« Features

Interview with Warren Neidich

An American post-conceptual artist, writer and theorist, who splits his time between Los Angeles and Berlin, Warren Neidich has been exploring scientific and philosophical ideas in his art for the past 30 years. Widely published and exhibited Neidich works in a variety of media-from photography, video and painting to Internet downloads, noise installations and performance-to convey the process of the brain. The founder of the nomadic Saas Fee Summer Institute of Art, which has held classes in Switzerland, Germany and California, Neidich recently took time from his schedule of teaching at the Sorbonne University in Paris to discuss his ideas and how they are expressed in the works on view in his recent survey at Galerie Priska Pasquer in Cologne.

An American post-conceptual artist, writer and theorist, who splits his time between Los Angeles and Berlin, Warren Neidich has been exploring scientific and philosophical ideas in his art for the past 30 years. Widely published and exhibited Neidich works in a variety of media-from photography, video and painting to Internet downloads, noise installations and performance-to convey the process of the brain. The founder of the nomadic Saas Fee Summer Institute of Art, which has held classes in Switzerland, Germany and California, Neidich recently took time from his schedule of teaching at the Sorbonne University in Paris to discuss his ideas and how they are expressed in the works on view in his recent survey at Galerie Priska Pasquer in Cologne.

By Paul Laster

Paul Laster - What was the title of your recent show, “Neuromacht - Noise and the Possibility of a Future,” at Priska Pasquer meant to frame?

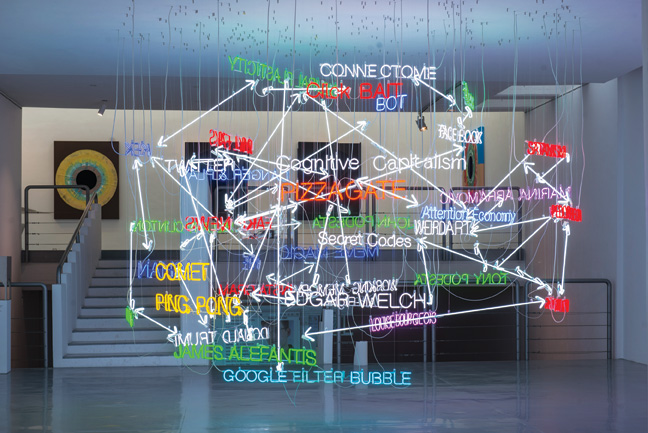

Warren Neidich - “Neuromacht - Noise and the Possibility of a Future” was a time-based exhibition in four acts that unveiled itself over the course of six months. The title resulted from the combination of the titles of my recent book of essays, published by Merve Verlag in Berlin, entitled Neuromacht, translated as Neuropower, and a symposium I organized in 2015 at the Goethe-Institute, Los Angeles entitled “Noise and the Possibility of a Future.” These two discursive interests, neuropower and noise, still continue to play important conceptual roles that direct my art practice. They provided the two bookends, if you will, for this exhibition. On one end, the large hanging neon sculpture Pizzagate, that filled the main hall of the first floor of the gallery, illustrated the events of the fake news story Pizzagate through the scrim of the new apparatuses at play of what has been named cognitive capitalism. In cognitive capitalism the brain and mind are the new factories of the 21st Century. Brain in this context refers to the material brain inside the skull, the empathic and sensorial body and the world consisting of networks of objects, things and the evolving socio-linguistic milieu. We no longer physically labor on assembly lines, as we did in industrial capitalism, but rather we use mental labor to complete on-line virtual templates on Booking.com and Travelocity.com, or search topics of interest on Google.com-all the time producing data in its wake. Data that is not simply passive, acting as a register of our likes and dislikes, but is active, directing and coopting algorithmic and bots to intercept us in our daily web searches, leading us astray and dangling in the non-knowledge of our own self contained Google Search Bubbles. Neuropower is an essential component of cognitive capitalism and subsumes the biopower of industrial capitalism. It redirects the actions of power from the body to the brain in its attempt to normalize difference and sculpt a homogenous population of thinkers.

Warren Neidich, Scoring the Tweets, 2018. All the images are courtesy of the artist and PRISKA PASQUER, Cologne.

At the opposite end were my sculptural and performative works centered around noise as a form of resistance. Distributed around the gallery were three works made from destroying vintage speakers in my studio with tools usually used for the opposite reason-that of making works. I was inspired by Robert Morris’s seminal work Box and the sound of its own making, 1961, as well as Gustav Metzger’s Auto-Destructive Art, in which art contains within its own making the means of its own destruction.

P.L. - Was the show a survey or a culmination of related ideas?

W.N. - In a way it was both. The exhibition provided an opportunity to display what had been displayed piece meal in other venues, such as the Kunstverein Rosa-Luxemberg Platy, all together. It also provided a forum for the presentation of research I have been doing since 2009, when I first discovered and published the work of economist Yann-Moulier Boutang and philosophers Maurizio Lazzarato and Paolo Virno.

P.L. - One of the largest and most complex pieces in the show is the hanging, 2017 neon light sculpture Pizzagate, which diagrammatically connects elements of the 2016 American presidential election to cultural and technological realms. What are you constructing or relaying in this artwork?

W.N. - Pizzagate, for those who may not be familiar with the term or have forgotten it, describes a now debunked conspiracy theory that went viral at the end of the 2016 presidential election. It asserted that Hillary Clinton and some of her top aids were part of an international child sex ring run out of the Clinton Foundation and located in the basement of the Comet Ping Pong pizza parlor. The alleged proof of these accusations came from the illegal hacking of Clinton’s campaign manager, John Podesta’s, personal emails publicly displayed on WikiLeaks, and through trawling the Instagram account of James Alefantis, searching for sexually lewd and explicit images. The Pizzagate neon was an interpretive hanging sculpture in the shape of the iCloud, a cloud storage and computing service provided by Apple, which instantiated the interconnected and immaterial relations of the Internet and illustrated the Pizzagate fake news story, as well as its back and related side stories, such as the loop involving art collector Tony Podesta, artist Marina Abramović and her performance Spirit Cooking. It also displayed a glossary of terms like 4-Chan, Danger and Play, Instagram and KEK, which drew attention to the new media outlets that intensify the resonances of distributed false news along Internet channels. Finally, it highlighted the capacity of engineered virtual environments to react and sculpt the neural plastic brain. In cognitive capitalism, media outlets are being used by the alt-right to spread their lies, like Pizzagate, and were important for the election of right wing candidates like Donald Trump.

P.L. - The size and shape of the cloud-like structure, color of the individual words and phrases and diagrammatic arrows make it a highly attention-seeking and attention-getting piece. Is the attention that we pay to words and memories the underlying subject?

W.N. - As you note the shape of the sculpture is cloud-like and as stated above is a loose illustration of Apples’ iCloud, but is also meant to represent what is referred to as the connectome, which is the data set describing the connection matrix of the brain and nervous system. It represents the network of anatomical connections linking neural elements and is now used by neuroscientist to represent the material brain. The diagrammatic morphology is, on the one hand, nostalgic for a history of two-dimensional graphic structures used by artists all throughout modernism. From Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass (1915-1923) and the blackboard drawings of Joseph Beuys in his Das Kapital Raum installation (1970-1977) to Mark Lombardi’s Global Networks of the early 1990s and more recently in the work of Julie Mehretu’s Mural (2010) at Goldmans Sachs and Jorinde Voight’s Territorium (2010.) Since the late 1990s I also worked with diagrams in such works as my wall drawing Political Art in the Sixties was about Delineation, Political Art Today is about Differentiation, first exhibited at IASPIS in Stockholm, 2008 and then again in 2009 at the Drawing Center, NYC in an exhibition entitled FAX curated by Joao Ribas. In 2014 I made my first neon diagram, The Duende Diagram, exhibited at the Freiraum Quartier 21, Vienna, Austria.

You are correct in proposing that my attraction to neon had to do with its attention grabbing quality and its purpose in my sculpture to highlight this attention. Neon lights flashing at night played an undeniably important role in attracting the attention of potential buyers speeding their way home along the suburban boulevard. Today the importance of the virtual venue has subsumed that of real one and on-line shopping is becoming more and more important. The Internet is a place of image abundance and therefore requires a way to allocate attention efficiently. According to an economist like Thomas Davenport, we are living in an attention economy, in which attention becomes a more important currency than money. Such apparatuses like clickbait are utilized to attract user performance and have been deployed by Internet advertisers and the alt-right to spread their agendas! The subject-now referred to as the cognitariat-clicks on sensational, exaggerated, and eye-catching headlines like the Pizzagate story. I am taking this argument one step further by including neural plasticity and epigenesis into the mix. Neural plasticity refers to the ability of the material brain to change and epigenesis, which-according the neurobiologist Jean Pierre Changeux-describes the process through which the environment causes these changes through a process of selective stabilization of the reactive synapses. Long-term memory is one such example of this stabilization process. As such, in cognitive capitalism the customized Internet customer is produced in a very different way than in post-Fordism and the event economy, in which needs and desires were produced in real time contiguous with the decision to make the purchase. In the valorized market of ideas, which constitutes cognitive capitalism, the actual production process is completed in the mind’s eye. Additional value is created through the cognitive laboring of the cognitariat and furthermore becomes constituted in the biomorphic changes occurring at the neural synaptic junction, where it is archived for future encounters. Additionally, the sculpting of the brain is a key component of the process of neural optimization geared to a simulated virtual shopping environment.

P.L. - One the phrases in the piece, “Cognitive Capitalism,” seems to be at the heart of much of your recent work? What does it mean and how are you employing the concept?

W.N. - Cognitive capitalism is divided into an early and late stage. The description of the early stage is a result of the work of a group of Italian Political philosophers who realized early the effect that the then-burgeoning new economy would have on labor and work. They came together under the rubric Post-Workerism (Post-Operaismo) and stressed the importance of immaterial labor to the production of subjectivity and the end of the law of value. There are five components to its definition, which those who attended the Venice Biennale or Documenta 14 might recognize: precarity, real subsumption (which refers to the expansion of the workspace to include our complete lives,) the importance of immaterial labor, financialization and valorization. The late stage of cognitive capitalism understands the importance of the material brain as the site and focus of the new economy in our century of the brain. If the brain and mind are in fact the new factories of the 21st Century, then it behooves capitalism to commoditize and optimize this machinery as they did the working body in the 19th century. Late cognitive capitalism is described by three characteristics. Neuropower, in which populations of brains are acted upon through the agency of its neural plastic potential in order to change and transform its architecture in an effort to normalize, synchronize and commodify it, is the first and most important characteristic. Hebbinism-named after the Canadian neurobiologist, D.O. Hebb, and a word that I invented-is the second principle. It concerns the transition of the regulation and optimization of the body of the proletariat in Fordism and Taylorism to the regulation and optimization of individual and populations of brains in populations of cognitariats. Key here is the concerted action to regulate the combined action of billions of neural synaptic junctions. Thirdly, the increased importance of the functions of frontal lobe of the brain like attention, prediction and working memory in the new economy.

Warren Neidich, Neuromacht - Noise and the Possibility of a Future, installation view at PRISKA PASQUER, Cologne.

P.L. - How do the two redacted newspapers from The Washington Post, which are presented in the top of an archival storage box like On Kawara’s Date Paintings, relate or interact you’re your Pizzagate light sculpture?

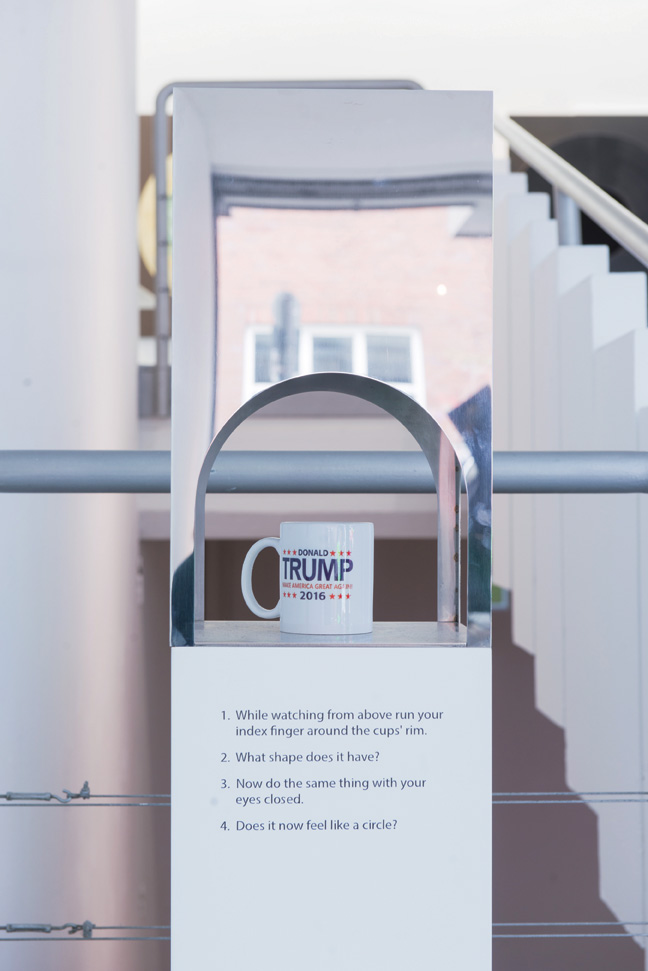

W.N. - The two redacted newspaper works that hung on the south wall of the gallery do in fact speak to On Kawara´s series of date paintings, but they also relate to Jenny Holzer’s more recent Redacted Painting series. They are markers of a moment in time, but they also constitute a form of media on the way out. Like other victims of the information and knowledge economy, newspapers are becoming extinct or at least are in the final stage of a terminal disease. The punk nature of Holzer’s works constitutes a form of violence and disembodiment of the word. My work is related to On Kawara’s in the sense of removing the clutter and excess that is not required for the reading of the work. It blackens all the words that are not directly about James Welch’s relation to the Pizzagate scandal. It directs the gaze of the viewer only towards the essential information. As such, my works The Trump Cup, situated on the opposite end of the gallery, and the Washington Post pieces (Arrest in shooting at D.C. “pizzagate” restaurant and Deluded into a D.C. „hero mission”?) concern various forms of optical manipulation. In the case of the Trump Cup, there’s a kind of visual distortion, while in the case of the Washington Post pieces (both 2017,) it’s a desire for more clarity and perspective. The works resonate together across a pathway that cuts through the hanging Pizzagate neon sculpture.

P.L. - The 2018 installation work Scoring the Tweet(s) also uses language from found sources. Whose words are they and how are you making new use of them?

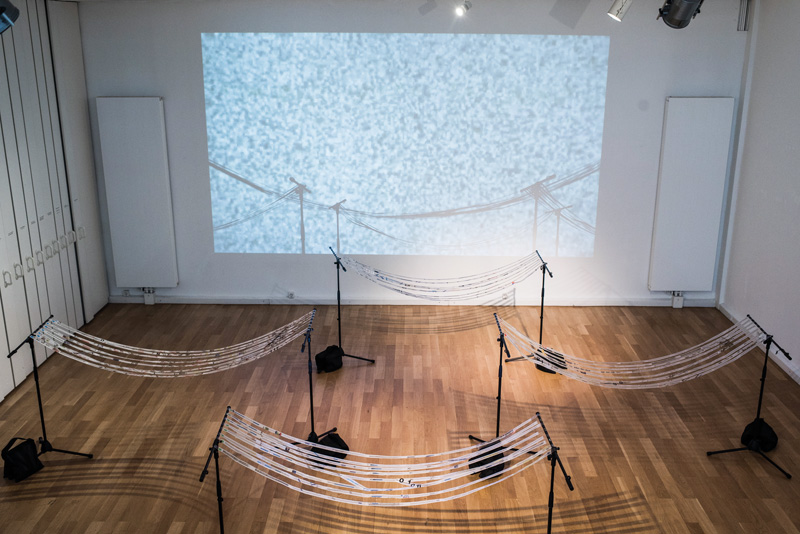

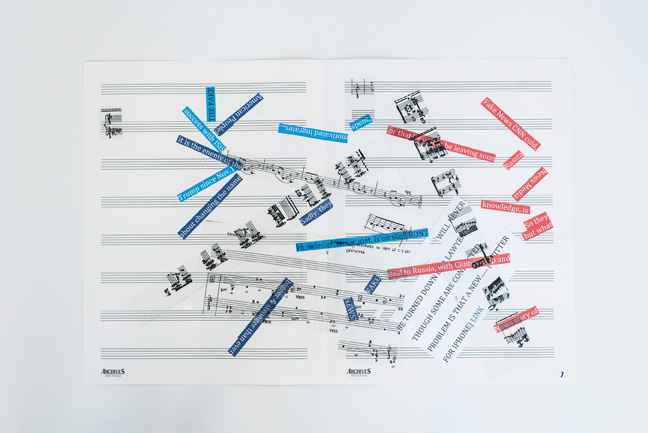

W.N. - Scoring the Tweet(s) (2018) is my most recent work using graphic scores. It follows such works as How do you translate a text that is not a text? How do you perform a score that is not a score? (2013,) performed at Townhouse Gallery in Cairo, and NSA/USA: Sound as Prophesy (2013,) which premiered at New York’s Emily Harvey Foundation in 2013 and followed as part of the parallel programs, Manifesta 10 at the Experimental Sound Gallery, Pushkinskaya Art Center, St. Petersberg, Russia in 2014.

Scoring the Tweet(s) took place in the lower atrium of the Priska Pasquer Gallery as part of the second phase shift of the exhibition we mentioned before “Neuromacht- Noise and the Possibility of a Future.” The work consisted of 193 tweets made by Donald Trump since his election, in which the word ‘Fake News’ was used. These were cut up and reassembled in a random manner-first as poems and then as scores on composition paper in the manner invented by Brian Gysin and William Burroughs. In many ways this work pays tribute to the work of Earle Brown, John Cage and Morton Feldman, except that their context necessitated other approaches to the avant-garde processes they engaged with, which are quite different from those we have today. Today the power of graphic scores and improvisation is more akin to the sound works of Miles Davis and are connected to what Eero Tarasti called a cultural semiotic, in which a unique sense of the possible is created.

It is this cultural semiotic that my works attempted to create through a series of transformations and translations that the musicians and I engaged with, in which through invented methods, materials and dispositifs (specific to our artistic practices) we were able to estrange and deconstruct the meanings of the Trump tweets. We were able to speak to power by delinking the meanings of the words and phrases and reprocessing them through the artistic voice-this time through performative gestures. As such, what resulted was an alternative visual and acoustic distribution of sensibility, which rather then policing, normalizing and homogenizing a collectivity, as Jacques Rancière in his Politics and Aesthetics has espoused, it instead emancipated it by releasing the heterogeneity of the multitude.

P.L. - Who were the musician that performed the work and how did you instruct them to interpret the score?

W.N. - Through word of mouth, and relying on musicians I had used in previous works, I was able to assemble this group of artists in Cologne. The final result of my artistic labor was an installation of four scores, each two meters by one meter. The scores were suspended between two music stands. Each score contained six staffs, which were individually suspended on the back surface of one-inch-wide transparent acid-free Scotch tape, so that they could be easily read. The scores were given the maximum of possible space and oriented in such a manner as to allow the musicians 360-degree free access to them.

My approach at the rehearsal was to first have them study the scores and then play and interpret them as they would like. I gave them no formal instructions and reminded them that they could perform them left to right, right to left, from up to down or down to up. What is important is that I choreographed their entrances and departures from the stage, as well as which score they would perform at any time, acting more like a conductor. For this purpose, I made a schedule with the two-hour performance divided into ten-minute sections. Each artist was then assigned a specific section and stationed at a particular score. Sometimes that meant playing solo and sometimes that meant playing together with one or many of the other musicians. They were advised to keep their eyes on me when they could. Sometimes I reacted to the emotional and affective dynamics of the production and went off script, which meant changing the schedule.

P.L. - How is the noise that the musicians created during the performance related to the visual and verbal noise that you gathered from the media and your memory for the piece?

W.N. - That is a fascinating question because I think it gets to the bottom of how works of art, and especially improvisation, are premeditated or not. A work of art can be premeditated and appear finished in your mind’s eye. The idea is through a series of moves and gestures that internal image is approached step by step by the work in progress. Each move brings you closer to your preconceived image of the work. On the other hand, a work can commence without a set image and operate as a work in process. The artist stops the process at a particular moment when the work comes together for him or her as a work. A third condition emerges when an artist has a preconceived notion of the work, but is flexible enough to allow for another idea to take its place-one that unfolds in the process of its making. In my case I usually follow the third condition.

P.L. - You also exhibited two sculptural works from 2014, The Infinite Replay of One’s Own Self Destruction, #1 and #2, which consists of broken speakers that emit a cacophony of noise. Are you using destruction like the abstract and conceptual artists of the past used reduction to reveal how chance and risk are being removed by digital algorithms?

W.N. - Although chance and risk are important considerations in this work they are subsumed by my interest in Auto-Destructive Art and noise. Algorithms are an essential element of the knowledge economy, Big Data, consumer neuroscience and cognitive capitalism. They have the capacity to foretell the future and-as we know-there is tremendous value in online trading, where zero risk is the goal for maximizing profit. They can even foresee who will create criminal activity and who will not, which makes them a threat to free choice. My work is related to a theory of noise, as it results from the process of Auto-Destructive Art. As I mentioned, these works derive from performances I achieved alone in the studio, where I recorded actions directed towards destroying vintage speakers-the kind of speakers that I listened to as a teenager. These speakers were then reconstructed and then reassembled together inside a plinth, which had first been cut into to provide a support system to hold the speakers tight in place. For instance, three speakers were held by a single black hollow plinth, which also acted as a woofer to amplify the base component of the recording.

P.L. - Another dominant part of the show was the selection of your Wrong Rainbow Paintings (2012-14,) which abstract historical landscape paintings where the artists-including Maurice Prendergast, Frederic Edwin Church and Caspar David Friedrich-purposefully misrepresented the colors of the rainbow. What was the process for making these canvases and how do they fit into the development of your conceptual platform?

W.N. - My general approach is conceptual, but I am a wet conceptual artist not a dry conceptual artist. I do not drain the work of all its pleasure, but rather use its pleasure to create doorways of understanding and appreciation of its conceptual framework. The Wrong Rainbow Paintings developed out of a research in color. I stumbled rather clumsily on the fact that in landscape painting, especially during the 19th Century, the color of rainbows in landscape painting was oftentimes wrong. Either the palette of the bow was off or the order of its colors were askew.

The Wrong Rainbow Paintings emerged out my analysis of this phenomena, which by the way was characteristic of rainbows painted in the 20th Century, as well. This color problem was more radiant in American landscape, especially paintings of Western Landscapes. My first paintings began in Europe and I therefore began to analyze European works. Peter Paul Rubens’ Landscape with Rainbow (1636) shows a rainbow of predominately yellow and blue, while in John Constable’s painting Landscape with Double Rainbow (1812) the second bow is painted in the same manner as the first and the order of the colors are the same. Interestingly in a second rainbow the colors should be reversed, as in the case of John Everett Millais painting The Blind Girl (1856.) The story goes that the same mistake was made until it was pointed out to him when he exhibited the painting. The painting now has the bows reversed. Alfred Bierstadt’s Rainbow Over Jenny Lake and Four Rainbows over Niagara Falls are extreme examples of this phenomena of wrongly painted rainbows, where artistic inspiration overwhelms scientific truth.

This work began as a series of acrylic paintings on Fabriano roll paper. The colors were first mixed to match the original rainbows hues as found in the painting printed in a book. These colors were laid down thickly with acrylic paint on the paper and then a horsehair brush of various dimensions, made by people with disabilities, was dragged through the paint and carried down the paper in one continuous stroke, exhibiting the colors as well as creating a negative on the brush used. Both were exhibited.

Later I made a series of works where the paper was substituted with raw canvas. The recent work that was shown in the gallery connected the halo of Buddha to the Rainbow and the work was made with a specialized rotary apparatus that created a circular arc. A middle circle of varied dimension was then cut exposing a black velvet under-canvas. The work then came to resemble an eye with a black pupil, in a variety of sizes, staring back at the audience. The varied pupils were a metaphor for the painting coming alive, as well as the pathological condition of anisocoria, in which the pupils of each eye are of different sizes. This was a pathologic condition that characterized the eyes of David Bowie, who–as a result of injury–had two pupils of different sizes.

P.L. - Photography is a medium that you’ve explored over the course of your career and you exhibited two series, which were begun in 1997, in the show. Blanqui’s Cosmology (1997-2007) deals with portraiture, performance and light’s role in photography while Double Vision - Louse Point (1997-2000) juxtaposes red and green lens used in optometry tests with landscape views of the famous meeting point for the abstract expressionists in East Hampton, New York. Why did you decide to show these two bodies of work in this context?

W.N. - In many ways these two works represent the very foundation of the exhibition, as well as a turning point in my career. As you might remember, my works before 1995, like American History Reinvented (1985-1991), concerned issues of performance, reenactment, revisionist histories, the archive and fictional documentary entangled with a deep interest in the materiality of photography. In 1996 I decided that I would revisit my training in neurobiology and ophthalmology to create a new body of work which was reflective of that specialized knowledge. This began my work in neuroaesthetics. The two bodies of work that you asked about are reflective of this sphere of knowledge.

First a definition. Neuroaesthetics, as I mentioned before is a field of research I invented back in 1996. It aims to investigate the same spheres of knowledge as cognitive neuroscience, but instead uses the apparatuses, histories and materials of artistic research to produce an alternative paradigm, consisting of different facts and explanations of shared phenomena like memory, sensation, perception, the meaning of color and abstraction. Importantly I see Neuroaesthetics as an activist political tool important for social and political transformation. Neuroaesthetics, adapts the ideas of continental philosophy-especially those of Gilles Deleuze-to understand that creating new circuits in art means creating them concomitantly in the material brain, as well. In opposition to the power of institutionally designed environment to normalize–what Jacques Rancière calls the distribution of the sensible, to produce a compliant people–Neureoaesthetics calls for an estrangement of this environment with neural material consequences. By estranging the conditions of the distribution of the cultural habitus, as it folds into these distributions of the sensible, you change the conditions through which the brain’s hardware, neurons, dendrites and synapses and its software, functional resonances sculpted in the end, affecting the conditions for thought and theory of mind. The history of art is a reaction to this history of various socio-political-cultural transformations, that it materializes in various forms with consequences for the brain and mind, with which they are linked.

Double Vision, Louse Point and Blanquis Cosmology are Neuroaesthetic works. In Double Vision Louse Point, I superimpose what are referred to as Red-Green Lancaster Glasses, used in the diagnosis of lazy eye, over photographic and video camera lenses to create the works you witnessed. I call them Hybrid Dialectics because they represent a hybrid state that entangles art and science without rendering either obsolete. However, the optical aberration that appears in each image and appears as misty circles or diffracted abnormality or peculiarity in the image is an indication of the lack of commensurability of the two systems. In the case of Blanquis Cosmology, five-second to five-minute light performances were managed in the dark in front of a camera lens maximally opened, which in isolation witnesses the action. All the subjects were bald men and woman, though mostly men. The penlight used for drawing is reflected as light bouncing off their heads and was registered on the Polaroid film as a series of light drawings and printed. This total work, which is comprised of over 1200 pictures, concerned an instantiation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Übermensch at the turn of the 20th century. The entire series acts as a typology of heads and visits such themes as the monstrosity of Romanticism, the beginning of X-Ray technology as well as astronomic photography, spirit photography, physical anthropology and Occultism. In the pictures in the gallery we chose those works that mimicked what appeared to be the electrical discharges used by the brain in the transmission of information sometimes referred to as the oscillations and brain waves. The importance of these works for the show is that they form the foundation in which to understand the Pizzagate neon. The Pizzagate neon focuses on the new apparatus on the knowledge economy like clickbait, Meme Magic, the Google Bubble and the algorithms that drive the mind, as well as administering the brain. This new work is an extension of these early experiments in photographic and neuro-ophthalmologic apparatic binding.

P.L. - And not to leave a medium unturned, you resurrected your 2015 video The Search Drive, which begins with a Google search for spyware and the deep web and ends up connecting to website and Facebook page, for the exhibition. Is this video and your recently completed Pizzagate video, which mixes American politics with Marina Abramović performances, meant to be a mashup between data and Dada?

W.N. - The Search Drive and Pizzagate are videos using the archive of the Internet for source material. In both cases these works move the discussion of our generations infatuation with media as our new reality, in for instance the works of Richard Prince, to a discussion of the importance of the virtual as the space and place where our reality is taking place and performed. Artists of the Post-Internet generation are also focused on this reality. The Search Drive concerns the new composition of surveillance, while the Pizzagate video, which is actually titled Pizzagate: How Rumor becomes Delusion, tries to understand the circumstances of Edgar Madison Welch’s turn to temporary madness. It concerns how rumor becomes delusional in a valorized and financialized social economy, where new psychopathologic forces are at play.

Paul Laster is a writer, editor, independent curator, artist and lecturer. He is a New York desk editor at ArtAsiaPacific and a contributing editor at Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art and artBahrain. He is also a contributing writer to ARTPULSE, Time Out New York, Observer, Modern Painters, Cultured Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar Arabia, Galerie Magazine and Conceptual Fine Arts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.