest against power (in all its forms), one of the most important paradoxes of conceptual art circumvented its effect. According to Benjamin Buchloh, “In the absence of any specifically visual qualities…as a criterion of distinction…the definition of the aesthetic becomes…the function of both a legal contract and an institutional discourse (a discourse of power rather than taste).”3 How can an effective protest against power be launched from within the walls of the institution-the quintessential image of power and exclusivity, the very thing that assigned her work legitimacy?

Intimate personal statements of longing from a-or her?-gay love life were interspersed amidst the political dialogue, as in Everything Else Has Failed! Don‘t You Think It‘s Time for Love? (2007). As it happens, many of these were appropriated from anonymous love letters. To do something so vulnerable as to use her own love letters would have allowed the viewer to have an actual emotional dialogue with the work or the artist; instead, we were left with a strictly theoretical one.

It is extremely difficult to review Hayes’ work. She positions herself as anti-war, anti-corporation, pro-equality, pro-gay and defender of the underdog. Naturally, these are all positions on which the vast majority of the global art community-but even more so in New York-agree. This argument against Hayes’ presentation is not one of political disagreement, but rather, searching for the refinement, subtlety and nuance of our political-artistic discourse. Such a task requires reimagining our aesthetics and tactics of speaking truth to power, to not merely mimic 20th-century activism, but to create something new.

(June 21 - September 9, 2012)

NOTES

1. Statement, Whitney Museum of American Art.

2. “Sharon Hayes Performance ‘There’s So Much I Want To Say To You’ at the Whitney Museum Of American Art.” The Huffington Post. June 23, 2012.

3. Buchloh, Benjamin H.D., “Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the aesthetic of administration to the critique of institutions,” Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (eds.), Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

Stephen Truax is an artist, writer and independent curator based in Brooklyn.

Filed Under: Reviews

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.