« Editor's Picks, Features

From ZERO to Now. An Interview with Heinz Mack

![1-sw-17001-der-garten-eden Heinz Mack, Der Garten Eden [Chromatische Konstellation] (The Garden of Eden [Chromatic Constellation]), 2011, acrylic on canvas, 143” x 236.” All images are courtesy of the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.](http://artpulsemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1-sw-17001-der-garten-eden.jpg)

Heinz Mack, Der Garten Eden (Chromatische Konstellation) (The Garden of Eden (Chromatic Constellation), 2011, acrylic on canvas, 143” x 236.” All images are courtesy of the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

One of the co-founders of the influential ZERO group, Heinz Mack was already making avant-garde art when he and Otto Piene organized the first ZERO art show in 1957. Born in Germany in 1931, Mack attended the art academy in Düsseldorf in the 1950s and also earned a degree in philosophy from the University of Cologne. Reacting to the more expressive nature of Tachisme and Art Informel (the dominant abstract art movements in Europe during the 1940s and 1950s), the ZERO artists embraced the use of light and motion to engage new forms of perception, where science and technology took center stage.

Mack, Piene and Günther Uecker, who joined the group in 1960, produced publications and exhibitions that brought together like-minded artists making reductive art. The name ZERO, itself, referred to the countdown to the launch of a rocket, which was considered a means to reach a new place, a new beginning-a conceptual “ground zero.” ARTPULSE contributor Paul Laster recently sat down with Mack at Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York and the AXA Art Lounge at TEFAF in Maastricht to discuss his fascinating art and life, which have become inseparable.

By Paul Laster

Paul Laster - Having been born in Düsseldorf in 1931, what do you remember of the Second World War?

Heinz Mack - It’s still a part of my life. At the end of the war I was 14 years old. I experienced the bombing of the city when 2,800 people were killed in one night and many more were wounded. I had a small Agfa camera and made some photos of the night sky lit with searchlights, and 20 years later I made a drawing that surprised me because it strangely resembled my photo from that night. The sky was lit up like fireworks. I had forgotten about how dangerous it was to be out because I was completely fascinated by this wonderful light. Light means a lot to me-to my life and to my art. In the right situation it can look immaterial. Color deserves to be as rich as possible in light, too, so that it can be its most radiant.

P.L. - What kind of art scene rose from the ashes after the war?

H.M. - There was a certain kind of emptiness, of poorness. We were totally poor in information. We didn’t know what had happened in art during and even before the war. I was quite young when I entered the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1950. I was just 19 years old, but I was eager to learn. There were only two books in the library. Everything else had been burned or was gone. There was this emptiness, which was a big handicap on one side, while on the other side-by being completely alone-you had to find your own way. You had to discover what was inside yourself before you looked into books. The best artists-such as Paul Klee, who had taught at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf before the war-had been fired and fled or were sent to the concentration camps.

Heinz Mack, The Sky Over Nine Columns, 2014. Sakip Sabanci Museum Istanbul, 2015, Private Collection. Courtesy Beck & Eggeling International Fine Art. Photo: Murat Germen. This installation is a project by the Ralph Dommermuth Foundation for Art and Culture, which is managed by Beck & Eggeling International Fine Art.

P.L. - What was your motivation for founding ZERO?

H.M. - We had been very influenced by the Ecole de Paris [School of Paris] and Art Informel. In 1957, I was painting like a wild beast and unexpectedly ran into a deep crisis. I stopped everything and tried to forget what I had learned. I wanted to start at the beginning as simple, as poor and as clean as possible. At the same time, man was starting to journey into outer space. It was an exciting time, a time of evolution. Artists from other countries embraced us. For instance, when I was in New York in the 1960s, I had serious discussions with Barnett Newman. In New York, they asked me what was happening in Europe, and in Europe, they wanted to know what was going on in New York. Information traveled very slowly, whereas now there is too much of it.

P.L. - Was there a manifesto for ZERO?

H.M. - Yes, there was a typewritten text. The title of the essay, or manifestation, was “The New Dynamic Structure.” Structure means a lot to me because I personally decided to give up the idea of composition and the principle of three-dimensional perspective, which had ruled the art world for more than 600 years-starting with Giotto and ending up with the Cubism of Picasso, who radically destroyed the notion of composition. Picasso replaced the principle of composition with structure. All of the ZERO artists were concerned with structure. It was very important. It was the key. Now we have researchers studying nature with microscopes discovering that nature consists of structures, like fractals. And it goes along with music, such as the compositions of Philip Glass, Terry Riley and Steve Reich. I started with these ideas in 1958.

P.L. - How quickly did the movement grow?

H.M. - Somehow like an explosion. It was a kind of awakening. Before, we had all been alone, and we felt lonely. I was a lone wolf in my studio. No one was looking at me. Then all of a sudden other artists came up and said, “What you are doing is very exciting, because I am having similar ideas.” It turned into a beautiful kind of friendship, with cooperation and discussion between artists, even older ones like Lucio Fontana-he could have been my father-while others like Jan Schoonhoven were quite young. Fontana said, “I feel as young as you are.” Then in Japan, I met Jirô Yoshihara, who was a kind of Japanese version of Fontana. He was one of the founders of the Gutai group. There was a spiritual relationship between our movements, which led to a lot of shows that were created under quite difficult conditions, without money.

P.L. - How did the lack of money impact you?

H.M. - When I made my film in the desert, our budget was ridiculous. We had to keep track of the number of bananas and oranges each member of the team received as food. There was no money. Film was very expensive. I’ll never forget the time when the light was magnificent on my sculptures. There was a sunset and a kind of mirage. It was like a Fata Morgana [a mirage], and I cried to the cameraman, “Shoot, shoot, shoot,” and he kept still and said that he didn’t have any more film. There was nothing we could do. Compared to the American Land artists, who had the collector and art dealer Virginia Dwan supporting them, it was a struggle for me to do what I could do.

![3-sw-17018-white-vibration Heinz Mack, Weisse Vibration [White Vibration], 1958, synthetic resin on cardboard on wood, 55 ½” x 39 ¾.”](http://artpulsemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/3-sw-17018-white-vibration.jpg)

Heinz Mack, Weisse Vibration (White Vibration), 1958, synthetic resin on cardboard on wood, 55 ½” x 39 ¾.”

P.L. - Did you exhibit with the Land artists, or was that more of an American art scene?

H.M. - No, but there was a big show of Land art in Los Angeles at the Museum of Contemporary Art ["Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974"] a few years ago, and I was finally included. Through research it was determined that I had conceived my “Sahara Project” before the Americans, which makes me very proud.

P.L. - Did you ever make figurative work?

H.M. - At the academy, of course, but I didn’t show it, and only one other time for a church. The church had been destroyed in the war and the priest was interested in modern art and asked me to do it. It was an exception to my other work, but I wanted to make a spiritual space-a space that had a certain sacred nature to it. I was uncertain if I could do it, but I was successful with it.

P.L. - What was the appeal of abstraction, which was the path you chose?

H.M. - It’s an interesting question, but a very difficult one to answer. For the most part, my work has been non-figurative. Nevertheless, I sometimes feel that my work goes along with nature, but in the dimension of structures. Not far from where I live is a research center where scientists and professors study nature, and when I visited there I saw that my work was very similar to the structures they research. They don’t have an explanation for it, but I’m impressed by their work, and mine impresses them. Leonardo da Vinci famously stated, “Study the science of art. Study the art of science.”

P.L. - Do you think ZERO had an impact on Minimalism?

H.M. - Yes and no, because in the beginning we had the idea to make things as simple as possible-to reduce everything to its essence. From time to time, I’m a piano player and I used to always play with two hands. But then I had the idea to only play it with one finger and one toe-to forget whatever I had already learned. As soon as I realized that a number of artists were concentrated on Minimalism I refused to follow them, because I dislike dogma, and they had become dogmatic. Art is far too rich in ideas and fascination. I’m not just a mathematician who is solving problems. I like things that end up incorrect.

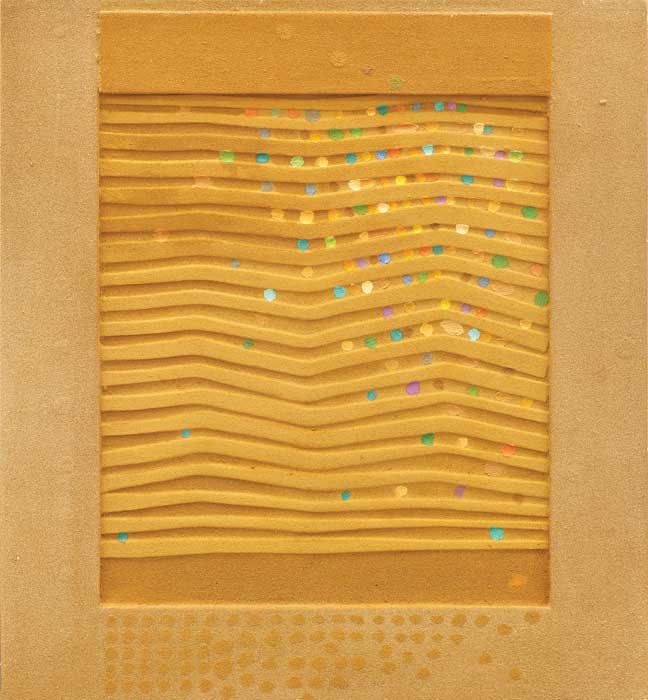

Heinz Mack, Sand-Relief, 1967, sand and pigment on masonite board, Plexiglas box, 39 ½” x 35 5/8” x 3.”

P.L. - Do you think the minimalists were looking at what you guys were doing? We know that they were looking at the Russian avant-garde.

H.M. - The Russians had such a strong anticipation of what was to come, but even Kazimir Malevich with his Suprematist work was constructing compositions. It goes along with the old world of composition, but if you look at the last paintings of Piet Mondrian-paintings like Broadway Boogie Woogie-it’s already a structure. Jackson Pollock was structure, too. He destroyed composition.

P.L. - What was the New York art world like when you lived here in the 1960s?

H.M. - It was a small world, which was dominated by Leo Castelli and Sidney Janis. Abstract Expressionism was still popular, but after my experience with World War II, I was against expressionism. The whole German art scene that followed-like Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer-was completely expressionistic. They forgot about the Bauhaus, which was another dimension of German art.

P.L. - Were you still painting when you were living in New York?

H.M. - No, I was making reliefs and sculptures, which were steles. I had a solo exhibition in 1966 at the Howard Wise Gallery with my steles, which were somewhat of a reflection on Manhattan, with its skyscrapers. It was a very important show for me, and some of the pieces were moving. Wise was the only one involved with kinetic art at the time.

P.L. - Why had you stopped painting?

H.M. - That’s an interesting question. After 10 years of making paintings during my ZERO time, I felt that this ZERO idea should not become an institution, because each artist needed to pursue his own work. We had to follow our own ideas, which didn’t always relate to those of the other members of the group. In the end, I hated the idea of being part of a group, and together with Uecker-he was on my side-we spontaneously told Piene that we had done what we could do over the past 10 years and that we should stop it. We didn’t want to become a family with relatives.

P.L. - Like The Beatles…

H.M. - Exactly, and Piene felt just the opposite. He told us ZERO would stay forever. Even when he became 90 years old-and up until he died-he was still proclaiming ZERO never stopped. But it had stopped in 1967 and my new work started.

P.L. - When did you start using industrial materials?

H.M. - That was very early on. I always used traditional tools that had been used for centuries. That was one point of view, and at the same time the world was starting to become more technological. It was the time when man started to go to the moon. I happened to discover a new material in a shop on the Bowery in New York. This new material was honeycomb aluminum, which is an American product that’s used in the aerospace industry. I was interested in this material for its relationship to Goethe’s botanical work and morphological nets in nature.

P.L.- Thinking about man going to the moon makes me want to ask what took you to the desert.

H.M. - I had this desire to discover something that had never been seen by anyone else. It was also a question that took control of my heart and my brain: How can I discover a new space? The space that was in museums or galleries was not the space that I was dreaming of, that I was longing for. I wanted to find a new space, because I wanted to experience and discover how a new kind of space would envelop my sculptures. How would that space react to my sculptures? Is there an interaction between my sculptures and the space? This endless space, this enormous dimension without any borders and without any civilization or any fingerprint of civilization-I was seeking a very pure, untouched landscape. If I put a piece of mine in this space, in this landscape, what would happen? This was a big matter of researching and experiment and adventures. Whatever you do in the desert, the light around it has such intensity. Sculptures get a new dimension from this light. The proportions and dimension of the sculptures cannot be estimated and controlled by meters anymore, and without any meter measurement the work becomes more immaterial. This condition of light and space were tested in my first experiments in the desert. It was very fascinating.

I was the first European artist to get involved with Land art. All of these experiments and expeditions to a very strange world-without any kind of tourism-were unknown in those days. It was a big adventure, which made me realize that my sculptures appeared in this landscape like instruments of light. They became immaterial and at the same time luminous through their materiality. In a religious sense, it was a kind of epiphany. There was an explosion of light.

P.L. - Are those the ideas that you are still exploring with The Sky Over Nine Columns, the monumental sculpture that you have exhibited in Venice, Istanbul and St. Moritz over the past few years?

H.M. - It’s still belonging to this area and, of course, I would like to have it in the desert instead of spaces in Europe, but that means a lot of money. It was in Spain before it was shipped to Switzerland, which meant $300,000 to $400,000 just for shipping. The same thing happened to Christo, who spent his own money on his projects, but now he’s given up. I think that was the right decision. Now everything is spoiled by tourism, which is another reason why it’s difficult. There’s almost no space left for the arts-wherever you go it’s just tourists, tourists, tourists!

Paul Laster is a writer, editor, independent curator, artist and lecturer. He is a New York desk editor at ArtAsiaPacific and a contributing editor at Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art and artBahrain. He is a contributing writer to ARTPULSE, Time Out New York, The New York Observer, Modern Painters, Cultured Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, Galerie Magazine and Conceptual Fine Arts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.