« Features

Calculating Uncertainty. A Conversation with Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer is a Mexican media artist based in Montreal, Québec, who has been developing interactive installations for over two decades. He was the first artist to represent Mexico in the Venice Biennale, in 2007, with a solo show that included his biometric installation Pulse Room: a room composed of hundreds of clear incandescent light bulbs, which glimmer to the recorded heart beats of participants who held a heart-rate sensor. Imagine witnessing a bulb above you flashing at the exact rhythm of your heart, then to advance down the line to the following bulb, joining the existing recordings of the previous visitors’ pulses and advancing the flashing sequence, to then give way to the heart rate of the next participant.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer is a Mexican media artist based in Montreal, Québec, who has been developing interactive installations for over two decades. He was the first artist to represent Mexico in the Venice Biennale, in 2007, with a solo show that included his biometric installation Pulse Room: a room composed of hundreds of clear incandescent light bulbs, which glimmer to the recorded heart beats of participants who held a heart-rate sensor. Imagine witnessing a bulb above you flashing at the exact rhythm of your heart, then to advance down the line to the following bulb, joining the existing recordings of the previous visitors’ pulses and advancing the flashing sequence, to then give way to the heart rate of the next participant.

Lozano-Hemmer’s work exists in an arena that not only bridges architecture and performance art, but also through his programming of control technologies he creates a platform for public participation. In the wake of his latest exhibition “Pseudomatisms,” curated by José Luis Barrios and Alejandra Labastida at Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City, Rafael and I conversed about the relationship between technology, the physical and political body, and how art creates a context through which we can investigate and illustrate these relationships.

BY OTHIANA ROFFIEL

Othiana Roffiel - Rafael, your background is in science. When did you take the leap into the art world and what made you take it?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer - My parents were nightclub owners, and I grew up surrounded by musicians, writers, dancers and visual artists. So right after I finished a degree in physical chemistry I quickly hooked up with friends in the arts and began doing performance art with them.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Pulse Room, 2006, incandescent light bulbs, voltage controllers, heart rate sensors, computer, stainless steel stand, variable dimensions. Photo: Oliver Santana.

O.R. - “Pseudomatisms,” your first comprehensive museum exhibition in your native country (10/28/2015 - 04/17/2016) features 42 pieces that span 23 years of production using interactive video, robotics, computerized surveillance, photography and sound sculpture. The title of the show clearly alludes to the surrealist automatisms yet transcends this notion posing the impossibility of true randomness. Is this due to the idea that a machine can never be truly autonomous because not only is it created by humans but acting in response to us?

R.LH - This is due to the mathematical impossibility of randomness. By definition, if a machine can output truly random numbers then they could not be produced by an equation, algorithm or method in the first place! Another way to say this: If you can generate a random number with a function then the number is not random, as the function can be used again to repeat it. So this conundrum has generated an entire branch of mathematics called ‘random number generation,’ which tries to approximate the uncertain. This lack of uncertainty is the key reason true automatism does not exist in the computer world and one reason poetry will always be important in our cybernetic future.

Rafael Lozano Hemmer next to Sphere Packing: Luigi Nono, 2014, ceramic 3D print, 70 audio channels, stainless steel, electronic cards, Arduino. 4 23/32” diameter. Photo: David González.

O.R. - “Poetry will always be important in our cybernetic future.” I definitely see this statement reflected in many places of your work (though I imagine some might think poetry and technology exist in different realms). The pieces in “Pseudomatisms” inevitably take me on a passage through poetry, music, science and literature, as you make references to key texts and works of the past. The title of the piece Nothing Is More Optimistic than Stjärnsund (2010) references Carolus Linnaeus, father of modern ecology; Bifurcation (2012) is inspired by the writing of Octavio Paz and Bioy Casares; Cardinal Directions (2010) geo-locates a fragment of a poem by Vicente Huidobro; and in Sphere Packing (2013-2015) you play the music of nearly a dozen legendary composers. Can you talk more in depth about the influence these figures (which often even go beyond the confines of the art world) have on your creative process?

R.LH - The beauty of poetry is often precisely its ambiguity, its capability to mean different things to different readers. I love works of art that have loose ends that you may follow to an unpredictable end. ‘Getting lost’ in a piece has always been the best compliment. And I know that my pieces are likewise out of my control. Being inspired by, and citing, precedents is important because I reject the term ‘new’ media, I do not believe what I am doing is original or futuristic and want my pieces instead to be in relation to other existing content or experiments.

O.R. - Exactly, besides the inspiration you receive from the key historical figures mentioned above, you are also working upon a strong legacy of artists both conceptually and technologically. You break the idea that what you are doing is ‘new’ media by explaining that, for example, Wodiczko was doing projection mapping 30 years back. Simultaneously you recognize that lineage of Latin American artists who have built strong foundations but have not been recognized, perhaps relegated to the shadows. Can you tell us more about the legacy you are working upon? About how your work relates to this existing content you mention?

R.LH - My show at MUAC features almost 30 cameras trained on the public. When someone asks me if the show uses new media I like to mention that Argentinian artist Marta Minujín first used video cameras to mix the live images of the public with TV in 1965. I love to mention that precedent because she was the real pioneer of live video in art installations, using the cameras before Nam June Paik for example, and as a Latin-American woman she breaks many stereotypes. But also, this was over 50 years ago! How can we call ‘new’ something that has been done for five decades? To me, it is more like a tradition of experimentation. In Mexico we have the Estridentista poets like Maples Arce, who were the pioneers of radio broadcast in the 1920s, the postulation of the theory of Cybernetics by Norbert Weiner when he was working with Arturo Rosenblueth in the 1930s at the National Institute of Cardiology, the patent of color TV by González Camarena in the 1940s, the early computer drawings by Manuel Felguérez in the 1960s, and many other nerdy precedents that should be better known.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Krzysztof Wodiczko, Zoom Pavilion, 2015, projectors, infrared cameras, robotic zoom cameras, computers, IR illuminators, ethernet switch, HDMI and USB extenders and cables, variable dimensions. Photo: Antimodular Research.

O.R. - I find the layout of ”Pseudomatisms” very significant. You are taken from one room to another in an aesthetic voyage, and even though there is a strong discourse that guides us across the whole exhibition, each area possesses its own conceptual subplots. Could you tell us more about this curatorial aspect of “Pseudomatisms?”

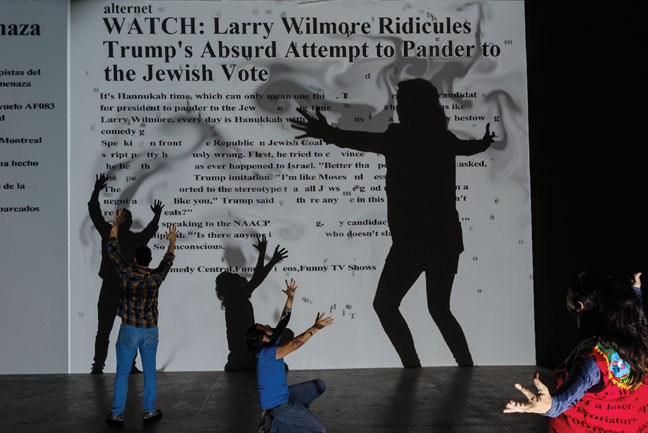

R.LH - I can, although my notes are not prescriptive, they are just informal lines of discussion I had with the curators. Hopefully the visitor can make up his or her own narratives. The first room has two pieces that address the concept of atmospheric memory, the idea that our atmosphere is not a neutral space. The next room has pieces that somehow materialize metrics and control. Next is a kind of ‘hall of shadows,’ with pieces that function with embodied interaction. Then there is a room with four Pseudomatisms and, finally, three big installations about biometry and phantasmagoria. Throughout the show there are other conceptual lines and certainly a play of scales, materials and approaches.

O.R. - Rafael, you mentioned ‘atmospheric memory’ in this first room, is this because we are all inhaling the same tiny gold particles coming from the piece Babbage Nanopamphlets (2014)? Or breathing the same air in the sealed glass room of Vicious Circular Breathing (2013)? Even though we read the warnings of coming in contact with that compromised air we still decide to go into this stuffy, closed space. Why? In my eyes, we want to belong. The most intimate and individual components of our being, such as our breath, become one with the piece and with the breath of other visitors, thus proving perhaps that not even our breath can truly be intimate or individual; like you said, that ‘our atmosphere is not a neutral space.’ With this in mind, what weight does the collective experience carry in your work?

R.LH - The text engraved onto the tiny gold nanopamphlets that people inhale upon entering the exhibition is an excerpt from the Ninth Bridgewater Treatise (1837) by English polymath and “father of the computer” Charles Babbage. The quote posits that the atmosphere is a vast repository of everything that has ever been said and that we could potentially “rewind” the movement of air molecules to re-create the voices of everyone who has spoken in the past. I love that in Babbage’s vision we coexist with the voices from the past. In Vicious Circular Breathing, the other installation in the room, you are invited to enter a hermetically sealed chamber to breathe the stale air that has already been breathed by everyone before you. I don’t want so much to produce a collective experience as I want people to think about limits to the commons, the resources we share like water, air, solar energy and so on. Also, in this piece I like that the air that is in your body, in your lungs, becomes the public air after exhalation and vice versa. There is a constant transformation of the private into the public that makes evident the continuity between them.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Airborne Projection, 2015, projectors, computers, surveillance cameras, newsfeeds, variable dimensions. Photo: Oliver Santana.

O.R. - This diversity of scale present in “Pseudomatisms” greatly intrigues me. I know you usually like to go ‘big,’ yet for this show you are playing with a wide range of sizes. From engraving a text so small that it can fit on the surface of a gold leaflet and float unseen in the air, to colossal pieces that take over a huge room such as Zoom Pavilion (2015). For me, this diversity of scale in “Pseudomatisms” enhances the aesthetic and conceptual journey of the visitor. Yet I wonder about two projects that are similar in content but have radically different scales: In Eye Contact (2006) exhibited in “Pseudomatisms,” we see a single interactive screen depicting 800 simultaneous miniature videos of people lying down. Once the spectator is detected through a built-in computerized tracking system, the people in the videos wake up and directly observe the visitor, prompting the question who is the observer and who is the observed. In a previous work in public space, Under Scan (2005), the same images were projected, but rather on a human scale, scattered across the floor of a plaza, occupying the shadows of passers-by. How do you feel this change in scale affects how the spectator interacts with the piece? And also, how different is the experience of working in a museum setting than in the public arena?

R.LH - I often joke that my work is as big as my insecurities. For example, using the brightest projectors or the largest aerostats, but now that I go to psychotherapy I am okay with making little pieces. Certainly scale matters, often large scale is important to create immersive experiences or to amplify participation to an urban scale, for example. But with large projects it is important to turn intimidation into intimacy-in other words, instead of having colossal displays that are monologues of power (think Albert Speer, a corporate presentation or a Son et lumière show on a heritage building) we seek to create platforms for people to self-represent and personalize public space. With exhibitions in a museum the scale provides an easier path for intimacy but you lose a lot of the spontaneity you may find in public space. In general, the production at my studio is split equally between large commissions for public space and smaller pieces meant for collection; the themes and approaches are often similar but with different results.

O.R. - Speaking of museums, “Pseudomatisms” is not only taking place under the complex sociopolitical climate of Mexico, but it is also being shown in the grounds of UNAM, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, an educational institution carrying an enormous historical weight. You decided to include Level of Confidence (2015) in the entrance of the museum, even though this piece is technically not part of the show, which searches for the 43 disappeared students from the Ayotzinapa normalista school in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico back in September of 2014, a piece about kidnapped students being shown in one of the most important educational institutions of Latin America. Can you tell us more about the context in which “Pseudomatisms” is being exhibited?

R.LH - The piece Level of Confidence is a computerized surveillance system that has been programmed to look for the disappeared students incessantly. It analyzes the facial features of anyone passing by and compares these to the features of the 43 students, creating a match and offering a level of confidence specifying how close the match is, in percent. The piece subverts the way these police technologies are used; instead of looking for suspicious culprits we search for the victims. The piece is not really an artwork but rather a device to maintain visibility on the tragedy, a tool to create empathy and a way to generate funds for the community, as all proceeds from the piece go to the families of the students. I developed the project as a citizen to react to the appalling reality that the students have not been found. The project is viral in that anyone can download the software and source code of the piece for free from my website, optionally transferring some money to the shared bank account of the parents; so far we have shown the piece in universities, museums, galleries and foundations all over Mexico and in over 10 countries. A final aspect of this piece is that it is open source. Any programmer can reuse our code to create their own version, so for example in Argentina it is being reprogrammed to look for the tens of thousands of disappeared during the dictatorship and in Canada to look for the over 1,000 aboriginal women that have gone missing in the past few years.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Vicious Circular Breathing, 2013 sealed glass prism with automated sliding door system, motorized bellows, electromagnetic valve manifold, 61 brown paper bags, custom circuitry, respiration tubing, sensors, computer. Variable dimensions, the glass prism measures 243 x 243 x 243 cm. Borusan Contemporary Collection, Istanbul. Photo: Oliver Santana.

O.R. - You use similar technological tools for certain pieces, yet many critics have classified them into two different conceptual arenas. The first perhaps of a more playful air, like Sandbox (2010), in which people on the beach play with the colossal images being projected on the sand that are created by a group of passersby having equally as much fun. You might as well be in a carnival. The second, with a more Orwellian tone to it, portrays the implications of surveillance technologies or even makes direct reference to extremely delicate social circumstances such as Voz Alta (Loud Voice) (2008) in which you honor the students massacred in Tlatelolco Plaza in Mexico City in 1968. What are your thoughts on these two readings of your work?

R.LH - Indeed my work is often interpreted as either being playful (a videogame, a special effect) or as a moralist depiction or cautionary tale of a technological dystopia (predatory vision, Orwellian tracking). However, in my opinion, these things exist in a continuum. For me, a playful piece can also be very political, critical and dark. It completely depends on the public’s participation and the context. Likewise, a piece that is intended as a stark representation of computerized control can be extremely connective and fun. In the MUAC exhibition the piece Airborne represents this continuum nicely: As people pass by, their tracked shadows disturb projected news cables coming live from Reuters, AP, Notimex, EFE, Alternet and other sources. People’s experience of the work will very much depend on what piece of real-time news they happen to interact with.

O.R. - In the interactive installation, Zoom Pavilion (2015), as the viewer walks in the gallery space their face is projected and magnified onto the walls as it is being detected and recorded by face recognition algorithms. A situation is created in which you inevitably become aware not only of your corporality and presence but are connected with other spectators and to the exhibition space in itself. You are simultaneously disoriented by the constant movement of the zooming sequences, enthralled by your own images on the museum’s walls, but also weary as you become aware of the predatory nature of these technologies. For this piece, you collaborated for the first time with artist Krzysztof Wodiczko. Both of your practices involve the transformation of public spaces, often through the use of similar technologies such as projectors, yet at the same time your work tends to be more ‘relationship specific’ and Wodiczko’s leans more towards ‘site specific.’ Could you go more in depth into Zoom Pavilion and how both of your practices complement each other for the piece?

R.LH - I met Krzysztof a few years ago and we quickly became friends. I have admired his work for a long time, and he is one of the most elegant, thoughtful and critical artists I have ever met. The piece Zoom Pavilion was originally designed for the Beijing Architecture Biennial and was meant to be staged in a public space just outside the bird’s nest Olympic Stadium. In the end, we did not get permission to show the work, perhaps because it entails a surveillance system that tracks people with 12 cameras and records their spatial relationships. For the piece we worked in my studio in Montreal and then also in Mexico once the gear was installed at the museum. The collaboration was fluid because we are both interested in making tangible the way surveillance is, not just about individuals but about tracking assemblies of people.

O.R. - You are constantly trying to break certain stereotypes of the art world and expand paradigms. You go beyond the ideal of the artist as this solitary figure, the sole creator of a piece, and rather refer to yourself as the manager of a team. In my eyes, you are the director of a play, your team are the set, sound, lighting and dress designers, and your machines become the actors. Yet the curtain cannot be opened without an audience. The performance needs to be activated by the spectator. Can you tell us more about this collaborative nature of your practice?

R.LH - Indeed, I have always thought of my work being closer to the performing arts than to the visual arts. I am lucky to work with a team of excellent programmers, artists and architects in my studio in Montreal, and in addition, we often collaborate with others. If you look at my website for each piece, there are credits for all developers. In the art world, many times collaborators are not acknowledged perhaps because of the old stereotype of the solitary artist working in front of his or her canvas. And yes, once a piece leaves my studio it is unfinished, incomplete: Many of my works depend on participation to exist, and the content is derived from interaction, so the public has an integral role in the way the piece emerges.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Level of Confidence, 2015, face-recognition algorithms, computer, screen, Webcams, variable dimensions. Photo: Antimodular Research.

O.R. - And even going beyond that, you break this idea of the ‘secrecy’ behind the creative process. Instead, you do the opposite and openly share many aspects of your methodology. For “Pseudomatisms,” you not only uploaded the complete PDF file of the catalogue online but decided to publish a USB drive in which you share all the code and schematics used to create the pieces with the public. You thus create an important precedent, as “Pseudomatisms” becomes the first comprehensive art show that shares data of the development process that other programmers can use to build their own pieces. It is obvious that this is something very important for you. Can you go a little more in depth into the why?

R.LH - At my studio, we often start our projects using open source software and hardware, and we firmly believe in that philosophy of sharing the fundamental instructions, methods, schematics and code used to develop. We love the non-corporate, non-proprietary aspects of that approach and the idea that other programmers could benefit from our research. In addition, it helps for preservation because in the future if a piece malfunctions any programmer can look at those fundamental instructions and re-create the work in a future platform. In this sense our computer code is not unlike the instructions used by Sol LeWitt, Félix González-Torres or Tino Sehgal to create their work, and this helps conservation departments at museums understand the sustainability of media art.

O.R. - Rafael, where is “Pseudomatisms” going after MUAC?

R.LH - We are currently negotiating taking it to SESC in Sao Paulo and to the Musée d’art contemporain in Montréal. I am eager to see how the pieces change as the show travels and different publics interact with it.

Othiana Roffiel is an artist and writer based in Mexico City. She is a fine arts graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design. Aside from the development of her body of work, she has been instrumental in fostering the international conversation about the state of contemporary art through her publications in diverse international forums such as ARTPULSE and Artishock.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.