« Editor's Picks, Features

Interview with Carolee Schneemann

“I began to motorize paintings in my constructions because men hadn’t done that.”

“I began to motorize paintings in my constructions because men hadn’t done that.”

I’ve had this interview on my mind now for several years, and to be able to conduct it at this time is opportune, especially nowadays, with the way that history seems to be repeating itself. Caroline Schneemann’s work is relevant to current events, in the same way that it was during the important political changes that took place during the 1960s and ‘70s. Her contribution to the empowerment of women in art and her endless motivation and persistence has left a valuable legacy to the younger generation of female artists.

BY LARA PAN

Lara Pan - Carolee, you started your career as a painter during a time period when not many women artists had access to go to college and receive an art education.

Carolee Schneemann - I don’t consider it a career. I consider it a process, a calling. I used to draw obsessively when I was four years old, and there was some aspect of the necessity to realize images that was innate. It was always there for me. So by the time I wanted to understand what an artist was I was told that it was wasteful for a young woman-for a girl-and my dad, who was inspiring to me, refused to send me to college.

L.P. - Once you got the scholarship to Bard College, I assume it was very difficult to be one of the rare women artists at that time.

C.S. - Once there I was told by my painting teacher, ‘Don’t set your heart on art, you’re only a girl.’ So the history of my work is this collision with a double message: You can try what you need to do, you’re gifted, but don’t expect to have any authority or any self-realization. But you can do it, it doesn’t matter, nobody’s going to care. I had a few teachers who did care, and they were actually unique for me in their appreciation and their regard. So that helped me along.

L.P. - Besides being a painter, you have shown a great ability in working with so many different mediums. Do you think that the use of so many mediums could create obstacles? Not many men or women artists, in my opinion, have been successful in manipulating diverse mediums in their artistic career.

C.S. - As a painter, I had access to what I wanted to use. But when changing mediums, critics would say, ‘You’re all over the place.’ A male artist could move from performance to installation…and was always permitted. As a female artist I had to have an identifying brand. Changing mediums wasn’t forward; it was confusing and degrading.

Carolee Schneemann, Flange 6rpm, 2011-13, installation view, foundry poured aluminum sculptures, motors 6 rpm each unit, 7 units, 9’ x 20’ x 3.’ Courtesy of P.P.O.W. Photo: Susan Alzner.

L.P. - Your creative process is very connected to a scientific way of thinking and scientific research. Can you tell me about your relationship to science and nature?

C.S. - I was largely influenced by D’Arcy Thompson and the connection into visual morphology. My interests were also in the variation and potentiality of material, even printing processes, the juxtaposition between electronic and virtual material. Those were all areas where I wanted to develop my visual vocabulary. So going to film seemed like a natural exploration and extension of abstract expressionism and to activate visuality frame by frame. And then it also had a musicality as energy extended into time. And, of course, that was a continuous influence by my partnership with James Tenney and his [interest in] computer generated sounds. They extended my sense of collage and visual dynamic (projection systems).

MIRRORS, PAINTING AND THE MASCULINE

L.P. - One thing that interests me about your art is your way of using mirrors in your work. Is this a reflection on ‘the space in between?’ I can’t help but think about some of the use of mirrors in the works of your colleagues such as Hans Breder and Ana Mendieta. Why mirrors? Can you tell me more about that?

C.S. - My mirrors began with my painting constructions. I wanted to insert part of the environment within the collage, but when people looked at it they used to think I put mirrors so that I could look at myself, which was extremely offensive and stupid. But it was so that they would see themselves within this phase of their conceptual proportion. The mirror is very exciting, and to have a motorized mirror that can take part of the environment that’s painted or constructed and move it around the space is just a very enriching kinetic dynamic. I don’t think I was influenced by anyone else using mirrors.

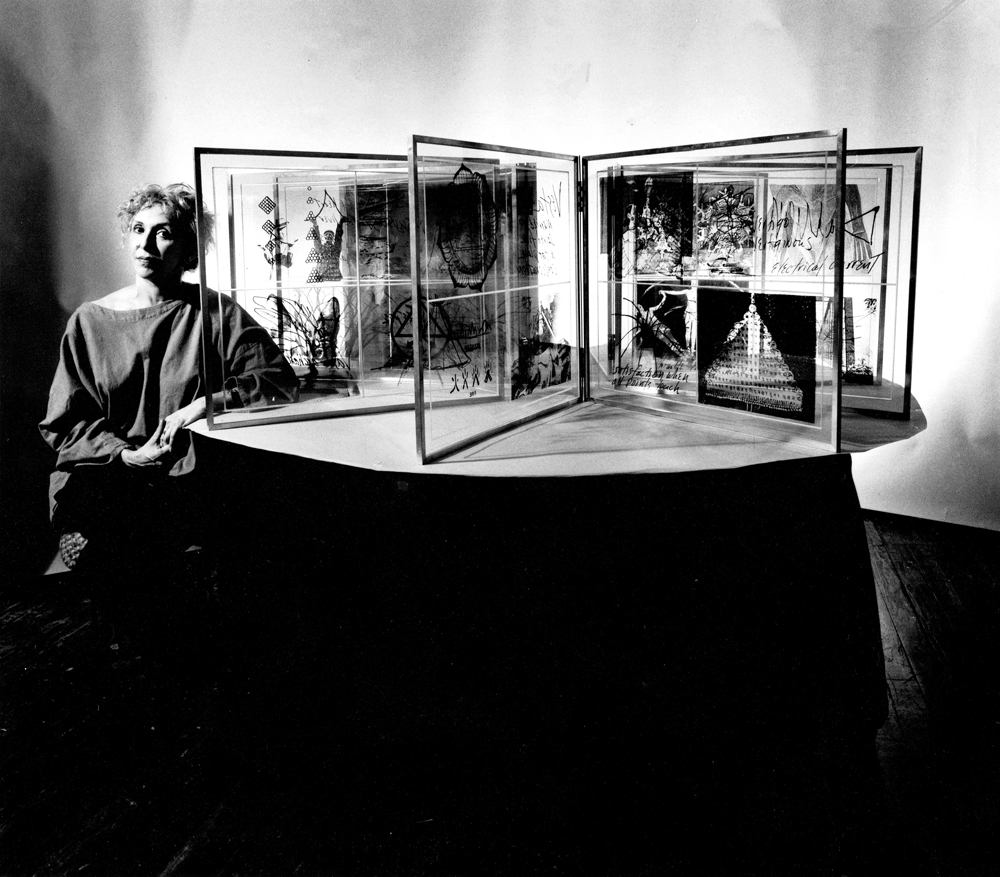

“Carolee Schneemann: Further Evidence. Exhibit B” at Lelong Gallery, New York. On view from October 21 to December 3, 2016, installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong.

L.P. - I find it peculiar that your work has sometimes been categorized as ‘masculine.’

C.S. - I was always struggling to escape the prejudice that my work resembled [Joseph] Cornell, or [Robert] Rauschenberg, and one of the reasons I began to motorize aspects in my painting constructions was because the men hadn’t done that.

L.P. - Can you tell me more about your work in relation to cancer research and your exhibition “Further Evidence: Exhibit A” at PPOW Gallery? I think there are several layers of specific research in your work that communicate a strong and important message to the spectator.

C.S. - I’m struggling with different principles in that work. One has to do with the medieval and archaic destruction of women healers, as they’re being turned by the patriarch and the church into witches, and their association then with the plague and with the very social dynamic that they used to cure. Once they’re attacked then they’re demonized. And I began to associate that with contemporary cancer treatment and its affiliation with warfare, the metaphor of fighting cancer. And you’re being treated with poison, radiation, amputation. And that is in juxtaposition to alternative healing traditions, which are nature-based and try to cleanse the system and build the immunity of the individual. That’s in our culture a relatively forbidden set of procedures, which are themselves demonized and forbidden so that alternative organic therapies are usually practiced outside of the country. And given that proportion of constraint, I went to an alternative therapy clinic in Mexico based on a very coherent theory of cancer treatment called Gerson Therapy. I did that and made a film of being in that humble little hospital and some of the procedures.

Carolee Schneemann, Dark Pond, 2001-2005, works on paper, 12 unique watercolor and crayon drawings with digital print layer, 54” x 56” (overall installation). Courtesy of the artist, P.P.O.W. and Galerie Lelong.

L.P. - You have had an important trajectory and have met many wonderful and creative minds who have been as fortunate to collaborate with you as you have been to collaborate with them-artists such as John Cage, Stan Brakhage, Paul Sharits, Hannah Wilke, Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg.

C.S. - Brakhage was Jim Tenney’s (my partner’s) best friend from Colorado, from high school. They were so close as being unique, special and probably weird in Denver high school. Jim did the first music for Brakhage’s earlier films, and he was a close intellectual companion to us until other things happened that tore into the friendship. But one of the things Brakhage believed was that to become an artist he had to go study with the artists he most admired. And he managed to live with them and impose himself because he was an aspiring young artist. Through Stan, Jim and I met Joseph Cornell, Maya Deren. Jim brought us to the works and friendships of John Cage, Carl Ruggles, Varese and other composers. I brought us to the realm of abstract expressionists and contemporary sculptors.

BREAKING THE FRAME

L.P. - Breaking the Frame is denoted as a kinetic, hyper-cinematic intervention, a critical meditation on the intimate correlations animating art and life. For me, personally, it’s an interesting and important documentary about women in the arts. How did you and the film’s director, Marielle Nitoslawska, meet?

C.S. - I was working in Montreal eight years ago-or seven years ago. I was teaching there and I found a wonderful studio where I could still be home here upstate and take the train from Rhinecliffe and in five or six hours be in Montreal and away from our government. It was a great relief just even for part of every month. I saw this woman at a film showing and said she is amazing and interesting and now that I’m here I’d like to meet her. And she had already used footage of mine in an early film of hers called Bad Girls. So we became very close friends and she wanted to make a portrait of my art and life, and she got a grant and was able to stay on top of our thoughts for six years. She came here to Springtown, and I’d go to her place in Montreal. She worked intensively for six years, during which time I never asked her how it was going. I had a complete trust in how it was going to be.

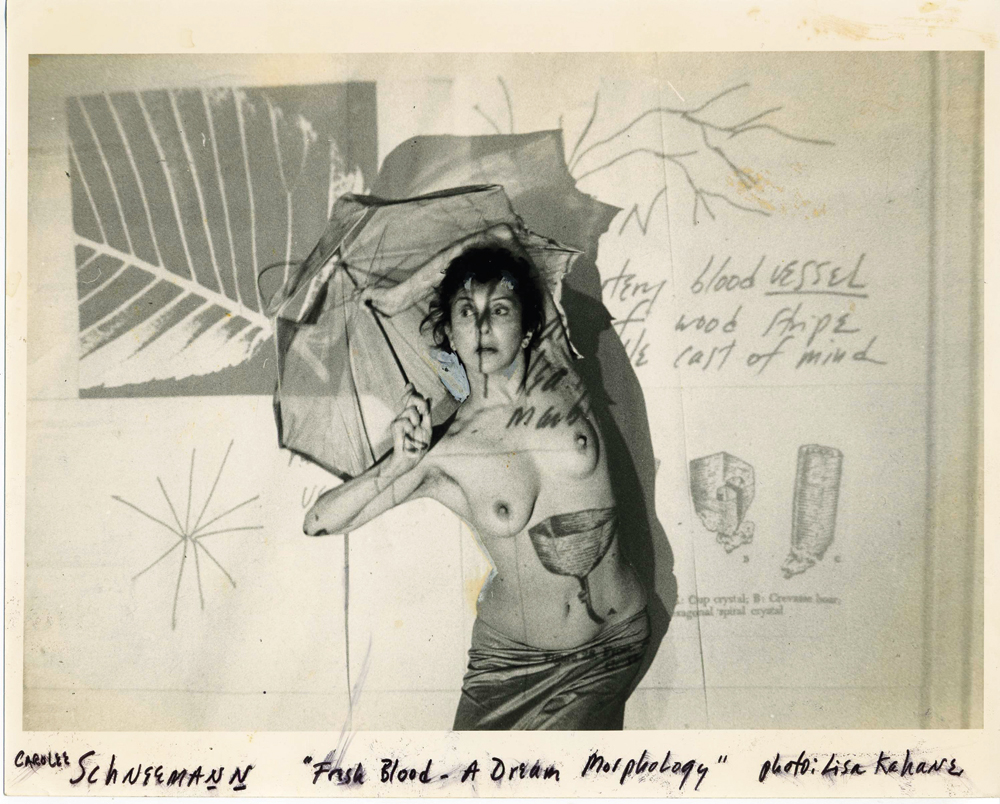

Carolee Schneemann, Fresh Blood: A Dream Morphology, 1983, video, 11 minutes, still. Courtesy of the artist and P.P.O.W.

L.P. - There are a lot of amazing things happening today with new technologies and new media, especially with a lot of women taking the primary positions in science and technology. You can really feel their presence in this sector. Do you have a message or any advice you would like to send to this generation of millennial women artists?

C.S. - The whole ecology and psychodynamic of our inheritance is in jeopardy. For most younger artists, I would love to propose that they go work for the Friends Service Committee. But it’s become extremely dangerous, and the fragility of it means it can’t be recommended-but it’s something I wish could still happen. And you know what that’s about. That’s going to warfare situations where people have no water; where they need construction, they need hospitals, they need materials, they need assistance in every basic way that has no publicity, no glamour, no commercial value except to be able to help, and of course you put yourself at risk.

L.P. - Thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Your art has been influential in many sectors and will continue to be a beacon for artists in the years to come. It saddens me to acknowledge the negative influence that fame and glamour has had on the creative influence today. Thanks to social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram, etc., Andy Warhol’s prediction about 15 minutes of fame seems to have come true. The race for glory is indeed damaging creativity in many ways, and I agree with your advice that helping other people should be a commitment that improves us by enriching ourselves and others’ lives.

Lara Pan is director of development and international programming at WhiteBox in New York. Some of the exhibitions she has recently curated include “Wim Delvoye: Torre” for the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (Venice, Italy), “Jean-Pierre Muller: 7×7” at WhiteBox, “Hans Breder: Mindscape - The Subtle Body” at Gleichapel (Paris), “Alessandro Brighetti” at Scaramouche (New York), as well as the group shows “The Wizard’s Chamber” at Kunsthalle Winterthur (Winterthur, Switzerland), “When The Fairy Tale Never Ends” at Ford Art Project (New York) and “Pandora’s Sound Box” at Performa (New York).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.