« Features

DIALOGUES FOR A NEW MILLENNIUM. Interview with Pablo Helguera

Pablo Helguera (1971, Mexico City) is an interdisciplinary artist and Director of Adult and Academic Programs in the Department of Education at the MoMA, New York. Our conversation evolves around concepts like inclusion-exclusion, active and passive participation, performance and its reproduction, and the validity of art activism today.

By Paco Barragán

Paco Barragán -As Georgia Kotretsos said in her foreword of your most recent Artoon: you’re a contortionist. I think that is an intriguing starting point for this conversation.

Pablo Helguera -There is a scene from the movie Big Night where a character says: “I am a businessman. I am whatever I need to be at anytime.” Now, I am not a businessman, nor am I capable of transforming into anything that can be financially productive. But I am trained as a performer. As such, one is trained to perform a variety of social roles. You can, if you need to, be different people. We all kind of have to, in order to survive in a hostile creative environment. And in our strange postmodern times, it so happens that all have to perform a variety of roles from a repertoire of multiple traditions, ideas, etc. So it is not so much of a choice. But I am happy with that necessity because I don’t want to be just one person anyway-I can’t help but to want to explore what it is like to be many people at the same time. For my first solo exhibition in Mexico City, I created fourteen different artists with different styles, histories, nationalities, and so forth, and advertised the show as a group show. No one knew that I had made all the works (I was officially only one of the artists in the show). It was liberating.

P.B.-You’re very interdisciplinary within your artistic practice, be it performance, conceptual art, or drawing, and you’re known not only for being an artist, but also a writer, occasionally a curator, and Director of Adult and Academic Programs in the Department of Education at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. How do all these facets coexist?

P.H.- The one thing I will never be is an exhibition curator. But I do, I suppose, curate voices-a description that a friend, Valerie Cassel, once used when referring to the very strange species of profession that some of us work in, which is the one of the public programmer. Over the course of twenty years, I have organized nearly one thousand lectures, panel discussions, symposia, and similar events. Beyond that, it is not a stretch to be an artist and an educator. For many, art making and learning are one and the same. Writing is where it all comes together for me. To me, the world is nothing but a potential to create scripts-visual, verbal, theatrical, social, and theoretical. Art to me is the manifestation of a script, and life is a script in the making.

P.B.-Could we say then there is a ‘performative’ element to it that acts as common thread?

P.H.-I think the reason I see everything as a potential script is because I see performativity everywhere. It permeates social fabric, social interactions, anything that we do or say or make. Scripting it is just the process of delineating it, like making a drawing of a performance but using words instead. Artoons is nothing but the representation of what I see as the social script of the art world, as well as the theater works or other pieces that refer to it.

PERFORMANCE, THEATRICALITY, AND REPRODUCTION

P.B.-Performance, or as I rather like to say “the performative” is an important part of your artistic practice, from projects like Theatrum Anatomicum, What in the World: A Museums Subjective Biography to The School of Panamerican Unrest. Michael Fried wrote in his seminal essay “Art and Objecthood” (Artforum 5, 10 [Summer issue 1967], p. 21) referring to Minimalism that art degenerates the more it overlaps with theater, since the theatrical is what lies ‘between’ the arts (between painting and sculpture). Theatricality also implies a concern with time, or rather with the duration of experience. And performance is the genre that experiments more with interdisciplinarity and the time factor, key elements in your practice.

P.H.- Fried’s critique, as I understand it, was that Minimalist sculpture is a degraded form of art when it engages in theatricality (which, in retrospect, may sound to us a bit ironic, since he was referring to static art as some kind of theatrical event). He was correct, though, because the same critical spirit of that position can be seen in the generational answer to Minimalism, what would eventually become performance art (which tried to break the boundaries between the art object and the viewer) and institutional critique, which is an attempt to display the, say, theatrical devices that reinforce the hierarchies of the spectator, the institution, and the art object. I obviously come from both of those traditions, but precisely because of that my embracing of theatrical devices already comes with a certain filter. For one thing, I am also not interested in theatricality per se, but I am interested in the traditional mechanisms of theater as they are inserted into reality (which is why I started scripting panel discussions and symposia and presenting them to audiences as if they were real life things). Theater provides you with an incredible structure to enhance reality, but you have to use it in a way in which it does not create a psychological distance with the spectator or emphasize the so-called fourth wall. Museums like Dia: Beacon, Fried would argue, are the stage onto which the drama of Minimalist sculpture unfolds. But the way many of us who work in between performance and theater-I think of colleagues like Tim Etchells, David Levine, Emily Mast, etc.-use theater today is really beyond that, as we now feel the freedom to ironize and play with the conventions of theater.

P.B.-The institutional critique that you just mentioned reminds us once again that many artistic practices that were anti-institutional end(ed) up being swallowed by the system, just as has happened with performance art and the many unstoppable retrospectives in museums around the world, like the famous Marina Abramovic retrospective at MoMA. In one of your cartoons you deal with it. I’m referring to the scene in which one fakir says to another: “I’ve told you already: the fact I believe in reincarnation doesn’t mean I believe in re-performance. When I saw the iconic naked performance by Abramovic and Ulay performed by students I had this same feeling of awkward déjà vu…”

P.H. -Sometimes I feel a day doesn’t pass that I don’t have a conversation about Marina’s show. Whatever one thinks about that exhibition, the fact is that it reframed the debate around, what I would call “performance and its mechanical reproduction.” The Artoon you mention ironizes on this implicit idea that performance art can be reincarnated as some sort of spiritual soul-transfer of the artist onto whomever. I don’t have any problems with works that have been made to be performed, interpreted, etc., like most of the entire theatrical, musical, and dance tradition. I am less sure about the retroactive reperformance of the works that were originally intended to be ephemeral-to me that is suspect as it works alongside the market benefits of the idea, and we all know that performance art in the 60s and 70s was everything but an attempt to be part of the market: it was about emphasizing the living moment. What I am completely sure about is the value of the unrepeatable performance, which has recently led me to make a number of performances that can never be performed again. Sometimes it is better to disperse performance into the ether.

EDUCATION, AUDIENCE DESIGN, AND THE EMANCIPATED SPECTATOR

P.B.-Performance offers a direct, vivid product that does not (on many occasions) need mediation. It takes place before a public and it needs a public. So basically we could say it’s about ‘making art public.’ You are connected to the public and to audiences both as an artist and as an educator. How has your experience as an artist informed your work as an educator, and vice versa?

P.H. - They have always been together, so I don’t know how it could be different. I came to the field of museum education by accident; like many, I was trying to find a way to make a living, and because I am Mexican and bilingual, I was a good fit in a museum education department. Only later I realized the extent to which what I was learning about interaction with audiences and collaborative dialogues was connected to the interest in the viewer by artists involved in institutional critique and process-based, collaborative practices. It also allowed me to obtain a certain critical perspective on public art. To this day, one constantly informs the other. The main difference is that when I operate as an artist, I am free to direct the kind of research or project, and when I operate as an educator, I am part of a larger process, and I have to learn to be collaborator, to support, and if necessary, to recede into the background.

P.B.-You have expressed on several occasions the idea that contemporary art practices are about exclusion, not inclusion, based on certain social codes. How does this affect the idea of audience education? Can we deduce that certain institutions like MoMA, for example, target concrete audiences that qualify as such according to their parameters?

P.H. -When I usually refer to the system of exclusion in the art world, I am referring to how those of us in the inner circles of its social system (that is, those who are by profession connected to art) create a number of boundaries and codes so that the system remains exclusive and, by it being so, positions us in a higher role as protagonists while the public remains a passive observer or consumer of what we do. Art education is about showing that the process of making art, and creativity in general, is not something exclusive nor unattainable, and while not everyone can or wants to become a professional artist, everyone is and should be able to use art as a way to express themselves, often in original ways. In that sense, good museum education is not about exclusion but about inclusion and agency. Do you think that large museums pick and choose who visits them? They can barely keep up with the thousands upon thousands of visitors, requests, school visits, and solicitations from all kinds of groups! On the contrary, they have to create ways through which these demands can be met. And it is in the interest of every museum director to get as large a visitation as possible-it’s all about attendance because attendance translates into revenue, membership, funding, and all the basics that allow an institution to thrive and grow. Education is a way in which artists become engaged in a meaningful way at every level of the social spectrum, and that is how I see my role as a museum educator. The problem rather lies with those places-be it museums, kunsthalles, etc.-that do not have a serious commitment to education. You may see programs that are supposedly intended to be educational but in actuality are extensions of the system of exclusivity that plagues the art world as you actually need to speak the academic/theoretical/cultural language of a group of people in order to fit in. It functions closer to a club, one which one slowly enters as one learns the basic social codes, the right phrases, the right books, and the right things to like and dislike. It is, if you may, a social education, but one ultimately of admission through submission.

P.B.-The linguistic element in your work is very important, and also in your educational practice. This reminds me of the innovative sociolinguistic model outlined by Allan Bell in 1984 which proposed that linguistic ‘style-shifting’ occurs primarily in response to a speaker’s audience. How does this affect your decisions regarding hypothetical audiences?

P.H. - I have done quite a variety of performances in the past using style-shifting-particularly a piece entitled Variations on an Audience (http://pablohelguera.net/2009/10/variations-on-an-audience-2009/)-where I literally adopt four different simultaneous voices to deliver the same speech. Less literally, however, ever since that early fake group show I was referring to, I’ve been using style-shifting without actually knowing it, appropriating the voice of the critic, the curator, the famous artist, the unknown one, the educator, and so forth. It really is a skill that one has to develop in standup comedy but also in museum education, when one is giving a gallery talk and has to adjust his or her language depending on who the visitor is.

I do think a lot about the audience I am going to encounter at a particular instance. It definitely determines a lot of what I am going to do, whether I am to speak or perform for a group of academics, of art students, of random people on the street, to non-art professionals, to visitors in a gallery in Germany or in a remote town in Honduras. It is not a scientific thing, but you still have to familiarize yourself with the situation and do what you think may be most appropriate. Going back to the exclusivist question, one of the things that I often encounter is that in most contemporary art places, no one cares about modifying their language; they are not even aware that they speak in a coded, incestuous vocabulary that has little meaning to anyone slightly outside of the “trade.”

P.B. - This could lead us to the spectator as such. Since conceptual art practices and especially New Institutionalism, there is this big issue about a more intelligent and active spectator, and many contemporary exhibits tackle this issue. As happens with the art world which is always looking for new Gods, everybody references Ranciere’s essay Le spectateur émancipé (The Emancipated Spectator). It’s a great title, but nothing more, and a great disappointment because it doesn’t offer one single idea about how we can emancipate the spectator, just the idea that the spectator is an active actor that makes the store intellectually his own, and it would be in this so-called act of association and dissociation where the emancipation of the spectator would lie. I rather find this cheap, old-fashioned rhetoric. In the end, and as for now, the spectator has to subject him/herself to the dictatorship of the curator and his script. Are there ways of emancipating the spectator or are we just beating around the bush once again?

P.H.- It is interesting that the two books by Rancière that became fashionable in the art world (The Ignorant Schoolmaster and The Emancipated Spectator) were quickly embraced by the art world as some kind of evangelical texts about pedagogy and performance, respectively. It is interesting first because they are not exactly representative of the breadth or the complexity of the work or the ideas that he has inserted in the public discourse, and also because, as you point out, they are not significant departures from the ideas of the 1960s that, for example, Guy Debord, Augusto Boal, or Paulo Freire had about emancipation.

Still, I don’t think it’s Rancière’s fault that the art world has elevated these books as some kind of breakthrough about issues of politics and social engagement in art. I am, however, grateful that these books have become points of discussion because in an indirect way they have helped to point to what really underlies these ideas-namely critical pedagogy, Adorno’s ideas on negative dialectics, etc.-and have opened a discussion about what the true legacy of the 60s is that we still need to update but haven’t quite managed to figure out how. And yes, I do believe that over the last few years we have seen interesting artworks that have attempted to seriously re-articulate what it means to be an active participant in an artwork-namely those works that now are generally described under the tag of social practice. Of equal importance, however, and this is something that Rancière doesn’t seem to recognize, audiences also want to exert their right to be passive, to willingly and happily submit to the actions of art by others. In other words, emancipation today doesn’t mean turning everyone into authors, but willingly giving away your authorship and becoming an old-fashioned audience member.

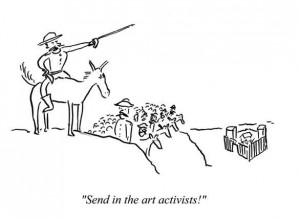

ART AND ACTIVISM

P.B. - Education can change attitudes on the long run, but I doubt if art can do so in a hyper-mediated society in which television, cinema, and advertising are competing with visual arts and have a strong capability of reaching and influencing audiences. In this sense, I was rather surprised by an article by Kate Taylor in the New York Times titled “US to Send Visual Artists as Cultural Ambassadors.” It basically said that this new program, smART POWER, will be administered by Holly Block and the Bronx Museum of the Arts, and it implied that visual artists will be sent to places that include Pakistan, Egypt, Venezuela, China, Nigeria, and a Somali refugee camp in Kenya. Isn’t it too pretentious to think artists can change people’s perceptions of the United States in those countries?

P.H. - Obviously, artists are not missionaries or superheroes that can transform the perception of an entire country, but I support a national program of arts exchange rather than making that exchange about sports or pop culture, which is often the case.

One of the reasons that art has lost its field of influence is because there has been a divorce between the contemporary art world and the world at large, which has included the almost complete lack of support from the U.S. government to its artists. You have seen a good reminder of this in the censorship case of the David Wojnarovicz piece at the Museum of American Art of the Smithsonian. So if the U.S. government is giving artists a chance to become cultural diplomats, you can’t throw your hands in the air and say that it is a hopeless cause for art to go out in the world and try to make a difference. On the contrary, we have to give it a try. I recognize that it is a romantic thing, and in fact I am guilty of it: the School of Panamerican Unrest was basically a project of international activism, although I recognized its own romanticism and perhaps naiveté. But the point of these projects, I think, is not to create a revolution but to offer models of thought or perception that may have a certain level of impact. Architects are perfect examples of this. Teddy Cruz in East L.A., Diébédo Francis Kéré in Burkina Faso, and Urban Think Tank in Caracas all have made self-sustainable projects that have had a real impact. We also have to remember that art historically has been ambassador of culture, and even if it is a marriage of convenience between artists and politicians, it is one that has produced important works. At the very least I would give the benefit of the doubt to the initiative.

P.B.- Lets give smART POWER the benefit of the doubt, then. Thank you for your time.