« Features

Gustavo Acosta: Paper Trails

Known for his peculiar urban renderings as representations of symbols of power, Gustavo Acosta (Havana, 1958) has based his work on the social and political aspects that architecture represents. He talked to ARTPULSE about what has influenced him through the years, how he dissects his surroundings with an almost cinematographic eye, and how he approaches art as a consequence. His current exhibition, “Paper Trails,” becomes an excellent example of different elements from all his production, making visible all the trajectories we identified in his current work.

Known for his peculiar urban renderings as representations of symbols of power, Gustavo Acosta (Havana, 1958) has based his work on the social and political aspects that architecture represents. He talked to ARTPULSE about what has influenced him through the years, how he dissects his surroundings with an almost cinematographic eye, and how he approaches art as a consequence. His current exhibition, “Paper Trails,” becomes an excellent example of different elements from all his production, making visible all the trajectories we identified in his current work.

By Irina Leyva-Pérez

Irina Leyva-Pérez - Since the beginning of your career, you have been interested in illustrating the symbols of power through urban scenes. In your early works you utilized Roman referents as metaphors for the political situation in Cuba. Are you still using this relationship of power through architecture as a theme in your most recent work?

Gustavo Acosta - The inevitable link with power in a reality like the Cuban one is omnipresent; for some of us it is toxic and we react to it in different ways. I turned it into the focus of socio-aesthetic discourse that moved away from the supposed utopian positivity, from the longed for “bright future” that communism promised. I tried to make the symbolic look at imperial Roman history function, firstly as a protective cloak before the mediocre censorship that was incapable of reading between the lines, and secondly, for those who wished to look for it, a kind of magic mirror that would mercilessly unleash the truth in our faces.

My recent work, without being totally separated from ‘Cuban affairs,’ is still lecturing from architectural and urban spaces and from the relationships that citizen collectives establish with the powers through these. When you live in a totalitarian system, you confront a power; when you manage to escape to the real world, you discover that there are powers everywhere.

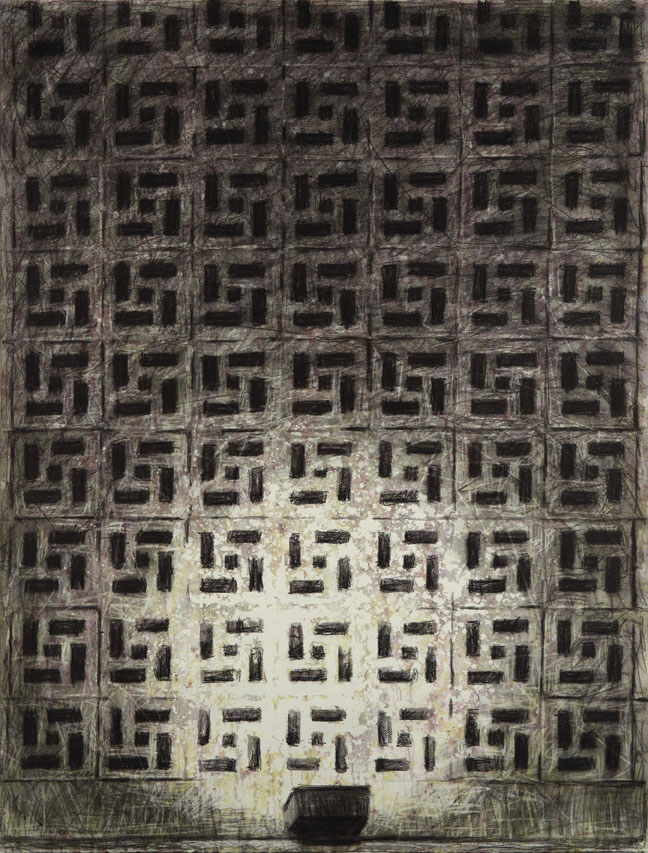

I.L.P. - You utilize as a starting point for your works photographs that you take of different places, but also images that you gather from the media, which makes your work become a kind of pulse of the social situation. I refer to pieces like Holy Land. What is your intention in using these images?

G.A. - All of this started with the exhibition “Los Juegos del Príncipe” at the Galería Nina Menocal in Mexico City in 2006. For two decades I had been working on symbolic terminology, very loaded by the experience of the last years lived within Cuba and the first few outside. In “Los Juegos del Príncipe,” I went back to using photography as reference and essential documentation, but in contrast to previous experiences in which I attempted to rediscover or relate in another way the history of a specific place that was Cuba, where information was received in dribs and drabs and usually very dull; suddenly I confronted a phenomenon that was like an eruption, an avalanche soon enhanced by digital media, the Internet. In turn, the world was changing, the natural disasters, the accidents, the terrorism, the wars. I could not be indifferent to all of this; I devoted myself to working with sensational news that disappeared almost as soon as it appeared, immediately making way for more. “Holy Land” was a series of drawings in which I commented on the drama that the aforementioned situations could signify for each nation or individual, regardless of culture, religion or importance in the global structure.

I.L.P. - Your work has as a central theme cities that you seemingly illustrate from the perspective of a passive observer. However, except on rare occasions, you do not include the inhabitants, the human beings. Is there a reason for this exclusion?

G.A. - Many years ago as a student in San Alejandro, and I can picture the scene in my mind, two friends and I were leafing through a book and the work Early Sunday Morning by Edward Hopper appeared. For the three of us it was like finding the Holy Grail. That strange realist work, frontal, almost geometric, suddenly offered surreal readings, very difficult to classify or define in the principal tendencies of artistic movements of its time; I found this very attractive. The title itself, for those of us who were trying to escape from the lyrical excesses of Cuban art at the time, was revealing, an epiphany.

The effect was not immediate, but years later, in the first drawings and paintings that I was able to exhibit, the echo of that afternoon was present. Hopper, along with other diverse experiences, allowed me to create a cosmos in which constructions and other urban elements are expressed as characters, a theatricality, a mirror (again) of humanity that never ceases to seduce me.

I.L.P. - Some of your works are aerial views in which an omnipresent gaze is implied, as in The Doors of Perception, or Let Me Tell You About My Last Dream. The Doors of Perception is also the title of the famous book by Aldous Huxley that inspired a whole beatnik generation. Is there a relationship between this work and the manner in which Huxley proposes exploring the reality that we see on a daily basis? What inspired you to create these pieces?

G.A. - Let us return to the exhibition “Los Juegos del Príncipe.” It consisted of various series: One of them was “The Stalker.” With these works I set out to enter forbidden places, just as institutions and governments do, or like a criminal or ecological activist or someone in his own house with the heightened security with which we live. The work The Doors of Perception, whose title I took from Huxley, comes from a piece in the aforementioned series “Stalker” and was the beginning of another long series of nocturnal aerial images of urban concentrations that I called “Códigos Secretos.” Those concentrations of lights and the designs they generate always hypnotize me when I fly at night, and to me they feel like communications systems of unknown origin, as though new and for us indecipherable symbols like those in the Nazca’s valley were imperceptibly being generated by our cities-yes, a little paranoia and psychedelia.

Over time, these works turned into diurnal images and the viewer grew closer to the subject. The reality represented acquired a sense of place and referred to specific sites. In the projects I am still working on, I take this type of work in another contextual direction.

I.L.P. - A couple of years ago you did a series of paintings in which the color green predominated, like images seen through night vision goggles, and you entitled it Under Surveillance. Tell us a little about the background of these pieces.

G.A. - It is another byproduct of the series “Stalker” with the ‘tech’ quality of the nighttime surveillance images and their characteristic green color. I have always enjoyed using paint to imitate qualities from other media: filmic, photographic. At the beginning of my career it was colonial graphics, maps, vintage photos, all of that dirty, scratched and moth-eaten world. Later on, I began to observe the solutions of graphic novel illustrators, architects and designers, from whom I have learned, and how I resolve things comes more from them than from the visual arts that we certify as being traditional or legitimate.

I.L.P. - Sometimes you select functional parts of cities that pass by unnoticed, and that may seem uninteresting, like parking lots, as in El Mundo de Dade. What is it that you find attractive about them?

G.A. - It is another approximation to Hopper, of course, interacting with many other influences, and also there are the spaces that I have been leaving blank and then I return to them. I always try to avoid ‘important locations,’ and in this I approximate, even in the terminology, the movies. It is narrating utilizing what passes by unnoticed, the hidden history of these indispensable but insignificant and even ugly places. It is a type of theme that I began to approach more when the city of Miami started to enter into my equation. I have always felt a morbid curiosity for the rejection and the gravitational pull that this city appears to generate at the same time.

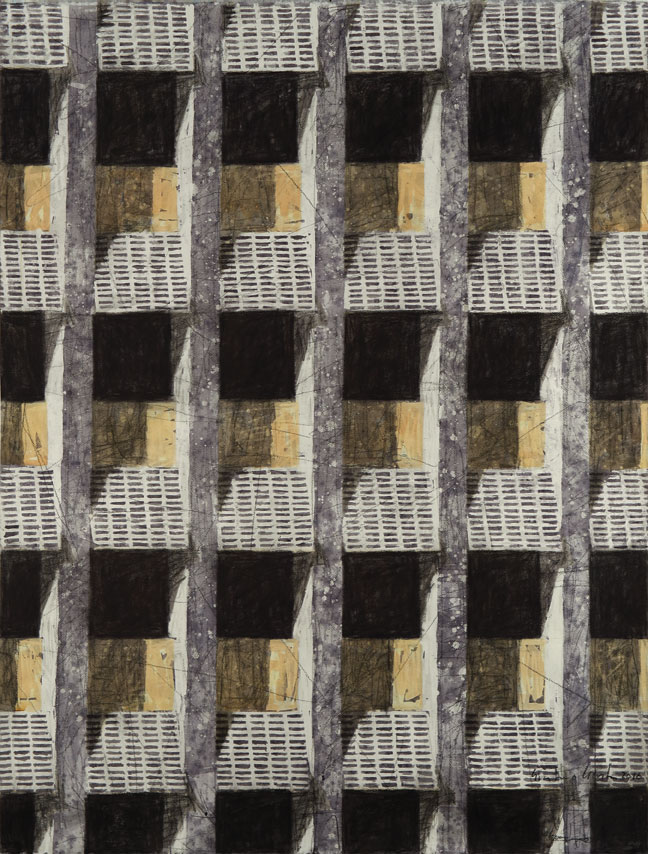

I.L.P. - Much of your recent work has been concentrated more on architectural details as isolated elements than on the urban scenes that characterize it. I refer to fragments of windows or latticework, which you have taken out of context and present isolated like a close up, resulting in almost abstract images. Is this an essentially aesthetic exploration?

G.A. - It is difficult for me to be at peace in one line of work. Recently, I have been working on large-format works, very time consuming, that honestly leave me exhausted. When that happens the solution is not to create small paintings, but instead I almost always start drawing, and usually something different. For example, a couple of years ago it was drawings in blue ink, with the characteristics you are talking about. Those drawings generated the recent series of paintings, and now I am drawing again, large works, polyptychs on paper product that a short time ago, at a retrospective exhibition in Brazil, I had in front of my work from the 1980s, when I had to invent solutions to be able to create large works without adequate resources. Yes, they are aesthetic solutions, but inherent to the method of documentary or cinematographic dissection with which I try to examine the matter at hand from all possible angles.

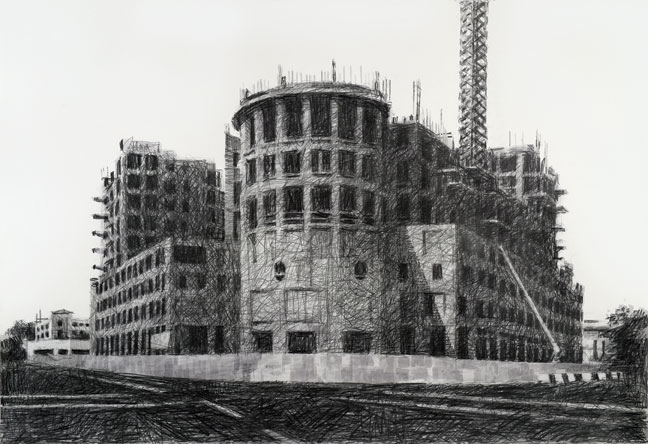

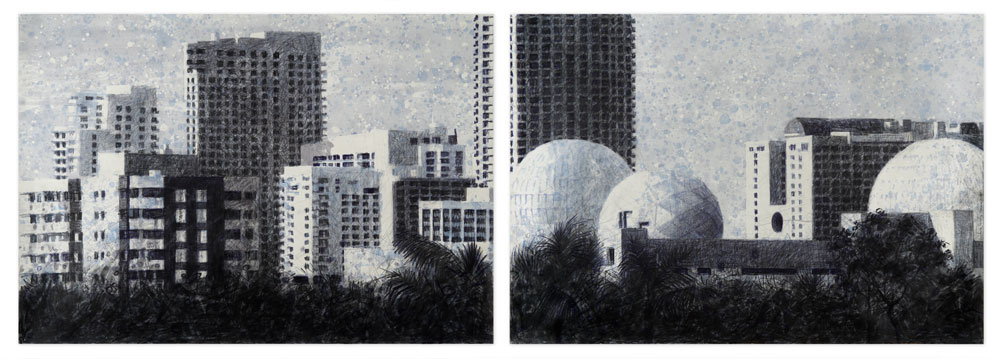

I.L.P. - You have illustrated the accelerated process of ‘gentrification’ that has transformed the city of Miami at a rapid pace. By documenting buildings under construction, as in One Day I will Build Myself a Circus, or the transformation of a corner, as in Estampida, or in The Book of Hours, you become a kind of chronicler of the city. How, when and why did you start becoming interested in documenting these changes?

G.A. - I mentioned this before. The opportunity to live in worlds as different as Cuba, Mexico and Spain, and now, for 21 years, Miami, has been most interesting. I cannot be indifferent to the place in which I live, and this city, like any other, is full of big and small stories; of course, the interpretation depends on the reader and how he wishes to interpret it. For me, the interesting thing about any city is that they are live organisms, where one story ends, another begins at an unrelenting pace. Physically speaking, sometimes it is hard to tell if a work is an act of construction or demolition. Sometimes demolitions hurt and constructions make us angry, but along the way, we become emotionally attached to the place that, with all of its pros and cons, we call home.

One Day I Find Myself Building a Circus is a work of indignation about budgetary excesses in the construction of the city’s baseball stadium. In the end the result was beautiful. We have a great stadium, but I am pleased to have disagreed with the procedures. The opposite happened to me with the old Miami Herald building. For me, it was like demolishing a cathedral to literally make way for a casino that was not constructed after all.

I.L.P. - Some time ago, the most influential collectors favored the acquisition of installations and other media like video art more than paintings. Many bet that painting as a genre would disappear. However, just the opposite has happened. What do you think of the new interest that exists in painting as a manifestation?

G.A. - I must digress and say that thanks to a sector of the market that appreciates my work, I have arrived at where I am today, but that is by far not a rule that applies to many good artists. I have been hearing the same damned bad omen since art history class. I found out that almost a century before, and systematically, declarations of all kinds condemned painting to death to create other painting, until, of course, Duchamp arrived, who, more than dirty work, preferred to play chess. Those of us who have not renounced the ministry of confronting on a daily basis the canvas, the pigments, the silent dialogue that is established in the studios and the act of magic that creation signifies shall not renounce it, because it might occur to someone that one of the first acts of magic that has been with us since the caves no longer has a reason to exist.

Gustavo Acosta, TMH, 2016, mixed media on paper, 45" x 34." All images are courtesy of the artist and Pan American Art Projects Miami.

I believe that painting does not die, nor does the current interest in it grow. I agree that if one could quantify it, a high percentage of painting is dispensable and it has always been so. However, to claim that the same thing does not happen with other manifestations of contemporary art is to attempt to cover the sun with a finger. The selection of a medium or material is not an excuse to legitimize one artistic expression over another or to consider it obsolete, nor do I say that ‘painting’ is contemporary art; it is part of it.

Institutions and the complicated system of legitimizing art have been responsible for this simplification, but so has ignorance. I have had the opportunity to see transactions with works of art, whose counseling service was akin to that used to buy coal shares in the stock market that ended up with checks in enormous amounts and everyone very happy drinking champagne and the work there in its little corner without anyone having a good understanding beyond the promised profit, of the reason for the acquisition, if it was good or bad, if it was liked or not. The work itself was definitely unimportant.

For those of us who paint, it is stimulating to see how in certain geographic areas pictorial and sculptural creation is respected and honored, that in some way it is maintained in a certain traditional structure. It is an example of the sometimes formidable support of markets and institutions and in moments of crisis and doubts about art as in current times, artists fortunate enough to belong to or live sheltered by these nations begin to enjoy great visibility. Look, in contrast to the radical period of the avant-garde, when the cooks who flipped the tortillas were the artists themselves, artists who really shocked and literally risked their lives, like the Russians; today almost everything smells of market. The market kills one way of acting because it suits it and then resuscitates it for the very same reason.

As far as we are concerned, let us hope that the renewed interest arrives soon, rubs off on those of us who have not given up and surprises us working.

Irina Leyva-Pérez is an art historian, art critic and curator based in Miami. She has lectured at Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts and was assistant curator at the National Gallery of Jamaica. She is currently the curator of Pan American Art Projects, a regular contributor to numerous publications and author of catalogues of such Latin American artists as León Ferrari, Luis Cruz Azaceta and Carlos Estévez.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.