« Features

Push to Flush: Art Between Fame and Celebrity

Pablo Helguera, “Oh, those footnotes? She’s an academic”. 2010 (Artoon), drawing on paper. Courtesy of Pablo Helguera/Jorge Pinto Books Inc, New York.

By Paco Barragán

So you should always have a product that‘s not just “you.” An actress should count up her plays and movies and a model should count up her photographs and a writer should count up his words and an artist should count up his pictures so you always know exactly what you‘re worth, and you don‘t get stuck thinking your product is you and your fame, and your aura.

Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, 1975

Imagine two men wearing black suits, white shirts and black ties. One of them is drinking a Budweiser Light. They’re either in Qatar or Dubai. One looks like a rebel artist anguished about death, the other like a Chevrolet convertible salesman. That’s the beginning of Michel Houellebecq’s latest novel The Map and the Territory. It’s a novel about money, love, death, work and art. Photographer and main character Jed Martin is about to make portraits of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons.

It’s very rare for contemporary artists to be part of a novel’s plot. That is a privilege usually reserved for Old Masters such as Vermeer and Rembrandt, or, more recently, Picasso. But this unexpected detail is very revealing, as it signals the shift from fame to celebrity: not only famous but also celebrated people appear more and more in the spotlight in 21st-century capitalism.

The mix of consumerism, media society, popular culture, entertainment, glamour, the star system and Pop Art has transformed personhood into objecthood. Within a consumer society based on the inflation of the image, this “reification”-which, according to Marx, is inherent to capitalism-contributed to alienation, commodity fetishism and the superficiality of the subject. These traits characterize pretty well contemporary art’s esprit d‘époque, with its skyrocketing prices, parties and media celebrities. On top of that, the recent immediacy and mediation that social media has brought about has put even more pressure on our abilities to sustain a coherent image of ourselves and others.

My diagnosis formulated here should be of no surprise. As a result, we find ourselves in a situation in which “known for his well-knownness”-as Daniel Boorstin put it in the 1960s-has undeservedly devalued the merits of “fame.” Closer consideration reveals that too many intellectuals and art critics’ “fame” and “celebrity” refer essentialy to the same media phenomenon. But I would argue not at all, so I need to clear this terrible misconception first.1

FROM FAME TO CELEBRITY

Fame and celebrity are not interchangeable: fame is a process, celebrity is a state of being. Fame is already found in Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey around 500 to 400 B.C.; his term kleos afthiton translates as “imperishable fame,” and as David Giles keenly points out, “Throughout history it has been identified with “immortality, spiritual fame (in the eyes of God) and worldly fame (in the eyes of the public).”2 The defining characteristic of celebrity is that it is “essentially a media production,” and its usage is largely confined to the 20th century (Giles). This means that all of us can be treated as celebrities, whether we’re an anonymous clerk, a night porter or a gardener. Celebrity is basically the story of the mass media, starting with the Hollywood film industry (together with radio), which very soon created “personalities out of the stars;” later, the popularity of the television in the 1950s took over by bringing the stars into our homes; and at the wake of the new century, social media not only completed this transformation but also is competing with traditional mass media in its outrageous capacity to turn ordinary people into (temporary) stars. More so, as Leo Braudy said in the 1990s, the rise of visual culture of the 20th century has directed the media spotlight on to the body as never before.3 And I would add: on to anybody who is willing to sell his body for 15 seconds of celebrity.

Let’s manage without a table then. A quick comparison would be as follows: 1) fame equals reputation/skills and ability/product/object, and 2) celebrity stands for notoriety and recognition/well-knownness/person/subject. In recognizing the differences, we can also define the gray areas. The point is that mass media, especially television, started to treat individuals who had acquired well-deserved fame, like artists, architects, scientists, politicians, philosophers, writers, lawyers, and so on, as celebrities. And in some cases, like movie stars, pop stars, athletes, top models, fashion designers, writers, chefs, architects, etc., both fame and celebrity are reconciled in the same person as fans demand to know more and more about the intimacy of their personal lives, an intimacy that was, as we all know, part of the strategy and machinations of the early Hollywood star system.

Today, the art system, as well as politics and the everyday, function more and more with the codes, rules and dynamics of celebrity. Historically, artists such as Titian, Rembrandt, Rubens, Velázquez, Goya, Turner and Gauguin, and writers such as Dante, Chaucer and Erasmus, as well as monarchs and political leaders such as Philip II, Henry VIII, Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin, acquired fame through the invention of the printing press, engraving and portraiture. In the 20th century, artists such as Duchamp, Dali, Picasso, Pollock, Warhol, Schnabel, Koons and Hirst became celebrities with whom we as audience have built a strange relationship of intimacy: They’re strangers to us but through the media machine we seem to know everything about them.

The art world has become a business, a cultural industry, that functions almost like the fashion and film industry with its stars and top models, its photocalls, interviews, gossips, catwalks and premieres ruled by the celebrity principle.

Every social strata of the art industry has his/her shining star(s) who function de facto as tastemakers: Hirst, Koons and Marina Abramović; Saatchi and the Rubells; Hans Ulrich Obrist and Okwui Enwezor; Gagosian and Jay Joplin; Jeffrey Deitch and Thomas Krens; Jerry Saltz and Barry Schwabsky; Saskia Bos and Ute Meta Bauer; Hal Foster, Boris Groys and Jacques Rancière; the “name recognition” and the increasing promotion and publicity of these personae are clear symptoms of the ongoing integration of art into the entertainment industry. In this sense, we could paraphrase Joe Moran, who, referring to mediagenic best-selling writers, affirms that stardom becomes wholly self-fulfilling: The visibility of the arts celebrity name is used to bankroll products.(Moran, 329) Think of books, conferences, exhibitions, original art works and multiple editions, merchandising products, or his/her persona presence at a fundraising gala or other art events. And think now of Documenta. The most important exhibition has become a celebrity event that only confirms this unstoppable trend in the art world. The Logbook is a poignant and perfect example of superficiality: images of Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev (CCB) in Kabul, CCB in London, CCB in New York, CCB in Turin, CCB in Los Angeles, CCB with her dog, CCB with her husband…

The ongoing visibility of a kind of “major league” of events, which are covered by television, art and fashion magazines, and social media enhances the concept of contemporary artistic celebrity. Artistic “experiences” like biennials Venice and Documenta; art fairs such as Art Basel, Frieze and Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB); speculative auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s; the construction of spectacular museums like Guggenheim Bilbao, Tate Modern and Guggenheim Abu Dhabi; blockbusters like Sensation, and one busters like Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present at MoMA, Damien Hirst at Tate or Takashi Murakami at Fondation Cartier; and the opening of museums by private collectors such as Eli Broad and François Pinault and his Venetian Palazzo Grassi-these all feed back into this phenomenon.

FROM PSEUDO-EVENTS TO GOSSIP EVENTS TO REALITY TV

Furthermore, these events have assumed the strange air of Daniel J. Boorstin’s “pseudo-events”: activities that exist for the sole purpose of media publicity and become “real” only after being viewed through news, television, and now, I add, social media.4 The concept was coined in 1962. Boorstin explains that “pseudo-events” are dramatic, planned, repeatable, costly, intellectual and social, adding further that one must know about it to be considered “informed.” It also enables a connection with Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics, an art that takes as theoretical framework the sphere of human interactions and its social context: live experience and the importance of the opening and the idea of seeing something and discussing it at the same time.5

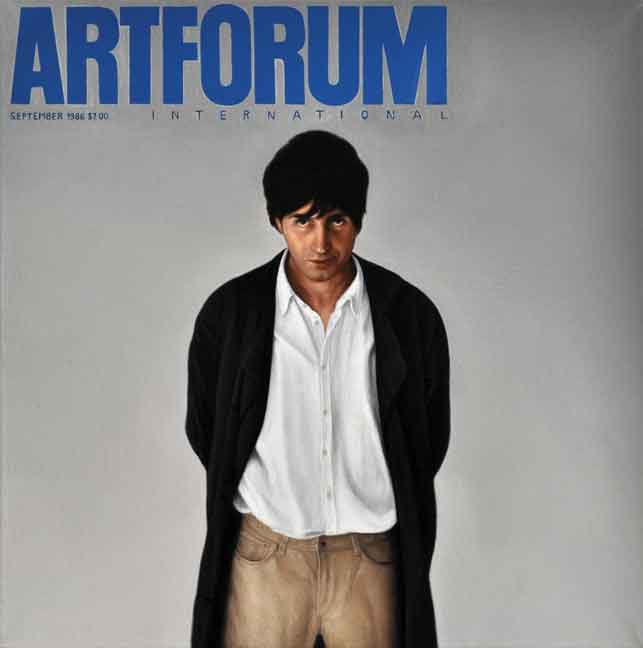

Forty years have passed, and pseudo-events have transformed into “gossip events”: Artforum’s Scene and Herd. “Justine Koons, Jeff’s wife,” writes Sarah Thorton, “and mother of five of his seven kids, is in the next room. Pregnant with her sixth and his eighth child (a boy, due in August), she walks past Balloon Venus, another new sculpture, giving it a cursory glance. [...] The sight of an expectant spouse between two Venuses evokes one of Koons’ many mantras: ‘The only true narrative is the biological narrative.’”6 Celebrity journalism is devoid of any critical or aesthetic value, reporting on those who are considered to be a “celeb” and whose roamings serve as “serious gossip” for the art readers who can continue building their own fictions of intimacy. It’s the who-is-who of the art world packaged not as simply and banally as tabloid gossip, but much more in the sense of a secret meaning to be shared by insiders, id est, its readers. Artforum has made reading/seeing gossip a buzz: you have to pay attention to it. “Psssst, it’s important!”7

Notoriety, ownership, and exclusivity are part of the materialistic approach of a society in which money is seen as a primary indicator of life. Thus, many new collectors, like bankers, hedge-fund managers and real estate companies, have become the driving purchase force of the art world since the end of the 1990s. “There is also a surprising similarity,” writes Klaus Honnef, “between works of art and many financial instruments in that both are wholly devoid of any corresponding real value. Works of art are artificial constructs whose material elements are generally of little value and whose prestige depends entirely on agreement between specific social groups assigned a trend-setting role, which the art industry beguiles and invites to participate in the world of the art, even if not to actually to be part of it.”(146-147) Among Artforum’s art critic’s picks, Artforum’s The Best of 2012, Artreview’s Power 100, Flash Art‘s Top 100 Artists, The Artnews 200 top Collector’s List, Artfact’s Artist Ranking List, Germany’s Kunst Kompass Ranking, Phaidon’s CREAM, TASCHEN’s Art Now and Art at the End of the Millennium, Christie’s and Sotheby’s breaking records, museums’ increasing number of visitors-this mix of gossip, idle talk, diffused celebrity and economic criteria stimulate social hierarchies much in the tradition of financial and economic market trends.

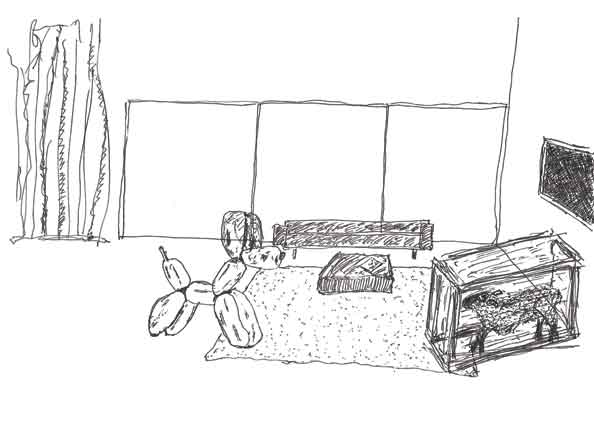

Motu Christian Steyrl, Un portrait de 'la carte et le territoire’ - page 007, 2011, pigment pen on paper, 8.26” x 11.7”. Courtesy of the artist.

Finally, an element that I wouldn’t like to leave unsaid within this reign of gossip and celebrity is reality TV’s emergence within the premises of the art world. Yes, you’re right: I’m talking about Work of Art; The Next Great Artist, with the participation of judges such as Simon de Pury, China Chow, Bill Powers and Jerry Saltz.

Fourteen artists from all around the world enter in a competition in order to create the big work of art and earn $100,000, a solo exhibition and become the next great artist. As de Pury says, “Reality TV is a fantastic opportunity for an artist to get noticed.”8 Big Brother may come up immediately as the logical example of a program that, according to Jonathan Bignell, “offers a voyeuristic gaze to its viewers and promotes exhibitionism in its participants and [...] it might represent a new kind of access to, and interest in, ordinary people on television that can air important issues about identity and community in contemporary society.”(Bignell 4) Nevertheless, the art world had done it a little before: Josh Harris created an artificial society in an underground bunker in New York City where approximately 150 artists moved into at the end of 1999; the participants in QUIET: We Live In Public were under 24-hour surveillance and on camera while they defecated, had sex and even shared a transparent communal shower. The city authorities soon raided the building on the morning of January 1, 2000. “Ordinary people” have given way to “ordinary artists” in this case.9

Since then, with Wife Swap, The Osbournes, The Real World, Jersey Shore to the most recent Quiero ser torero (I Want to Be a Bullfighter) and the futuristic Mars One,10 reality TV fought back against the expansion of capitalism’s ideology of individualism from old media to social media. Both reality TV and social media play with the production and the presentation of the self. Social media and the art world engage more and more, and it also affects art and arts writing in many ways.

FROM MASS TO SOCIAL MEDIA

Very much like our society at large, in which the borders between private and public have been erased. “The product [the people] are willing to promote and sell on the market is none other than themselves,” says Zygmunt Bauman. “They are, simultaneously, the product promoters and the product being promoted. They are in charge of marketing and merchandise, traveling salesmen and an item for sale, all at the same time.”(17)

Television brought the stars into our homes, and now social media enables us to go into anybody’s home (screen). It is easier today than ever before to become a celebrity, as there are more outlets than ever-reality TV, YouTube, Myspace.com, Vimeo, Facebook, Twitter, blogs-and less talent required. The “ordinary citizen” or “girl/boy-next-door” can attain her/his dream celebrity as humble subject in what has to be understood as a perverse role in consumer society’s manipulation of celebrity to maintain the image of democracy. Social media represent the total democratization of celebrity. As such, celebrity has taken on an air of vulgarity, and anybody can be notorious for no particular reason.

But let’s finish like we started, id est, quoting one of the biggest art celebrities: “I’ve always had a conflict because I’m shy and yet I like to take up a lot of personal space. Mom always said, ‘Don’t be pushy, but let everybody know you’re around.’”(Warhol 146-147) Social media now are the perfect tribute to and embodiment of the Warholian idea of commanding space, and it seems that art is more about celebrity and less about art itself.

WORKS CITED

- Bauman, Zygmunt. Vida de consumo. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica de España, 2007. (English version: Consuming Life, Cambridge: Polito Press, 2007).

- Bignell, Jonathan. Big Brother. Reality TV in the Twenty-First Century, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Honnef, Klaus. “Critics of Contemporary Art”. The Art of the 20th Century. 2000 and Beyond. Milano: Skira Editore, 2009.

- Moran, Joe. “The Reign of Hype. The Contemporary (literally) Star System”, in P. David Marshall (ed.), The Celebrity Culture Reader, New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Warhol, Andy. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. Boston: Mariner Books, 1977.

NOTES

1. The ignorance is so widespread that even Isabelle Graw, art historian and founder of Texte zur Kunst, author of High Price. Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture, confounds both terms, which is rather weird considering it’s the main topic of her book. Furthermore, Mrs. Graw displays the typical intellectual disdain towards celebrity culture, as among her bibliography there are hardly three books on this topic to which she refers. It’s a pity, because the book explores the futile dichotomy of art and market in a fruitful manner, but I find this attitude incomprehensible and intellectually irresponsable.

2. See, David Giles, Illusions of Immortality. A Psychology of Fame and Celebrity. London: Macmillan Press, 2000, pp. 3-11.

3. See Leo Braudy, The Frenzy of Renown: Fame and its History. New York: Vintage Books, 1997.

4. Daniel Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. New York: Harper and Row, 1962.

5. See introduction to Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002, pp. 7-24.

6. See <http://artforum.com/diary/id=31282> (accessed 24 June, 2012). Sarah Thorton is, by the way, a leading figure of this kind of celebrity journalism, and her Seven Days in the Art World is a perfect example of this trend.

7. Another less cool website is Guest of a Guest, which promises to “make the community members celebrities.”

8. See, <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MGwjDhRhtVg&feature=player_embedded> (accessed 24 June, 2012.)

9. While I’m writing this article, the new Bravo TV reality show Gallery Girls, who are wearing stilettos and makeup, is promoted as “The Cutthroat World of Gallery Girls.”

10. The reality Show Mars One is supposed to kick off in the year 2026. This idea has been conceived by Dutch businessman Bas Lansdorp, who wants to secure private money for scientific research by making reality TV on Mars. It would be a permanent colony on the red planet, with the singularity that the chosen candidates will never return.

Paco Barragán is an independent curator and arts writer based in Madrid. He is curatorial advisor to the Artist Pension Trust in New York. He recently curated “The End of History…and the Return of History Painting” (MMKA, The Netherlands, 2011) and “¡Patria o Libertad!” (COBRA Museum, Amsterdam, 2011). He is co-editor of When a Painting Moves…Something Must Be Rotten! (2011) and the author of The Art Fair Age (2008), both published by CHARTA.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.